Visual Analogue Scale

Original Editor - Venus Pagare

Top Contributors - Venus Pagare, Kim Jackson, Khloud Shreif, Evan Thomas, Rebecca Willis, Scott Buxton, Vanessa Rhule, Lauren Lopez, Melissa Coetsee, Admin and WikiSysop

Introduction[edit | edit source]

A Visual Analogue Scale (VAS) is one of the pain rating scales used for the first time in 1921 by Hayes and Patterson[1]. It is often used in epidemiologic and clinical research to measure the intensity or frequency of various symptoms. For example, the amount of pain that a patient feels ranges across a continuum from none to an extreme amount of pain. From the patient's perspective, this spectrum appears continuous; their pain does not take discrete jumps, as a categorization of none, mild, moderate and severe would suggest. It was to capture this idea of an underlying continuum that the VAS was devised.[2]

Purpose[edit | edit source]

The pain VAS is a unidimensional measure of pain intensity, used to record patients’ pain progression, or compare pain severity between patients with similar conditions. VAS has been widely used in diverse adult populations for example; those with rheumatic diseases, patients with chronic pain, cancer[3], or cases with allergic rhinitis[4]. In addition to rating pain, it has been used to evaluate mood[5], appetite, asthma, dyspepsia, and ambulation[1], and it can be used as a simple, valid, and effective tool to assess disease control[4].

Structure, Orientation, and Response Options[edit | edit source]

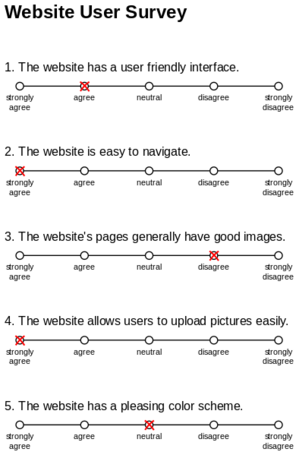

VAS can be presented in a number of ways, including:

- Numerical rating scales[3], scales with a middle point, graduations, or numbers[6].

- Curvilinear analog scales, meter-shaped scales.

- "Box-scales" consist of circles equidistant from each other (one of which the subject has to mark).

- Graphic rating scales or Likert scales with descriptive terms at intervals along a line [7].

The most simple VAS is a straight horizontal line of fixed length, usually 100 mm. The ends are defined as the extreme limits of the parameter to be measured (symptom, pain, health)[8] orientated from the left (worst) to the right (best). In some studies, horizontal scales are orientated from right to left, and many investigators use vertical VAS.[7]

No difference between horizontal and vertical VAS has been shown in a survey involving 100 subjects[9] but other authors have suggested that the two orientations differ with regard to the number of possible angles of view.[10][11]Reproducibility has been shown to vary along 100-mm and along a horizontal VAS[12]. The choice of terms to define the anchors of a scale has also been described as important[7].

Administration[edit | edit source]

- They are generally completed by patients themselves but are sometimes used to elicit opinions from health professionals.

- The patient marks on the line the point that they feel represents their perception of their current state.

- The VAS score is determined by measuring in millimetres from the left hand end of the line to the point that the patient marks.[2]

Recall Period for items[edit | edit source]

Recall period for items varies, but most commonly respondents are asked to report “current” pain intensity or pain intensity “in the last 24 hours.”

Scoring and Interpretation[edit | edit source]

Using a ruler, the score is determined by measuring the distance (mm) on the 10-cm line between the “no pain” anchor and the patient’s mark, providing a range of scores from 0–100. A higher score indicates greater pain intensity. Based on the distribution of pain, VAS scores in post-surgical patients (knee replacement, hysterectomy, or laparoscopic myomectomy) who described their postoperative pain intensity as none, mild, moderate, or severe, the following cut points on the pain VAS have been recommended: no pain (0–4 mm), mild pain(5-44 mm), moderate pain (45–74 mm), and severe pain (75–100 mm). Normative values are not available. The scale has to be shown to the patient otherwise it is an auditory scale, not a visual one. A recent study stated that "the preferred paper-based VAS item is with a horizontal, 8-cm long, 3 DTP ('desktop publishing point’) wide, black line, with flat line endpoints, and the ascending numerical anchors ‘0’ and ‘10’"[14].

Merits and Demerits[edit | edit source]

The VAS is widely used due to its simplicity and adaptability to a broad range of populations and settings.

Merits

- VAS is more sensitive to small changes than are simple descriptive ordinal scales in which symptoms are rated, for example, as mild or slight, moderate, or severe to agonizing.

- These scales are of most value when looking at change within individuals.

- The VAS takes < 1 minute to complete.

- Easy to use with routine treatment.

- No training is required other than the ability to use a ruler to measure the distance to determine a score.

- Minimal translation difficulties have led to an unknown number of cross-cultural adaptations.

- Obtained data from VAS can be converted parametrically to an interval-scale level[15].

Demerits

- However, assessment is clearly highly subjective.

- Are of less value for comparing across a group of individuals at one-time point.

- It could be argued that a VAS is trying to produce interval/ratio data out of subjective values that are at best ordinal.

- The VAS is administered as a paper and pencil measure or digital. As a result, it cannot be administered verbally or by phone[15].

- Caution is required when photo-copying the scale as this may change the length of the 10-cm line also, the same alignment of scale should be used consistently within the same patient.

Thus, some caution is required in handling such data.[2][16]

Obtaining the scale[edit | edit source]

The pain VAS is available in the public domain at no cost.

Psychometric Information[edit | edit source]

Method of development.[edit | edit source]

The pain VAS originated from continuous visual analog scales developed in the field of psychology to measure well-being. Woodforde and Merskey first reported the use of the VAS pain scale with the descriptor extremes “no pain at all” and “my pain is as bad as it could possibly be” in patients with a variety of conditions. Subsequently, others reported the use of the scale to measure pain in rheumatology patients receiving pharmacologic pain therapy. While variable anchor pain descriptors have been used, there does not appear to be any rationale for selecting one set of descriptors over another.

Acceptability[edit | edit source]

The pain VAS requires little training to administer and score and has been found to be acceptable to patients. However, older patients with cognitive impairment may have difficulty understanding and therefore completing the scale. Supervision during completion may minimize these errors.

Reliability[edit | edit source]

Test–retest reliability has been shown to be good, but higher among literate (r= 0.94, P= 0.001) than illiterate patients (r = 0.71,P= 0.001) before and after attending a rheumatology outpatient clinic.[17]

High reliability when it is used for acute abdominal pain and ICC = 0.99 [95%CI 0.989 to 0.992][18], and moderate to good reliability for disability in patients with chronic musculoskeletal pain[19].

Validity[edit | edit source]

In the absence of a gold standard for pain, criterion validity cannot be evaluated. For construct validity, in patients with a variety of rheumatic diseases, the pain VAS has been shown to be highly correlated with a 5-point verbal descriptive scale (“nil,” “mild,” “moderate,” “severe,” and “very severe”) and a numeric rating scale (with response options from “no pain” to “unbearable pain”), with correlations ranging from 0.71–0.78 and 0.62–0.91, respectively)[20]. The correlation between vertical and horizontal orientations of the VAS is 0.99[9].

Ability to detect a change[edit | edit source]

In patients with chronic inflammatory or degenerative joint pain, the pain VAS has demonstrated sensitivity to changes in pain assessed hourly for a maximum of 4 hours and weekly for up to 4 weeks following analgesic therapy (P=0.001). In patients with rheumatoid arthritis, the minimal clinically significant change has been estimated as 1.1 points on an 11-point scale (or 11 points on a 100-point scale). A minimum clinically important difference of 1.37 cm has been determined for a 10-cm pain VAS in patients with rotator cuff disease evaluated after 6 weeks of nonoperative treatment[21]

References[edit | edit source]

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Delgado DA, Lambert BS, Boutris N, McCulloch PC, Robbins AB, Moreno MR, Harris JD. Validation of digital visual analog scale pain scoring with a traditional paper-based visual analog scale in adults. Journal of the American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons. Global research & reviews. 2018 Mar;2(3).

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 D. Gould et al. Visual Analogue Scale (VAS). Journal of Clinical Nursing 2001; 10:697-706

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 Hjermstad MJ, Fayers PM, Haugen DF, Caraceni A, Hanks GW, Loge JH, Fainsinger R, Aass N, Kaasa S, European Palliative Care Research Collaborative (EPCRC. Studies comparing numerical rating scales, verbal rating scales, and visual analogue scales for assessment of pain intensity in adults: a systematic literature review. Journal of pain and symptom management. 2011 Jun 1;41(6):1073-93.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 Klimek L, Bergmann KC, Biedermann T, Bousquet J, Hellings P, Jung K, Merk H, Olze H, Schlenter W, Stock P, Ring J. Visual analogue scales (VAS): Measuring instruments for the documentation of symptoms and therapy monitoring in cases of allergic rhinitis in everyday health care. Allergo journal international. 2017 Feb;26(1):16-24.

- ↑ Yeung AW, Wong NS. The historical roots of visual analog scale in psychology as revealed by reference publication year spectroscopy. Frontiers in Human Neuroscience. 2019 Mar 12;13:86.

- ↑ Haefeli M, Elfering A. Pain assessment. European Spine Journal. 2006 Jan;15(1):S17-24.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 Scott J, Huskisson EC. Graphic representation of pain. Pain 1976;2:175-84

- ↑ Streiner DL,Norman GR. Health measurement scales: a practical guide to their development and use. New York; Oxford University Press,1989

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 Scott J, Huskisson EC. Vertical or horizontal visual analogue scales. Ann Rheum Dis 1979;38:560

- ↑ Aun C, Lam YM, Collect B. Evaluation of the use of visual analogue scale in Chinese patients. Pain 1986; 25:215-21

- ↑ Stephenson NL, Herman J. Pain measurement: a comparison using horizontal and vertical visual analogue scales. Appl Nurs Res. 2000 Aug 1;13(3):157-8.

- ↑ Joos E, Peretz A, Beguin S,et al. Reliability and reproducibility of visual analogue scale and numeric rating scale for therapeutic evaluation of pain in rheumatic patients. J Rheumatol 1991; 18:1269-70

- ↑ Sport for Life. Visual Analog Scale. Available from: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=7_7O0M1U-54[last accessed 27/3/2022]

- ↑ Weigl K, Forstner T. Design of paper-based visual analogue scale items. Educ Psychol Meas. 2021 Jun;81(3):595-611.

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 Klimek L, Bergmann KC, Biedermann T, Bousquet J, Hellings P, Jung K, Merk H, Olze H, Schlenter W, Stock P, Ring J. Visual analogue scales (VAS): Measuring instruments for the documentation of symptoms and therapy monitoring in cases of allergic rhinitis in everyday health care. Allergo journal international. 2017 Feb;26(1):16-24.

- ↑ Haefeli M, Elfering A. Pain assessment. European Spine Journal. 2006 Jan;15(1):S17-24.

- ↑ Ferraz MB, Quaresma MR, Aquino LR, Atra E, Tugwell P, Goldsmith CH. Reliability of pain scales in the assessment of literate and illiterate patients with rheumatoid arthritis. The Journal of rheumatology. 1990 Aug 1;17(8):1022-4.

- ↑ Gallagher EJ, Bijur PE, Latimer C, Silver W. Reliability and validity of a visual analog scale for acute abdominal pain in the ED. Am J Emerg Med. 2002 Jul 1;20(4):287-90.

- ↑ Boonstra AM, Preuper HR, Reneman MF, Posthumus JB, Stewart RE. Reliability and validity of the visual analogue scale for disability in patients with chronic musculoskeletal pain. Int J Rehab Res. 2008 Jun 1;31(2):165-9.

- ↑ Downie WW, Leatham PA, Rhind VM, Wright V, Branco JA, Anderson JA. Studies with pain rating scales. Ann Rheum Dis 1978;37:378–81.

- ↑ Joyce CR, Zutshi DW, Hrubes V, Mason RM. Comparison of fixed interval and visual analogue scales for rating chronic pain. European journal of clinical pharmacology. 1975 Nov;8(6):415-20.