Heart Failure

Original Editors - Students from Glasgow Caledonian University's Cardiorespiratory Therapeutics Project.

Top Contributors - Lucinda hampton, Jayati Mehta, Vidya Acharya, Doireann Church, Kim Jackson, Caoimhe Mackey, Areeba Raja, Admin, WikiSysop, Aminat Abolade, 127.0.0.1, Evan Thomas, Michelle Lee and Karen Wilson

Introduction[edit | edit source]

Heart failure is a syndrome of cardiac ventricular dysfunction, where the heart is unable to pump sufficiently to meet the body's blood flow requirements.

- The symptoms come from an inadequate cardiac output, failing to keep up with the metabolic demands of the body.

- It is a leading cause of cardiovascular morbidity and mortality worldwide despite the advances in therapies and prevention.

- It can result from disorders of the pericardium, myocardium, endocardium, heart valves, great vessels, or some metabolic abnormalities.[1]

Heart failure is a major public health concern in countries worldwide. The increasing prevalence of heart failure in the population is most likely secondary to the aging of the population, increased risk factors, better outcomes for acute coronary syndrome survivors, and a reduction in mortality from other chronic conditions[2]. It is estimated that globally more than 25 million people are affected by HF.[3]

Epidemiology[edit | edit source]

Heart failure is a significant public health problem with a prevalence of over 5.8 to 6.5 million in the U.S. and around 26 million worldwide[4].

Multiple conditions can cause HF, including systemic diseases, a wide range of cardiac conditions, and some hereditary defects.

- Etiologies of HF vary between high-income and developing countries, and patients may have mixed etiologies.

- Coronary artery disease and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) are the most common underlying causes of HF in high-income regions.

- Conversely, hypertensive heart disease, rheumatic heart disease, cardiomyopathy, and myocarditis are the primary conditions for HF in low-income regions, according to a systemic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study.

- More than two-thirds of all cases of HF are attributable to ischemic heart disease, COPD, hypertensive heart disease, and rheumatic heart disease.[1]

Aetiology[edit | edit source]

There are multiple risk factors for heart failure, including older age (65 years or over), being male, having a family history of the condition, or having certain underlying conditions, particularly myocardial infarction , cardiac valve insufficiency (leaking) or stenosis (narrowing), and diabetes. Certain lifestyle factors—such as tobacco smoking, alcohol consumption, physical inactivity, and a diet that predisposes individuals to high cholesterol and high blood pressure—also raise the risk of developing heart failure[3]

Clinical presentation[edit | edit source]

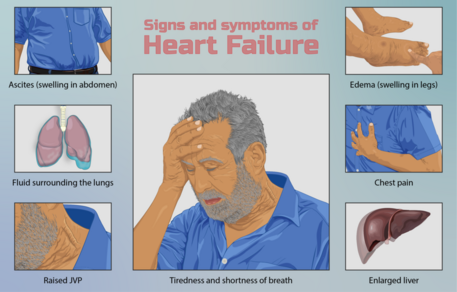

Although it is useful to divide the signs and symptoms of heart failure according to the degree of left or right ventricular dysfunction, the heart is an integrated pump, and patients commonly present with both sets of signs and symptoms.

Left ventricular failure: Patients usually report fatigue, dyspnea on exertion, and if severe, at rest. Orthopnea, paroxysmal nocturnal dyspnea and Cheyne-Stokes respiration can also be a feature.

- On examination tachypnea, dyspnea, tachycardia, hypotension and cyanosis may be observed. Palpation may reveal a laterally displaced apex beat while cardiac auscultation may elicit murmurs such as aortic stenosis or mitral regurgitation. Features of pulmonary edema eg inspiratory bibasal crackles not cleared on coughing, diminished breath sounds and dullness to percussion, may also be noted.

Right ventricular failure: Symptoms include ankle swelling, fatigue, abdominal bloating/discomfort and nocturia.

- Evidence of right ventricular failure can manifest as peripheral edema (if severe extending to thighs and sacrum), ascites, hepatomegaly, elevated jugular venous pressure (JVP). JVP can be further accentuated by hepatojugular reflux. Cardiac murmurs may also be heard, commonly tricuspid regurgitation.

Clinical severity varies significantly and usually classified according to the New York Heart Association, which is graded according to how much physical activity is decreased[5].

Pathology[edit | edit source]

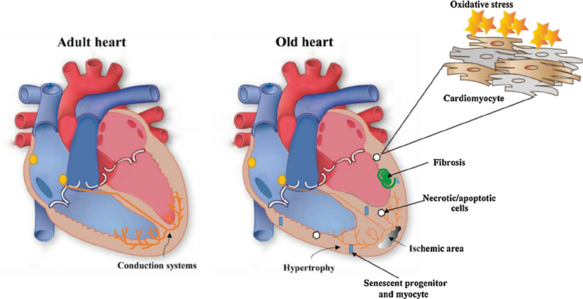

Myocardial damage due to myocardial infarcts, cardiomyopathy and myocarditis can cause or aggravate heart failure.

Additionally, valvular disease such as aortic stenosis or mitral regurgitation may result in heart failure as well.

Further causes include conduction defects, cardiac arrhythmia and infiltrative/matrix disorders.

Systemic factors that may contribute or exacerbate heart failure include anemia, hyperthyroidism or hypertension[5].

See also Cardiovascular Considerations in the Older Patient

Management[edit | edit source]

Prognosis is usually poor unless the underlying cause is reversed. As a result, patients generally gradually deteriorate with episodes of acute decompensation and ultimately death.

In addition to treating the underlying cause of heart failure, management is directed at dietary and lifestyle changes, medications including ACE inhibitors or beta blockers and if appropriate, implantable cardioverter-defibrillator (ICD) or cardiac resynchronisation therapy (CRT).[5] Diuretics are prescribed to remove excess fluid. Digoxin and digitoxin are commonly prescribed to increase the strength of heart contraction[3].

Patients are also advised to limit their intake of salt and fluids, avoid alcohol and nicotine, optimize their body weight, and engage in aerobic exercise as much as possible. Much can be done to prevent and treat heart failure, but ultimately the prognosis depends on the underlying disease causing the difficulty as well as the severity of the condition at the time of presentation.

See also Pharmacological Management of Heart Failure

Physiotherapy[edit | edit source]

Physiotherapy is important in the management of heart failure. The cornerstone of physiotherapy management is cardiac rehabilitation. In patients undergoing heart surgery, physiotherapy can also help with recovery after surgery.

Up until the late 1980s, exercise was considered unsafe for the patient with HF. It was unclear whether any benefit could be gained from rehabilitation, and concern also existed regarding patient safety, with the belief that additional myocardial stress would cause further harm. Since this time, considerable research has been completed and the evidence resoundingly suggests that exercise for this patient group is not only safe but also provides substantial physiological and psychological benefits. As such, exercise is now considered an integral component of the non pharmacological management of these patients

Aims of effective treatment for heart failure[edit | edit source]

- Strengthen the heart

- Improve symptoms

- Reduce the risk of a flare-up or worsening of symptoms

- Improve Quality of Life

- Offer longevity

Recent research findings[edit | edit source]

- Systematic review and meta-analysis show a significant effect of aerobic and resistance training on peak oxygen consumption, muscle strength, and health-related quality of life in patients with heart failure with a reduced left ventricular ejection fraction[6]

- A study published in the Journal of Cardiopulmonary Rehabilitation and Prevention 2020, comparing the effects of β-blockers and non-β-blockers on Heart Rate (HR) and Oxygen Uptake (VO2) during exercise and recovery in older patients with heart failure with a preserved ejection fraction (HFpEF) demonstrated no significant differences in values (HRpeak, HRresv, HRrecov, or VO2) between both the groups, along with significant correlation between HRresv and VO2peak, suggesting the efficacy of these measures in prognostic and functional assessment and clinical applications, including the prescription of exercise, in elderly HFpEF patients[7].

- Studies show a contrasting effect of aerobic training and resistance training on some echocardiographic parameters in patients with heart failure with reduced ejection fraction. While aerobic training was associated with evidence of worsening myocardial diastolic function, this was not apparent after resistance training. Further studies are indicated to investigate the long-term clinical significance of these adaptations[8].

- А single-blind, prospective randomized controlled trial suggests: modified group-based High-intensity aerobic interval training (HIAIT) intervention showed more considerable improvement as compared to moderate-intensity continuous training (MICT) in the rehabilitation of patients with chronic heart failure (CHF). Physical and rehabilitation medicine (PRM) physicians should apply Group based Cardiac intervention in routine cardiac rehabilitation (CR) practice[9].

- An article published online (March 2020) suggests positive outcomes with the High-intensity interval training (HIIT) for patients with heart failure along with preserved ejection fraction[10].

- A study assessing patients carrying out 5-months cardiac rehabilitation CR showed a lower rate of clinical events with higher maximal inspiratory pressure, suggesting that the changes in respiratory muscle strength independently predicted the occurrence of clinical manifestations in patients with Heart Failure HF[11].

- The results of a cross-sectional study in Spain by Raul Juarez-Vela et al. show that Heart Failure patients depend on others' care, especially for moving, dressing, personal hygiene, participating in daily and recreational activities, suggesting a weaker relationship between care dependency and the patients' physical deterioration[12].

Multidisciplinary team members[edit | edit source]

The other members of the MDT are vast but include

- Surgeons and consultants - They operate if needed. Numerous operations are available and may be suitable for certain patients. For example, Heart Valve Surgery, Angioplasty or Bypass, Left Ventricular Assist Devices, Cardiac Inplant Electronic Devices, Heart Transplant. However, this is individual and would need to be discussed with the consultant in charge of the case.

- Nutritionists - They work out a diet plan to suit the individual needs of the patient. As diet is a risk factor for CHD this is an extremely important member of the MDT for further prevention.

- Counselor - As Heart failure is normally a lifelong condition the patient may have difficulty coming to terms with the impact this will have on their life. A counsellor will be available for sessions on coping with the disease.

- Personal Trainer- As with a Physiotherapist will help to provide a more balanced lifestyle and improve fitness levels. This is something that will not only give the patient goals to work towards but also important social interaction with someone who is seen as less of a medical figure and therefore adds more normality to the individuals day to day life.

- Family and Friends- This support network is an extremely important factor contributing to recover of a patient and should not be overlooked.

The list of people involved in this team is huge and is not exhaustive in this piece, however, Pharmacists, Social Groups, GP’s, Nurses and Podiatrists are all members of this MDT. Recovery cannot occur without input and communication from every member of the team.

Prevention[edit | edit source]

There are many factors that increase the risk of developing heart failure. And with some lifestyle changes and sometimes drug intervention this risk could be dramatically reduced. Hypertension and smoking are major risks for heart failure.

- Stop smoking. Quitting smoking is noted as the single best way to reduce risk of heart failure. Smoking has many physiological effects forcing the heart to walk harder.

- Reduce blood pressure. High blood pressure increases the work demand put on the heart to transport blood around the body, this increased work causes a hypertrophic reaction of the heart muscle, eventually leading to a weakened or stiff heart.

- Reduce Cholesterol Level. High levels of cholesterol can cause furring and narrowing of the arteries termed atherosclerosis and eventually heart failure.

- Lose weight. Being overweight increases demand placed on the heart and increases risk of heart failure and attack.

- Eat a healthy diet. A healthy diet can help reduce your risk of developing coronary heart disease and therefore heart failure.

- Keep active. Regular physical activity will help keep the heart healthy and also maintain a healthy weight.

- Reduce Alcohol intake. Drinking excess of the recommended amount of alcohol per week can increase your blood pressure. Heavy drinking for long periods of time can cause damage to your heart muscle leading directly to heart failure.

- Cut your salt intake. Excessive salt intake increases blood pressure and again, increases stress put on the heart.

Viewing[edit | edit source]

The below is a 12 minute video on HF

Resources[edit | edit source]

Exercise based rehabilitation for heart failure

References[edit | edit source]

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Hajouli S, Ludhwani D. Heart failure and ejection fraction.Available: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK553115/(accessed 19.9.2021)

- ↑ King KC, Goldstein S. Congestive Heart Failure and Pulmonary Edema. StatPearls [Internet]. 2021 Jan 20.Available: https://www.statpearls.com/ArticleLibrary/viewarticle/19880(accessed 2.6.2021)

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 Britannica Heart Failure Available: https://www.britannica.com/science/heart-failure(accessed 1.6.2021)

- ↑ Hajouli S, Ludhwani D. Heart Failure And Ejection Fraction 2020.Available from:https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK553115/ (last accessed 11.8.2020)

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 Radiopedia heart failure Available: https://radiopaedia.org/articles/heart-failure-summary?lang=us(accessed 19.9.2021)

- ↑ Neto MG, Durães AR, Conceição LS, Roever L, Silva CM, Alves IG, Ellingsen Ø, Carvalho VO. Effect of combined aerobic and resistance training on peak oxygen consumption, muscle strength and health-related quality of life in patients with heart failure with reduced left ventricular ejection fraction: a systematic review and meta-analysis. International Journal of Cardiology. 2019 Jun 24.

- ↑ Maldonado-Martín S, Brubaker PH, Ozemek C, Jayo-Montoya JA, Becton JT, Kitzman DW. Impact of β-Blockers on Heart Rate and Oxygen Uptake During Exercise and Recovery in Older Patients With Heart Failure With Preserved Ejection Fraction. Journal of Cardiopulmonary Rehabilitation and Prevention. 2020 Jan 2.

- ↑ Lan NS, Lam K, Naylor LH, Green DJ, Minaee NS, Dias P, Maiorana AJ. The Impact of Distinct Exercise Training Modalities on Echocardiographic Measurements in Patients with Heart Failure with Reduced Ejection Fraction. Journal of the American Society of Echocardiography. 2019 Dec 4.

- ↑ MEDICA EM. Group-based cardiac rehabilitation interventions. A challenge for physical and rehabilitation medicine physicians: a randomized controlled trial. European Journal of Physical and Rehabilitation Medicine. 2020 Jan 23.

- ↑ Paul J Beckers, Andreas B Gevaert High intensity interval training for heart failure with preserved ejection fraction: High hopes for intense exercise European Journal of Preventive Cardiology 0(00) 1–3 The European S Article reuse guidelines: sagepub.com/journals-permissions DOI: 10.1177/2047487320910294 journals.sagepub.com/home/cpr

- ↑ Hamazaki N, Kamiya K, Yamamoto S, Nozaki K, Ichikawa T, Matsuzawa R, Tanaka S, Nakamura T, Yamashita M, Maekawa E, Meguro K. Changes in Respiratory Muscle Strength Following Cardiac Rehabilitation for Prognosis in Patients with Heart Failure. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2020 Apr;9(4):952.

- ↑ Juárez-Vela R, Durante Á, Pellicer-García B, Cardoso-Muñoz A, Criado-Gutiérrez JM, Antón-Solanas I, Gea-Caballero V. Care Dependency in Patients with Heart Failure: A Cross-Sectional Study in Spain. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2020 Jan;17(19):7042.

- ↑ reference