Hyperalgesia: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

(corrected cite error) |

||

| (8 intermediate revisions by 4 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

<div class="editorbox"> | <div class="editorbox"> | ||

'''Original Editor '''- [[User: | '''Original Editor '''- [[User:Melissa Coetsee |Melissa Coetsee ]] | ||

'''Top Contributors''' - {{Special:Contributors/{{FULLPAGENAME}}}} | '''Top Contributors''' - {{Special:Contributors/{{FULLPAGENAME}}}} | ||

| Line 9: | Line 7: | ||

IASP definition: | IASP definition: | ||

<blockquote>"Increased pain from a stimulus that normally provokes pain."<ref name=":0">IASP. Terminology. Available from: https://www.iasp-pain.org/resources/terminology/ (accessed 12 Dec 2023)</ref> </blockquote>Hyperalgesia is a clinical term used to described the phenomenon of an increased pain response to a painful stimuli (such as pin prick, pressure, extreme heat/cold). It does not imply a single pain mechanism, but is associated with [[Peripheral Sensitisation|peripheral sensitisation]] and [[Central Sensitisation|central sensitisation]].<ref name=":0" /> | <blockquote>"Increased pain from a stimulus that normally provokes pain."<ref name=":0">IASP. Terminology. Available from: https://www.iasp-pain.org/resources/terminology/ (accessed 12 Dec 2023)</ref> </blockquote>Hyperalgesia is a clinical term used to described the phenomenon of an increased pain response to a painful stimuli (such as pin prick, deep pressure, extreme heat/cold). It does not imply a single pain mechanism, but is associated with [[Peripheral Sensitisation|peripheral sensitisation]] and [[Central Sensitisation|central sensitisation]].<ref name=":0" /> | ||

Hyperalgesia is normal protective response after tissue damage and will usually subside as healing occurs.<ref name=":1">Sandkuhler J. | Hyperalgesia is normal protective response after tissue damage and will usually subside as healing occurs.<ref name=":1">Sandkuhler J. Models and mechanisms of hyperalgesia and allodynia. Physiological reviews. 2009 Apr;89(2):707-58.</ref> It may however increase over time in certain conditions, such as [[Neuropathic Pain|neuropathic pain]] conditions, and may be present in the absence of tissue injury. | ||

==Aetiology/Mechanism== | ==Aetiology/Mechanism== | ||

Hyperalgesia may involve a reduction in nociceptive firing threshold, and an increase in the supra-threshold response.<ref name=":1" />The end result is amplified nociception and an increase in pain intensity. | Hyperalgesia may involve a reduction in nociceptive firing threshold, and an increase in the supra-threshold response.<ref name=":1" />The end result is amplified [[nociception]] and an increase in pain intensity. | ||

* '''Primary Hyperalgesia:''' Hyperalgesia that occurs at the site of injury and is often a reflection of [[Peripheral Sensitisation|peripheral sensitisation]]. It occurs as a result of reduced activation threshold and increased responsiveness of nociceptors.<ref name=":1" /> | * '''Primary Hyperalgesia:''' Hyperalgesia that occurs at the site of injury and is often a reflection of [[Peripheral Sensitisation|peripheral sensitisation]]. It occurs as a result of reduced activation threshold and increased responsiveness of nociceptors (A-delta and C-fibres).<ref name=":1" /> | ||

* '''Secondary Hyperalgesia:''' Hyperalgesia in an area adjacent to or remote from the site of injury.<ref name=":1" /> | * '''Secondary Hyperalgesia:''' Hyperalgesia in an area adjacent to or remote from the site of injury.<ref name=":1" />It is maintained by changes in the central processing of sensory information, including sensitisation of the spinal nociceptive neurons and altered descending inhibition.<ref name=":1" />Secondary hyperalgesia reflects that [[Central Sensitisation|central sensitisation]] (at spinal cord/brain level) is at play. It involves sensitisation of second-order neurons in the dorsal horn, as well as activation of nociceptive neurons in the brainstem and thalamus.<ref name=":5">McClan BC,Chapter 5: Primary and Secondary Hyperalgesia. In: Sinatra RS, Jahr JS, Watkins-Pitchford JM. The Essence of Analgesia and Analgesics. New York. Cambridge University Press. 2011. p17-19</ref> | ||

It is important to remember, that in acute injuries, the finding of hyperalgesia is a normal adaptive response. Since the injured tissue is vulnerable, the nociceptive system adapts by becoming sensitised to ensure tissue protection.<ref name=":1" />In such a case hyperalgesia would be an appropriate shift in pain threshold. It is however possible for this normal response to be exaggerated and does not always reflect the severity of an injury. | It is important to remember, that in acute injuries, the finding of hyperalgesia is a normal adaptive response. Since the injured tissue is vulnerable, the nociceptive system adapts by becoming sensitised to ensure tissue protection.<ref name=":1" />In such a case hyperalgesia would be an appropriate shift in pain threshold. It is however possible for this normal response to be exaggerated and does not always reflect the severity of an injury. | ||

If hyperalgesia does however occur long after tissue healing has occurred or in the absence of damaged tissue, it is considered maladaptive. | If hyperalgesia does however occur long after tissue healing has occurred or in the absence of damaged tissue, it is considered maladaptive and may indicate nerve damage, ongoing nociception and/or sensitisation and can contribute to chronic pain states. Persistent tissue injury and inflammation can also result in ongoing hyperalgesia.<ref name=":5" /> | ||

=== Nerve Sensitisation === | |||

As mentioned above, hyperalgesia occurs as a result of nociceptive sensitisation. The following mechanisms cause nerve sensitisation<ref name=":2">Train Pain Academy. Principles of Pain (Module 1) - handout. 2017.</ref>: | |||

* [[Neurogenic Inflammation]]: Peripheral nociceptors participate in the inflammatory process by releasing neuropeptides (like Substance P) | |||

* Inflammatory mediators (histamine, prostaglandin, bradykinin, cytokines) | |||

* [[Glial Cells|Glial cells]] can release proinflammatory [[cytokines]] | |||

* Change in pH associated with inflammation | |||

=== Risk Factors === | === Risk Factors === | ||

The following factors may increase the risk of maladaptive hyperalgesia: | The following factors may increase the risk of maladaptive hyperalgesia: | ||

* ''' | * '''Chronic [[Inflammation Acute and Chronic|Inflammation]]:''' Excess fat results in chronic release of inflammatory mediators which could increase nociceptive sensitisation | ||

* ''' | * '''Immune response:''' When an injury occurs while the immune system is active (eg. fighting an acquired infection), exaggerated hyperalgesia is more likely since nociceptors are already sensitised<ref name=":2" /> | ||

* | * '''Stress:''' Pain pathways are modulated by stress, and exposure to chronic stress can produce maladaptive changes in pain processing leading to stress-induced hyperalgesia. <ref>Jennings EM, Okine BN, Roche M, Finn DP. [https://aran.library.nuigalway.ie/bitstream/handle/10379/15079/Manuscript_text_Combined_Files.pdf Stress-induced hyperalgesia.] Progress in neurobiology. 2014 Oct 1;121:1-8.</ref> <ref name=":1" /> | ||

* '''[[Opioids|Opioid]] use:''' Opioid-induced hyperalgesia occurs when opioids paradoxically enhance pain. This can occur with acute or chronic exposure to opioids. [[Opioid Use Disorder|Opioid tolerance]] and withdrawal can also affect pain sensitivity as it affects descending pain modulation. <ref>Wilson SH, Hellman KM, James D, Adler AC, Chandrakantan A. Mechanisms, diagnosis, prevention and management of perioperative opioid-induced hyperalgesia. Pain Management. 2021 Jul;11(4):405-17.</ref> | |||

== Conditions == | == Conditions == | ||

Listed below are some conditions that may present with ongoing hyperalgesia: | |||

* [[Neuropathic Pain]]: primary and secondary hyperalgesia<ref name=":3">Arendt‐Nielsen L, Morlion B, Perrot S, Dahan A, Dickenson A, Kress HG, Wells C, Bouhassira D, Drewes AM. Assessment and manifestation of central sensitisation across different chronic pain conditions. European Journal of Pain. 2018 Feb;22(2):216-41.</ref> | |||

* Postherpetic Neuralgia: primary hyperalgesia<ref name=":3" /> | |||

* [[Neuropathies]] | |||

* Polyneuropathy such as [[HIV-related Neuropathy]] and Diabetic Neuropathy | |||

* [[Brachial Plexus Injury]] | |||

* [[Fibromyalgia]]<ref name=":4">Jensen TS, Finnerup NB. A[https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1474442214701024| llodynia and hyperalgesia in neuropathic pain: clinical manifestations and mechanisms.] The Lancet Neurology. 2014 Sep 1;13(9):924-35.</ref> | |||

* [[Irritable Bowel Syndrome]]<ref name=":3" /> | |||

* [[Chemotherapy-Induced Peripheral Neuropathy (CIPN)|Chemotherapy induced peripheral neuropathy]] | |||

* [[Central Sensitisation]] | |||

* [[Peripheral Sensitisation]] | |||

* [[Complex Regional Pain Syndrome (CRPS)]] | |||

* [[Chronic Low Back Pain]]<ref name=":3" /> | |||

* [[Osteoarthritis]]<ref name=":3" /> | |||

* [[Rheumatoid Arthritis]] | |||

* [[Amputation Pain Rehabilitation|Post-amputation stump pain]] | |||

* Central nervous system disorders: [[Post-Stroke Pain|Post-stroke pain]], [[Multiple Sclerosis (MS)|Multiple Sclerosis]], [[Spinal Cord Injury]]<ref name=":4" /> | |||

== Differential Diagnosis == | == Differential Diagnosis == | ||

[[File:Allodynia.png|thumb|Hyperalgesia vs Allodynia]] | |||

Another clinical term that needs to be differentiated from hyperalgesia, is [[allodynia]]. Where hyperalgesia refers to changes in the '''intensity''' of the sensation of pain, allodynia refers to changes in the '''quality''' of sensation. | |||

Allodynia occurs when non-nociceptive afferents become sensitised, which results in non-painful stimuli becoming painful. Hyperalgesia involves sensitisation of nociceptors altering the intensity of pain for given painful stimulus. | |||

Although allodynia and hyperalgesia are distinct clinical terms, they can and often do co-exist. | |||

==Assessment== | ==Assessment== | ||

Hyperalgesia to various painful stimuli can be assessed, and forms part of [[Quantitative Sensory Testing (QST)|Quantitative Sensory Testing]] (QST). | |||

* Hyperalgesia to various painful stimuli can be assessed, and forms part of [[Quantitative Sensory Testing (QST)|'''Quantitative Sensory Testing''']] (QST). QST is a way to evaluate the excitability of different pain pathways and can provide valuable insight into pain mechanisms.<ref name=":3" /> | |||

* Always compare to the unaffected side or a body site distant from the affected area (especially if there is bilateral involvement) | |||

* Mental health screening for [[depression]] and/or anxiety | |||

* History of chronic medication and other conditions which could contribute to hyperalgesia (eg. [[neuropathies]], [[diabetes]], [[HIV/AIDS|HIV]], chemotherapy, stroke) | |||

* Full neurological examination to assess for nerve damage and neuropathic pain (including sensation, reflexes and muscle power). | |||

== Treatment == | == Treatment == | ||

'''Acute injuries''' | '''Acute injuries''' | ||

* The focus is to minimise the development of sustained hyperalgesia | * The focus is to minimise the development of sustained/chronic hyperalgesia. Pain needs to be addressed early to '''prevent ongoing nociception''' | ||

* '''Control excessive inflammation''' with rest, anti-inflammatories and ice | |||

* It may be necessary to '''temporarily immobilise'''/brace the affected joint and adjust '''weight bearing status''' to ensure minimal ongoing nociception | |||

* Once inflammation has settled, fear of movement needs to be addressed/prevented by encouraging and guiding '''graded movement and loading''' | |||

* Psychologically informed '''communication''' is very important. Instilling unnecessary fear and negative expectations by using negative language (eg. "your ankle is pretty messed up" or "this is the worst sprain I've seen") can actually have a nocebo effect and negatively influence descending inhibition. Realistic caution and prognosis should be shared using safe and non-threatening language.<ref name=":6">Rodrigues BA, Silva LM, Lucena HÍ, Morais EP, Rocha AC, Alves GA, Benevides SD. N[https://www.scielo.br/j/rcefac/a/zRy6W7P67csTLjt8wqtdv8f/?format=pdf&lang=en ocebo effect in health communication: how to minimize it?]. Revista CEFAC. 2022 Nov 21;24.</ref> | |||

* Address false beliefs and help the patient to process any fears related to the injury | |||

* See the [[Peace and Love Principle|PEACE and LOVE]] acute injury protocol | |||

'''Chronic pain''' | '''Chronic pain''' | ||

== | * See the page on [[Neuropathic Pain|'''Neuropathic pain''']] and '''[[Neuropathic Pain Medication|Neuropathic medication]]''' for hyperalgesia related to nerve lesions. | ||

* | * Avoid negative language in chronic conditions (eg. "bone on bone", "degenerative") to minimise the nocebo effect.<ref name=":6" /> | ||

* | * Use positive '''communication''' strategies to address false beliefs and fears. These include [[Motivational Interviewing|motivational interviewing]], positive framing, [[Using Empathy in Communication|empathetic communication]].<ref name=":6" /> | ||

or | * [[Pain Neuroscience Education (PNE)|Pain Neuroscience Education]] (PNE) | ||

* '''Psychosocial interventions:''' Counselling may be recommended if signs of depression are detected. [[Biofeedback]], [[mindfulness]] training, and [[Cognitive Behavioural Therapy|cognitive behavioural therapy]] can influence descending inhibition and therefore alter pain perception. | |||

* [[Graded Motor Imagery]] - especially in [[Complex Regional Pain Syndrome (CRPS)|CRPS]] | |||

* Ice and [[NSAIDs]] can be effective in controlling chronic or [[Neurogenic inflammation in Musculoskeletal Condition|neurogenic inflammation]] | |||

* [[Transcutaneous Electrical Nerve Stimulation (TENS)|Transcutaneous Electrical Nerve Stimulation]] (TENS) may reduce chronic inflammatory hyperalgesia. It may be necessary to apply TENS on areas remote from the painful area if the painful area is to sensitive.<ref>DeSantana JM, Walsh DM, Vance C, Rakel BA, Sluka KA. [https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2746624/ Effectiveness of transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation for treatment of hyperalgesia and pain.] Current rheumatology reports. 2008 Dec;10(6):492-9.</ref> | |||

* Graded exposure to movement: Avoid "pushing through" the pain, and encourage pacing and gradually increase loading | |||

==Conclusion== | |||

Hyperalgesia is a phenomenon that is continually being researched and interpretation of this clinical sign may change as research evolves. It is important to assess hyperalgesia early on and careful assessment of various biological and psychological mechanisms are required to ensure targeted treatment strategies. Hyperalgesia is normal in acute injuries, but also plays a role in the development of chronic pain states. | |||

==References== | ==References== | ||

<references /> | <references /> | ||

[[Category:Conditions]] | |||

[[Category:Pain]] | |||

[[Category:Neuropathy]] | |||

Latest revision as of 14:05, 19 March 2024

Original Editor - Melissa Coetsee

Top Contributors - Melissa Coetsee, Kim Jackson, Vidya Acharya and Carina Therese Magtibay

Introduction[edit | edit source]

IASP definition:

"Increased pain from a stimulus that normally provokes pain."[1]

Hyperalgesia is a clinical term used to described the phenomenon of an increased pain response to a painful stimuli (such as pin prick, deep pressure, extreme heat/cold). It does not imply a single pain mechanism, but is associated with peripheral sensitisation and central sensitisation.[1]

Hyperalgesia is normal protective response after tissue damage and will usually subside as healing occurs.[2] It may however increase over time in certain conditions, such as neuropathic pain conditions, and may be present in the absence of tissue injury.

Aetiology/Mechanism[edit | edit source]

Hyperalgesia may involve a reduction in nociceptive firing threshold, and an increase in the supra-threshold response.[2]The end result is amplified nociception and an increase in pain intensity.

- Primary Hyperalgesia: Hyperalgesia that occurs at the site of injury and is often a reflection of peripheral sensitisation. It occurs as a result of reduced activation threshold and increased responsiveness of nociceptors (A-delta and C-fibres).[2]

- Secondary Hyperalgesia: Hyperalgesia in an area adjacent to or remote from the site of injury.[2]It is maintained by changes in the central processing of sensory information, including sensitisation of the spinal nociceptive neurons and altered descending inhibition.[2]Secondary hyperalgesia reflects that central sensitisation (at spinal cord/brain level) is at play. It involves sensitisation of second-order neurons in the dorsal horn, as well as activation of nociceptive neurons in the brainstem and thalamus.[3]

It is important to remember, that in acute injuries, the finding of hyperalgesia is a normal adaptive response. Since the injured tissue is vulnerable, the nociceptive system adapts by becoming sensitised to ensure tissue protection.[2]In such a case hyperalgesia would be an appropriate shift in pain threshold. It is however possible for this normal response to be exaggerated and does not always reflect the severity of an injury.

If hyperalgesia does however occur long after tissue healing has occurred or in the absence of damaged tissue, it is considered maladaptive and may indicate nerve damage, ongoing nociception and/or sensitisation and can contribute to chronic pain states. Persistent tissue injury and inflammation can also result in ongoing hyperalgesia.[3]

Nerve Sensitisation[edit | edit source]

As mentioned above, hyperalgesia occurs as a result of nociceptive sensitisation. The following mechanisms cause nerve sensitisation[4]:

- Neurogenic Inflammation: Peripheral nociceptors participate in the inflammatory process by releasing neuropeptides (like Substance P)

- Inflammatory mediators (histamine, prostaglandin, bradykinin, cytokines)

- Glial cells can release proinflammatory cytokines

- Change in pH associated with inflammation

Risk Factors[edit | edit source]

The following factors may increase the risk of maladaptive hyperalgesia:

- Chronic Inflammation: Excess fat results in chronic release of inflammatory mediators which could increase nociceptive sensitisation

- Immune response: When an injury occurs while the immune system is active (eg. fighting an acquired infection), exaggerated hyperalgesia is more likely since nociceptors are already sensitised[4]

- Stress: Pain pathways are modulated by stress, and exposure to chronic stress can produce maladaptive changes in pain processing leading to stress-induced hyperalgesia. [5] [2]

- Opioid use: Opioid-induced hyperalgesia occurs when opioids paradoxically enhance pain. This can occur with acute or chronic exposure to opioids. Opioid tolerance and withdrawal can also affect pain sensitivity as it affects descending pain modulation. [6]

Conditions[edit | edit source]

Listed below are some conditions that may present with ongoing hyperalgesia:

- Neuropathic Pain: primary and secondary hyperalgesia[7]

- Postherpetic Neuralgia: primary hyperalgesia[7]

- Neuropathies

- Polyneuropathy such as HIV-related Neuropathy and Diabetic Neuropathy

- Brachial Plexus Injury

- Fibromyalgia[8]

- Irritable Bowel Syndrome[7]

- Chemotherapy induced peripheral neuropathy

- Central Sensitisation

- Peripheral Sensitisation

- Complex Regional Pain Syndrome (CRPS)

- Chronic Low Back Pain[7]

- Osteoarthritis[7]

- Rheumatoid Arthritis

- Post-amputation stump pain

- Central nervous system disorders: Post-stroke pain, Multiple Sclerosis, Spinal Cord Injury[8]

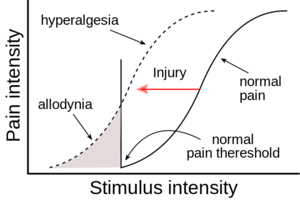

Differential Diagnosis[edit | edit source]

Another clinical term that needs to be differentiated from hyperalgesia, is allodynia. Where hyperalgesia refers to changes in the intensity of the sensation of pain, allodynia refers to changes in the quality of sensation.

Allodynia occurs when non-nociceptive afferents become sensitised, which results in non-painful stimuli becoming painful. Hyperalgesia involves sensitisation of nociceptors altering the intensity of pain for given painful stimulus.

Although allodynia and hyperalgesia are distinct clinical terms, they can and often do co-exist.

Assessment[edit | edit source]

- Hyperalgesia to various painful stimuli can be assessed, and forms part of Quantitative Sensory Testing (QST). QST is a way to evaluate the excitability of different pain pathways and can provide valuable insight into pain mechanisms.[7]

- Always compare to the unaffected side or a body site distant from the affected area (especially if there is bilateral involvement)

- Mental health screening for depression and/or anxiety

- History of chronic medication and other conditions which could contribute to hyperalgesia (eg. neuropathies, diabetes, HIV, chemotherapy, stroke)

- Full neurological examination to assess for nerve damage and neuropathic pain (including sensation, reflexes and muscle power).

Treatment[edit | edit source]

Acute injuries

- The focus is to minimise the development of sustained/chronic hyperalgesia. Pain needs to be addressed early to prevent ongoing nociception

- Control excessive inflammation with rest, anti-inflammatories and ice

- It may be necessary to temporarily immobilise/brace the affected joint and adjust weight bearing status to ensure minimal ongoing nociception

- Once inflammation has settled, fear of movement needs to be addressed/prevented by encouraging and guiding graded movement and loading

- Psychologically informed communication is very important. Instilling unnecessary fear and negative expectations by using negative language (eg. "your ankle is pretty messed up" or "this is the worst sprain I've seen") can actually have a nocebo effect and negatively influence descending inhibition. Realistic caution and prognosis should be shared using safe and non-threatening language.[9]

- Address false beliefs and help the patient to process any fears related to the injury

- See the PEACE and LOVE acute injury protocol

Chronic pain

- See the page on Neuropathic pain and Neuropathic medication for hyperalgesia related to nerve lesions.

- Avoid negative language in chronic conditions (eg. "bone on bone", "degenerative") to minimise the nocebo effect.[9]

- Use positive communication strategies to address false beliefs and fears. These include motivational interviewing, positive framing, empathetic communication.[9]

- Pain Neuroscience Education (PNE)

- Psychosocial interventions: Counselling may be recommended if signs of depression are detected. Biofeedback, mindfulness training, and cognitive behavioural therapy can influence descending inhibition and therefore alter pain perception.

- Graded Motor Imagery - especially in CRPS

- Ice and NSAIDs can be effective in controlling chronic or neurogenic inflammation

- Transcutaneous Electrical Nerve Stimulation (TENS) may reduce chronic inflammatory hyperalgesia. It may be necessary to apply TENS on areas remote from the painful area if the painful area is to sensitive.[10]

- Graded exposure to movement: Avoid "pushing through" the pain, and encourage pacing and gradually increase loading

Conclusion[edit | edit source]

Hyperalgesia is a phenomenon that is continually being researched and interpretation of this clinical sign may change as research evolves. It is important to assess hyperalgesia early on and careful assessment of various biological and psychological mechanisms are required to ensure targeted treatment strategies. Hyperalgesia is normal in acute injuries, but also plays a role in the development of chronic pain states.

References[edit | edit source]

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 IASP. Terminology. Available from: https://www.iasp-pain.org/resources/terminology/ (accessed 12 Dec 2023)

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 2.4 2.5 2.6 Sandkuhler J. Models and mechanisms of hyperalgesia and allodynia. Physiological reviews. 2009 Apr;89(2):707-58.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 McClan BC,Chapter 5: Primary and Secondary Hyperalgesia. In: Sinatra RS, Jahr JS, Watkins-Pitchford JM. The Essence of Analgesia and Analgesics. New York. Cambridge University Press. 2011. p17-19

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 Train Pain Academy. Principles of Pain (Module 1) - handout. 2017.

- ↑ Jennings EM, Okine BN, Roche M, Finn DP. Stress-induced hyperalgesia. Progress in neurobiology. 2014 Oct 1;121:1-8.

- ↑ Wilson SH, Hellman KM, James D, Adler AC, Chandrakantan A. Mechanisms, diagnosis, prevention and management of perioperative opioid-induced hyperalgesia. Pain Management. 2021 Jul;11(4):405-17.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 7.3 7.4 7.5 Arendt‐Nielsen L, Morlion B, Perrot S, Dahan A, Dickenson A, Kress HG, Wells C, Bouhassira D, Drewes AM. Assessment and manifestation of central sensitisation across different chronic pain conditions. European Journal of Pain. 2018 Feb;22(2):216-41.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 Jensen TS, Finnerup NB. Allodynia and hyperalgesia in neuropathic pain: clinical manifestations and mechanisms. The Lancet Neurology. 2014 Sep 1;13(9):924-35.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 9.2 Rodrigues BA, Silva LM, Lucena HÍ, Morais EP, Rocha AC, Alves GA, Benevides SD. Nocebo effect in health communication: how to minimize it?. Revista CEFAC. 2022 Nov 21;24.

- ↑ DeSantana JM, Walsh DM, Vance C, Rakel BA, Sluka KA. Effectiveness of transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation for treatment of hyperalgesia and pain. Current rheumatology reports. 2008 Dec;10(6):492-9.