Ankle Sprain

Original Editor - Dale Boren, Michael Kauffmann, Pieter Jacobs as part of the Vrije Universiteit Brussel Evidence-Based Practice Project

Top Contributors - Naomi O'Reilly, Laura Ritchie, Rachael Lowe, Admin, Michael Kauffmann, Kim Jackson, Pieter Jacobs, Reem Ramadan, Cath Young, Alex Palmer, Roberto Monfermoso, Dale Boren, Andrew Costin, Adam Vallely Farrell, Corentin Meese, 127.0.0.1, Scott Cornish, Asha Bajaj, Simisola Ajeyalemi, Rucha Gadgil, Scott Buxton, Anas Mohamed, Khloud Shreif, Nupur Smit Shah, WikiSysop, Fasuba Ayobami, Tony Lowe, Lisa Parijs, Candace Goh, Evan Thomas, Shaimaa Eldib, Wanda van Niekerk, Anouck Leo, Olajumoke Ogunleye and Kai A. Sigel

Introduction[edit | edit source]

An ankle sprain is a common musculoskeletal injury that involves the stretch or tear (partial or complete) of the ligaments of the ankle. They occur when the ankle moves outside of its normal range of motion which can be seen mostly in active and sports populations[1].

Epidemiology[edit | edit source]

The ankle joint is the second joint that is most likely to be injured in sport and the ankle sprain is the most common injury in the ankle joint. [2]

The most common type of ankle sprains were the lateral ligament injuries making up approximately 85% of all ankle sprains and the least common were acute medial and syndesmotic ankle sprains with females having the highest rate of ankle sprain incidence than males and children [3].

In the United States of America, the total cost of ankle sprains is approximately $2 billion[4] [5]. According to a study conducted on 39,340 individuals with an ankle sprain over the period of 4 years in the United States Military Health System, results showed that poor and delayed rehabilitation after initial sprain increases the chance of this injury recurrence and increases the occurrence of ankle-related medical visits[6] [7].

A meta-analysis by Doherty et al, found that indoor sports such as Basketball carry the greatest risk of ankle sprain with an incidence of 7 per 1,000 cumulative exposures[8]. Severe ankle sprains occur commonly in basketball players with recurrence rates amongst these players being greater than 70%[9]. According to a study on elite Australian basketball players, McKay et al (2001), reported that the rate of ankle injury was 3.85 per 1000 participations which caused 37 ankle-injured athletes to miss 81.5 weeks of play and [10]. Athletes with chronic ankle instability tend to miss practices and competition, require ongoing care in order to remain physically active, and display sub-optimal performance.

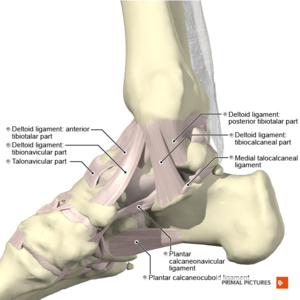

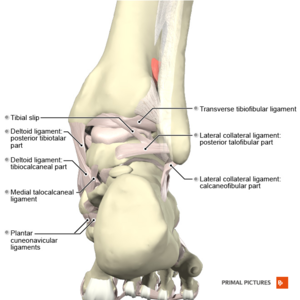

Clinically Relevant Anatomy[edit | edit source]

For the lateral ankle ligament complex, the most frequently damaged ligament is the Anterior Talofibular ligament (ATFL). The mechanism of sprain injury of the ATFL and Calcaneofibular ligament (CFL) is when a plantar-flexed foot is forcefully inverted. In this case, this implies that the Calcaneofibular (CFL) and posterior Talofibular ligaments (PTFL) are less likely to sustain damaging loads. The PTFL is rarely injured unless its associated with a talus dislocation[11].

As for the medial side the strong, deltoid ligament complex consisting of posterior Tibiotalar (PTTL), Tibiocalcaneal (TCL), Tibionavicular (TNL) and anterior Tibiotalar ligaments (ATTL) are injured with forceful pronation and rotation movements of the hindfoot.[12]

The stabilizing ligaments of the distal Tibio-fibular syndesmosis are the anterior-inferior, posterior-inferior, and transverse tibio-fibular ligaments, the interosseous membrane and ligament, and the inferior transverse ligament. A syndesmotic (high ankle) sprain occurs with combined external rotation of the leg and dorsiflexion of the ankle[13].

Risk Factors[edit | edit source]

Several intrinsic and extrinsic risk factors predispose an athlete to chronic ankle instability.

- Extrinsic factors: previous history of sprain (A previous sprain may compromise the strength and integrity of the stabilizers and interrupt sensory nerve fibers)[14]

- Intrinsic factors: Sex, height, weight, limb dominance, postural sway and foot anatomy[15]

Other extrinsic factors include taping, bracing, shoe type, competition duration and intensity of activity.

Mechanism of Injury/Pathological Process[edit | edit source]

Lateral ankle sprains usually occur during a rapid shift of body center of mass over the landing or weight-bearing foot. The ankle rolls outward, whilst the foot turns inward causing the lateral ligament to stretch and tear. When a ligament tears or is overstretched its previous elasticity and resilience rarely returns back to normal. Some researchers have described situations where return to play is allowed too early, compromising sufficient ligamentous repair.[16] Reports have proposed that the greater the level of plantar flexion, the higher the likelihood of sprain[17].

Based on a study conducted on ninety-four Brazilian young competitive volley and basketball athletes, results showed that, the likelihood of ankle sprains were 80.6% when the athlete had the left lower leg dominant, peroneus brevis electromyographic response time greater than 80ms, use of shoes without dampers and playing positions[18].

In addition to that, Yeung et al, 1994, in an epidemiological study of unilateral ankle sprains, reported that the dominant leg is 2.4 times more vulnerable to sprain than the non-dominant one. [9] [7]. A less common mechanism of injury involves forceful eversion movement at the ankle injuring the strong deltoid ligament.

| Aspect | Mechanism of injury | Ligaments |

|---|---|---|

| Lateral | Inversion and plantarflexion | anterior talofibular ligament calcaneo-fibular ligament posterior talofibular ligament |

| Medial | Eversion | posterior tibiotalar ligament tibiocalcaneal ligament tibionavicular ligament anterior tibiotalar ligament |

| High | External rotation and dorsiflextion | anterior-inferior tibiofibular ligament posterior-inferior tibiofibular ligamen transverse tibiofibular ligament interosseous membrane interosseous ligament inferior transverse ligament |

Clinical Presentation[edit | edit source]

The signs and symptoms of ankle sprain vary widely depending on the type and severity of the injury and include:

- pain especially when putting weight on the affected foot

- tenderness upon palpation of the ankle joint

- bruising, edema and swelling

- limitation in range of motion and instability at the level of the joint[1]

- complains of cold foot or paresthesia which could imply neurovascular compromise of peroneal nerve[19]

- inversion injury or forceful eversion injury to the ankle

- previous history of ankle injuries or instability

- special Tests: positive signs in Anterior Draw, Talar Tilt or Squeeze Test (depending on the structures involved)

Note that: Passive inversion or plantar flexion with inversion should replicate symptoms for a lateral ligament sprain and passive eversion should replicate symptoms for a medial ligament sprain.[20]

Differential Diagnosis[edit | edit source]

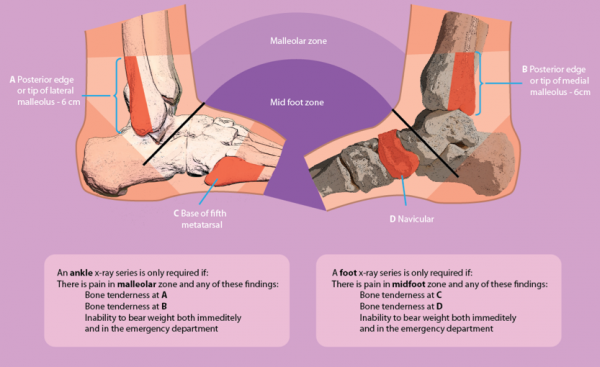

The differential diagnosis of an ankle sprain includes tendon rupture, tendinopathy, fracture, tendon subluxation, and a number of other conditions. The diagnosis is based on the history of trauma and examination findings where the use of an ultrasound can be used to identify whether there is a tendon injury and in chronic cases where the Ottowa Rules are not applicable, diagnostic imaging can be used to clarify the diagnosis[21].

The Ottawa Ankle Clinical Prediction Rules are an accurate tool according to 27 studies conducted on 15,581 individuals[22] to exclude fractures within the first week after an ankle injury and to reduce the number of unnecessary radiographs. [23]

Additional differential diagnosis to look out for:[24]

- Impingement

- Tarsal Tunnel Syndrome

- Sinus Tarsi Syndrome

- Cartilage or osteochondral injuries

- Peroneal Tendinopathy or subluxation

- Posterior Tibial Tendon Dysfunction

Classification of Ankle Sprain[edit | edit source]

Ankle sprains can be classified according to various grading systems, each having their specific strengths and weaknesses. Therapists employ different systems specific for the patient's case and according to their background education for effective continuity of care[25].

One of the grading systems used for classifying ankle sprains focuses on a single ligament:

- Grade I represents slight stretching and damage to fibers of the ligament

- Grade II represents partial tear of the ligament

- Grade III represents complete rupture of the ligament[26]

As there are multiple ligaments across the ankle joint, it may not be always straight forward to use a grading system that is designed for describing the state of a single ligament unless it is certain that only a single ligament is injured. For this reason another grading system is used to classify ankle sprains based on the number of ligaments injured[27]. It is, however, hard to determine the exact number of ligaments torn unless there is a clear high quality radiographic imaging or surgical evidence.

A different system which can be adopted is based on the severity of sprain injury:

- Grade I: Mild impairment - Minimal swelling and tenderness with little impact on function

- Grade II: Moderate impairment - Moderate swelling, pain and tenderness with decreased range of motion and ankle instability

- Grade III: Severe impairment - Significant swelling, tenderness, loss of function and marked instability[28]

Outcome Measures[edit | edit source]

- Lower Extremity Functional Scale (LEFS)

- Foot and Ankle Ability Measure (FAAM)

- Foot and Ankle Disability Index (FADI)

- Star Excursion Balance Test

Clinical Examination[edit | edit source]

An ankle sprain involves multiple structures, therefore a full foot and ankle assessment is recommended[25]. The assessment of the injured ankle involves taking past medical history of the patient to note whether the patient has had previously a similar or different or no injury at all which is crucial for aiding in the diagnosis. After taking the past medical history of the patient, its important to observe the patient's gait pattern and posture and furthermore note any deformity, mal-alignment, atrophy, presence of edema or ecchymosis. Following that, palpating the affected structures is necessary to note for tenderness over boney prominence, muscle or even ligaments and then assessing the patient's passive and active range of motion of the patient[29].

| [30] | [31] |

Special Tests[edit | edit source]

- Anterior Drawer Test - tests the Anterior Talo-Fibular Ligament

- Talar Tilt Test- tests the Calcaneofibular Ligament

- Posterior Draw - tests the Posterior Talofibular Ligament

- Squeeze test - tests for a Syndesmotic sprain

- External rotation stress test (Kleiger’s test) - tests for a Syndesmotic sprain[32]

Physical Therapy Management[edit | edit source]

Physical therapy plays an important role in the treatment of ankle sprains especially in athletes where its important to note that the treatment differs for an acute mild sprain which occurs for 4 weeks or less and for a chronic and more severe sprain which extends for more than 4 weeks and during the different healing phases of the injury. [28]

In the case of mild ankle sprain, the goals of physical therapy include decreasing pain and swelling and protecting the joint and its ligaments from further injury. Normally, the duration for a patient to recover ranges between 5 to 14 days. As for the case of chronic ankle sprain, the goals of physical therapy focus on reducing pain and edema and restoring functional movement and stability. Normally, the duration for a patient to recover is 3 to 12 weeks or even more[33].

The common treatment protocol followed is the PRICE (Protect, Rest, Ice, Compress, Elevate) treatment. It involves resting the injured ankle for the first 72 hours and if necessary protecting the ankle joint through the use of crutches then applying ice can help with the swelling and pain and a compress using a bandage or a brace is used to stabilize the joint and finally elevating the ankle can also help with the pain and edema[34].

First time lateral ligament sprains can be innocuous injuries that resolve quickly with minimal intervention and some approaches suggest that only minimal intervention is necessary. The NICE guidelines 2016 recommend advice and analgesia, but not routine physiotherapy referrals[35]. However, it has has also been highlighted that recurrence rate of first time lateral ankle sprains is 70%[36]. With the recurrence rate so high and the guidelines not recommending any rehabilitation, this approach has been questioned[37].

The healing process can be divided in 3 phases and they include inflammatory phase, proliferative phase and the remodeling or maturation phase. The inflammatory phase is the first phase in the healing process. It occurs immediately after an injury and lasts for a period that ranges between 2 to 7 days. The main goals during this phase include the reduction of pain and edema and providing support for the foot[38]. The PRICE protocol is the common treatment protocol during this phase and involves protection of the ankle from further injury by avoiding activities that put the ankle joint at further risk of injury and resting after the injury, applying ice for a minimum of 15 minutes and applying a compression bandage to reduce swelling and edema and finally elevating the ankle to further reduce swelling. Despite its widespread clinical use, the precise physiologic responses to ice application have not been fully elucidated. Moreover, the rationales for its use at different stages of recovery are quite distinct. There is insufficient evidence available from randomized control trials to determine the relative effectiveness of RICE therapy for acute ankle sprains in adults. But no evidence exist to reject the RICE protocol[39]. The use of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs for initial treatment of ankle sprain is supported according to a meta-analysis involving 22 studies[40].

To increase ankle stability and provide support for the ankle joint during the inflammatory phase, active and passive mobilization of the foot and ankle is done to reduce pain and prevent venous stasis and improve local circulation allowing resorption of edema. These mobilization techniques involve subtalar distraction to reduce pain, medial subtalar glide and lateral subtalar glide to increase eversion and inversion[41].

The proliferative phase begins after inflammation has been minimized and lasts for 4 to 6 weeks. During this phase, the scar tissue begins to form adapting the initial physical properties of the tissue before the injury. The goals of physical therapy during this phase includes retrieving ankle function, improving weight bearing capacities on the affected foot and increasing range of motion while protecting the joint from recurrence of the injury. It is important to begin early with the rehabilitation of the ankle. First week exercises produce significant improvements to short term ankle function.[42]

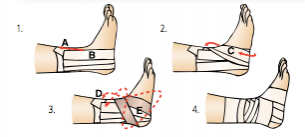

A brace or tape can be applied too as an external fixator at the beginning of this phase to protect the joint. It is applied as soon as swelling decreases and depends on the patient's preference. According to a randomized control trial on 50 patients, results showed that the use of an Aircast ankle brace for the treatment of lateral ligament ankle sprains produces a significant improvement in ankle joint function at both 10 days and one month compared with standard management with an elastic support bandage[43].

Two examples of ankle sprain taping techniques, but there are many other different techniques.

| [44]( | [45](l |

The remodeling and maturation phase is a long-term process and represents the final phase of the healing process. The goals of rehabilitation during this phase involves improving muscle strength, active stability, foot and ankle motion and mobility. In addition to that, improve load-carrying capacity, walking skills and improve the skills needed during activities of daily living as well as work and sports. The rehabilitation program during this phase consists of practicing balance, muscle strength, ankle/foot motion and mobility (walking, stairs, running), looking for a symmetric walk patterns, working on dynamic stability as soon as load -bearing capacity allows, focusing on balance and coordination exercises. Then gradually progress the loading, from static to dynamic exercises, from partially loaded to fully loaded exercises and from simple to functional multi-tasking exercises and use different types of surfaces to increase the level of difficulty. The patient should be encouraged to pursue practicing the exercises given during the sessions at home. The patient is also advised to wear tape or a brace during physical activities until the patient is able to confidently perform static and dynamic balance and motor coordination exercises[46][47].

Return to Activities after Ankle Sprain[edit | edit source]

It is often thought that ankle sprain is a harmless injury, but we have previously seen that it can be the cause of subsequent pathologies such as osteoarthritis or chronic ankle instability.

Some protocols and standardizations for Return To Sport have been used for situations such as post- LCA operation or hamstring injury, but still remains unknown to many subjects. Evidence-based medicine is missing, particularly related to foot injuries and ankle, to assist in the decision to allow an athlete to RTS. Thanks to a recent systematic review by Tessigol et al. we know that there are currently no published evidence-based criteria to inform RTS decisions for patients with an LAS injury. [48]

Even if the literature doesn't help us have the usual bases on a return to sport after ankle sprain, it doesn't mean that athletes are not to be tested.

Tests and Criteria[edit | edit source]

- Ankle Mobility: knee to wall test

- Lower Limb Strength: A typical load level during a single leg vertical jump landing is approximately 1.5 your own weight corporeal [49]; in fact, in order to perform certain dynamic activities, it would be advisable to have capacity to generate force (and absorption) equal to 1.5 times its own body weight. Lee Herrington et al. [50]following the data previously exposed, they introduced the ability to perform 10 reps of single leg press (1.5 times of body weight) as a criterion for return to run after a cruciate ligament injury. While it is not proven for ankle sprain, it can be of great help in returning an athlete to running.

- Static Balance Test: Y balance test

- Dynamic Balance Test: LESS or HOP Test

- Agility Test: Illinois Test, T-test or some sport specific agility test.

Chronic Ankle Instability[edit | edit source]

On-going issues following a lateral ligament injury within the ankle are reported in 19-72% of patients. An ability to complete certain movement tasks, evidence of deficits during the Star Excursion Balance Test and self-reported function as quantified using the Foot and Ankle Ability Measure can be utilised as predictive measures of a Chronic Ankle Instability (CAI) outcome in the clinical setting for patients with a first time lateral ankle sprain injury[51]. Around 20% of people develop CAI and this has been attributed to a delayed muscle reflex of stabilising lower leg muscles, deficits in lower leg muscle strength, deficits in kinaesthesia or impaired postural control[52][53].

Chronic ankle instability has been describes as a combination of mechanical (pathological laxity, arthrokinematic restrictions, and degenerative and synovial changes) and functional (Impaired proprioception and neuromuscular control, and strength deficits) insufficiencies[54]. A sound treatment program must adhere to both mechanical and functional insufficiencies.

It is recommended that all patients undergo conservative treatment to improve stability and improve the muscle reflex and strength of the lower limb stabilising muscles. Although this will help some individuals, it cannot compensate for the defecit of the lateral ligament complex and surgery is occasionally required[52].

Ankle Bracing and Taping[edit | edit source]

Ankle Bracing and taping is often used as a preventative measure which has gained increasing research. Ankle taping may be used to help stabilise the joint by limiting motion and proprioception. Ankle taping is said to have a greater effect in preventing recurrent strains rather than an initial sprain[10]. A study on basketball players detailed the effectiveness of ankle taping on reducing the risk of re-injury in athletes who have a history of ankle-ligament sprains. The large sample size of the study (n=10,393) and identification of 40 ankle injuries adds reliability to the results expressed. Tropp et al, 1985, undertook a study in soccer players who wore an ankle brace. The subjects in the brace group experienced a significant decrease in the incidence of ankle sprains when compared to no intervention[55]. Surve et al, 1994, described similar effects in their prospective study with bracing but noted there was no difference in the ankle sprain severity in the braced and unbraced groups[56].

Reports are inconclusive on the effective of ankle taping. Several reports have suggested the ineffectiveness of taping[10][57]. It’s effectiveness is also affected by the experience of the taper. Some of the advantages of bracing over taping are; cost[58], reusability, no expertise is required for application and minimal effect of an allergic reaction[59].

Resources[edit | edit source]

- The Sprained Ankle from the Connecticut Centre for Orthopedic Surgery contains a range of resources on Ankle Sprains including patient resources and surgical techniques.

Coordinated Health TV Ankle Sprain Video Series

| [60] | [61] | [62] |

Denver-Vail Orthopedics, P.C Ankle Sprain Video Series

| [63] | [64] |

| [65] | [66] |

References[edit | edit source]

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 OrthoInfo. Sprained Ankle. Available from: https://orthoinfo.aaos.org/en/diseases--conditions/sprained-ankle/ (accessed 22/12/2022)

- ↑ Fong DT, Hong Y, Chan LK, Yung PS, Chan KM. A systematic review on ankle injury and ankle sprain in sports. Sports medicine. 2007 Jan;37(1):73-94.

- ↑ Doherty C, Delahunt E, Caulfield B, Hertel J, Ryan J, Bleakley C. The incidence and prevalence of ankle sprain injury: a systematic review and meta-analysis of prospective epidemiological studies. Sports medicine. 2014 Jan;44(1):123-40.

- ↑ Soboroff SH, Pappius EM, KOMAROFF AL. Benefits, risks, and costs of alternative approaches to the evaluation and treatment of severe ankle sprain. Clinical Orthopaedics and Related Research. 1984 Mar 1;183:160-8.

- ↑ Fong DT, Hong Y, Chan LK, Yung PS, Chan KM. A systematic review on ankle injury and ankle sprain in sports. Sports medicine. 2007 Jan;37(1):73-94.

- ↑ Rhon DI, Fraser JJ, Sorensen J, Greenlee TA, Jain T, Cook CE. Delayed Rehabilitation Is Associated With Recurrence and Higher Medical Care Use After Ankle Sprain Injuries in the United States Military Health System. Journal of Orthopaedic & Sports Physical Therapy. 2021 Dec;51(12):619-27.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 Roos KG, Kerr ZY, Mauntel TC, Djoko A, Dompier TP, Wikstrom EA. The epidemiology of lateral ligament complex ankle sprains in National Collegiate Athletic Association sports. The American journal of sports medicine. 2017 Jan;45(1):201-9.

- ↑ Doherty C, Delahunt E, Caulfield B, Hertel J, Ryan J, Bleakley C. The incidence and prevalence of ankle sprain injury: a systematic review and meta-analysis of prospective epidemiological studies. Sports medicine. 2014 Jan;44(1):123-40.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 Yeung MS, Chan KM, So CH, Yuan WY. An epidemiological survey on ankle sprain. British journal of sports medicine. 1994 Jun 1;28(2):112-6.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 10.2 McKay GD, Goldie PA, Payne WR, Oakes BW. Ankle injuries in basketball: injury rate and risk factors. British journal of sports medicine. 2001 Apr 1;35(2):103-8.

- ↑ Marc A Molis MD. Talofibular ligament injury [Internet]. Background, Epidemiology, Functional Anatomy. Medscape. Available from: https://emedicine.medscape.com/article/86396-overview (accessed 22/12/2022)

- ↑ Bauer M, BERGSTRÖM B, HEMBORG A, SANDEGÅRD J. Malleolar Fractures: Nonoperative Versus Operative Treatment A Controlled Study. Clinical Orthopaedics and Related Research.1985 Oct 1;199:17-27.

- ↑ Norkus SA, Floyd RT. The anatomy and mechanisms of syndesmotic ankle sprains. Journal of athletic training. 2001 Jan;36(1):68.

- ↑ Beynnon BD, Murphy DF, Alosa DM. Predictive factors for lateral ankle sprains: a literature review. Journal of athletic training. 2002 Oct;37(4):376.

- ↑ Delahunt E, Remus A. Risk factors for lateral ankle sprains and chronic ankle instability. Journal of athletic training. 2019 Jun;54(6):611-6.

- ↑ Hubbard TJ, Hicks-Little CA. Ankle ligament healing after an acute ankle sprain: an evidence-based approach. Journal of athletic training. 2008 Sep;43(5):523-9.

- ↑ Hubbard TJ, Hicks-Little CA. Ankle ligament healing after an acute ankle sprain: an evidence-based approach. Journal of athletic training. 2008 Sep;43(5):523-9.

- ↑ Moré-Pacheco A, Meyer F, Pacheco I, Candotti CT, Sedrez JA, Loureiro-Chaves RF, Loss JF. Ankle sprain risk factors: a 5-month follow-up study in volley and basketball athletes. Revista Brasileira de Medicina do Esporte. 2019 Jul 1;25:220-5.

- ↑ Knadmin, Tonkin BK, Senk A, Nguyen MV, Patel SC, Kuball PT. Ankle and foot neuropathies & entrapments. PM&R KnowledgeNow. Available from: https://now.aapmr.org/ankle-and-foot-neuropathies-entrapments/ (accessed 22/12/2022)

- ↑ Martin RL, Davenport TE, Fraser JJ, Sawdon-Bea J, Carcia CR, Carroll LA, Kivlan BR, Carreira D. Ankle stability and movement coordination impairments: lateral ankle ligament sprains revision 2021: clinical practice guidelines linked to the international classification of functioning, disability and health from the academy of orthopaedic physical therapy of the American physical therapy association. Journal of Orthopaedic & Sports Physical Therapy. 2021 Apr;51(4):CPG1-80.

- ↑ Knadmin, Tonkin BK, Senk A, Nguyen MV, Patel SC, Kuball PT. Ankle and foot neuropathies & entrapments. PM&R KnowledgeNow. Available from: https://now.aapmr.org/ankle-and-foot-neuropathies-entrapments/ (accessed 23/12/2022)

- ↑ Bachmann LM, Kolb E, Koller MT, Steurer J, ter Riet G. Accuracy of Ottawa ankle rules to exclude fractures of the ankle and mid-foot: systematic review. Bmj. 2003 Feb 22;326(7386):417.

- ↑ Van der Wees PJ, Lenssen AF, Feijts YAEJ, Bloo H, van Moorsel SR, Ouderland R, et al. KNGF-Guideline for Physical Therapy in patients with acute ankle sprain. Dutch J Phys Ther. 2006; 116(Suppl 5):**. Available from: https://www.kngfrichtlijnen.nl/images/imagemanager/guidelines_in_english/KNGF_Guideline_for_Physical_Therapy_in_patients_with_Acute_Ankle_Sprain.pdf (accessed 29 Aug 2012).

- ↑ GP Online (2007). Differential diagnosis of common ankle injuries, Available at: http://www.gponline.com/differential-diagnosis-common-ankle-injuries/article/766219 (Accessed: 24th Aug 2014).

- ↑ 25.0 25.1 Lacerda D, Pacheco D, Rocha AT, Diniz P, Pedro I, Pinto FG. Current concept review: State of acute lateral ankle injury classification systems. The Journal of Foot and Ankle Surgery. 2022;62(1):197–203.

- ↑ Bernstein J. Musculoskeletal Medicine. Rosemont, IL; American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons. 2003. p.242.

- ↑ Gaebler C, Kukla C, Breitenseher MJ, Nellas ZJ, Mittlboeck M, Trattnig S, Vécsei V. Diagnosis of lateral ankle ligament injuries: comparison between talar tilt, MRI and operative findings in 112 athletes. Acta Orthopaedica Scandinavica. 1997 Jan 1;68(3):286-90.

- ↑ 28.0 28.1 Encarnacion T. Ankle sprain. UConn Musculoskeletal Institute. Available from: https://health.uconn.edu/msi/clinical-services/orthopaedic-surgery/foot-ankle-and-podiatry/ankle-sprain/ (accessed 24/12/2022)

- ↑ Sprained ankle. Mayo Clinic. Mayo Foundation for Medical Education and Research. Available from: https://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/sprained-ankle/diagnosis-treatment/drc-20353231 (accessed 24/12/2022)

- ↑ Via Christi. Musculoskeletal Physical Exam: Ankle. Available from: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=QiSm8rz2cmo [last accessed 24/03/2015]

- ↑ Massage Therapy Practise. Ankle Palpation. Available from: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=uI8Z0obhpew [last accessed 24/03/2015]

- ↑ Larkins LW, Baker RT, Baker JG. Physical examination of the ankle: a review of the original orthopedic special test description and scientific validity of common tests for ankle examination. Archives of Rehabilitation Research and Clinical Translation. 2020 Sep 1;2(3):100072.

- ↑ Physical therapy guidelines for lateral ankle sprain. Foot & Ankle Rehab Guidelines. Available from: https://www.massgeneral.org/assets/mgh/pdf/orthopaedics/foot-ankle/pt-guidelines-for-ankle-sprain.pdf (accessed 24/12/2022)

- ↑ Melanson SW, Shuman VL. Acute Ankle Sprain.In: StatPearls. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing. 2022.

- ↑ NICE, 2016. Sprains and Strains. https://cks.nice.org.uk/sprains-and-strains#!scenario [accessed 5 January 2016]

- ↑ Sefton JM, Hicks-Little CA, Hubbard TJ, Clemens MG, Yengo CM, Koceja DM, Cordova ML. Sensorimotor function as a predictor of chronic ankle instability. Clinical Biomechanics. 2009 Jun 30;24(5):451-8.

- ↑ Doherty C, Bleakley C, Hertel J, Caulfield B, Ryan J, Delahunt E. Recovery From a First-Time Lateral Ankle Sprain and the Predictors of Chronic Ankle Instability A Prospective Cohort Analysis. The American journal of sports medicine. 2016 Apr 1;44(4):995-1003

- ↑ Balduini FC, Vegso JJ, Torg JS, Torg E. Management and rehabilitation of ligamentous injuries to the ankle. Sports medicine. 1987 Sep;4(5):364-80.

- ↑ Van Den Bekerom MP, Struijs PA, Blankevoort L, Welling L, Van Dijk CN, Kerkhoffs GM. What is the evidence for rest, ice, compression, and elevation therapy in the treatment of ankle sprains in adults?. Journal of athletic training. 2012;47(4):435-43.

- ↑ van den Bekerom MP, Sjer A, Somford MP, Bulstra GH, Struijs PA, Kerkhoffs GM. Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) for treating acute ankle sprains in adults: benefits outweigh adverse events. Knee Surgery, Sports Traumatology, Arthroscopy. 2015 Aug;23(8):2390-9.

- ↑ Edmond S. Joint Mobilization/Manipulation, Extremity and Spinal Techniques. 3rd Edition. Amsterdam: Elsevier, 2016.

- ↑ Chris M Bleakley et al., Effect of accelerated rehabilitation on function after ankle sprain: randomised controlled trial., BMJ, 2010. Available from: http://www.bmj.com/content/340/bmj.c1964 (Level of evidence 1a)

- ↑ Boyce SH, Quigley MA, Campbell S. Management of ankle sprains: a randomised controlled trial of the treatment of inversion injuries using an elastic support bandage or an Aircast ankle brace. British journal of sports medicine. 2005 Feb 1;39(2):91-6.

- ↑ Finest Physio. Finest Physio: Ankle Taping. Available from: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=d_XlzZMSV8E [last accessed 09/12/12]

- ↑ itherapies. Mulligan Taping Techniques: Inversion Ankle Sprain. Available from: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=TEjKhf-qDJU [last accessed 09/12/12]

- ↑ Stojanović E, Terrence Scanlan A, Radovanović D, Jakovljević V, Faude O. A multicomponent neuromuscular warm-up program reduces lower-extremity injuries in trained basketball players: a cluster randomized controlled trial. The Physician and Sportsmedicine. 2022 Oct 14:1-9.

- ↑ Guy D. When will I feel better? [Internet]. Rose Physical Therapy Group. 2019 [cited 2022Dec26]. Available from: https://rosept.com/blog/when-will-i-feel-better

- ↑ Bruno Tassignon Jo Verschueren Eamonn Delahunt Michelle Smith Bill Vicenzino Evert Verhagen Romain Meeusen Criteria‑Based Return to Sport Decision‑Making Following Lateral Ankle Sprain Injury: a Systematic Review and Narrative Synthesis Sport medicine 2019 Apr;49(4):601-619.doi: 10.1007/s40279-019-01071-3.

- ↑ Cleather, D., Goodwin, J., & Bull, A. Hip and knee joint loading during vertical jumping and push jerking. Clinical Biomechanics 2013 Jan;28(1):98-103. doi: 10.1016/j.clinbiomech.2012.10.006. Epub 2012 Nov 10.

- ↑ Lee Herrington Gregory Myer Ian Horsley Task based rehabilitation protocol for elite athletes following Anterior Cruciate ligament reconstruction: a clinical commentary Phys Ther Sport. 2013 Nov;14(4):188-98. doi: 10.1016/j.ptsp.2013.08.001. Epub 2013 Aug 28.

- ↑ Doherty C, Bleakley C, Hertel J, Caulfield B, Ryan J, Delahunt E. Recovery from a first-time lateral ankle sprain and the predictors of chronic ankle instability: a prospective cohort analysis. The American journal of sports medicine. 2016 Apr;44(4):995-1003.

- ↑ 52.0 52.1 Al-Mohrej OA, Al-Kenani NS. Chronic ankle instability: Current perspectives. Avicenna journal of medicine. 2016 Oct;6(4):103.

- ↑ Eechaute C, Vaes P, Van Aerschot L, Asman S, Duquet W. The clinimetric qualities of patient-assessed instruments for measuring chronic ankle instability: a systematic review. BMC musculoskeletal disorders. 2007 Jan 18;8(1):1.

- ↑ Hertel, J. (2002). Functional anatomy, pathomechanics, and pathophysiology of lateral ankle instability. Journal of athletic training, 37(4), 364.

- ↑ Tropp H, Ekstrand J, Gillquist J. Stabilometry in functional instability of the ankle and its value in predicting injury. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 1984;16:64–66.

- ↑ Surve I, Schwellnus MP, Noakes T, Lombard C. A fivefold reduction in the incidence of recurrent ankle sprains in soccer players using the Sport- Stirrup orthosis. Am J Sports Med. 1994;22:601–606.

- ↑ Rovere, G. D., Clarke, T. J., Yates, C. S., & Burley, K. (1988). Retrospective comparison of taping and ankle stabilizers in preventing ankle injuries. The American journal of sports medicine, 16(3), 228-233.

- ↑ Olmsted, L. C., Vela, L. I., Denegar, C. R., & Hertel, J. (2004). Prophylactic ankle taping and bracing: a numbers-needed-to-treat and cost-benefit analysis. Journal of athletic training, 39(1), 95.

- ↑ Callaghan, M. J. (1997). Role of ankle taping and bracing in the athlete. British journal of sports medicine, 31(2), 102-108.

- ↑ Coordinated Health TV. Ankle Sprains Part 1: Anatomy. Available from: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=PDFbZFNtPfs[last accessed 24/03/2015]

- ↑ Coordinated Health TV. Ankle Sprains Part 2: Symptoms & Evaluation. Available from: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=dP17ZY3zxa4 [last accessed 24/03/2015]

- ↑ Coordinated Health TV. Ankle Sprains Part 3: Rehab & Protection. Available from: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=dznWBbwLq6k[last accessed 24/03/2015]

- ↑ Denver-Vail Orthopedics. Ankle Sprains Part 1 How they occur, what ligaments are injured and initial treatment. Available from: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=B0-n-ndTAX0[last accessed 24/03/2015]

- ↑ Denver-Vail Orthopedics. Ankle Sprains Part 2 Stretching and Range of Motion Exercises. Available from: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=YHJbvf4TW2Y[last accessed 24/03/2015]

- ↑ Denver-Vail Orthopedics. Ankle Sprains Part 3 Stretching and Range of Motion Exercises. Available from: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=u6xRWb9dFbU[last accessed 24/03/2015]

- ↑ Denver-Vail Orthopedics. Ankle Sprains Part 4 Proprioception - Balance. Available from: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=AsEV5OYghSQ[last accessed 24/03/2015]