Tuberculosis

Original Editors -Lori McGarrh from Bellarmine University's Pathophysiology of Complex Patient Problems project.

Top Contributors - Lori McGarrh, Kim Jackson, Lucinda hampton, Admin, Arnold Fredrick D'Souza, Elaine Lonnemann, Naomi O'Reilly, WikiSysop, Shaimaa Eldib, Nupur Smit Shah, 127.0.0.1, Laura Ritchie and Wendy Walker

Introduction[edit | edit source]

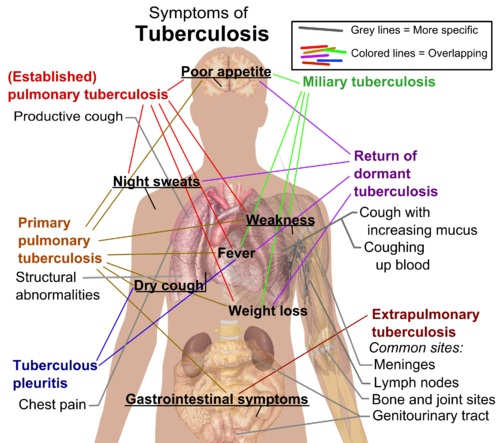

Tuberculosis (TB) is an ancient human disease caused by Mycobacterium tuberculosis. It is an airborne pathogen and is extremely contagious. TB mainly affects the lungs, making pulmonary disease, the most common presentation. However, TB is a multi-systemic disease with a variable presentation. The organ system most commonly affected includes the respiratory system, the gastrointestinal (GI) system, the lymphoreticular system, the skin, the central nervous system, the musculoskeletal system, the reproductive system, and the liver.[1]

- Tuberculosis is a preventable and treatable infectious disease and is still one of the major contributors of morbidity and mortality in developing countries where we are still struggling to provide adequate access to care.

- TB was one of the top 10 causes of death worldwide in 2018 (being the leading killer of people with HIV and a major cause of deaths related to antimicrobial resistance).

- In 2018, there were an estimated 10 million new TB cases worldwide, of which 5.7 million were men, 3.2 million were women and 1.1 million were children. People living with HIV accounted for 9% of the total.

- Eight countries accounted for 66% of the new cases: India, China, Indonesia, the Philippines, Pakistan, Nigeria, Bangladesh, and South Africa.

- In 2018, 1.5 million people died from TB, including 251,000 people with HIV.

- Globally, the TB mortality rate fell by 42% between 2000 and 2018.[2]

- Before the 1940s, tuberculosis was the leading cause of death in the United States.[3]

Definition/Description[edit | edit source]

Tuberculosis (TB) is an inflammatory, infectious disease that is spread by bacteria called mycobacterium tuberculosis. Pulmonary tuberculosis is a systemic disease that most commonly affects the lungs.[3] Eventually, TB could spread to other organ systems, which it then becomes extrapulmonary tuberculosis. TB can be placed into the following two categories:

- Primary Tuberculosis[3] (Dormant or Latent) – Although a person’s body can be infected with mycobacterium tuberculosis, they may not be showing clinical signs and symptoms. Most people have healthy immune systems that will never allow TB to take over their bodies.

- Secondary Tuberculosis[3] (Active) – This will develop after the immune system of a person is lowered. Reinfection will occur and the person will start to show clinical signs and symptoms.

Aetiology[edit | edit source]

- Tuberculosis is spread by airborne particles known as droplet nuclei (spread when infected people sneeze, laugh, speak, sing, or cough).

- In order to contract this disease, a person has to have prolonged exposure with an infected person in an enclosed space.

- It is suspected that there could be a genetic component to susceptibility and resistance, but that has yet to be proven.

- In some countries, it is common for bovine TB to be spread through unpasteurised milk and other dairy products due to cattle with tuberculosis.

The organism has several unique features compared to other bacteria such as the presence of several lipids in the cell wall including mycolic acid, cord factor, and Wax-D. The high lipid content of the cell wall is thought to contribute to the following properties of M. tuberculosis infection:

- Resistance to several antibiotics

- Difficulty staining with Gram stain and several other stains

- Ability to survive under extreme conditions such as extreme acidity or alkalinity, low oxygen situation and intracellular survival(within the macrophage)[1]

- A reason the bacteria is able to be dormant in someone for years and is able to survive for months in sputum that is not exposed to sunlight and is trapped within the body (primary TB). Once the person’s resistance is lowered, the TB can become active (secondary TB). This could be due to advancing age, alcoholism, cancer, or immunosuppression.[3]

Epidemiology[edit | edit source]

Geographic Distribution[edit | edit source]

Tuberculosis is present globally. However; developing countries account for a disproportionate share of tuberculosis disease burden. The bulk of the global burden of new infection and tuberculosis death is borne by developing countries with 6 countries: India, Indonesia, China, Nigeria, Pakistan, and South Africa, accounting for 60% of TB death in 2015, Several countries in Asia, Africa, Eastern Europe, and Latin and Central America continue to have an unacceptably high burden of tuberculosis.

In more advanced countries, high burden tuberculosis is seen among recent arrivals from tuberculosis-endemic zones, health care workers, and HIV-positive individuals. Use of immunosuppressive agents such as long-term corticosteroid therapy has also been associated with an increased risk.

Other Major Risk Factors[edit | edit source]

- Socio-economic factors: Poverty, malnutrition, wars

- Immunosuppression: Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV), chronic immunosuppressive therapy (steroids, monoclonal antibodies against tumor necrotic factor), a poorly developed immune system (children, primary immunodeficiency disorders)

- Occupational: Mining, construction workers, pneumoconiosis (silicosis)[1]

The WHO estimates that 10.4 million individuals became ill with TB and 1.7 million died in 2016. Despite the fall in mortality rate of 3% per year, TB remains the ninth leading cause of death worldwide, counting 1.3 million TB deaths among HIV-negative people and almost 400,000 deaths among HIV-positive people.[4]

TB in Prisons[edit | edit source]

- The level of TB in prisons has been reported to be up to 100 times higher than that of the civilian population.

- Cases of TB in prisons may account for up to 25% of a country’s burden of TB.

- Late diagnosis, inadequate treatment, overcrowding, poor ventilation and repeated prison transfers encourage the transmission of TB infection.

- HIV infection and other pathology more common in prisons (e.g. malnutrition, substance abuse) encourage the development of active disease and further transmission of infection.

- Multi-drug resistant tuberculosis (MDR-TB) in prisons High levels of MDR-TB have been reported from some prisons with up to 24% of TB cases suffering from MDR forms of the disease.[5]

Characteristics/Clinical Presentation[edit | edit source]

A chronic cough, haemoptysis, weight loss, low-grade fever, and night sweats are some of the most common physical findings in pulmonary tuberculosis.

Secondary tuberculosis differs in clinical presentation from the primary progressive disease. In secondary disease, the tissue reaction and hypersensitivity is more severe, and patients usually form cavities in the upper portion of the lungs.

Pulmonary or systemic dissemination of the tubercles may be seen in active disease. Disseminated tuberculosis may also be seen in the spine, the central nervous system, or the bowel.[1]

There are usually no symptoms of tuberculosis during the first year of exposure. This is when the disease would be the most curable. Symptoms suggestive of TB include[3]:

- Productive cough that lasts longer than 3 weeks

- Weight Loss

- Fever

- Night sweats

- Fatigue

- Malaise

- Anorexia

- Rales could be heard in the lobes of involvement in the lungs

- Bronchial Breath Sounds

- Dull chest pain, tightness, or discomfort[6]

- Dyspnea[6]

- Haemoptysis (late-stage symptom)

Systemic Involvement[edit | edit source]

10%-15% of tuberculosis is extra-pulmonary. It can spread through the blood vessels from organ to organ and/or the lymphatic system. Extra-pulmonary TB can involve the:[6]

- Kidneys

- Bone Growth Plates

- Lymph Nodes

- Meninges

- Hip Joints - can cause avascular necrosis of the hip

- Elbows

- Vertebrae (Pott's Disease)

Associated Co-morbidities[edit | edit source]

- HIV/AIDS - due to comprised immunosuppressive system

- Rheumatoid Arthritis[6] - due to immunosuppressive treatments

- Diabetes Mellitus

- End-stage Renal Disease

- Gastrointestinal Disease[6]

- Alcoholism

- Cancer - due to chemotherapy, radiation, or steroid therapy

- Malnutrition

Additional Risk Factors[6][edit | edit source]

- Healthcare workers

- Older adults

- Homeless people

- Overcrowded housing

- People who are incarcerated

- Immigrants

- Children under the age of 5

Medications[edit | edit source]

Once tuberculosis is diagnosed, all active cases are treated and many inactive cases are treated. It is unclear if preventive treatment is helpful in people with latent TB. However, it is hoped that the disease will be less likely to become active later in life once the immune system is more likely to be compromised.[3]

There are currently 10 drugs that are approved by the FDA to treat TB. The following medications are first-line anti-TB agents that form the core medications given[7]:

- Isoniazid

- Rifampin

- Pyrazinamid

- Ethambutol

The recommended time for taking the medication is 6-9 months. Blood work should be performed monthly to check on the liver and make sure it is handling the medicine okay.[7]

- Many people are not compliant with taking their medicine daily for 9 months. Many people will begin to feel better, so they will decide to stop administering the medicine.

- Compliance is also a problem with homeless people, alcoholics, and drug users.

- If treatment is not completed, multi-drug resistant TB can form which means the person will now be resistant to the medication taken previously.[3]

- Multi-drug resistant TB has an even more complicated treatment than before.

- Some people require a pneumonectomy or chemotherapy along with two or more drugs that are used at the same time.[6]

- Directly Observed Therapy (DOT) should always be used when treating multi-drug resistant TB to ensure the subject is practicing proper compliance.

- Treatments are the same for pulmonary and extra-pulmonary TB.

Multidrug-Resistant Tuberculosis (MDR-TB)[edit | edit source]

Tuberculosis (TB) can develop resistance to the antimicrobial drugs used to cure the disease. Multidrug-resistant TB (MDR-TB) is TB that does not respond to at least isoniazid and rifampicin, the 2 most powerful anti-TB drugs. Inappropriate or incorrect use of antimicrobial drugs, or use of ineffective formulations of drugs (such as use of single drugs, poor quality medicines or bad storage conditions), and premature treatment interruption can cause drug resistance, which can then be transmitted, especially in crowded settings such as prisons and hospitals. Treatment options are limited and expensive, recommended medicines are not always available, and patients experience many adverse effects from the drugs. In some cases even more severe drug-resistant TB may develop.[8]

Extensively Drug-Resistant Tuberculosis (XDR-TB)[edit | edit source]

XDR-TB, an abbreviation for extensively drug-resistant tuberculosis (TB), is a form of TB which is resistant to at least four of the core anti-TB drugs. XDR-TB involves resistance to the two most powerful anti-TB drugs, isoniazid and rifampicin, also known as multidrug-resistance (MDR-TB), in addition to resistance to any of the fluoroquinolones (such as levofloxacin or moxifloxacin) and to at least one of the three injectable second-line drugs (amikacin, capreomycin or kanamycin).[9]

MDR-TB and XDR-TB both take substantially longer to treat than ordinary (drug-susceptible) TB, and require the use of second-line anti-TB drugs, which are more expensive and have more side-effects than the first-line drugs used for drug-susceptible TB.[8][9]

TB Screening[edit | edit source]

Approximately 33% of the world's population has latent tuberculosis infection (LTBI). For this reason, screening for Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection is essential for public health. People with LTBI are at risk for developing active tuberculosis (TB) and becoming infectious.

- The greatest risk for progression occurs during the first two years of infection.

- The goal of testing for LTBI is to identify individuals who are at high risk of developing active TB.

- The decision to test should presuppose a decision to treat if the result is positive.

- The tuberculin skin test (TST) and the interferon-gamma release assay (IGRA) are the current methods for screening and are based on the measurement of adaptive host immune response.[10]

BCG Vaccine [edit | edit source]

The Bacille Calmette-Guérin (BCG) vaccine has existed for 80 years and is one of the most widely used of all current vaccines, reading >80%of neonates and infants in countries where it is part of the national childhood immunization programme.

BCG vaccine has a documented protective effect against meningitis and disseminated TB in children.

It does not prevent primary infection and does not prevent reactivation of latent pulmonary infection, the principal source of bacillary spread in the community. The impact of BCG vaccination on transmission of Mtb is therefore limited.

The CDC and the American Academy of Paediatrics recommend that all children adopted from high-risk countries who have received the BCG vaccine should act as if they have never received it.[6] All children should be given a skin test and treated whether it is dormant or active.

The Mantoux tuberculin skin test is performed by having 0.1ml of tuberculin purified protein derivative (PPD) injected into the inner layer of the forearm.[11] This will determine if the body’s immune response has been activated by the presence of the bacillus. Upon injection, the skin will elevate around 6-10 mm in diameter. 48 to 72 hours later, the person should have their skin test reaction read. A positive test could reveal a palpable, swollen, hardened, or raised area that should be measured in millimetres. Redness is not measured.[11]

Physical Therapy Management[edit | edit source]

All physical therapists should be aware of the proper personal protective equipment (PPE) that should be worn. There is a specialised mask that is worn that has been sized to specifically fit your face.[6]

- Pulmonary Tuberculosis People with pulmonary TB are typically not treated in physical therapy because medications are vital for curing TB. However, therapists are able to provide percussion and postural drainage to clear secretions out of the lung.[12]

- Extrapulmonary Tuberculosis Clients with extra-pulmonary TB are usually not seen in the physical therapy setting. However, patients may present in clinic with musculoskeletal problems with unknown causes or arthritic pain. PT's should be prepared to take a thorough history and a proper examination in order to better identify TB. A patient could also be seen in physical therapy if they have had surgery on their back, in which case the normal rehabilitation protocols would be followed.[12]

It is very important to take a thorough history when TB is suspected. It is important to ask if the person has travelled outside the country recently, their occupation, or if there is any way they have possibly been exposed to someone who could have TB. Recognise your patient's signs and symptoms. Palpation of the lymph nodes could also be informational during an examination. [13]

Differential Diagnosis[edit | edit source]

Tuberculosis is a great mimic and should be considered in the differential diagnosis of several systemic disorders. The following is a non-exhaustive list of conditions to be strongly considered when evaluating the possibility of pulmonary tuberculosis.

- Pneumonia

- Malignancy

- Non-tuberculous mycobacterium

- Fungal infection

- Histoplasmosis

- Sarcoidosis[1]

Prognosis[edit | edit source]

Majority of patients with a diagnosis of TB have a good outcome. This is mainly because of effective treatment. Without treatment mortality rate for tuberculosis is more than 50%.

The following group of patients is more susceptible to worse outcomes or death following TB infection:

- Extremes of age, elderly, infants and young children

- Delay in receiving treatment

- Radiologic evidence of extensive spread.

- Severe respiratory compromise requiring mechanical ventilation

- Immunosuppression

- Multi-drug Resistant (MDR) Tuberculosis[1]

References[edit | edit source]

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 1.5 Adigun R, Bhimji S. Tuberculosis. StatPearls 2017.Available from:https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK441916/ (last accessed 8.3.2020)

- ↑ WHO GLOBAL TUBERCULOSIS REPORT 2019 Available from:https://www.who.int/tb/publications/factsheet_global.pdf?ua=1 (last accessed 8.3.2020)

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 3.4 3.5 3.6 Goodman C, Fuller K. Pathology: Implications for the Physical Therapist. 3rd edition. In: Ikeda, B, Goodman, C. The Respiratory System. St. Louis, MO: Saunders; 2009: 752-758.

- ↑ Matteelli A, Rendon A, Tiberi S, Al-Abri S, Voniatis C, Carvalho AC, Centis R, D'Ambrosio L, Visca D, Spanevello A, Migliori GB. Tuberculosis elimination: where are we now?. European Respiratory Review. 2018 Jun 30;27(148):180035. Available from:https://err.ersjournals.com/content/27/148/180035

- ↑ WHO TB in prisons Available from:https://www.who.int/tb/areas-of-work/population-groups/prisons-facts/en/ (last accessed 8.3.2020)

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 6.3 6.4 6.5 6.6 6.7 6.8 Goodman C, Snyder T. Differential Diagnosis for Physical Therapists: Screening for Referral. 4th edition. In: Screening for Pulmonary Disease.. St. Louis, MO: Saunders; 2007: 344-345.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Treatment of Latent Tuberculosis Infection. Atlanta, GA. [Web-Page]. 2010. http://www.cdc.gov/tb/publications/factsheets/treatment/treatmentLTBI.htm. Accessed on March 18, 2011.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 What is multidrug-resistant tuberculosis (MDR-TB) and how do we control it? [Internet]. WHO. World Health Organization; 2018 [cited 2020 Mar 20]. Available from: https://www.who.int/features/qa/79/en/

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 Drug-resistant TB: XDR-TB FAQ [Internet]. WHO. World Health Organization; 2018 [cited 2020 Mar 20]. Available from: https://www.who.int/tb/areas-of-work/drug-resistant-tb/xdr-tb-faq/en/

- ↑ de Lima Corvino DF, Kosmin AR. Tuberculosis Screening. InStatPearls [Internet] 2019 Feb 4. StatPearls Publishing.Available from:https://www.statpearls.com/kb/viewarticle/30655 (last accessed 8.3.2020)

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Tuberculin Skin Testing. Atlanta, GA. [Web-Page]. 2010. http://www.cdc.gov/tb/publications/factsheets/testing/skintesting.htm. Accessed on March 18, 2011.

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 Goodman C, Fuller K. Pathology: Implications for the Physical Therapist. 3rd edition. In: Infectious Diseases of the Musculoskeletal System. St. Louis, MO: Saunders; 2009: 1198-1199.

- ↑ Flicr. Bayberry. http://www.flickr.com/photos/zeping/150247200/