Parkinson's

This article is currently under review and may not be up to date. Please come back soon to see the finished work! (17/04/2024)

Original Editor - Bhanu Ramaswamy as part of the APPDE Project

Top Contributors - Kim Jackson, Admin, Lauren Heydenrych, Rachael Lowe, Laura Ritchie, Lucinda hampton, Wendy Walker, Naomi O'Reilly, Lauren Lopez, Bhanu Ramaswamy, Mariam Hashem, Simisola Ajeyalemi, Vidya Acharya, Nikhil Benhur Abburi, Manisha Shrestha, Jess Bell, Aminat Abolade, Tony Lowe and Scott Buxton

Parkinson's Disease[edit | edit source]

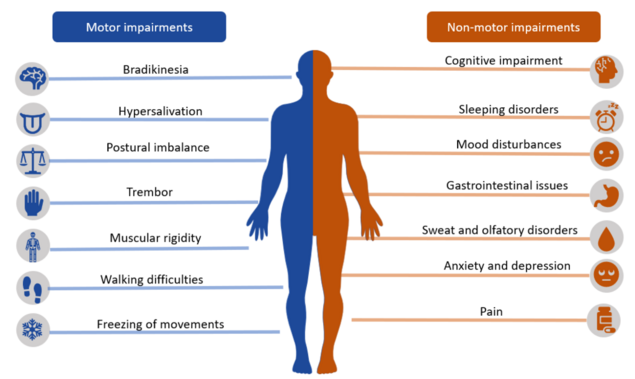

Parkinson's disease (PD) aka Parkinson's is a neurodegenerative disorder (specifically a synucleinopathy). PD mostly presents in later life with generalized slowing of movements bradykinesia) and at least one other symptom of resting tremor or rigidity.[1] " Other associated features are a loss of smell, sleep dysfunction, mood disorders, excess salivation, constipation, and excessive periodic limb movements in sleep (REM behavior disorder)"[1]. It is the second most common neuro-degenerative condition after Alzheimer's and is the fastest growing neurological disorder globally.[2][3]

PD is by far the most common cause of the parkinsonian syndrome, accounting for approximately 80% of cases, the remainder being due to other neurodegenerative diseases e.g. Lewy body dementia.[4]

This 3 minute video gives an overview of PD

Clinically Relevant Anatomy[edit | edit source]

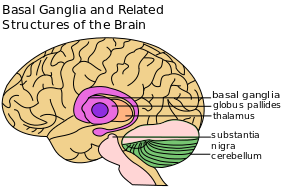

PD is a disorder of the basal ganglia (BG), which is composed of many other nuclei.[6]

The primary nuclear complex of the BG is the striatum. The striatum is composed of the caudate and lenticulate nuclei.[7] It receives afferent projections from almost all areas in the neocortex (the part of the cortex where higher cognitive functioning is thought to originate) as well as nuclei of the thalamus and dopaminergic neurons of the substantia nigra compacta (SNc).[8]

The BG also receives input from pre-central cortical areas, which then terminate in the subthalamic nucleus .[8]

Output projections of the BG are linked to the thalamus and other midbrain nuclei.[8]

Clinical Presentation[edit | edit source]

Parkinson's was described 3000 years ago in Indian and Chinese medicines with mainly plant-based remedies. However, James Parkinson was the first to describe it in Western medicine in his 1817 essay, describing it as the Shaking Palsy.[10]

Pathological Process[edit | edit source]

Initially PD was considered to be primarily a disorder of the basal ganglia, which is composed of many other nuclei. Here the dopaminergic tract was thought to be predominantly affected with characteristic neuronal loss of dopaminergic neurons in the substantia nigra pars compacta.[6][11]Dopamine is a natural substance found in the brain that plays a major role in our brains and bodies by messaging and therefore communicating across various systems. Recent studies however, have also found involvement in other non-dopaminergic neurons in other brain regions including the vagus dorsal motor nucleus, locus coeruleus and raphe nuclei.[11]

Clinical staging of PD[edit | edit source]

The Movement Disorder Society (MDS) has recommended that the following terminology is used in describing the course of PD: This is in particular regard to identification of motor symptoms[12] [11]

- Preclinical - No clinical symptoms. Neurodegenerative synucleinopathy present. phase is... by biomarkers.

- Prodromal - Early symptoms of PD before diagnosis. Normally 15-20 years before onset of motor symptoms.

- Clinical - Diagnosis of PD made, based on presence of motor signs.

Epidemiology[edit | edit source]

PD usually occurs after the age of 50 affecting 1 to 2 people per 1000 at any time. An estimated seven to 10 million people worldwide are living with Parkinson's.[13] The prevalence increases with age to affect 1% of the population above 60 years. Genetics play a part in 5% to 10% of patients and this is seen in young patients. It is more common in men than women, with incidence and prevalence rising with age[1].

Etiology[edit | edit source]

The cause of PD has been linked to:

- Environmental risk factors.[11] This includes:

- Use of pesticides and herbicides.

- Injection of 1-methyl-4-phenyl-1,2,3,6-tetrahydropyridine (MPTP), seen in illicit drug use.

- Exposure to heavy metals, e.g. manganese. For example in welding.

- Increased evidence points to PD as a result of recurrent head trauma. For example in boxing, American football and rugby players. However, this etiology tends to give rise to a different pathology than typical PD development.

- Medications, including calcium channel blockers, NSAIDs, and statins.

- Oxidation and generation of free radicals causing damage to the thalamic nuclei.

- Genetics. The risk of PD in siblings is increased if one member of the family has the disorder. These cases also tend to occur much earlier in life. In PD cases reported, up to 10% confirm a family history of PD.[11]

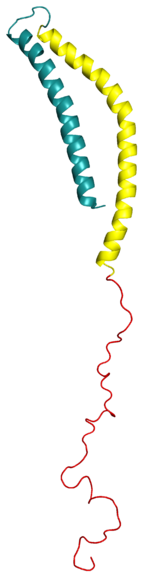

- The altered function of alpha-synuclein may play a role in the etiology of PD. Current research is focused on preventing the propagation and aggregation of alpha-synuclein[1]

Diagnostic Procedures[edit | edit source]

Diagnosis of PD often only occurs late in disease progression and is dependent on clinical motor findings. [14]

In an evaluative review published in 2018, a series of diagnostic biomarkers were highlighted which show promise in the early identification of PD as well as differentiation from other diseases giving rise to parkinsonian syndrome.:[14]

- Clinical signs and symptoms = Motor symptoms of bradykinesia, with associated resting tremor or rigidity or both. These however, present relatively late in the pathological process, where there has been approximately 50% loss of dopeminergic neurons in the substantia nigra.[12]

- Imaging = Ultra-high field 7 T MRI can now detect dopaminergic cell loss in the pars compacta - a hallmark of PD. Radiotracer imaging with single photon emission computed tomography (SPECT), position emission tomography (PET) and transcranial sonography (TCS) can also be used.[12]

- Olfactory dysfunction = Hyposmia. While this is a common feature, often picked up in early PD, it is also a common phenomenon in aging. Nevertheless it is considered a useful preclinical marker of PD in combination with other markers.

- REM behaviour sleep disorder = Parasomnia (disruptive sleep disorders) involving abnormal behaviour caused by loss of the physiological motor inhibition normally present during REM (rapid eye movement) sleep. This can range from sleep talking to violent dream enacting.

- Excessive daytime sleepiness = Inability to keep awake during the daytime and sleep occuring during unintentional or inappropriate times.

- Insomnia = Difficulty in initiating sleep or maintaining sleep or the presence of early awakenings or all. This can be due not only to PD itself, but because of other factors including depression, anxiety, PD drugs and their withdrawal.

- Constipation = Idiopathic constipation is a strong risk factor for PD. Also associated are markers of inflammation, oxidative stress, increased mucosal permeability as well as neurodegnerative and A-synuclein accumulation within the enteric system.

- Depression = While present in 30% of cases prior to PD motor symptoms and showing a marked increase just prior to motor symptom onset, depression cannot be used alone as it has a high prevalence in the general population. Depression can also be misdiagnosed as abulia, a disorder of diminished motivation.

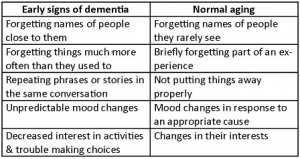

- Cognition = Mild cognitive impairment can be seen in 15-20% of patients diagnosed early with PD.

- Visual dysfunction = Can be a sensitive biomarker. Symptoms can include changes in colour vision, contrast sensitivity and difficulties in complex visual tasks.

- Biological fluids = Different levels of α-synuclein in it's different forms and the ratios of different metabolites in various tissues have been explored. However, results have not been definitive as yet. Other biomarkers looked at include serum urate, epidermal growth factor and apolipoprotien A1.

- Pathology = α-synuclein pathology noted in tissues such as the GI tract. Also considered is intestinal dysbiosis - with an imbalance of bacterial strains associated with pro-inflammation.

- Genetics = Certain genes have been identified as 'high risk' for the development of PD. Furthermore, a family history of PD increases the odds of developing PD by 3-4x.[12]

- Omics = The study of disease networks and molecular pathways aims to identify cellular processes or connections on the molecular level leading to PD.

- Inflammation = Inflammation is seen as having a role to play in PD due to protein misfolding leading to a proinflammatory state. This in turns gives rise to microglial activation and subsequent neurodegeneration.

Outcome Measures[edit | edit source]

Motor impairment can be assessed using:[14]

Unified Parkinson’s disease rating scale (UPDRS) or

The revised version of the Movement Disorder Society (MDSUPDRS).

Interprofessional Management[edit | edit source]

PD is one of the most common motor disorders worldwide. The disorder has no cure and is progressive. PD can present with motor abnormalities and a variety of psychiatric and autonomic problems. Almost every organ is affected by this disorder, and as the disease progresses, management can be difficult. An interprofessional team approach is the best way to manage the disorder[1].

Some non-motor aspects (sleep problems, low mood, constipation, and loss of sense of smell) occur several years prior to observable motor symptoms develop. Physiotherapists are most often involved in the mid-stages of the condition, once balance and mobility become affected, but it can be helpful if they can assess and advise people soon after diagnosis in order to maintain activity and prevent problems.

Besides physicians, nurses, pharmacists, social workers, and physical therapists play a vital role in the daily management of these patients. Parkinson’s creates complexities for health and social staff helping individuals and those affected by it (carers, family members, friends). Managing these complex issues is a challenge due to the varied combinations of a motor (movement) and non-motor symptoms presented throughout the course of the condition.

Physiotherapy management[edit | edit source]

In a study looking into what constitutes expert practice in physical therapy, four domains were highlighted:[15]

- Multidimensional Knowledge Base - Where knowledge is drawn from learning institutions, mentors and importantly, the patients themselves. In this domain, knowledge extends beyond the pathology and movement disorder to include knowledge of the patient, support systems, activities at work and home as well as psychological and social development - even psychomotor status.

- Clinical Reasoning - In this domain the patient plays a central role in guiding the problem solving aspect of treatment. The patient's own goals and needs allow focus on the relevant functioning or limitation. Therapists constantly make use of the reflective process and enjoy the challenge of learning from their patients.

- Movement: A Central Focus on Skill - Using touch and hands-on therapy plays an integral aspect to expert therapy. Throughout the treatment process, both intervention and exercise prescription is done with functional movement in mind.

- Virtues: Caring and Commitment - Common in all expert's interactions with patients was their commitment and care for patients, demonstrated in time with the patients as well as other additional roles of patient advocacy.

Medical Management[edit | edit source]

Currently, there are no disease modifying pharmacological treatments for PD, with treatments being for symptomatic relief only.[16]

To alleviate motor symptoms in PD during the early stages of the disease, various drugs increasing the neuromotor activity at the dopaminergic sites are used. These include levodopa, monoamine oxidase inhibitors, dopamine agonists (DA) or a combination of the afore.[16]

Levodopa is generally prescribed as the first drug of choice in early PD (within 5 years of diagnosis). Common side-effects include nausea, dyskinesia, motor fluctuations, impulse control disorders, excessive daytime sleepiness, postural hypotension and hallucinations.[16]

DA's may also be prescribed. In a 2021 guideline on dopaminergic therapy it was recommended that detailed patient history be taken to screen for risk factors which may predispose a patient to some of the negative side affects. While many of these side-effects are common to those of levodopa, they are more prevalent in patients taking DA's.[16] Dopamine agonist withdrawal syndrome may be experienced when tapering of discontinuing DA therapy.[16]

While monoamine oxidase type B (MOA-B) can also be used in early PD treatment, it is associated with a higher risk of adverse effects with discontinuation when compared with levodopa.[16]

Common Motor Symptoms that Require Management[edit | edit source]

- Tremor is a prominent and early symptom of PD (not always present and is not a necessary feature for diagnosis).

- Slowness, or bradykinesia, a core feature of PD.

- Rigidity is the third prominent feature on examination.

- A combination of bradykinesia and rigidity leads to some other characteristic features of PD, such as micrographia.

- The fourth prominent feature of PD is gait disturbance, although this is typically a late manifestation. Flexed posture, ataxia, reduced arm swing, festination, march-a-petits-pas, camptocormia, retropulsion, and turning en bloc are popular terms to describe the gait in PD. Gait disorder is not an early feature of PD but is frequently described as it is easy to recognize and cinches the diagnosis in later stages[1].

Complications to Address[edit | edit source]

- Depression

- Dementia

- Laryngeal dysfunction

- Autonomic dysfunction

- Kyphosis leading to cardiopulmonary impairment[1]

Prognosis[edit | edit source]

The rate of progression of the disease may be predicted based on the following:[1]

- Males who have postural instability of difficulty with gait.

- Patients with older age at onset, dementia, and failure to respond to traditional dopaminergic medications tend to have early admission to nursing homes and diminished survival.

- Individuals with just tremors at the initial presentation tend to have a protracted benign course.

- Individuals diagnosed with the disease at older age combined with hypokinesia/rigidity tend to have a much more rapid progression of the disease.

The disorder: leads to disability of most patients within ten years; has a mortality rate three times the normal population.

Parkinson’s cannot yet be cured (treatment can improve symptoms but the quality of life is often poor)[1]. A lot of financial and other resources are being expended on research to find a cure.

Differential Diagnosis[edit | edit source]

- Essential tremor

- Huntington chorea

- Dementia with Lewy bodies

- Progressive supranuclear palsy

- Neuroacanthocytosis

- Normal pressure hydrocephalus

Resources[edit | edit source]

European Parkinson’s Disease Association[edit | edit source]

The European Parkinson’s Disease Association (EPDA) is a European Parkinson's umbrella organisation. They represent 45 member organisations and advocate for the rights and needs of more than 1.2 million people with Parkinson’s and their families.

The EPDA vision is to enable all people with Parkinson's in Europe to live a full life while supporting the search for a cure.

The group launched the European Parkinson’s Disease Standards of care Consensus Statement in the European Parliament in November 2011. The document defines what the optimal management of Parkinson’s should be and what good-quality care should consist of. The document is not only developed by experts in the field of Parkinson’s but includes the voice of people with Parkinson’s. In addition to this, they have produced some amazing resources to introduce people to the condition.

| [17] |

Parkinson's UK[edit | edit source]

The Parkinson’s UK website hosts a lot of information about Parkinson's and management of the condition. Local support groups are also available through Parkinson's UK and are an excellent resource available to persons with Parkinson's and Parkinsonism. Often exercise groups are also provided through these groups.

Move4Parkinson's[edit | edit source]

Move4Parkinson’s was set up by Margaret Mullarney who was diagnosed with Parkinson’s in 2004. The site is dedicated to educating, empowering and inspiring People with Parkinson’s and their families or carers (Parkinson’s communities) to gain the knowledge and skills they need to improve their Quality of Life. Margaret recommends the Five Elements Framework based on her personal experience:

National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke[edit | edit source]

The National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke (NINDS) provides a list of American based organizations:

Viartis[edit | edit source]

Viartis is an independent, non-commercial, and self-funded medical researcher specializing in Parkinson's. Viartis is not part of any other company, university or organization, and have no religious or political allegiances. They choose articles solely on the basis of their medical significance or potential interest, and you can register to receive information free of charge. The site provides links to a range of international organizations.

Parkinson's Conference, 2009[edit | edit source]

In September 2009, SPRING (the research interest group of the Parkinson’s Disease Society) hosted a conference on the effect of exercise on Parkinson’s. Bhanu Ramaswamy was part of the organizing committee with her AGILE / ACPIN Parkinson’s Project Officer hat on, alongside Vicki Goodwin, who was also invited to speak on her research. The conference explored known aspects plus issues yet to be discovered about the benefits of exercise for people with Parkinson's. Contributions were from invited participants from across the world in the hope of enabling proposals for new research collaboration to promote exercise as an essential component of therapy for Parkinson's.

General conference information can be accessed through the website

Below are videos of the two keynote presentations from the conference:

| [18] | [19] |

Related pages in Physiopedia[edit | edit source]

- Anatomy, Pathology, Prognosis, and Diagnosis

- Clinical Presentation

- Drugs for the Treatment of Parkinson's

- Physiotherapy - Referral and Assessment

- Physiotherapy - Management and Interventions

- Key Evidence and resources

References[edit | edit source]

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 1.5 1.6 1.7 1.8 Zafar S, Yaddanapudi SS. Parkinson disease. InStatPearls [Internet] 2019 Dec 4. StatPearls Publishing. Available from:https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK470193/ (last accessed 6.1.2020)

- ↑ Osborne JA, Botkin R, Colon-Semenza C, DeAngelis TR, Gallardo OG, Kosakowski H, Martello J, Pradhan S, Rafferty M, Readinger JL, Whitt AL. Physical therapist management of Parkinson disease: a clinical practice guideline from the American Physical Therapy Association. Physical therapy. 2022 Apr 1;102(4):pzab302.

- ↑ Xu L, Pu J. Alpha-synuclein in Parkinson’s disease: from pathogenetic dysfunction to potential clinical application. Parkinson’s disease. 2016 Aug 17;2016.

- ↑ Radiopedia Parkinson disease Available: https://radiopaedia.org/articles/parkinson-disease-1(accessed 17.3.2022)

- ↑ CHI health Parkinson's Disease - Causes, Symptoms & Treatment Available from:https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=9DLw3cCfbm0 (last accessed 6.1.2020)

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 Radiopedia PD Available:https://radiopaedia.org/articles/parkinson-disease-1?lang=gb (accessed 15.3.2022)

- ↑ Young CB, Reddy V, Sonne J. Neuroanatomy, basal ganglia. InStatPearls [Internet] 2023 Jul 24. StatPearls Publishing.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 8.2 Rubin JE, McIntyre CC, Turner RS, Wichmann T. Basal ganglia activity patterns in parkinsonism and computational modeling of their downstream effects. European Journal of Neuroscience. 2012 Jul;36(2):2213-28.

- ↑ Neuroscientifically Chall. 2-Minute Neuroscience: Basal Ganglia. Available from: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=OD2KPSGZ1No [last accessed 17/04/2024]

- ↑ Goetz CG. The history of Parkinson's disease: early clinical descriptions and neurological therapies. Cold Spring Harbor perspectives in medicine. 2011 Sep 1;1(1):a008862.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 11.2 11.3 11.4 Jankovic J, Tan EK. Parkinson’s disease: etiopathogenesis and treatment. Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery & Psychiatry. 2020 Aug 1;91(8):795-808.

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 12.2 12.3 Noyce AJ, Lees AJ, Schrag AE. The prediagnostic phase of Parkinson's disease. Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery & Psychiatry. 2016 Aug 1;87(8):871-8.

- ↑ Parkinson’s UK. The Incidence and Prevalence of Parkinson’s in the UK. London, UK. 2018.

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 14.2 Cova I, Priori A. Diagnostic biomarkers for Parkinson’s disease at a glance: where are we?. Journal of Neural Transmission. 2018 Oct;125:1417-32.

- ↑ Jensen GM, Gwyer J, Shepard KF, Hack LM. Expert practice in physical therapy. Physical therapy. 2000 Jan 1;80(1):28-43.

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 16.2 16.3 16.4 16.5 Pringsheim T, Day GS, Smith DB, Rae-Grant A, Licking N, Armstrong MJ, de Bie RM, Roze E, Miyasaki JM, Hauser RA, Espay AJ. Dopaminergic therapy for motor symptoms in early Parkinson disease practice guideline summary: a report of the AAN guideline subcommittee. Neurology. 2021 Nov 16;97(20):942-57.

- ↑ EPDA. Parkinson's - an overview - pt 1. Available from: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=pqeZDFnpLpg [last accessed 29/09/16]

- ↑ Professor Alice Nieuwboer c/o SPRING (Parkinson's UK). Exercise for Parkinson’s disease: the evidence under scrutiny. Available from: https://vimeo.com/8149682 [last accessed 29/09/16]

- ↑ Professor Michael Zigmond c/o SPRING (Parkinson's UK). Exercise and Parkinson’s disease: evidence for efficacy from cellular and animal studies. Available from: https://vimeo.com/8150672 [last accessed 29/09/16]