Diabetes

Author- Chester Ryan Azurin

Top Contributors - Chester Ryan Azurin, Admin, Lucinda hampton, Naomi O'Reilly, WikiSysop, Vidya Acharya, Aminat Abolade, Jonathan Wong, 127.0.0.1, Rachael Lowe, Selena Horner, Evan Thomas, Kim Jackson and Amanda Ager

Introduction[edit | edit source]

Diabetes, or diabetes mellitus (DM), is a metabolic disorder in which the body is unable to appropriately regulate the level of sugar, specifically glucose, in the blood, either by poor sensitivity to the protein insulin (type 2), or due to inadequate production of insulin by the pancreas (type 1). There are two main types of diabetes: type 1 and type 2, with Type 2 diabetes accounting for nearly 90% of all diabetes cases, with a worldwide prevalence of 537 million[1].

- In the past 20 years, the magnitude of diabetes has increased dramatically in many parts of the world and the disease is now a worldwide community health problem.

- Diabetes mellitus is associated with numerous systemic complications that affect the retina, heart, brain, kidneys and nerves.

- Evidences strongly support that physiotherapists play a significant role in the prevention, treatment and management of diabetes mellitus and its associated complications[2].

- Physiotherapy management, including exercise prescription and education, help patients participation improve and maintain physical well-being which has a significant impact on their activities of daily living and health-related quality of life[3]

- Diabetes itself is not a high-mortality condition, but it is a major risk factor for other causes of death and has a high attributable burden of disability.

- Diabetes is also a major risk factor for cardiovascular disease, kidney disease and blindness.[4]

Be sure to also read:

Clinically Relevant Anatomy and Pathophysiology[edit | edit source]

DM is broadly classified into three types by etiology and clinical presentation, type 1 diabetes, type 2 diabetes, and gestational diabetes (GDM).[5]

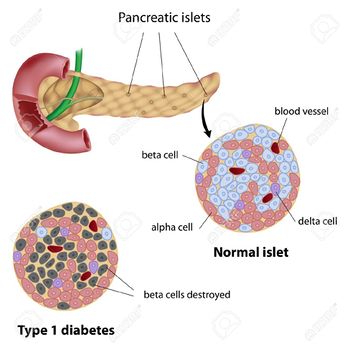

Diabetes Mellitus primarily affects the Islets of Langerhans of the pancreas, where glucagon (from the alpha cells) and insulin (from the beta cells) are produced. Glucagon raises the blood glucose level, while insulin lowers it.

- Type 1 DM (Insulin Dependent) accounts for 5% to 10% of DM and is characterized by autoimmune destruction of insulin-producing beta cells in the islets of the pancreas, the loss of function of the beta cells leads to an absolute insulin deficiency. T1DM is most commonly seen in children and adolescents though it can develop at any age.

- Type 2 DM (Non-insulin Dependent) accounts for around 90% of all cases of diabetes[1]. In T2DM, the response to insulin is diminished, and this is defined as insulin resistance. As such, insulin is ineffective and is initially countered by an increase in insulin production to maintain glucose homeostasis, but over time, insulin production decreases, resulting in T2DM. T2DM is most commonly seen in persons older than 45 years. It is increasingly now seen in children, adolescents, and younger adults due to rising levels of obesity, physical inactivity, and energy-dense diets.

- Gestational Diabetes Mellitus (first detected during pregnancy) can occur anytime during pregnancy. Generally affects pregnant women during the second and third trimesters. According to the American Diabetes Association (ADA), GDM complicates 7% of all pregnancies. Women with GDM and their offspring have an increased risk of developing type 2 diabetes mellitus in the future[5].

Epidemiology[edit | edit source]

Diabetes is a worldwide epidemic.

- With changing lifestyles and increasing obesity, the prevalence of DM has increased worldwide.

- The global prevalence of DM was 425 million in 2017.

- According to the International Diabetes Federation (IDF), in 2015, about 10% of the American population had diabetes. Of these, 7 million were undiagnosed.

- With an increase in age, the prevalence of DM also increases.

- About 25% of the population above 65 years of age has diabetes.[5]

Complications[edit | edit source]

Complications are similar for type 1 and type 2 diabetes patients, yet the frequency or timing of occurrence can vary[6]. Complications from diabetes can be broken up into two categories: microvascular and macrovascular.

Microvascular complications include[7]:

- nervous system damage (neuropathy)

- renal system damage (nephropathy)

- eye damage (retinopathy)

Macrovascular complications include[6]:

- cardiovascular disease

- stroke

- peripheral vascular disease, which may lead to:

- bruises or injuries that do not heal

- gangrene and ultimately, amputation.

The prevalence of microvascular complications is much higher than that of macrovascular complications[6].

Clinical Presentation[edit | edit source]

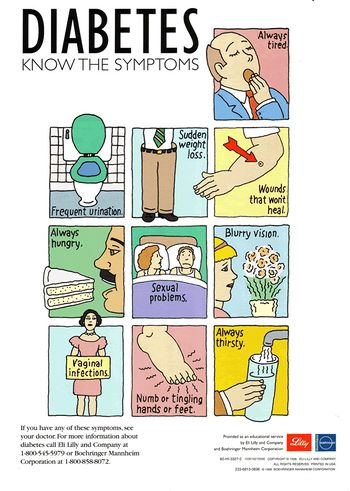

Patients with diabetes mellitus most commonly present with:

- increased thirst,

- increased urination,

- lack of energy and fatigue,

- bacterial and fungal infections

- delayed wound healing.

- may also complain of numbness or tingling in hands or feet or with blurred vision.

- Can have modest hyperglycemia, which can proceed to severe hyperglycemia or ketoacidosis due to infection or stress. T1DM patients can often present with ketoacidosis (DKA) coma as the first manifestation in about 30% of patients[5].

- Persons with DM (usually Type 1) may experience weight loss because of the improper fat metabolism and breakdown of fat stores.

Diagnostic Procedures[edit | edit source]

Fasting glucose level of greater than 126 mg/dl on two separate occasions is considered positive, with fasting defined as no caloric intake for at least 8 hours preceding the test[8].

The strictest procedure is according to the World Health Organization, which states that the diagnosis is positive if "venous plasma glucose concentration is greater than 11.1 mmol/L 2 hours after a 75g glucose tolerance test."

The study by Pooja Bhati et al. suggests that biomarkers of inflammation and endothelial function are correlated with Cardiac Vagal Tone and global Heart Rate Variability (HRV), which indicate some pathophysiological link between subclinical inflammation, endothelial dysfunction and cardiac autonomic dysfunction in Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus[9].

Management[edit | edit source]

For both T1DM and T2DM, the cornerstone of therapy is diet and exercise.

- A diet low in saturated fat, refined carbohydrates, fructose corn syrup, and high in fiber and monounsaturated fats needs to be encouraged.

- Aerobic exercise for a duration of 90 to 150 minutes per week is beneficial.

- The major target in T2DM patients, who are obese, is weight loss[5].

- Weight management, nutritional and diet counselling combined with physical therapy/exercise prescription is ideal.

For Type 1 (insulin dependent) Diabetes, intramuscular administration of insulin is needed. Dosage is always expressed in USP units. Humalog is the fastest acting insulin, acting within 15 minutes. The PZI has the longest peak of 8-20 hours and has the longest total duration of 36 hours. On the other hand, the Lantus is the only one "without peak" and lasts for 24 hours.

For Type 2 (non-insulin dependent) Diabetes, popular oral hypoglycemics include Metformin and Sulfonylureas. Insulin sensitizers such as Rosiglitazone and Pioglitazone are also prescribed.

Physiotherapy Management[edit | edit source]

Therapeutic exercise programs comprise the major aspect of management. Patient education for proper foot care is an essential part of the physical therapy program for diabetic patients.

Exercise Therapy[edit | edit source]

A sound, individually tailored exercise prescription is a cornerstone in the management of Diabetes Mellitus.

Salient Points

- It is recommended that people with DM ought to have a regular aerobic exercise and strength training to reassure positive adaptations in the control of blood glucose concentration, insulin action, muscular strength and exercise tolerance.

- Importance of different modes of exercises in patients with type 2 diabetes - increases uptake of glucose by muscles, improves utilization, altering lipid levels, increases high density lipoprotein and decreases triglyceride and total cholesterol.

- Exercise helps people to overcome disability by preventing, treating and rehabilitating neuromuscular complications like neuropathies, skin break down, foot ulcers, arthritis, other joint pains, frozen shoulder, back pain and osteoarthritis associated with DM.

- Moderate to high levels of different modes of exercises like cardio respiratory fitness exercises, aerobic exercise and progressive resistance exercises are also associated with substantially lower morbidity and mortality in men and women with diabetes.

Guidelines for a sound exercise program are as follows:

- Do not exercise if the blood glucose level is less than 100 mg/dl or greater than 250 mg/dl.

- Preferably, exercise indoor instead of outdoor to minimize the risk of integumentary and musculoskeletal trauma, as well as for the patient to have an immediate access to necessary things to address hypoglycemia, hyperglycemia or diabetic ketoacidosis.

- Patients are highly advised to wear the medical tag for diabetics each time they come out of their house to go somewhere else.

- Always have a carbohydrate snack at hand every exercise session. A glass of orange juice or milk is a good pickup for a patient who is experiencing hypoglycemia.

- Exercise in a comfortable temperature. Never exercise in extreme temperatures.

- For Type 1 (Insulin Dependent) patients, never exercise during the peak times of insulin. Collaborate with the nurse in charge for the patient regarding the type of insulin administered.

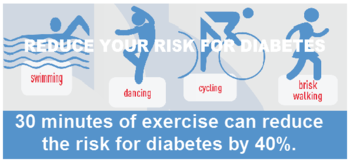

- Type 2 diabetics are advised to have an average of 30 minutes of exercise duration per session.

- Always wear proper footwear and exercise in a safe environment.

- Type 1 diabetics may need to reduce insulin or increase food intake prior to the start of an exercise program. Physical Therapists must coordinate with the referring physician for this case.

- During prolonged exercise duration, 10-15 grams of carbohydrate snack is recommended for every 30 minutes.

- Clients who are on Sulfonylureas are red flags because it can cause exercise-induced hypoglycemia. Closely coordinate with the referring physician if this was missed prior to referral.

- Menstruating women need to increase insulin during menses, especially if they're not active.

- There should be no short-acting insulin injections close to the muscles to be exercised within one hour of exercise.

- Patients should eat 2 hours before exercising. If planning to exercise after meal, patients must wait 1 hour prior to start.

- Patients must always carry their own portable blood glucose monitor. They must check their glucose levels before and after exercise.

- Patients are advised to drink 17 oz. of fluid before exercise.

- If blood glucose is less than 100 mg/dl but not less than 70mg/dl, the physical therapist may provide carbohydrate snack and then recheck the glucose level after 15 minutes.

- Make sure exercise doesn't contribute unnecessary stress to the patient. Stress increases insulin requirements. A gradual progression from aerobic and resístance exercises is the key.

- Avoid exercising late at night.

- If faced with an unexpected and difficult situation wherein the physical therapist is in doubt whether the patient is experiencing hyperglycemia or hypoglycemia, always give a glass of orange juice or milk, or a carbohydrate snack. This is the safest action because this can relieve hypoglycemia (if it is indeed) and cannot harm if it is hyperglycemia.

- Exercise five times a week as a maintenance (or at least every other day) and at the same schedule / time, preferably.

- As much as possible, patient must not exercise alone, so that there will always be someone to help in unexpected situations.

- Good examples of carbohydrate snacks (10-15 grams of carbohydrates) are half a cup of fruit juice or cola, 8 oz. of milk, 2 packets of sugar, 2 oz. tube of honey or cake deco gel.

Diabetics are more prone to hypoglycemia than hyperglycemia during exercise. Watch for classic Signs and Symptoms

Diabetic Ketoacidosis (DKA) - patient might experience abdominal pain, anorexia, nausea, vomiting or diarrhea. This occurs more in children. Patient will have confusion and dull mental state which can lead to coma. There is an increase in pulse rate, yet weak. There is an initial deep and rapid breathing which could lead to Kussmaul respiration. Cardinal sign is a fruity or acetone breath. Urine output is increased and the glucose level is extremely high (greater than 300 mg/dl). Ketones are high and pH is acidotic (less than 7.3). The skin is warm and dry. Onset is rapid, which is less than 24 hours.

Hyperglycemia - there are no gastrointestinal symptoms, usually occur in adults with underlying chronic disease and the patient is also in a dull, confused mental state. Skin is warm and dry, pulse and respiratory rate are high, ketone and pH level are normal, relatively high glucose level and the onset is slow (may take days).

Hypoglycemia can occur with all ages. The patient may feel hungry with difficulty in concentration and coordination which could eventually lead to coma. Skin is cold and clammy, there is profuse sweating, increased pulse rate, shallow respiration, considerably low glucose level, ketones and pH are normal and the onset is rapid.

Resources[edit | edit source]

- WHO. Diabetes Programme. The World Health Organisataion [accessed 18 July 2016]

- WCPT (2011) Diabetes

References[edit | edit source]

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Ahmad E, Lim S, Lamptey R, Webb DR, Davies MJ. Type 2 diabetes. The Lancet. 2022 Nov 19;400(10365):1803-20.

- ↑ Harris-Hayes M, Schootman M, Schootman JC, Hastings MK. The Role of Physical Therapists in Fighting the Type 2 Diabetes Epidemic. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 2020 Jan;50(1):5-16. doi: 10.2519/jospt.2020.9154. Epub 2019 Nov 28. PMID: 31775555; PMCID: PMC7069691.

- ↑ Gelaw AY. Exercise and Diabetes Mellitus. Diabetes Food Plan. 2018 Jul 11;167.Available from:https://www.intechopen.com/books/diabetes-food-plan/exercise-and-diabetes-mellitus (last accessed 22.10.2020)

- ↑ Bloom, D.E., Cafiero, E.T., Jané-Llopis, E., Abrahams-Gessel, S., Bloom, L.R., Fathima, S., Feigl, A.B., Gaziano, T., Mowafi, M., Pandya, A., Prettner, K., Rosenberg, L., Seligman, B., Stein, A.Z., & Weinstein, C. (2011). The Global Economic Burden of Noncommunicable Diseases. Geneva: World Economic Forum</ref>.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 5.3 5.4 Goyal R, Jialal I. Diabetes Mellitus Type 2.2019 Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK513253/(last accessed 21.10.2020)

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 Deshpande AD, Harris-Hayes M, Schootman M. Epidemiology of diabetes and diabetes-related complications. Phys Ther. 2008 Nov;88(11):1254-64. doi: 10.2522/ptj.20080020. Epub 2008 Sep 18. PMID: 18801858; PMCID: PMC3870323.

- ↑ American Diabetes Association. Diagnosis and classification of diabetes mellitus. Diabetes Care. 2006 Jan;29 Suppl 1:S43-8. PMID: 16373932.

- ↑ American Diabetes Association. Diagnosis and classification of diabetes mellitus. Diabetes Care. 2010 Jan;33 Suppl 1(Suppl 1):S62-9. doi: 10.2337/dc10-S062. Erratum in: Diabetes Care. 2010 Apr;33(4):e57. PMID: 20042775; PMCID: PMC2797383.

- ↑ Bhati P, Alam R, Moiz JA, Hussain ME. Subclinical inflammation and endothelial dysfunction are linked to cardiac autonomic neuropathy in type 2 diabetes. Journal of Diabetes & Metabolic Disorders. 2019 Dec;18(2):419-28.