Diabetes Mellitus Type 2

Original Editors - Kara Casey and Josh Rose from Bellarmine University's Pathophysiology of Complex Patient Problems project.

Top Contributors - Kara Casey, Deirion Sookram, Ross Munro, Admin, Uchechukwu Chukwuemeka, Lucinda hampton, Elaine Lonnemann, Ahmed M Diab, WikiSysop, Kim Jackson, 127.0.0.1, Rachael Lowe, Wendy Walker, Evan Thomas, Michelle Lee, Tarina van der Stockt, Shaimaa Eldib, Amanda Ager, Kirenga Bamurange Liliane, Jonathan Wong and Laura Ritchie

Definition/Description[edit | edit source]

Diabetes is caused by a problem in the way your body makes or uses insulin[1]. Insulin moves blood sugar (glucose) into cells where it is stored and later used for energy. There are two main types of diabetes: type 1 and type 2 [1]. Type 1 diabetes is also called insulin dependent diabetes mellitus (IDDM), whereas Type 2 diabetes is also called adult onset diabetes or non-insulin dependent diabetes mellitus (NIDDM)[1]. Diabetes is a chronic condition that affects how the body metabolizes glucose[1]. With type 2 diabetes, your fat, liver, and muscle cells do not respond correctly to insulin, known as insulin resistance[1]. As a result, blood sugar does not get transported into these cells to be stored for energy and builds up in the bloodstream; this is known as hyperglycemia[1].

Etiology/Causes/Pathogenesis[edit | edit source]

In a healthy person, blood glucose levels are normalized by insulin secretion and tissue sensitivity to insulin [1]. With Type 2 diabetes, the mechanisms become faulty; the pancreatic beta-cell, which releases insulin, becomes impaired and tissues develop insulin resistance[1][2]. This pathology has a genetic link, although it is somewhat unclear[1].

Risk factors for developing Type 2 diabetes include:

- Overweight or high BMI[3]

- Background of African-Caribbean, Black African, Chinese, or South-Asian, and over 25 years old, or other ethnic background over 40 years old[3]

- High blood pressure, stroke, or heart attack[3]

- Family members have or had diabetes[3]

- History of polycystic ovaries, gestational diabetes, or given birth to baby >10 lbs[3]

- Large waist (men = > 37 inches; women = > 31.5 inches)[3]

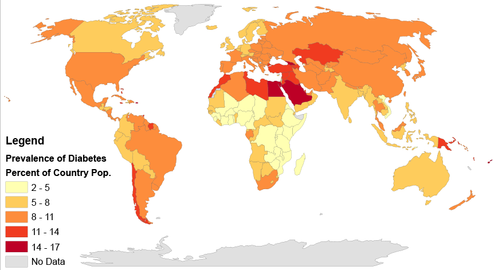

Prevalence[edit | edit source]

According to the International Diabetes Federation (2014), 8.3% of the population or 387 million people are living with diabetes worldwide.[4] Diabetes prevalence increases with age across all regions worldwide and income groups.[5] This number is expected to increase by 205 million by the year 2035.[4] Diabetes is most prevalent in people aged 60-79 years, with 18.6%, though those aged 40-59 have the highest number (184 million) of people living with diabetes.[5] Socio-economic status plays a role in diabetes prevalence. The majority of diabetes incidence (74%) occurs in people over 50 years old in high-income countries, but the majority (59%) occurs in people under 50 years old in low- and middle-income countries.[5] According to the World Health Organization (WHO; 2015), 90% of people with diabetes have type 2.[6] Additionally, there has been an increased prevalence of type 2 diabetes in children and adolescence.[7]

When diabetes strikes during childhood, it is routinely assumed to be type 1, or juvenile-onset diabetes. However, in the last 2 decades, type 2 diabetes has been reported among U.S. children and adolescents with increasing frequency.[8]The true prevalence is difficult to quantify because of the significant difference in occurrence with age, race, and, to a lesser degree, sex. [9]

- Ages 20 years or older: 11.3 percent, of all people in this age group

- Ages 65 years or older: 26.9 percent, of all people in this age group

- Men: 11.8 percent, of all men ages 20 years or older

- Women: 10.8 percent, of all women ages 20 years or older

- Non-Hispanic whites: 10.2 percent, of all non-Hispanic whites ages 20 years or older

- Non-Hispanic blacks: 18.7 percent, of all non-Hispanic blacks ages 20 years or older

There does appear to be a correlation with type 2 diabetes and socioeconomic status, where the more deprived an area’s population is, the higher the incidence of type 2 diabetes is seen.[10][11] A study by Guariguata et al. (2014) looked at global estimates of diabetes in 2013, revealing 74% of diabetes occurrence in high-income countries happens with individuals over 50 years old, whereas 59% of diabetes occurrence happens with individuals under 50 years old.[5] The results for youth do not appear to be much different. A study by Pettitt et al. (2014) in the United States of America found higher occurrence of Type 2 diabetes for youth <20 years old in American Indians/Alaskan Natives (0.63/1000 people), Blacks (0.56/1000 people), and Hispanic (0.40/1000 people) in comparison to Asian/Pacific Islanders (0.19/1000 people) and Non-Hispanic whites (0.09/1000 people).[11]

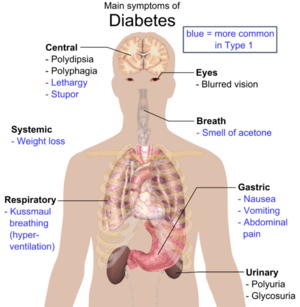

Symptoms[edit | edit source]

There are a number of symptoms associated with type 2 diabetes, mainly due to the fact that either some or all of the glucose stays in your bloodstream and is not utilised as fuel for energy. The main symptoms that present themselves are;

- An increased thirst

- Passing more urine than normal

- Constantly feeling lethargic

- Sudden unexplained weight loss

- Itching around the genitalia (or frequent occurrences of thrush)

- Slow healing cuts and wounds

- Blurred vision due to the lens of the eye becoming dry.[12]

In type 2 diabetes hyperglycemia is when the blood glucose levels become very high and it can cause the main symptoms displayed in diabetes, extreme thirst and excessive and frequent urination[12].

Pulmonary Function[edit | edit source]

In the past there has been large focus on the effects of Type 2 diabetes on the cardiovascular system, nephropathy, neuropathy and retinopathy. However the effects it has on the pulmonary system has been overall, weakly researched.[13] It was shown by Aparna (2013), in line with the findings of Lange et al (1989), that the pulmonary capacity of those with type 2 Diabetes is significantly reduced.[13][14] Due to the changes in collagen and elastin through type 2 Diabetes, this is likely partially the cause of pulmonary complications in those patients.[13] It is suggested that detecting pulmonary complications through spirometry readings may in fact precede the diagnosis of type 2 Diabetes.[15] Given the research at hand at this time it would be prudent to establish spirometry tests to assess the magnitude of the lung function available. It is shown that spirometry tests to establish pulmonary function may be one of the easiest and earliest measurable factors in those with diabetes.

Associated Co-morbidities[edit | edit source]

Diabetes is often detected when an associated co-morbidity is seen in the patient, because these are often the first symptoms the patient will notice. Diabetes may present with any of the following:

- Obesity

- Cardiovascular Disease

- Reduced Pulmonary function

- Neuropathies

- Retinopathy

- Skin wounds or infections

- Stroke

- Hyperglycemia [16]

The following disorders can also be seen in adults with type 2 diabetes, but are the ones most commonly seen in adolescents who have the disorder.

- Hypertension

- Dyslipidemia

- Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD)[17]

Diagnostic Tests[edit | edit source]

There are two main types of tests for diabetes diagnosis. A test known as A1C is considered by some to be the gold standard for diabetes diagnosis. According to the National Diabetes Information Clearinghouse (NDIC; 2014), the A1C provides information to determine blood glucose levels over the past three months.[18] Having such data over months provides clear advantages over fasting blood glucose measurements. For example, A1C does not require patient fasting, A1C markers offer stronger correlates to diabetes, and A1C is a good predictor for cardiovascular events, whereas fasting blood glucose levels are not.[19] However, fasting blood glucose tests do offer practical benefit.[19] For example, glucose testing is readily added to laboratory analysis tests that already require fasting.[19] Additionally, A1C is not available in lots of areas and is more expensive than fasting blood glucose tests.[19] Cost and ease of administration must be considered given diabetes increased prevalence within low- and middle-income countries.

The A1C blood test indicates your average blood sugar level for the past two to three months. It works by measuring the percentage of blood sugar attached to hemoglobin, the oxygen-carrying protein in red blood cells. The higher your blood sugar levels, the more hemoglobin you'll have with sugar attached. The results of this test are[19]:

- Normal: Less than 5.7%

- Pre-diabetes: 5.7% - 6.4%

- Diabetes: 6.5% or higher

If the A1C test isn't available, or if you have certain conditions that can make the A1C test inaccurate — such as if you're pregnant or have an uncommon form of haemoglobin (known as a haemoglobin variant) — your doctor may use the following tests to diagnose diabetes:

- Random blood sugar test. A blood sample will be taken at a random time. Blood sugar values are expressed in milligrams per deciliter (mg/dL) or millimoles per liter (mmol/L). Regardless of when you last ate, a random blood sugar level of 200 mg/dL (11.1 mmol/L) or higher suggests diabetes, especially when coupled with any of the signs and symptoms of diabetes, such as frequent urination and extreme thirst. A level between 140 mg/dL (7.8 mmol/L) and 199 mg/dL (11.0 mmol/L) is considered pre-diabetes, which puts you at greater risk of developing diabetes. A blood sugar level less than 140 mg/dL (7.8 mmol/L) is normal.

- Fasting blood sugar test. A blood sample will be taken after a fast, defined as no caloric intake for at least 8 hours. A fasting blood sugar level less than 100 mg/dL (5.6 mmol/L) is normal. A fasting blood sugar level from 100 to 125 mg/dL (5.6 to 6.9 mmol/L) is considered pre-diabetes. If it's 126 mg/dL (7 mmol/L) or higher on two separate tests, you have diabetes mellitus. From 100 mg/dL (5.6 mmol/L) to 125 mg/dL (6.9 mmol/L) is considered pre-diabetes, which puts you at greater risk of developing diabetes.

- Oral glucose tolerance test. For this test, you fast overnight, and the fasting blood sugar level is measured. Then you drink a sugary liquid, and blood sugar levels are tested periodically for the next several hours. A blood sugar level less than 140 mg/dL (7.8 mmol/L) is normal. A reading of more than 200 mg/dL (11.1 mmol/L) after two hours indicates diabetes. A reading between 140 and 199 mg/dL (7.8 mmol/L and 11.0 mmol/L) indicates prediabetes.

If you do not currently have Diabetes, but are at risk, or simply concerned, diabetes screening is recommended for:

- Overweight children who have other risk factors for diabetes, starting at age 10 and repeated every two years.

- Overweight adults (BMI greater than 25) who have other risk factors

- Adults over age 45 every 3 years

Systemic Involvement[edit | edit source]

Diabetes is a serious condition if it is not closely monitored and controlled. If a person's blood sugar becomes too high for an extended period of time, it can cause damage to multiple areas of the body;

- The Eyes: Diabetes can cause damage to the blood vessels within the eyes which can cause cataracts, glaucoma, retinopathy and in severe cases even blindness. A diabetic retinopathy can be managed by laser eye treatment, however this will only preserve the sight you have and not return sight that has been lost. It is important to have regular check ups with an optician to monitor any changes to the eye.

- The Nervous System: Too much glucose in the bloodstream can cause damage to the small blood vessels within nerves. This can cause numbness, tingling, and pain especially in the hands and feet. One may lose sensation in these areas, which can lead to sores, and possibly amputation. If it affects the nerves in the digestive system then the patient may suffer from nausea and vomiting, diarrhoea or constipation.

- The Heart: Those with type 2 diabetes are up to five times more likely to develop some form of heart disease. extended periods of time with badly controlled glucose levels can cause atherosclerosis, a narrowing of the vessels, leading to a poor blood supply to the heart, ultimately causing angina. If the blood vessel is blocked it will cause either a heart attack or stroke, dependant on where the vessel leads to.

- The Kidneys: High blood sugar levels make it much harder on your kidneys to filter blood, and the kidneys will eventually become overworked. This will cause the kidneys to become blocked and leaky, reducing their efficiency. In severe cases it can eventually cause kidney failure. [20]

Management[edit | edit source]

Medications[edit | edit source]

At this moment in time there is no current cure for diabetes, there is only treatment available to help keep the blood glucose levels as normal as they possibly could be in order to help prevent further complication later on in life.[21] Medications will not be the first choice for your GP to refer you onto, first of all they will recommend a change in diet, and increase in physical activity and a decrease in weight to help manage the diabetes without the need for drugs.[21]

Given that type 2 diabetes will usually get worse over time, those with type 2 diabetes will eventually be placed on some kind of medication to help with the management of their diabetes. There are a number of different medications that can be used to control blood glucose levels but the most commonly known is Metformin.

Metformin [edit | edit source]

Metformin works by affecting the amount of glucose your liver can release into your bloodstream, as well as making the body's cells more responsive to insulin. It does this by activating the energy-regulating enzyme AMP-Kinase in the liver and the muscles.[22] Metformin is given to those who already have developed type 2 diabetes and to those who are at risk of developing type 2 diabetes.[21] Metformin can cause side effects though, with it being known to cause diarrhoea and hypoglycaemia. [21][22]

Sulphonylureas [edit | edit source]

Sulphonylureas increase the endogenous release of insulin from the pancreas. [21] There are multiple versions of Sulphonylureas;

- Glibenclamide

- Gliclazide

- Glimepiride

- Glipizide

- Gliquidone

These medicines are prescribed when the patient is unable to take Metformins or if they are not overweight. However it may be prescribed in conjunction with Metformin, if Metformin is not lowering blood glucose levels on its own.[21] Sulphonylureas will increase the patient's risk of developing hypoglycaemia, as well as some other side effects such as diarrhoea, weight gain and nausea. [21]

Thiazolidinediones (Glitazones)[edit | edit source]

Glitazones work by essentially making the body's cells more sensitive to insulin, meaning that more glucose is taken from the bloodstream. It does so by activating nuclear receptors and promoting esterification and the storage of free fatty acids in the subcutaneous adipose tissue. [22]There is only one of these medications currently being prescribed in the UK, Pioglitazone, as Rosiglitazone was withdrawn due to its side effects of heart attacks and heart failure. [21] Glitazones are usually taken in combination with either metformin and/or sulphonylureas. These drugs will usually cause weight gain and swelling of the ankles (oedema) as side effects. [21]

Gliptins (DPP-4 inhibitors)[edit | edit source]

These work by stopping the breakdown of the hormone GLP-1, the hormone which helps the body produce insulin in a response to high levels of glucose in the blood, but is quickly broken down. In preventing this breakdown, the gliptins prevent high levels of glucose in the blood, without causing moments of hypoglycaemia. [21][22]

GLP-1 Agonists [edit | edit source]

An example of a GLP-1 Agonist is Exenatide. This is an injectable drug which performs a similar action to that of the natural hormone, GLP-1. It is injected twice daily in order to help boost the insulin production when there are high levels of blood glucose, reducing blood glucose, but without the risk of going into a hypoglycemic attack.[21] A GLP-1 Agonist is normally used as a third line of defence when both metformin or sulphonylureas are working for the patient. [22]

Diabetic Foot Care[edit | edit source]

Damage to the nervous system is a systemic problem that may occur with diabetes. Foot neuropathy is common in patients with diabetes, therefore diabetic foot care is an important aspect of the medical management of diabetic patients. Numbness and tingling of the feet can cause foot injury and wounds to go unnoticed, which may lead to breakdown and infectious wounds of the skin. Damage to the nervous system also impairs sweat secretion and oil production of the foot. If proper lubrication of the foot does not occur, this leads to abnormal pressure on the skin, bones, and joints during walking and will also result in skin breakdown and sores on the foot.

Diabetic patients must be aware how to prevent foot problems before they happen. Treatment for diabetic foot problems have recently improved, but prevention remains the best way to prevent complications.

- Diabetic patients need to learn how to properly examine their own feet and be able to recognize early signs and symptoms of diabetic foot problems.

- Diabetics should be educated on proper footwear. [24]

Footwear and orthotics play a crucial role in foot care. Plastazote foam is the best material for protecting a diabetic foot. This material is made to conform to heat and pressure while also providing comfort and protection. Diabetic footwear should also include a high, wide toe box to increase space and minimize pressure, removable insoles to insert orthotics, rocker soles to decrease pressure, and heel counters to provide support and stability. [25]

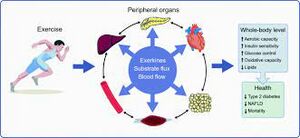

Exercise[edit | edit source]

- The body can use insulin better by performing any exercise, which causes a reduction in the amount released by the pancreas as muscle contractions help increase glucose absorption[26].

- Exercise contributes to the effect of insulin for anyone who injects it, most likely lowering blood sugar to dangerously low levels[27].

- For diabetic patients, it's important to plan their exercise cautiously and monitor it carefully to avoid serious complications. In addition, careful monitoring of blood glucose levels before, during, and after strenuous exercise is also necessary; safe levels are determined according to the overall patient's condition but usually come between 100 mg/dl and 250 mg/dl; between 250 mg/dl and 300 mg/dl is regarded as a "caution zone."[28]

- There may be an insulin deficiency if blood glucose level is between 250 and 300 mg/dl and the body is breaking down fat for energy, so exercise sessions should be postponed until urine is tested, which will confirm or exclude that by finding ketones or not.

- High-intensity exercise should be avoided for patients with active retinopathy and nephropathy because such training may damage the retinas and kidneys by increasing blood pressure.[29]

- Read Physical activity and diabetes for more information.

Diet[edit | edit source]

High blood sugar needs to be controlled in diabetics and some basic diabetic eating habits may include:

- Limit foods that are high in sugar

- Eat smaller portion sizes

- Be conscious of carbohydrates one eats

- Eat whole grains, fruits, and vegetables everyday

- Limit fat intake

- Limit use of alcohol

- Limit salt intake[30]

Physical Therapy Management[edit | edit source]

The National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) team are releasing four new guidances relating to diabetes management by August 2015.[31]

Type 2 diabetes often occurs in children and adults who are overweight and live a sedentary lifestyle. It is shown that approximately 80% of patients receiving physical therapy services have diabetes, pre diabetes, or at least one risk factor for type 2 diabetes.[32]Physical therapist can utilize exercise programs as an effective treatment for patients with type 2 diabetes and it has been proven that regular physical activity is crucial to in sustaining low blood sugar levels and improving insulin sensitivity. An exercise program for patients with type 2 diabetes should included combined endurance, aerobic, and resistance training.[32][33]

- Aerobic Exercise: Patients should perform an aerobic exercise program 3-5 days per week and for 150 minutes per week at mid to moderate intensity (RPE 10-12/20). A resistance training program should also be performed for all major muscle groups 2-3 days per week. If patients have peripheral neuropathy, a common condition in type 2 diabetic patients, non weight bearing activities should be performed.[32]

2. Strength Training: In general, most people can tolerate 30-50% of 1 rep maximum for a workload during exercise training.

- Number of sets and repetitions. 1-2 sets per exercise is a good starting point for clients. Repetitions can be established in the same manner as you would for an individual without diabetes. Base your prescription on the client’s individual goals and their exercise tolerance. In general, use lower repetitions/higher resistance for strength and higher repetitions/lower resistance for endurance.

- Rest time between sets. Using 30-60 seconds for the rest period is appropriate in most situations. With greater intensity bouts a slightly longer (up to 2 minutes) rest period may be necessary.[34]

- Frequency of strength training. Having the client strength train at least two days per week is appropriate in order to see beneficial results from the type of exercise, as shown in the study by Eriksson and colleagues.[35]

3. Aerobic and resistance training as shown to decrease A1C levels by 0.8 or 3% in 12 weeks.[10] Patients should avoid skipping exercise for more than 2 days at a time in order to prevent deterioration of glucose tolerance and insulin sensitivity.

Blood Sugar Monitoring.

- While exercising with patients that have type 2 diabetes it is important to also check their blood sugar before exerciseDuring exercise, low blood sugar is sometimes a concern. If client is planning a long workout, check their blood sugar every 30 minutes — especially if their trying a new activity or increasing the intensity or duration of workout. Checking every half-hour or so lets the client know if blood sugar level is stable, rising or falling, and whether it's safe to keep exercisingt[36]. This may be difficult if participating in outdoor activities or sports. But, this precaution is necessary until you know how your blood sugar responds to changes in your exercise habits.

- save levels are individually ruled but fall between 250mg/dl and

Stop exercising if:

- Your blood sugar is 70 mg/dL (3.9 mmol/L) or lower

- You feel shaky, weak or confused[36]

If a patient's blood sugar is <70 mg/dL before exercise, give them 15 grams of a carbohydrate snack, recheck in 15 minutes, and if above 70 mg/dL continue with exercise. If a patient's blood sugar is between 70-150 mg/dL, give them 15 grams of a carbohydrate snack every hour of performed moderate intensity exercise. If blood sugar is between 100-300 mg/dL, it is safe to exercise. If blood sugar is >300 mg/dL and the patient is on oral medications, do 15 minutes of exercise and check again. If blood sugar rises, stop exercise, if it drops, continue. If blood sugar is >300 mg/dL and the patient is on insulin, it is important to check for ketones. If ketones are positive, stop exercise.[32]

References[edit | edit source]

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 1.5 1.6 1.7 1.8 Ozougwu J, Obimba K, Belonwu C, Unakalamba C. The pathogenesis and pathophysiology of type 1 and type 2 diabetes mellitus. Journ or Phys and Pathophys. 2013;4:46-57

- ↑ National Diabetes Information Clearinghouse (NDIC). Insulin resistance and prediabetes. Available from: http://diabetes.niddk.nih.gov/dm/pubs/insulinresistance/#resistance (accessed 5 May 2015).

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 3.4 3.5 Diabetes UK. Diabetes risk factors. Available from: https://www.diabetes.org.uk/Guide-to-diabetes/What-is-diabetes/Know-your-risk-of-Type-2-diabetes/Diabetes-risk-factors/ (accessed 5 May 2015).

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 International Diabetes Federation (IDF). Diabetes: facts and figures. Available from: https://www.idf.org/worlddiabetesday/toolkit/gp/facts-figures (accessed 5 May 2015).

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 5.3 Guariguata L, Whiting DR, Hambleton I, Beagley J, Linnenkamp U, Shaw JE. Global estimates of diabetes prevalence for 2013 and projections for 2035. Diabetes Research and Clinical Practice. 2014;103:137-49.

- ↑ World Health Organization (WHO). Diabetes programme. Available from: http://www.who.int/diabetes/en/ (accessed 5 May 2015).

- ↑ World Health Organization. Diabetes: fact sheet, 2018. Available from: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/diabetes (accessed 2 October 2019).

- ↑ Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Children and Diabetes. Atlanta, 2011. Available From: http://www.cdc.gov/diabetes/projects/cda2.htm [2 April 2012].

- ↑ National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases. National Diabetes Statistics, 2017. Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/diabetes/pdfs/data/statistics/national-diabetes-statistics-report.pdf [Accessed 2 October 2019]

- ↑ Connolly V, Unwin N, Sherriff P, Bilous R, Kelly W. Diabetes prevalence and socioeconomic status: a population based study showing increased prevalence of type 2 diabetes mellitus in deprived areas. Journal of Epidemiol Coomunity Health. 2000; 54: 173–177.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 Pettitt DJ, Talton J, Dabelea D, Divers J, Imperatore G, Lawrence JM, et al. Prevalence of diabetes in U.S. youth in 2009: the search for diabetes in youth study. Diabetes Care. 2014; 37:402-08.

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 NHS Choices. Type 2 Diabetes - Symptoms. Available from: https://www.nhs.uk/conditions/type-2-diabetes/symptoms/ [Accessed 2 October 2019]

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 13.2 Aparna A. Pulmonary function tests in type 2 diabetics and non-diabetic people - a comparative study. Journal of Clinical and Diagnostic Research 2013;7(9):1606-1608

- ↑ Lange P, Groth S, Kastrup J, Mortensen J, Appleyard M, Nyboe J et al. Diabetes mellitus, plasma glucose and lung function in a cross sectional population study. Eur Resp J. 1989;2(1):14-19

- ↑ Kaminsky DA. Spirometry and diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2004;27:837-38

- ↑ Okosun I, Chandra KM, Choi S, Christman J, Dever GE, Prewitt TE. Hypertension and Type 2 Diabetes Comorbidity in Adults in the United States: Risk of Overall and Regional Adiposity. Obesity Research. 2001; 9: 1–9.

- ↑ Laffel L, Svoren B. Comorbidities and complications of type 2 diabetes mellitus in children and adolescents. Wolters Kluwer Health. 2007; 369(9575):1823.

- ↑ National Diabetes Information Clearinghouse. The A1C test and diabetes. Available from: http://diabetes.niddk.nih.gov/dm/pubs/A1CTest/#1 (accessed 5 May 2015).

- ↑ 19.0 19.1 19.2 19.3 19.4 Bonora E, Tuomilehto J. The pros and cons of diagnosing diabetes with A1C. Diabetes Care. 2011;34:S184-90.

- ↑ Livestrong. Which Systems Of The Body Are Affected by Diabetes [1]. Demand Media, Inc. 2011. Available from http://livestrong.com/ (accessed 3 April 2012)

- ↑ 21.00 21.01 21.02 21.03 21.04 21.05 21.06 21.07 21.08 21.09 21.10 NHS Choices. Type-2 diabetes - treatment. Available from: www.nhs.uk/conditions/diabetes-type2/pages/treatment.aspx (accessed 26 may 2015)

- ↑ 22.0 22.1 22.2 22.3 22.4 Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network. Management of Diabetes: A national clinical guideline. 2014. Available from: https://services.nhslothian.scot/DiabetesService/InformationHealthProfessionals/Documents/sign116.pdf (accessed 3 October, 2019)

- ↑ healthery. What is Diabetes Mellitus? (Symptoms, Causes, Treatment, Prevention). Available from: https://https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=9pSWLJ0s_e8 (last accessed 3.10.2019)

- ↑ Emedicinehealth. Diabetic Foot Care. Available From: https://www.emedicinehealth.com/diabetic_foot_care/article_em.htm (accessed 3 October 2019)

- ↑ Foot.com. The Diabetic Foot [2]. Aetrex Worldwide, Inc. 2010. Available From: http://www.foot.com/ (accessed 3 April 2012)

- ↑ Bird SR, Hawley JA. Update on the effects of physical activity on insulin sensitivity in humans. BMJ open sport & exercise medicine. 2017 Mar 1;2(1):e000143.

- ↑ Colberg SR, Sigal RJ, Fernhall B, Regensteiner JG, Blissmer BJ, Rubin RR, Chasan-Taber L, Albright AL, Braun B. Exercise and type 2 diabetes: the American College of Sports Medicine and the American Diabetes Association: joint position statement. Diabetes care. 2010 Dec 1;33(12):e147-67.

- ↑ Pokhrel A, Silvanus V, Pokhrel BR, Baral B, Khanal M, Gyawali P, Pokhrel L, Regmi D. Accuracy of glucose meter among adults in a semi-urban area in Kathmandu, Nepal. JNMA: Journal of the Nepal Medical Association. 2019 Apr;57(216):104.

- ↑ Jenkins AJ, Joglekar MV, Hardikar AA, Keech AC, O'Neal DN, Januszewski AS. Biomarkers in diabetic retinopathy. The review of diabetic studies: RDS. 2015;12(1-2):159.

- ↑ MedlinePlus. Diabetic Diet. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Available From: https://medlineplus.gov/diabeticdiet.html (accessed 3 April 2012).

- ↑ NICE. Type 2 diabetes in Adult: Management. Available from: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/indevelopment/gid-cgwave0612 (accessed 3 October 2019).

- ↑ 32.0 32.1 32.2 32.3 American College of Sports Medicine. ACSM's Guidelines for Exercise Testing and Prescription. 8th ed. Philadelphia:Lippincott Williams and Wilkins; 2010.

- ↑ Ghodrati N, Haghighi AH, Kakhak SA, Abbasian S, Goldfield GS. Effect of combined exercise training on physical and cognitive function in women with type 2 diabetes. Canadian Journal of Diabetes. 2023 Mar 1;47(2):162-70.

- ↑ UNM education Training Clients With Diabetes Jeffrey Janot, M.S. and Len Kravitz, Ph.D. https://www.unm.edu/~lkravitz/Article%20folder/diabetes.html (Accessed 14.7.2021)

- ↑ International Journal of Sport Med 1997 May;18(4):242-6 Resistance training in the treatment of non-insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus J Eriksson /pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/9231838/#affiliation-1|1]], S Taimela, K Eriksson, S Parviainen, J Peltonen, U Kujala. . 1997 May;18(4):242-6. Available:https:/pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/9231838/(accessed 15.7.2021)

- ↑ 36.0 36.1 Mayo Clinic Diabetes and Exercise Available: https://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/diabetes/in-depth/diabetes-and-exercise/art-20045697 (accessed 13.7.2021)