Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV)

Original Editors - Holly Grant, Justin Klenke & Conner Zuber from Bellarmine University's Pathophysiology of Complex Patient Problems project.

Top Contributors - Holly Grant, Conner Zuber, Kim Jackson, Justin Klenke, Admin, Lucinda hampton, Vidya Acharya, Elaine Lonnemann, Gayatri Jadav Upadhyay, Ajay Upadhyay, Tarina van der Stockt, WikiSysop, 127.0.0.1, Nupur Smit Shah, Wendy Walker, Naomi O'Reilly, Simisola Ajeyalemi and Karen Wilson

Introduction[edit | edit source]

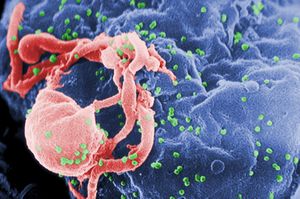

The human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) is an enveloped retrovirus that contains 2 copies of a single-stranded RNA genome. Over time HIV causes acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS), the last stage of HIV disease, a condition in which there is progressive failure of the immune system leading to life-threatening opportunistic infections[1].

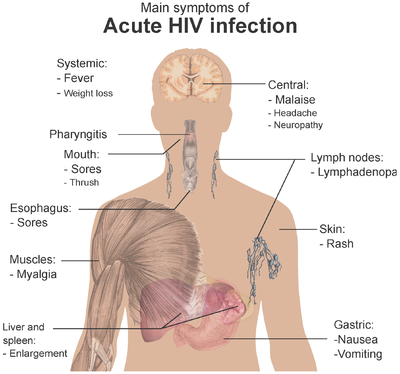

Symptoms do not appear immediately and it can be between Four to 10 weeks after the HIV enters the body, that the first symptoms of primary infection are experienced. After the initial primary infection, a long chronic HIV infection occurs, which can last for decades.

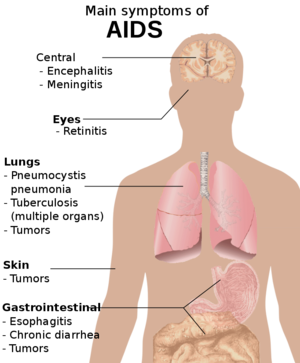

AIDS is mainly characterized by opportunistic infections and tumours ( as a result of immunodeficiency) which are usually fatal without treatment.[2]

To learn more about the stages of HIV visit this Physiopedia page.

Etiology[edit | edit source]

The first cases of acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS) were first reported in the United States in 1981[3] but there are reports that the virus was first found in humans in Central Africa in 1920[4]

The cause of this infectious disease is the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), an RNA virus of the Retroviridae family, can be classified into HIV-1 and HIV-2.

- HIV-1 is more globally expanded and virulent. It originated in Central Africa.

- HIV-2 is much less virulent and comes from West Africa.

- Both viruses are related antigenically to immunodeficiency viruses found primarily in primates.[2]

Epidemiology[edit | edit source]

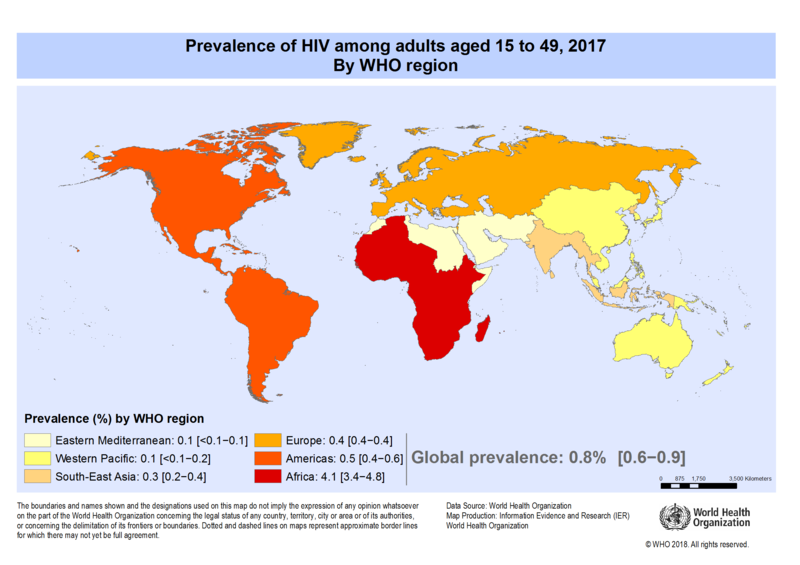

With improved access to effective HIV prevention, diagnosis, treatment and care HIV infection people are now healthier and living longer. This has resulted in many countries seeing a decrease in the incidence of HIV and AIDS, although it still continues to be a major global public health issue. In 2020, there were an estimated 37.7 million people living with HIV. Of these 36.0 million were adults and 1.7 million children aged between the ages of 0–14 years. 53% of these people living with HIV were women and girls.[5] Between 2000 and 2018, new HIV infections decreased by 37% and HIV-related deaths by 45%, with 13.6 million lives saved due to ART. [6]

While efforts in developed countries have led to improvements in mortality, quality of life, and transmission rates; the incidence of HIV and AIDS is drastically different across the globe. For example, in sub-Sarahan Africa, there are an estimated 25 million people of all ages living with HIV. At this time no vaccine exists for HIV.[7]

According to the CDC, at the end of 2016,

- 1.1 million people in the United States were living with HIV/AIDS (approx. 14% do not know they are infected).

- HIV infection is the 5th leading cause of death for people who are between the ages of 25-44 years old in the United States.

- The prevalence of HIV is increased in African American males, male to male sexual relations, and age 25-34.

- The prevalence is 5 times greater in incarcerated populations than the general population at large.

- The high HIV transmission rates among inmates maybe related to homosexual encounters and potentially tattooing.

- Ethnicity is not directly related to AIDS risk, but it is associated with other determinants of health status such as poverty, illegal drug use, access to health care, and living in communities with a high prevalence of AIDS. [8]

- In the United States, a critical risk factor for the HIV propagation among young people is the use of drugs before having sex.

- Other risk factors associated with a risk of acquiring HIV infection include unsafe sexual practices, the use of intravenous drugs, and unsafe blood transfusions or blood products.[2]

Pathophysiology[edit | edit source]

HIV is a bloodborne pathogen that is spread across mucus membranes. The HIV attaches to CD4 molecule and CCR5 (a chemokine co-receptor), the virus surface fuses with the cellular membrane which allows it entry into a T-helper lymphocyte. After integrating with the host genome the HIV provirus forms followed by transcription and the production of viral mRNAs. The HIV structural proteins are assembled in the host cell which then continues to infect other cells.[2]. The main modes of transmission are:

- Unprotected penetrative sex between men

- Unprotected heterosexual intercourse

- Injection drug use

- Unsafe blood and blood by-products

- Mother to child transmission during pregnancy, birth or breast feeding

Staging[edit | edit source]

- Patients with HIV and a CD4 counts greater than 200, but less than 500 do not have AIDS but can develop chronic infections as well as noninfectious conditions. Diseases such as chronic candidiasis of the mouth or recurrent vaginal candida may occur. Patients may develop severe bouts of herpes simplex or herpes zoster (shingles). Patients are also at a higher risk for cancers that are much more difficult to treat than in healthy people.

- Patients with normal CD4 counts (greater than 500) tend to have a good quality of life with a lifespan within 4 years of someone without HIV

- Patients with a CD4 count less than 200 have AIDS and are susceptible to opportunistic infections. They usually have a lifespan of 2 years if they are started on HAART. If these patients are treated with antiretroviral agents and achieve a CD4 count greater than 500, they will have a normal life expectancy.[7]

History and Physical[edit | edit source]

Primary infection occurs 4 to 10 weeks after unprotected sexual practice with an HIV-infected person. The primary HIV infection is characterized by the following symptoms:

- Fever

- Joint pain

- Skin rash

- Sore throat

- Swollen lymph nodes

Chronic HIV infection is characterized by the following signs and symptoms and can last for decades:

- Fever

- Fatigue

- Diarrhea

- Weight loss

- Oral thrush

- Shingles

- Persistent generalized lymphadenopath

Medications[edit | edit source]

Antiretrovirals are drugs used to treat HIV infections/AIDS, and they are used in various combinations commonly referred to as highly active retroviral therapy (HAART).

- The antiretrovirals agent include nucleoside/nucleotide reverse transcriptase inhibitors (NRTIs), NRTI fixed-dose combinations, integrase inhibitors, non-nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors (NNRTIs), protease inhibitors and CCR5 inhibitors.

- All patients with HIV regardless of what level of CD4 should be started on HAART, which is a treatment for life.

- This therapy has been shown to reduce morbidity and mortality plus lower the risk of transmitting the infection to others, as long as the individual has low or undetectable viral load.

No drug/treatment can cure HIV/AIDS, many of the drugs used have side effects that can be severe, and most drug therapies are expensive.

Side Effects of Medication

- Short Term: Rash Anaemia Diarrhoea Nausea Headaches Dizziness Muscle pain Weakness Fatigue Insomnia

- Long Term: Lipodystrophy- a problem in the way the body produces, uses, and stores fat Insulin Resistance Lipid Abnormalities Decrease in bone density Lactic Acidosis

- Hepatotoxicity is also a common complication. [9]

For complete description of HIV drugs, including brand names, see AIDSmeds.com's Treatment for HIV and AIDS. [10]

Diagnostic Tests[edit | edit source]

Early diagnosis is important so that early preventative therapies may be initiated, and sex partners can be notified of their risk of HIV.

HIV infection can remain undetected for years. However, they are several tests to diagnose it[2]:

- Fourth generation assay: Detect specific antibodies and P24 HIV antigens

- Rapid test: Use blood or saliva to detect an HIV infection within hours (The U.S. Food and Drug Administration approved the first rapid HIV test in August 2013[9]).

- Polymerase-chain-reaction: Can be a diagnostic or a confirmative test for HIV infection and can provide information of the viral load

Complications[edit | edit source]

Complication of HIV disease is its progression to acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS). The physician should suspect it once opportunistic infections and/or low CD4 count are present in an individual who is HIV positive.

AIDS occurs when lymphocyte count falls below a level (less than 200 cells per microliters) and is characterized by one or more of the following:[2]

- Tuberculosis (TB)

- Cytomegalovirus

- Candidiasis

- Cryptococcal meningitis

- Cryptosporidiosis

- Toxoplasmosis

- Kaposi's sarcoma

- Lymphoma

- Neurological complications (AIDS dementia complex)

- Kidney disease

Medical Management[edit | edit source]

The management of the patient with HIV or AIDS is complex and lifelong. Collaboration amongst primary care physicians and specialty trained providers such as infectious disease, oncology, gastroenterology, neurology, cardiology, and dermatology will be required to handle the complications of long-term HIV infection, ART medication side effects and the complications of immunosuppression when the patient transitions to AIDS.

Formation of an interprofessional teams is necessary to ensure patients are educated about their disease and treatment and have been shown to have improved adherence and outcomes for patients living with HIV.[7]

Antiretroviral Therapy (ART) is the current best medical management for individuals with HIV/AIDS. These drugs do not completely eradicate the virus and lifelong treatment is required until a method for permanent eradication is developed.

In a study done by The Strategies for Management of Anti-retroviral Therapy (SMART) study group, it was concluded that episodic (meaning when the CD4+ count dropped to 250 or below) therapy significantly increased the risk of opportunistic disease or death, as compared with continuous (ART when CD4+ count is 350 or more). [11]

Non-pharmacological intervention include:

- Physical Therapy

- Nutritional counselling

- Exercise

- Mental health support

- Alternative and complimentary interventions

Physical Therapy Management[edit | edit source]

Physical Therapists play an important role in treating conditions that limit the patient’s movement and function.

- Goals will be set to improve the quality of life and keep the patient active in both his/her life and in the community.

- Patients with HIV develop many of the functional limitations that any other patient may have, such as sports-related injuries or arthritis. In addition to managing impairments, these patients may have problems with the disease process, infections, and/or side effects of the medication.

- A physical therapist will develop a plan of care to help the patient improve his/her ability to do daily activities, improve heart health, improve balance, reduce pain, and maintain healthy body weight.

- In addition, this plan of care, a proper home exercise program will be prescribed to achieve goals set by the patient or physical therapist. A qualitative study by deBoer et al.[12] suggests that collaborating physiotherapists on the interprofessional health care team would help in addressing the unique requirements of patients living with HIV.

In addition to improving the above mentioned positive benefits, the therapist must also address the following issues:

- Quality of life issues

- Work environment

- Community management skills (how to access transportation, socialisation opportunities, shopping, banking, ability to access and negotiate health care and insurance systems)

- Integumentary care

What Does the Literature Say[edit | edit source]

The current literature states aerobic exercise, progressive resistance exercise, or a combination may attribute to the following benefits:

- Performing constant or interval training for at least 20 minutes at least 3 times per week for at least 5 weeks appears to be safe and may lead to significant improvements in cardiopulmonary fitness (maximum oxygen consumption) body composition (leg muscle area, percent body fat) and psychological status. [13]

- Progressive resistance exercise appears to be safe and may be beneficial for medically-stable adults living with HIV. [13]

- PRE or a combination of PRE and aerobic exercise may lead to statistically significant increases in weight and arm and thigh girth. [14]

- Trends toward improvement in sub-maximum heart rate and exercise time were found. [14]

- HIV patients have abnormally low functional capacities, expressed as lowered capacity to utilize and perform physical work. [15]

- Low to moderate intensity exercise does not alter CD4 cell counts or viral load, nor does it increase the prevalence of opportunistic infections.[15]

- Higher intensity aerobic exercise training has been effective at improving Functional Aerobic Capacity. [15]

- All in all, fatigue remains the most frequent and debilitating complaint of HIV-infected people.[16] With this said, patients who partake in aerobic exercise, PRE, or a combination will begin to achieve the above mentioned benefits to combat fatigue.

- A systematic review studying the effectiveness and efficacy of exercise for various diseases with neuropathic pain recommends aerobic and progressive resistance training as an adjunct treatment for treating neuropathic pain in people with HIV/AIDS.[17]

In addition to progressive resistance exercise and aerobic exercise, physical therapist may also perform the following interventions to treat any impairment the patient may present with:

- Stretching

- Soft Tissue and Joint Mobilization

- Gait and Balance Training

- Functional Electrical Stimulation/Neuromuscular Electrical Stimulation

- Proprioceptive Neuromuscular Facilitation

- Desensitisation Techniques

The Benefits of Exercise[edit | edit source]

Exercise can provide the following benefits for patients suffering from HIV/AIDS:

- Pain relief

- Reduction of muscle atrophy

- Regularity of bowels

- Enhances immune function (by increasing T helper/ inducer CD4 cells and activating CD8 cells)

- Improves cardiovascular function

- Improves pulmonary function

- Improves endurance

- Helps prevent pneumonia and other respiratory infections

- Reduces anxiety and improves mood

Standard AIDS/HIV Precautions for Therapists and Other Health Care Workers: [8][edit | edit source]

- Use protective barriers (gloves, glasses, gowns) when handling blood, body fluids, and infectious fluids.

- Wash hands and mucous membranes

- Prevent needle/scalpel sticks

- Use ventilation devices for resuscitation

- Don't treat a patient with HIV/AIDS if you have open wounds or skin lesions until lesions have healed.

- If pregnant take extra precautions

Outcome Measure for Quality of Life[edit | edit source]

Functional Assessment of HIV Infection (FAHI)

Differential Diagnosis[edit | edit source]

Many individuals with HIV/AIDS may remain asymptomatic for years, with a mean time of 10 years between exposure and development. Virtually, all the findings in the initial onset of AIDS may be found/mimic other diseases such as:

- Fever

- Headaches

- Night sweats

- Fatigue

- HTN

- Back pain

- Pulmonary complications ex. cough and SOA

- GI complaints (change in bowel habits and function)

- Cutaneous complaints (dry skin, new rashes, nail bed changes)

- Poor wound healing

- Thrush

- Easy Bruising

- Weight loss

- Herpes Simplex virus

- Cytomegalovirus

- Lymphoma

All of these signs/symptoms may be associated with other diseases, a combination of complaints is more suggestive of HIV infection than any one symptom alone. [18][19][20]

References[edit | edit source]

- ↑ Powell, M.K., Benková, K., Selinger, P., Dogoši, M., Kinkorová Luňáčková, I., Koutníková, H., Laštíková, J., Roubíčková, A., Špůrková, Z., Laclová, L. and Eis, V., 2016. Opportunistic infections in HIV-infected patients differ strongly in frequencies and spectra between patients with low CD4+ cell counts examined postmortem and compensated patients examined antemortem irrespective of the HAART era. PLoS One, 11(9), p.e0162704

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 2.4 2.5 Justiz AV, Gulick PG. HIV Disease.Available from:https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK534860/ (last accessed 26.2.2020)

- ↑ Gottlieb MS, Schanker HM, Fan PT, Saxon A, Weisman JD, Pozalski I. Pneumocystis pneumonia—Los Angeles. Mmwr. 1981 Jun 5;30(21):250-.

- ↑ Faria NR, Rambaut A, Suchard MA, Baele G, Bedford T, Ward MJ, Tatem AJ, Sousa JD, Arinaminpathy N, Pépin J, Posada D. The early spread and epidemic ignition of HIV-1 in human populations. science. 2014 Oct 3;346(6205):56-61

- ↑ The Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS (UNAIDS). Global HIV & AIDS Statistics—Fact Sheet. Available from: http://unaids.org/en/resources/fact-sheet. [Accessed 30 November 2021]

- ↑ WHO HIV/AIDS 15 November 2019 Available from:https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/hiv-aids (last accessed 26.2.2020)

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 Waymack JR, Sundareshan V. Acquired immune deficiency syndrome (AIDS). InStatPearls [Internet] 2019 Jan 22. StatPearls Publishing. Available from:https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK537293/ (last accessed 26.2.2020)

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 HIV/AIDS. Center for Disease Control and Prevention. http://www.cdc.gov/hiv/default.html. Updated November 22, 2019. Accessed 23 November 2019.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. HIV/AIDS Basics. AIDS.gov. http://aids.gov/hiv-aids-basics/. Accessed March 25, 2014.

- ↑ Treatment for HIV & AIDS. AIDS MEDS: Your Ultimate Guide to HIV Care. http://www.aidsmeds.com/list.shtml. Updated November 18, 2013. Accessed March 25, 2014.

- ↑ El-Sadr, WM; Lundgren, JD; Neaton, JD; Gordin, F; Abrams, D; Arduino, RC; Babiker, A; Burman, W; Clumeck, N; Cohen, CJ; Cohn, D; Cooper, D; Darbyshire, J; Emery, S; Fatkenheuer, G; Gazzard, B; Grund, B; Hoy, J; Klingman, K; Losso, M; Mejia, JMR; Markowitz, N; Neuhaus, J; Phillips, A; Rappoport, C; Strategies Management Antiretrovir,; CD4+count-guided interruption of antiretroviral treatment. NEW ENGL J MED, 2006; 355 (22): 2283 - 2296. http://eprints.ucl.ac.uk/6514/. Accessed March 25, 2014.

- ↑ deBoer H, Cudd S, Andrews M, Leung E, Petrie A, Carusone SC, O’Brien KK. Recommendations for integrating physiotherapy into an interprofessional outpatient care setting for people living with HIV: a qualitative study. BMJ open. 2019 May 1;9(5):e026827.

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 O'Brien K, Nixon S, Tynan AM, Glazier R. Aerobic exercise interventions for adults living with HIV/AIDS. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2010;(8):CD001796. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/20687068. Accessed March 25, 2014.

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 O'Brien K, Tynan AM, Nixon S, Glazier RH. Effects of progressive resistive exercise in adults living with HIV/AIDS: systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized trials. AIDS Care. 2008; 20:631-653. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/18576165. Accessed March 25, 2014.

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 15.2 Hand G, Phillips K, Dudgeon W, Lyerly G, Durstine J, Burgess S. Moderate intensity exercise training reverses functional aerobic impairment in HIV-infected individuals. AIDS Care. 2008; 20 (9): 1066-1074. http://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/09540120701796900#.UzGcZNnO_To. Accessed March 25, 2014.

- ↑ Barroso J, Voss J. Fatigue in HIV and AIDS: An Analysis of Evidence. Journal of the Assosciation of Nurses in AIDS Care. January/February 2013; 24: S5-S14. http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1055329012002427. Accessed March 25, 2014.

- ↑ Zhang YH, Hu HY, Xiong YC, Peng C, Hu L, Kong YZ, Wang YL, Guo JB, Bi S, Li TS, Ao LJ. Exercise for Neuropathic Pain: A Systematic Review and Expert Consensus. Frontiers in Medicine. 2021;8.

- ↑ Goodman C, Snyder T. Screening for Immunologic Disease. Differential Diagnosis for Physical Therapists Screening for Referral. 5th Edition. St. Louis, MO: Elsevier Saunders; 2013: 454-457.

- ↑ Goodman C, Fuller K. The Immune System. Pathology Implications for the Physical Therapist. 3rd Edition. St. Louis, MO: Elsevier Saunders; 2009: 257-274.

- ↑ Bennett N, Bronze M. HIV Disease Differential Diagnoses. Medscape. http://emedicine.medscape.com/article/211316-differential. Updated March 20, 2014. Accessed March 25, 2014.