Ankle Osteoarthritis

Original Editors - Thijs Van Liefferinge as part of the Vrije Universiteit Brussel's Evidence-based Practice project.

Top Contributors -Scott Buxton, Rachael Lowe, Kim Jackson, Aminat Abolade, Admin, Maarten Cnudde, Thijs Van Liefferinge, Nupur Smit Shah, Lukas Van Orshoven, Uchechukwu Chukwuemeka, Shaimaa Eldib, Simisola Ajeyalemi, Caroline Akst, Arne Van De Winkel, Vidya Acharya, 127.0.0.1, Rucha Gadgil, Abbey Wright, Lauren Lopez, Lucinda hampton, Jess Bell, Evan Thomas, Khloud Shreif, Olajumoke Ogunleye and Ammar Suhail

Definition & Description[edit | edit source]

Ankle osteoarthritis is the occurrence of osteoarthritis (OA) in the ankle joint. The ankle joint consists of two synovial joints, namely the talocrural joint and the subtalar joint. In both joints, osteoarthritis can be diagnosed in the medial and lateral compartments.

The ankle joint is far less commonly affected by arthritis than other major joints. The reasons for this include differences in articular cartilage, joint motion, and the susceptibility of cartilage to inflammatory mediators. There is relatively good containment and conformity of the ankle joint, the talus is firmly bound on three sides by the fibula, tibial plafond and medial malleolus and their strong ligamentous attachments. This design potentially gives the ankle a better cartilaginous loading profile. The most common cause of end-stage arthritis of the ankle is trauma. Additional causative factors include arthropathies, chronic ankle instability, malalignment, and certain medical conditions, such as haemophilia.

Clinically Relevant Anatomy[edit | edit source]

Osteoarthritis of the ankle can occur in the joints of the Ankle, the main two being the Talocrural (True ankle joint) and Subtalar joints [1][2]. There is also a third ankle joint, the Inferior Tibiofibular joint, which does contribute to movement at the ankle but much less than its' counterparts[3], subsequently will be less of a focus.

Whenever considering the anatomy of a particular joint, it is essential to cast your eye and factor in influences from the joints above and below your particular joint in focus, in this case, the Knee and Foot, especially as it has been shown that differences in foot and knee characteristics influence rates of osteoarthritis[4]. As a quick consideration, think about the 28 bones and 30 joints of the foot, some 100 ligaments and the influence all of these have on biomechanics, balance and gait and the subsequent influence on the Talocrural and Subtalar joints[5].

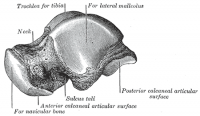

Talocrural Joint[edit | edit source]

The ankle joint is a synovial hinge joint comprised of hyaline-covered articular surfaces of the talus, the tibia as well as the fibula, allowing up to 20 degrees dorsiflexion and 50 degrees plantar flexion. The distal ends of the tibia and fibula are held together firmly by ligaments of the medial (Deltoid) and lateral ligament complexes of the ankle which can be damaged and contribute to ankle arthritis (Ankle Sprain). The ligaments hold the tibia and fibula into a deep bracket-like shape where the talus sits[3].

- The ROOF of the joint is the distal inferior surface of the tibia

- The MEDIAL SIDE of the joint is formed of the medial malleolus of the tibia

- The LATERAL SIDE of the joint is formed of the lateral malleolus of the fibula

The articular part of the talus looks like a cylinder and fits snugly into the bracket provided by the syndesmosis of the tibia and fibula, when looking down upon the talus the articular surface is wider anteriorly than posteriorly. Subsequently, this increases the congruent, stable nature of this joint when it is in dorsiflexion. As this is a synovial joint, a membrane is present as well as a fibrous membrane providing the same functions as any other synovial joint synovial membrane[3][3][3]

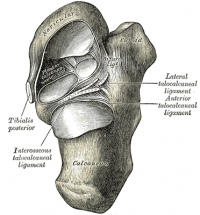

Subtalar Joint[edit | edit source]

The Subtalar joint is also known as the Talocalcaneal joint and is between:

- The large posterior calcaneal facet on the inferior surface of the talus; and

- The corresponding posterior facet on the superior surface of the calcaneus[3]

This joint, due to its orientation, allows the movements of inversion (0-35 degrees) and eversion (0-25 degrees). This must mean the joint allows some amount of glide and rotation. It is known as a simple synovial condyloid joint. There are a large number of strong ligaments supporting the:

- Anterior talocalcaneal ligament

- Posterior talocalcaneal ligament

- Lateral talocalcaneal ligament

- medial talocalcaneal ligament

Musculature[edit | edit source]

The muscles acting on the foot and ankle may not be directly involved in the basic pathological understanding of osteoarthritis of the ankle however, it can contribute to a more complex aetiology, but it is essential to provide targeted, specific rehabilitation of OA ankle. Simply put there are a large number of muscles acting upon these joints and they act in a similar way to the wrist and hand, this may aid your application and functional understanding.

Here is an unfinished list of some of the major muscles of the lower leg and foot, consider these in your rehabilitation and mechanism of pathology.

Posterior Compartment - Superficial[edit | edit source]

Posterior Compartment - Deep[edit | edit source]

Lateral Compartment[edit | edit source]

Anterior Compartment[edit | edit source]

Anatomy Tutorial Videos[edit | edit source]

| [7] | [8] |

| [9] | [10] |

Epidemiology & Etiology[edit | edit source]

Epidemiology[edit | edit source]

Idiopathic osteoarthritis is the most common joint disease in the world and estimates are that around 1% of OA occurs in the ankle which is, considering the rates of occurrence, relatively rare[11]. OA usually affects middle-aged - elderly population bases and is rarer under the age of 40, but not impossible. Causes usually are joint deterioration secondary to inflammatory changes, trauma, infection, vascular or neurological insults and poor biomechanics. These biomechanical insults could be due to excessive joint laxity, obesity, muscle weakness and muscle length all of which physiotherapy can influence and alter making physiotherapy an effective treatment option for consideration[12][13].

More commonly arthritic ankles are usually secondary to trauma or rheumatoid arthritis. This was confirmed by Saltzman et al, who analysed the different causes of ankle arthritis in the patients who were treated at the University of Iowa Orthopaedic Department by considering the current and previous medical history and mechanisms of injury as well as current presentation. Of the 639 cases between 1999-2004, 70% were post-traumatic, 12% were rheumatoid disease-related and only 7% were idiopathic osteoarthritis. So it can be considered a unique occurrence compared to other ankle arthritis[14].

Etiology[edit | edit source]

There are 2 types of Osteoarthritis: primary and secondary

Primary Osteoarthritis[edit | edit source]

This is the form of osteoarthritis in which you don't know what could trigger the disease. You can't infer anything from history, nor clinical or radiographic examination[15].

Compared with results reported for knee and hip, there is a substantially lower rate of primary ankle OA. Although early cartilage degeneration occurs, progression to severe grades of degeneration is not frequently observed[16]. This phenomenon is thought to be caused by the unique anatomic, biomechanical and cartilage characteristics of the ankle. Specifically, the ankle has a smaller contact area than the hip or knee in a load-bearing pattern. Subsequently, the pressure distribution is different which explains the differences between joints[17]. There is also a relatively higher cartilage resistance in the ankle, which might protect it from degenerative changes leading to primary OA. This higher cartilage resistance in the ankle is due to the fact that the ankle is primarily a rolling joint with congruent surfaces at a high load, which allows it to withstand large pressures[18]. Although the ankle cartilage is thinner compared with knee or hip cartilage, it shows higher compressive stiffness and proteoglycan density, lower matrix degradation and less response to catabolic stimulations. So the ankle is not generally a site of primary OA (This occurs only in approximately 7% of all ankle OA cases[11].

Secondary Osteoarthritis[edit | edit source]

This last form can be caused by trauma, metabolic disease, congenital malformations, premature menopause, etc. Sometimes, it can happen that a patient is suffering from secondary osteoarthritis before the age of 40.

In most cases ankle OA is developed secondary to trauma such as fractures of the malleoli, the tibial plafond, the talus, maybe some Varus alignment and also potentially ankle ligament injuries[12]. The mechanism of ligament injuries leading to OA may be twofold: either an acute osteochondral lesion which can occur in severe ankle sprains, or chronic change in ankle mechanics leading to repetitive cartilage degeneration, as in recurrent or chronic unstable ankles[19]. Due to the fact that this secondary mechanism is the leading cause of ankle OA, sufferers are usually younger than patients with primary OA.

Characteristics & Clinical Presentation[edit | edit source]

As with osteoarthritis of any joint, there are subjective and objective patterns which match the symptoms of osteoarthritis you need to be aware of, below is a table with the most common signs.

| Joint Pain |

Usually affects 1 to a few joints at a time Insidious onset, slow progression over time Variable Intensity Potentially relapsing and intermittent Worse in weight-bearing Relieved by rest initially May have severe night pain |

| Stiffness |

Short-lived early morning stiffness (<30 mins) Short-lived inactivity-related stiffness |

| Swelling | Some sufferers report swelling, mild effusion and deformity |

| Age | Usually 40yr+ |

| Systemic Symptoms | Absent |

| Appearance |

Swelling over bony and soft tissue surfaces Protective resting position Deformity Global muscle atrophy |

| Feel |

Absence of warmth Swelling - bony or effusion Effusion - cold and small Joint-line tenderness Peri-articular tenderness |

| Movement |

Coarse crepitus Decrease ROM Weak local muscles |

| Subjective Markers |

Morning stiffness Manual labour jobs Low-level pain with some periods of severe Deep pain "Crunching, clicking noises" Like putting heat on the knee to ease pain Aggravated by stairs or running |

Differential Diagnosis[edit | edit source]

As with any suspect of joint pathology, it is important to differentiate between mechanical and inflammatory pathology. This is especially valid for the ankle as we know the rates of an inflammatory cause of ankle osteoarthritis are higher than primary or secondary onset osteoarthritis.

Outcome Measures[edit | edit source]

- Visual Analogue Scale (VAS) to determine pain in the ankle due to OA.

- Goniometer to determine the range of motion of the two synovial joints of the ankle.

- The Intermittent and Constant Osteoarthritis Pain index (ICOAP)

- The Algofunctional Index (AFI)

- The Western Ontario and McMaster Universities osteoarthritis index (WOMAC) The last three are questionnaires to determine ankle OA[21]

- Dynamic Gait Index

- Oswestry Disability Index

- Foot and Ankle Disability Index

Examination[edit | edit source]

The objective examination of ankle OA consists of[22][23][21]:

- Observation, specifically looking at:

- Swelling/effusion of the ankle (and grade of this swelling)

- Active inflammatory process

- Gait

- Looking for muscular atrophy

- Expression of pain

- Joint deformity

- Palpation:

- Feeling deep within the joints' articular surfaces, searching for specific tenderness and reproduction of the patient's symptoms

- Feeling for any crepitus on movement

- Feeling for the type of swelling/effusion

- Feel for temperature

- Any sensation loss in a dermatomal pattern

- Basic Objective Tools

- ROM active and passive, any limitations, feel for crepitus, where pain or stiffness onset, reproduction of symptoms

- Strength, any weakness in specific muscles or groups globally

- Functional tasks such as sit-to-stand, steps, squats and quick changes of direction

- Special Tests

- Talar tilt to check for instability

- Anterior and posterior drawer to test for instability and arthrokinematics

- Balance and proprioception such as a single leg stand

Medical Management[edit | edit source]

Depending on the type and the severity of OA, there are several medical and nonsurgical treatments:

- Anti-inflammatory medication to counter periodic inflammation.

- An intra-articular injection of corticosteroids, a drug that reduces inflammation.

- An injection of hyaluronic acid in the joint. This viscosupplementation refers to the concept of synovial fluid replacement with intra-articular injections of hyaluronic acid for the relief of pain, associated with OA[23][24][25].

There are also surgical treatments. What surgical treatment is required depends on the location of OA, how severely the joint is affected and the degree of experiencing the condition. Sometimes more than one type of surgical treatment is needed[23]. The most common surgical procedures in ankle OA are:

- Cleaning the joint with keyhole surgery: arthroscopy.

- Securing the joint: arthrodesis.

- replacing of the joint: ankle prosthesis[26].

Physical Therapy Management[edit | edit source]

Recent studies suggest that moderate exercise (physical activity) is safe and effective for the treatment of ankle OA. This physical activity leads to less experienced pain, stronger muscles around the ankle, improvement of range of motion and improved balance, coordination and stability of the ankle, which all contribute to improved physical function. These exercises should take place under the supervision of a physiotherapist[21] [22][27]

- Exercise: is most effective when it consists of a combination of:

- Strength training: muscle strengthening exercises for Gastrocnemius, Soleus, Tibialis Anterior and Peronei (repeated exercises with Theraband).

- Endurance training: exercises to increase aerobic capacity. Run training and cycling are recommended.

- Mobilizing exercises: range of motion exercises. Exercises including plantar flexion, dorsiflexion, inversion and eversion of the ankle are recommended.

- Balance and proprioceptive training if there is instability of the ankle joint. Exercises (plantarflexion, dorsiflexion, inversion and eversion of the ankle) with airex cushion and wobble board are recommended.

- Functional exercises like standing on one leg, walking on various surfaces, sitting down and getting up, getting up from a lying position, and climbing stairs are also recommended because these exercises include several components simultaneously[21] [22].

- Hydrotherapy: is recommended by international guidelines. It can be useful in cases where the pain is too severe to exercise on dry land. Some studies suggest that swimming and water exercises (including plantar flexion, dorsiflexion, inversion and eversion of the ankle) are excellent for OA patients. It provides relaxation (in the case of a warm bath), a decreased pain level and improved mobility[21] .

- Passive mobilisation: This includes mobilisations for plantarflexion, dorsiflexion, inversion and eversion of the ankle. It has proved to be effective in eliminating pain and joint immobility. It is only effective in combination with active exercise therapy. Anterior and posterior ankle joint glide can be applied[21].

- Massage: of the muscles around the ankle. This is not effective for ankle OA. However careful and progressive massage of a pain point can lead to temporary waiver of localized pain [21].

- Thermotherapy: can be effective to warm up tissues (in case of very stiff joints) before exercise. It is also useful for patients with problems to relax. In case of inflammation of the joint, the application of cold ice packs is designated[21].

- Electrotherapy: has not proved to be effective for ankle OA. It may be considered if there is severe pain and it serves to support exercise[21].

- Ultrasound: is not advised in the treatment of ankle OA [21].

- The use of both laser and TENS can have significant effects on osteoarthritis. However, the evidence for the effect of laser is weaker than for TENS. [28]

- External support devices: have not proved to be effective for ankle OA. However bracing, taping and shoe inserts may help take away the pain[21].

- Education of the patient and self-management are both recommended. [29]The physiotherapist can explain about the importance of exercises and how it is helpful in prevention of further damage to the joint.[30]

References[edit | edit source]

- ↑ Parkway Physiotherapy. (2009) Osteoarthritis of the Ankle. http://www.parkwayphysiotherapy.ca/article.php?aid=122.fckLR

- ↑ Reginster JY, Pelletier JP, Martel-Pelletier J, Henrotin Y, editors. Osteoarthritis: Clinical and experimental aspects. Springer Science & Business Media; 2012 Dec 6.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 Drake, R. Vogl, A. Mitchell, A. Gray's Anatomy for Students. 2nd ed. 2010: 609. Churchill Livingstone: Elsevier: Philadelphia.

- ↑ Reilly, A. Barker, L. Shamley D. Sandall S. Influence of foot characteristics on the site of lower limb osteoarthritis. Foot and Ankle International. 2006;(3):206-211

- ↑ American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons. Arthritis of the Foot and Ankle (2008) [ONLINE] Available from: http://orthoinfo.aaos.org/topic.cfm?topic=a00209 Accessed 10/05/2014

- ↑ Ankle Joint - Anatomy Zone - Available from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=lPLdoFQlZXQ

- ↑ Muscles of the Leg - Part 1 - Posterior Compartment - Antomy Zone. Available from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=F1J0HbV2n5s

- ↑ Muscles of the Leg - Part 2 - Anterior and Lateral Compartment - Anatomy Zone - Available from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=83_ctEOFkhM

- ↑ Muscles of the Foot Part 1 - Anatomy Zone - Available from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ocUiJYXebHs

- ↑ Muscles of the Foot Part 2 - Anatomy Zone - available from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=aOBHTkSamWw

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 Moskowitz RW. Osteoarthritis, diagnosis and management. WB Saunders Company; 1984.

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 Valderrabano V, Horisberger M, Russell I, Dougall H, Hintermann B. Etiology of ankle osteoarthritis. Clinical Orthopaedics and Related Research®. 2009 Jul;467(7):1800-6.

- ↑ Zhang Y, Jordan JM. Epidemiology of osteoarthritis. Clinics in geriatric medicine. 2010 Aug 1;26(3):355-69.

- ↑ Saltzman CL, Salamon ML, Blanchard GM, Huff T, Hayes A, Buckwalter JA, Amendola A. Epidemiology of ankle arthritis: report of a consecutive series of 639 patients from a tertiary orthopaedic center. The Iowa orthopaedic journal. 2005;25:44.

- ↑ http://www.physio-pedia.com/Osteoarthritis

- ↑ Muehleman C, Berzins A, Koepp H, Eger W, Cole AA, Kuettner KE, Sumner DR. Bone density of the human talus does not increase with the cartilage degeneration score. The Anatomical Record: An Official Publication of the American Association of Anatomists. 2002 Feb 1;266(2):81-6.

- ↑ Kimizuka M, Kurosawa H, Fukubayashi T. Load-bearing pattern of the ankle joint. Archives of orthopaedic and traumatic surgery. 1980 Mar;96(1):45-9.

- ↑ Wynarsky GT, Greenwald AS. Mathematical model of the human ankle joint. Journal of biomechanics. 1983 Jan 1;16(4):241-51.

- ↑ Muehleman C, Berzins A, Koepp H, Eger W, Cole AA, Kuettner KE, Sumner DR. Bone density of the human talus does not increase with the cartilage degeneration score. The Anatomical Record: An Official Publication of the American Association of Anatomists. 2002 Feb 1;266(2):81-6.

- ↑ Abhishek A, Doherty M. Diagnosis and clinical presentation of osteoarthritis. Rheumatic Disease Clinics. 2013 Feb 1;39(1):45-66.

- ↑ 21.00 21.01 21.02 21.03 21.04 21.05 21.06 21.07 21.08 21.09 21.10 Vogels EM, Hendriks HJ, Van Baar ME, Dekker J, Hopman-Rock M, Oostendorp RA, Hulligie WA, Bloo H, Hilberdink WK, Munneke M, Verhoef J. KNGF-richtlijn Artrose heup-knie. Nederlands tijdschrift voor Fysiotherapie. 2001;111:1-34.

- ↑ 22.0 22.1 22.2 van Nugteren K, Winkel D, editors. Onderzoek en behandeling van artrose en artritis. Bohn Stafleu van Loghum; 2010 May 13.

- ↑ 23.0 23.1 23.2 Patientenbelangen. (2008) Voet- en enkelartrose. http://www.patientenbelangen.nl/docs/File/Folders/Voet-en-enkelartrose.pdf.fckLR

- ↑ Sun SF, Chou YJ, Hsu CW, Chen WL. Hyaluronic acid as a treatment for ankle osteoarthritis. Current reviews in musculoskeletal medicine. 2009 Jun;2(2):78-82.

- ↑ Conduah AH, Baker III CL, Baker Jr CL. Managing joint pain in osteoarthritis: safety and efficacy of hylan GF 20. Journal of pain research. 2009;2:87.

- ↑ Saltzman CL, Kadoko RG, Suh JS. Treatment of isolated ankle osteoarthritis with arthrodesis or the total ankle replacement: a comparison of early outcomes. Clinics in Orthopedic Surgery. 2010 Mar 1;2(1):1-7.

- ↑ Fransen M, McConnell S, Bell MM. Exercise for osteoarthritis of the hip or knee. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2001(2).

- ↑ Bjordal JM, Johansen O, Holm I, Zapffe K, Nilsen EM. The effectiveness of physical therapy, restricted to electrotherapy and exercise, for osteoarthritis of the knee.

- ↑ Peter WF, Jansen MJ, Hurkmans EJ, Bloo H, Dekker-Bakker LM, Dilling RG, Hilberdink WK, Kersten-Smit C, Rooij MD, Veenhof C, Vermeulen HM. Physiotherapy in hip and knee osteoarthritis: development of a practice guideline concerning initial assessment. Treatment and evaluation. Acta reumatologica portuguesa. 2011 Sep 30;36(3):268-81.

- ↑ McCarron LV, Al-Uzri M, Loftus AM, Hollville A, Barrett M. Assessment and management of ankle osteoarthritis in primary care. bmj. 2023 Jan 4;380.