Communicable Diseases

Original Editor - Naomi O'Reilly

Top Contributors - Naomi O'Reilly, Lucinda hampton, Kim Jackson, Tony Lowe, Admin, Vidya Acharya, Jess Bell, Khloud Shreif, Olajumoke Ogunleye, Niha Mulla, 127.0.0.1, Laura Ritchie, Oyemi Sillo, Tarina van der Stockt and WikiSysop

Introduction[edit | edit source]

According to the World Health Organisation “over 13 million people die each year from infectious and Parasitic Diseases: One in two deaths in some developing countries. Poor people, women, children, and the elderly are the most vulnerable. Infectious diseases continue to be the world’s leading killer of young adults and children” [1].

Socioeconomic, environmental and behavioural factors, as well as international travel and migration, foster and increase the spread of Communicable Diseases. Vaccine-preventable, foodborne, zoonotic, health care-related and communicable diseases pose significant threats to human health and may sometimes threaten international health security [2].

According to Lindahl and Grace (2015), communicable diseases have had civilisation-altering consequences throughout history. An estimated 50–100 million humans worldwide succumbed to infection during the Spanish Flu Pandemic in 1918–1920 while rinderpest was in part responsible for death by starvation of almost two-thirds of the East African Massai population after it caused massive death to livestock. [3]

As a result of better living conditions, increased access to health care including better vaccines, advent of antibiotics and improved surveillance and monitoring in relation to public health, the proportion of infectious diseases was trending downwards during the early Twentieth Century. However, an increase in the emergence and re-emergence of infectious diseases became evident in many parts of the world towards the later part of the Twentieth Century. [3] [4]

Weiss & McMichael (2015)[4] highlight that over 30 new, emerging diseases have been identified, including COVID 19, Legionnaires' Disease, Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV) / Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndrome (AIDS), Hepatitis C, Bovine Spongiform Encephalopathy (BSE) / Variant Creutzfeldt-Jakob Disease (vCJD), several Viral Hemorrhagic Fevers and, most recently, Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome (SARS), Avian Influenza, Ebola and Zika Virus. The authors in part relate the emergence of these diseases and the resurgence of old ones such as Tuberculosis and Cholera to various changes in human ecology including;

- rural-to-urban migration resulting in high-density peri-urban slums

- increasing long-distance mobility and trade

- the social disruption of war and conflict

- changes in personal behavior

- human-induced global changes, including widespread forest clearance and climate change. [4]

What are Communicable Diseases[edit | edit source]

Communicable diseases are those that are spread from one person to another through a variety of methods. Socioeconomic, environmental and behavioural factors, as well as international travel and migration, foster and increase the spread of Communicable Diseases. Vaccine-preventable, foodborne, zoonotic, healthcare-related and communicable diseases pose significant threats to human health and may sometimes threaten international health security. How these diseases spread depends on the specific pathogen or infectious agent and means of transmission: [5]

Pathogens[edit | edit source]

Bacteria[edit | edit source]

- These one-cell organisms are responsible for illnesses such as strep throat, urinary tract infections and tuberculosis. Bacteria constitute approximately 38% of human pathogens and 30% of the emerging pathogens in humans. [3] [6]

Viruses[edit | edit source]

- Even smaller than bacteria, viruses cause a multitude of diseases. According to Lindahl & Grace (2015), it is estimated that 44% of the diseases considered emerging in humans are viral. Emerging Infectious Diseases that have received most publicity in the past 30 - 40 years have been viruses. Notable examples have been Corona virus 19, HIV, SARS, and Ebola. [3] [6]

Fungi[edit | edit source]

- Many skin diseases, such as ringworm and athlete's foot, are caused by fungi. Other types of fungi can infect your lungs or nervous system. [6] [3]

Parasites[edit | edit source]

- According to the CDC, a parasite is an organism that lives on or in a host and gets its food from or at the expense of its host. Malaria is caused by a tiny parasite that is transmitted by a mosquito bite. Other parasites may be transmitted to humans from animal feces. [6] [3] [7]

Prions[edit | edit source]

- A prion is an infectious agent composed entirely of protein material, called PrP (short for prion protein), that can fold in multiple, structurally-distinct ways, at least one of which is transmissible to other prion proteins, leading to disease that is similar to viral infection. Bovine Spongiform Encephalopathy (BSE), also known as Mad Cow Disease, is a progressive neurological disorder of cattle that results from infection by an unusual transmissible agent called a prion. [3]

Transmission[edit | edit source]

Defining the means of transmission of a pathogen is important in understanding its biology and in addressing the disease it causes. Infectious organisms may be transmitted either by direct or indirect contact. Direct contact occurs when an individual comes into contact with the reservoir. Indirect contact occurs when the organism is able to withstand the harsh environment outside the host for long periods of time and still remains infective when specific opportunity arises.

Direct Contact[edit | edit source]

Person to Person:

- Physical Contact with an infected person, such as through Touch (e.g. Staphylococcus), Sexual Intercourse (e.g. Gonorrhea, HIV), Fecal/Oral Transmission (Hepatitis A), or Droplets (Influenza, Tuberculosis)

Animal to Person:

- Bites from infected insects or animals capable of transmitting disease (e.g. Mosquito: Malaria, Zika Virus and Yellow Fever; Flea: Plague; Tick: Lyme Disease); and handling of animal waste (e.g. Toxoplasmosis)

Mother to Unborn Child:

- Infectious Disease may be transmitted to the unborn child through the placenta or during passage through the vaginal canal during the birth process e.g. HIV, Hepatitis, Herpes and Cytomegalovirus.

Indirect Contact[edit | edit source]

- Contact with a contaminated surface or object (Norovirus), Food (Salmonella, E. Coli), Blood (HIV, Hepatitis B) or Water (Cholera)

- Travel through the air (e.g. Tuberculosis or Measles)

Defense Mechanisms[edit | edit source]

The immune system has evolved to protect us from a host of infections.

Host defenses that protect against infection include:

Natural Barriers (e.g. Skin, Mucous Membranes) [8][edit | edit source]

- Skin usually prevents invading microorganisms unless it is physically disrupted or broken (e.g. by Injury, IV Catheter, or Surgical Incision). Exceptions include the following:

- Mucous Membranes contain mucous membranes that produce secretions that have antimicrobial properties (e.g. cervical mucus, prostatic fluid and tears containing lysozyme). Local secretions also contain immunoglobulins, principally IgG and secretory IgA, which prevent microorganisms from attaching to host cells.

- Respiratory Tract has upper airway filters which transport invading organisms away from the lung by the mucociliary epithelium. Coughing also helps remove organisms. If the organisms reach the alveoli, alveolar macrophages and tissue histiocytes engulf them. However, these defenses can be overcome by large numbers of organisms or by compromised effectiveness resulting from air pollutants (e.g. cigarette smoke) or interference with protective mechanisms (e.g. endotracheal intubation, tracheostomy).

- GI Tract barriers include the acid pH of the stomach and the antibacterial activity of pancreatic enzymes, bile and intestinal secretions. Peristalsis also removes microorganisms and if delayed, can result in prolonged infection. Compromised GI defense mechanisms may predispose patients to particular infections (e.g. achlorhydria predisposes to salmonellosis). Normal bowel flora can inhibit pathogens; alteration of this flora with antibiotics can allow overgrowth of inherently pathogenic microorganisms (e.g. Salmonella Typhimurium) or superinfection with ordinarily commensal organisms (e.g. Candida albicans).

Nonspecific Immune Responses (e.g. Phagocytic Cells [Neutrophils, Macrophages] and their products) [8][edit | edit source]

- Cytokines, produced principally by macrophages and activated lymphocytes, mediate an acute-phase response that develops regardless of the inciting microorganism. The response involves fever and increased production of neutrophils by the bone marrow.

- Inflammatory response directs immune system components to injury or infection sites and is manifested by the increased blood supply and vascular permeability, which allows chemotactic peptides, neutrophils, and mononuclear cells to leave the intravascular compartment.

- Phagocytes, which are drawn to microbes via chemotaxis, limit microbial spread through engulfment of microorganisms. Oxidative products such as hydrogen peroxide are generated by the phagocytes and kill ingested microbes.

Specific Immune Responses (e.g. Antibodies, Lymphocytes) [8][edit | edit source]

- The host can produce a variety of antibodies that bind to specific microbial antigenic targets. Antibodies can help eradicate the infecting organism by attracting the host’s WBCs and activating the complement system, which destroys cell walls of infecting organisms.

- Antibodies can also promote the deposition of substances known as opsonins on the surface of microorganisms, which helps promote phagocytosis.

Antimicrobial Resistance[edit | edit source]

Antimicrobial resistance (AMR) threatens the effective prevention and treatment of an ever-increasing range of infections caused by bacteria, parasites, viruses and fungi and, according to the WHO, is an increasingly serious threat to the global public health that requires action across all government sectors and society. Without effective antibiotics, the success of major surgery and cancer chemotherapy would be compromised. [9]

Antimicrobial resistance happens when microorganisms (such as bacteria, fungi, viruses, and parasites) change when they are exposed to antimicrobial drugs (such as antibiotics, antifungals, antivirals, antimalarials, and anthelmintics). Microorganisms that develop antimicrobial resistance are sometimes referred to as “superbugs”. As a result, the medicines become ineffective and infections persist in the body, increasing the risk of spread to others. [9]

While antimicrobial resistance occurs naturally over time, usually as a result of genetic changes, misuse, and overuse of antimicrobials both humans and animals, is accelerating this process. Examples of misuse include when they are taken by people with viral infections like colds and flu, and when they are given as growth promoters in animals and fish. [9]

Refresh your knowledge of some common communicable diseases:

Review your knowledge of Antibiotic Resistant Infectious Diseases which are frequent within the Hospital Setting

You can also check out our Communicable Disease Category which provides information on many other common and not so common Infectious Conditions:

Risk Factors[edit | edit source]

According to Boundless (2016), the spread and severity of the infectious disease is influenced by many predisposing factors. Some of these are more general and apply to many infectious agents, while others are disease specific. Some predisposing factors of contracting infectious diseases can be anatomical, genetic, general and disease-specific. Climate and weather, and other environmental factors that are affected by them, can also predispose people to infectious agents. Other factors such as overall health, age, and diet are also important considerations in the prevention of spreading infectious diseases[10].

Modifiable Risk Factors [edit | edit source]

Refer to characteristics that individuals or societies can change to reduce the risk of infectious disease and improve health outcomes. This includes Hygiene including water and sanitation, Vaccinations, Malnutrition, Food Preparation Methods, and Overcrowding.

Overcrowding [edit | edit source]

- High Population Density provides greater opportunity for contact between infectious diseases and susceptible people which leads to higher transmission rates.

- Large Concentration of Population once an epidemic starts, it spreads faster which leads to higher transmission rates.

- According to the WHO, from a purely epidemiological perspective, the provision of sufficient residential space and avoiding overcrowding are high-impact public health interventions to reduce the rate of transmission of communicable disease.

- The transmission of the infection can be avoided by staying away from affected people i.e. by practicing social distancing.

Types of Diseases:

- Airborne Droplet Diseases e.g. Measles, Meningitis, Acute Respiratory Infections, and Tuberculosis.

- Faecal-Oral Diseases e.g. Diarrhoea Diseases including Shigella and Cholera

Malnutrition[edit | edit source]

- Malnutrition leads to lower natural immunity, which often results in increased risk of infectious disease and increased progression of disease. Nutritional Crises can Precipitate Epidemics as lower immunity often means lower vaccine efficacy, and therefore a higher susceptibility for transmission

- Globally, the severe malnutrition common in parts of the developing world causes a large increase in the risk of developing active tuberculosis and other opportunistic infections, due to its damaging effects on the immune system. Along with overcrowding, poor nutrition may contribute to the strong link observed between tuberculosis and poverty. [10]

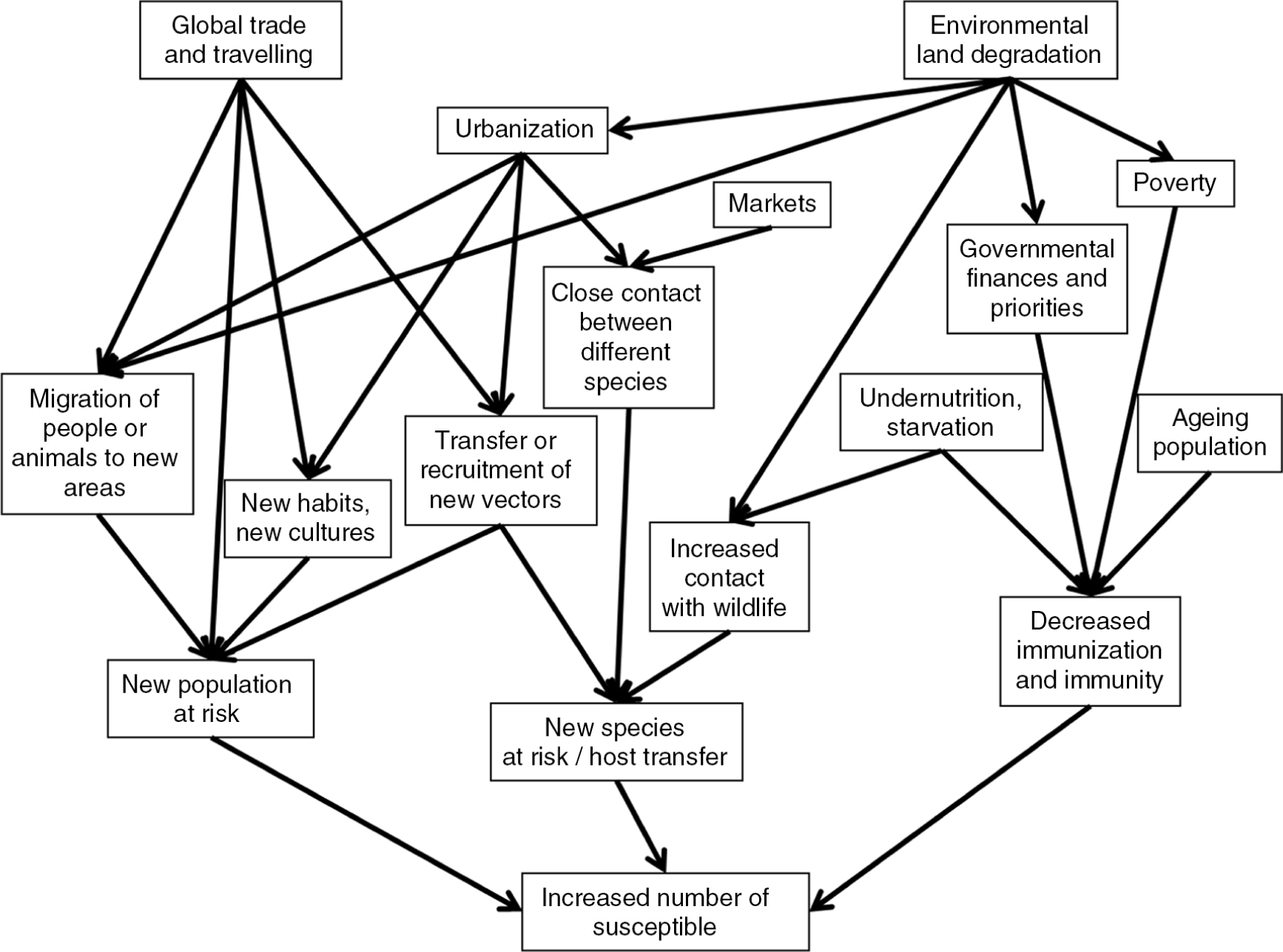

Lindahl and Grace (2015) considered the factors that impact the number of individuals susceptible to infection, the factors leading to increased exposure and the factors related to increased risk of infectivity. A new population can become at risk for an infection if a new pathogen is transferred to a previously uninfected area. This both can occur as a result of migration or travel over a distance where a pathogen is brought by an infected individual, in a vector, or in contaminated products, and it can be a slow progression into neighbouring areas, by animal, human or vector movements. A cultural exchange may also cause a population to adopt new habits and acquire new risks. The framework showing factors contributing to increased susceptible populations is shown in Figure. 1.

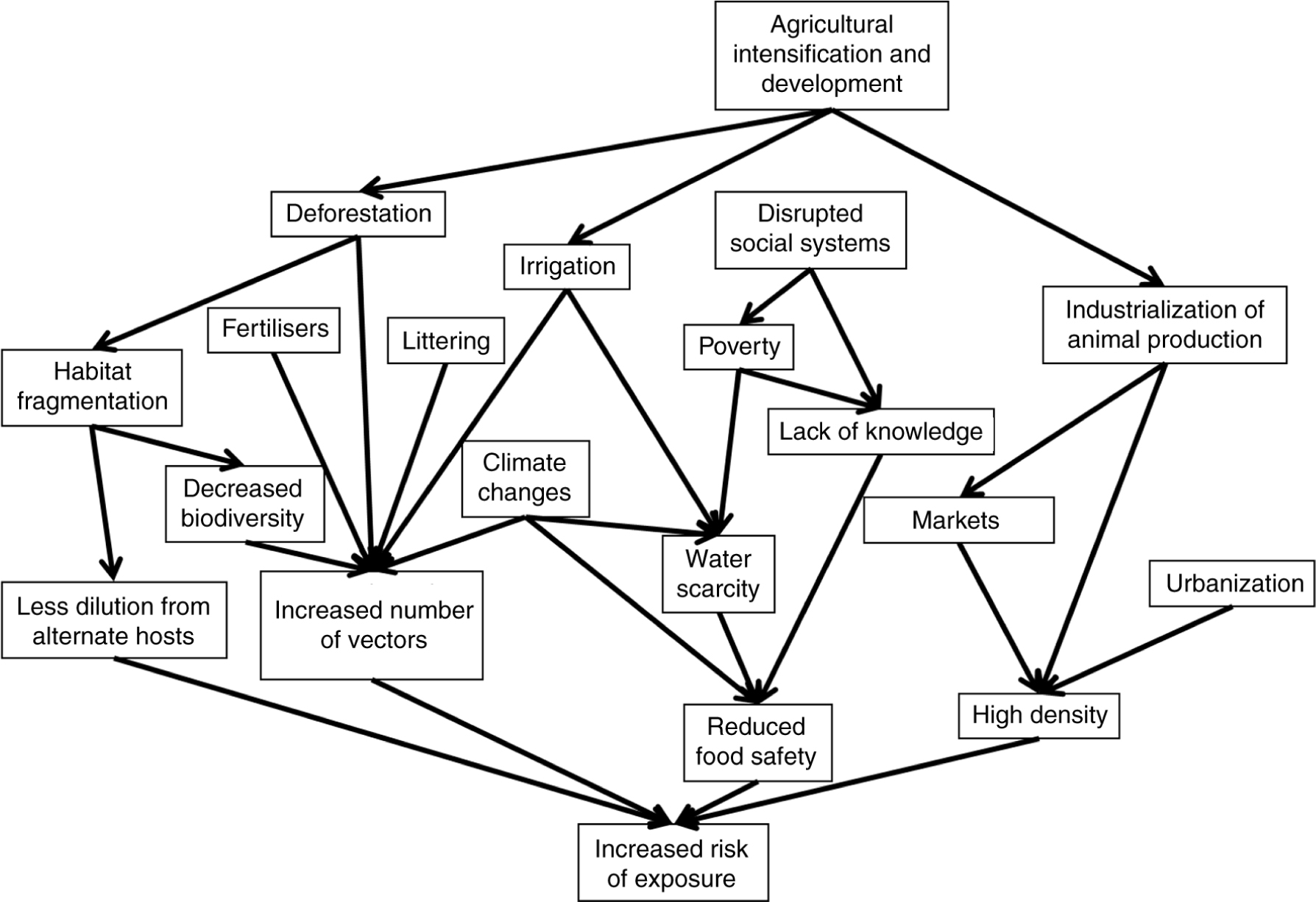

A major factor in the risk of exposure to a pathogen already in place is the pattern of interaction between individuals, which depends on the population density and behaviour. Increasing urbanization, as well as intensified animal keeping, increases exposure. A framework showing factors contributing to increased exposure is shown in Figure. 2.

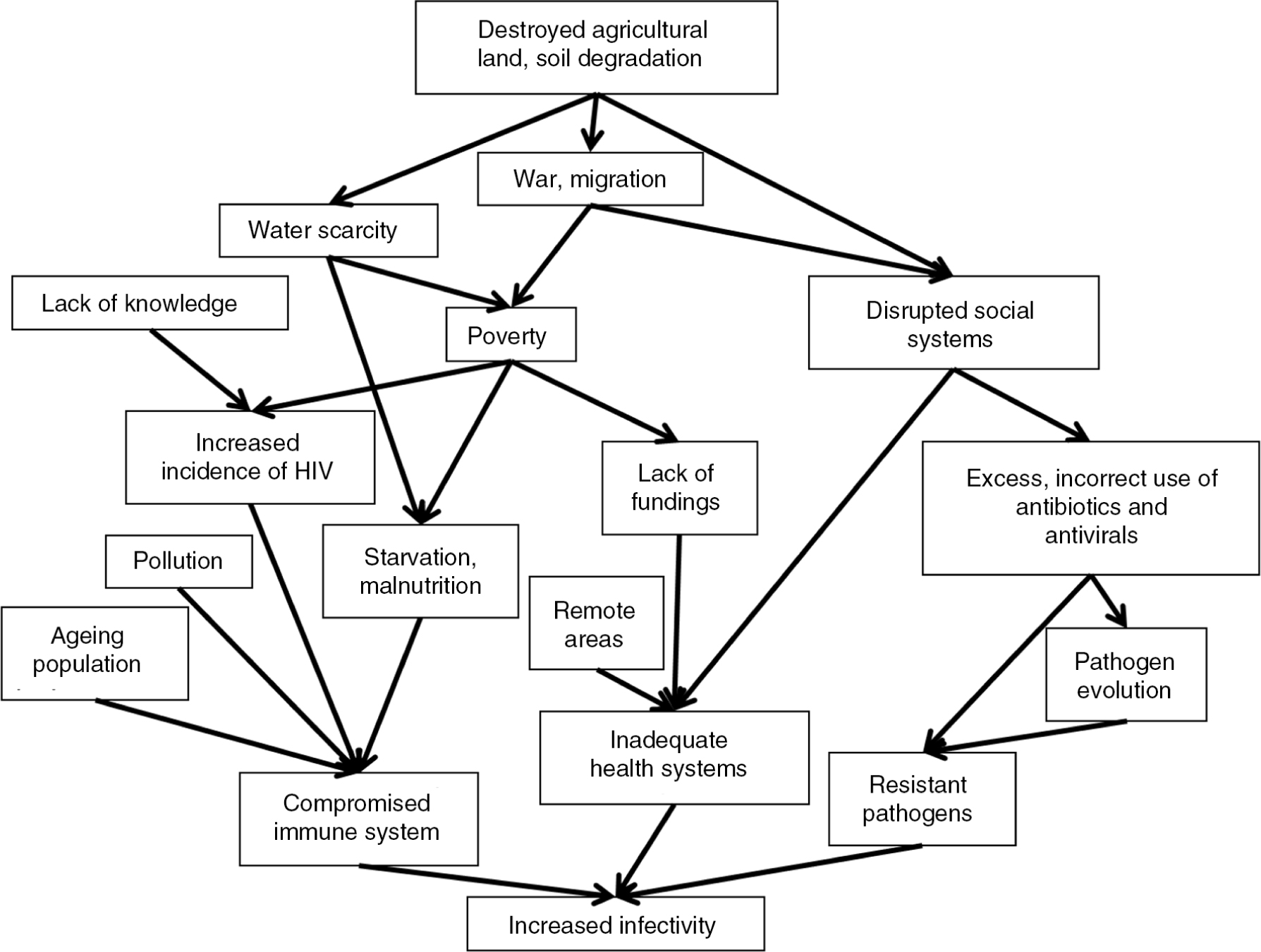

How infectious an individual is following an infection, and for how long, is dependent on factors in the infected individual, on the pathogen and the possibility of veterinary and medical care to cure the infection. A framework showing factors contributing to increased infectivity is shown in Figure. 3.

Signs & Symptoms [edit | edit source]

Depending on the etiology (e.g. virus, bacteria), the systems involved (e.g. respiratory, cardiovascular, central nervous system) and stage of disease (e.g. acute, chronic), the clinical manifestations of Communicable Diseases will vary widely and may be local to the site of infection (e.g. cellulitis, abscess) or systemic (most often fever). Manifestations may also develop in multiple organ systems and severe, generalised infections may have life-threatening manifestations (e.g. sepsis, septic shock). [11] [5]

Cardiovascular [edit | edit source]

- Tachycardia

- Bradycardia

- Hypotension

- Tachypnea

- Dyspnea

- Cough

- Hoarseness

- Sore Throat

- Nasal Drainage

- Sputum Production

- Oxygen Desaturation

- Decreased Activity/Exercise Tolerance

Central Nervous System [edit | edit source]

- Altered Consciousness

- Confusion

- Delirium

- Stupor

- Coma

- Seizure

- Headache

- Photophobia

- Memory Loss

- Stiff Neck

- Myalgia

Endocrinology[edit | edit source]

- Increased Thyroid-stimulating Hormone

- Increased Vasopressin

- Increased Insulin

- Increased Glucagon

- Hyperglycemia

- Hypoglycemia

Gastrointestinal[edit | edit source]

- Nausea

- Vomiting

- Diarrhea

Geniturinary[edit | edit source]

- Haematuria

- Dysuria

- Oliguria

- Proteinuria

- Urgency

- Frequency

Haematology[edit | edit source]

- Increased Immature Neutrophils

- Increased Mature Neutrophils

- Release Granulocytes

- Increased Leukocytes

- Thrombocytopenia

Integumentary[edit | edit source]

- Purulent Drainage

- Skin Rash

- Red Streaks

- Bleeding from Gums

- Bleeding into Joints

- Erythema

- Joint Effusions

Systemic[edit | edit source]

- Fever

- Chills

- Malaise

- Enlarged Lymph Nodes

- Changes in Mental Status

- Fatigue

- Lethargy

- Altered Appetite

Implications for Physiotherapy[edit | edit source]

As healthcare workers, it is important that we recognise the symptoms of the most important infectious diseases and direct those affected to appropriate treatment as quickly as possible. It is also important to be aware of the role physiotherapy has in treating and advising patients presenting with these diseases. For example:

- the benefits of exercise for patients with Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV)[12][13],

- treatment of motor-function disability following cerebral malaria[14],

- reduced risk of ventilator-associated pneumonia[15][16].

- use of mechanical airway clearance in patients with pulmonary tuberculosis[17]

- rehabilitation of disabilities resulting from diseases the Zika Virus[18] and Ebola Virus[19][20]

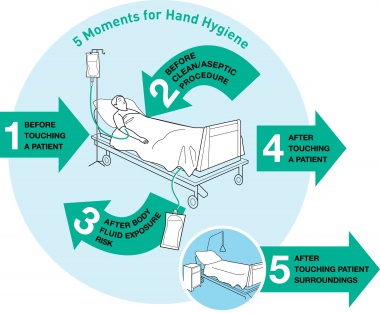

The statistics related to HealthCare Associated Infections make it clear that Hand Hygiene in the healthcare environment is extremely important. As physiotherapists, we need to learn how to use the alcohol hand rubs effectively and utilise these frequently. The WHO Guidelines identify five moments for Hand Hygiene:

- Before Touching the Patient Why? Protect the patient from acquiring germs that might be on your hands. Clean your hands prior to personal care activities like bathing, dressing, brushing and oral care, as well as non-invasive observations (taking vital signs) and treatments.

- Before Clean/Aseptic Procedure Why? Protect the patient from harmful germs, including their own, that could enter the body during procedures like needle insertions, medication administration and connecting to invasive medical devices like EEGs.

- After Body Fluid Exposure Risk Why? Protect yourself and the patient’s surroundings from harmful patient germs generated via contact with fluids like blood, saliva, mucous, semen, tears or urine.

- After Touching a Patient Why? Protect yourself and the immediate environment from harmful patient germs. After you touch a patient, you could have microorganisms on your hands that would get passed on to other patients.

- After Touching Patient Surroundings Why? Protect yourself and the immediate surroundings from harmful patient germs.

[21] [21]

|

[22] |

Resources[edit | edit source]

Guidelines and Policy

- World Confederation for Physical Therapy. Policy Statement Infection Control & Prevention. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4353090/. [Accessed: 11 Jan 2017]

Open Access Journals

- Antimicrobial Resistance & Infection Control. Published by one of the largest reputable open-access journal providers, BioMed Central, ARIC investigates the factors behind the development of multidrug resistant pathogens.

- International Journal of Infectious Diseases. This official journal of the International Society of Infectious Diseases became completely open access at the start of 2014 and publishes important research each month.

- Emerging Infectious Diseases. The fourth most influential journal for infectious disease research, this monthly publication from the Centers for Disease Control has been disseminating key HIV/AIDS research for decades, as well as information on other infectious diseases.

Consensus Papers & Relevant Articles

- Mills A, Shillcutt S. Copenhagen consensus challenge paper on communicable diseases. Copenhagen Consensus Challenge Paper. 2004.

- Barber NC, Stark LA. Online resources for understanding outbreaks and infectious diseases. CBE-Life Sciences Education. 2015 Mar 2;14(1):fe1

Hand Hygiene Resources

- Centers for Disease Control & Prevention. Hand Hygiene in Healthcare Settings. https://www.cdc.gov/handhygiene/index.html [Accessed: 12 Jan 2017]

- World Health Organisation. Five Moments for Hand Hygiene. http://www.who.int/gpsc/tools/Five_moments/en/. [Accessed: 05 Jan 2017]

- World Health Organisation. SAVE LIVES: Clean Your Hands. http://www.who.int/gpsc/5may/en/. [Accessed: 07 Jan 2017]

References[edit | edit source]

- ↑ World Health Organization. Communicable Disease Prevention, Control and Eradication. http://www.who.int/countries/eth/areas/cds/en/ (accessed 21 Dec 2016)

- ↑ World Health Organization. Infectious Diseases. http://www.who.int/topics/infectious_diseases/en/ (accessed 21 Dec 2016)

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 3.4 3.5 3.6 3.7 3.8 Lindahl JF, Grace D. The consequences of human actions on risks for infectious diseases: a review. Infection ecology & epidemiology. 2015;5. Available at: http://www.infectionecologyandepidemiology.net/index.php/iee/article/view/30048

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 Weiss RA, McMichael AJ. REPRINT H. Health of People, Places and Planet: Reflections based on Tony McMichael’s four decades of contribution to epidemiological understanding. 2015 Jul 31;10(12):431.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 Goodman CC, Fuller KS. Pathology: implications for the physical therapist. Elsevier Health Sciences; 2014 Nov 5.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 6.3 Mayo Clinic. Infectious Diseases. http://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/infectious-diseases/symptoms-causes/dxc-20168651 (accessed 19 Dec 2016).

- ↑ Centre for Disease Control. Parasites. https://www.cdc.gov/parasites/ {Accessed: 11 Dec 2016)

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 8.2 Merck Manuals Professional Version. Host Defense Mechanisms Against Infection. http://www.merckmanuals.com/professional/infectious-diseases/biology-of-infectious-disease/host-defense-mechanisms-against-infection. [Accessed: 23 Dec 2016]

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 9.2 World Health Organization. Antimicrobial resistancehttp://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs194/en/ [Accessed: 10 Jan 2017]

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 Boundless. “Predisposing Factors.” Boundless Microbiology Boundless, 08 Aug. 2016. Retrieved 12 Jan. 2017 from https://www.boundless.com/microbiology/textbooks/boundless-microbiology-textbook/epidemiology-10/disease-patterns-132/predisposing-factors-674-10797/

- ↑ Merck Manual Professional Version. Manifestations of Infection. http://www.merckmanuals.com/professional/infectious-diseases/biology-of-infectious-disease/manifestations-of-infection (accessed 16 Dec 2016)

- ↑ O’Brien KK, Solomon P, Baxter L, Casey A, Tynan AM, Wu J, Zack E. Evidence-informed recommendations in rehabilitation for older adults living with HIV: implications for physiotherapy practice. Physiotherapy. 2015 May 1;101:e1420-1.

- ↑ Brown D, Claffey A, Harding R. Evaluation of a physiotherapy-led group rehabilitation intervention for adults living with HIV: referrals, adherence and outcomes. AIDS care. 2016 Dec 1;28(12):1495-505.

- ↑ Konno K, Chibwana S, Takata Y. Intensive physiotherapy with subsequent community-based rehabilitation: two cases of cerebral malaria in rural areas of Malawi. Journal of Physical Therapy Science. 2019;31(1):112-5.

- ↑ Pattanshetty RB, Gaude GS. Effect of multimodality chest physiotherapy in prevention of ventilator-associated pneumonia: a randomized clinical trial. Indian journal of critical care medicine: peer-reviewed, official publication of Indian Society of Critical Care Medicine. 2010 Apr;14(2):70.

- ↑ Ntoumenopoulos G, Presneill J, McElholum M, Cade J. Chest physiotherapy for the prevention of ventilator-associated pneumonia. Intensive care medicine. 2002 Jul 1;28(7):850-6.

- ↑ Moses R, Ricketts H, Ricketts W, Hart N. Mechanical airway clearance in patients with pulmonary tuberculosis: is it indicated, contraindicated or used with caution?. Physiotherapy. 2016 Nov 1;102:e195-6.

- ↑ Michel D. Landry, Sudha R. Raman, Kai Kennedy, Janet Prvu Bettger, Dawn Magnusson; Zika Virus (ZIKV), Global Public Health, Disability, and Rehabilitation: Connecting the Dots…, Physical Therapy, Volume 97, Issue 3, 1 March 2017, Pages 275–279

- ↑ Howlett PJ, Walder AR, Lisk DR, Fitzgerald F, Sevalie S, Lado M, N’jai A, Brown CS, Sahr F, Sesay F, Read JM. Case Series of Severe Neurologic Sequelae of Ebola Virus Disease during Epidemic, Sierra Leone. Emerging infectious diseases. 2018 Aug;24(8):1412.

- ↑ Okumoto L, Flaugher M. Ebola and physical therapy in the acute care setting. Physiotherapy. 2015 May 1;101:e1135.

- ↑ DebMed. 5 Moments vs. 2 Moments. What is enough when it comes to Hand Hygiene?. http://blog.debmed.com/blog/5-moments-vs.-2-moments.-what-is-enough-when-it-comes-to-hand-hygiene (accessed 2 Dec 2016).

- ↑ Huang Shouyung. WHO Hand Hygiene Video https://youtu.be/s08yiZBSGOw (accessed 2 Dec 2016).