Pressure Ulcers

Original Editor - Jayati Mehta

Top Contributors - Jayati Mehta, Naomi O'Reilly, Kim Jackson, Lucinda hampton, Adam Vallely Farrell, Tony Lowe, Rucha Gadgil, Jess Bell, Robin Tacchetti, Tarina van der Stockt, WikiSysop, Vidya Acharya, Lauren Lopez and Samuel Winter

Introduction[edit | edit source]

Decubitus ulcers, also termed bedsores or pressure ulcers, are skin and soft tissue injuries that form as a result of constant or prolonged pressure exerted on the skin.

These ulcers

- Occur at bony areas of the body such as the ischium, greater trochanter, sacrum, heel, malleolus (lateral more than medial), and occiput.

- Mostly occur in people with conditions that decrease their mobility making postural change difficult[1].

** Wheelchair users are at risk for pressure ulcers in the greater trochanters, ischial tuberosities and sacrum/coccyx.[2]

The terms decubitus ulcer (from Latin decumbere, “to lie down”), pressure sore, pressure ulcer and bedsores are often used interchangeably

Etiology[edit | edit source]

The development of decubitus ulcers is complex and multifactorial.

- Loss of sensory perception, locally and general impaired loss of consciousness, along with decreased mobility, are the most important causes that aid in the formation of these ulcers (patients are not aware of discomfort hence do not relieve the pressure).

Both external and internal factors work simultaneously, forming these ulcers.

- External factors; pressure, friction, shear force, and moisture

- Internal factors; fever, malnutrition, Anaemia, and endothelial dysfunction speed up the process of these lesions.

The dysfunction of nervous regulatory mechanisms responsible for the regulation of local blood flow is somewhat culpable in the formation of these ulcers

- Prolonged pressure on tissues can cause capillary bed occlusion and, thus, low oxygen levels in the area

- Over time, the ischemic tissue begins to accumulate toxic metabolites.

- Subsequently, tissue ulceration and necrosis occur.

Risk Factors Include:

- Neurologic Disease

- Cardiovascular Disease

- Prolonged Anesthesia

- Dehydration

- Malnutrition

- Hypotension

- Surgical Patients[1]

Epidemiology[edit | edit source]

Decubitus ulcers are a worldwide health care concern affecting tens of thousands of patients and costing over a billion dollars a year.[3] The cost of preventing and managing pressure ulcers have increased significantly since 2008[4] with more than 3 million adults being affected annually in the United States alone.[5]

- Their management costs billions of dollars per annum, burdening the already scarce health economy.

- Elderly patients are more prone to sacral decubitus ulcers

- Two-thirds of ulcers occur in patients who are over 70 years old

- Patients who are incontinent, paralyzed, or debilitated are more prone to getting them

- Individuals with spinal cord injury who use wheelchairs have a high risk of developing pressure ulcers[6]

- Patients with normal sensory status, mobility, and mental status are less likely to form these ulcers because their normal physiologic feedback system leads to frequent physical positional shifts. .

- Data that shows 83% of hospitalized patients with ulcers developed them within five days of their hospitalization[1]

Pathophysiology[edit | edit source]

Many factors contribute to the development of pressure ulcers, but pressure leading to ischemia and necrosis is the final common pathway.

- Result from constant pressure sufficient to impair local blood flow to soft tissue for an extended period.

- External pressure must be greater than the arterial capillary pressure (32 mm Hg) to impair inflow for an extended time

- Greater than the venous capillary closing pressure (8-12 mm Hg) to impede the return of flow for an extended time. [7]

- Tissues are capable of withstanding enormous pressures for brief periods, but prolonged exposure to pressures just slightly above capillary filling pressure initiates a downward spiral toward tissue necrosis and ulceration.

- The superficial dermis can tolerate ischemia for 2 to 8 hours before breakdown occurs.

- Deeper muscle, connective tissue, and fat tissues tolerate pressures for 2 hours or less (probably because of its increased need for oxygen and higher metabolic requirements).

- Often there is significant damage to underlying tissues while the epidermis and dermis remain intact.

- By the time ulceration is present through the skin level, significant damage of underlying muscle may already have occurred, making the overall shape of the ulcer an inverted cone.[8].

- Friction caused by skin rubbing against surfaces like clothing or bedding can also lead to the development of ulcers by contributing to breaks in the superficial layers of the skin.

- Moisture can cause ulcers and worsens existing ulcers via tissue breakdown and maceration[1]

Complications[edit | edit source]

Complications of pressure ulcers, some may be life-threatening, include:

- Cellulitis - Cellulitis is an infection of the skin and connected soft tissues. It can cause warmth, redness and swelling of the affected area. People with nerve damage often do not feel pain in the area affected by cellulitis.

- Bone and Joint Infections - An infection from a pressure sore can burrow into joints and bones. Joint infections (septic arthritis) can damage cartilage and tissue. Bone infections (osteomyelitis) can reduce the function of joints and limbs.

- Cancer - Long-term, non-healing wounds (Marjolin's ulcers) can develop into a type of squamous cell carcinoma.

- Sepsis - Rarely will a skin ulcer lead to sepsis.[9]

Pressure Sore Grading[edit | edit source]

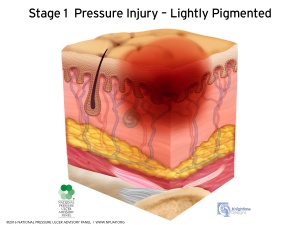

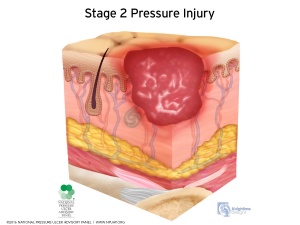

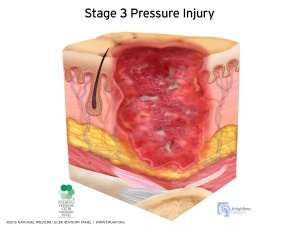

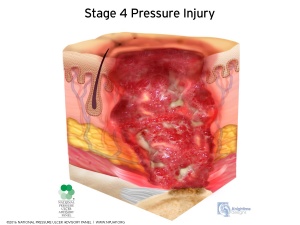

There are various stages of pressure injury, all of which classify the injury based on the depth of skin injury. Pressure ulcers are categorized into four stages:

- Stage 1: just erythema of the skin

- Stage 2: erythema with the loss of partial thickness of the skin including epidermis and part of the superficial dermis

- Stage 3: full thickness ulcer that might involve the subcutaneous fat

- Stage 4: full thickness ulcer with the involvement of the muscle or bone

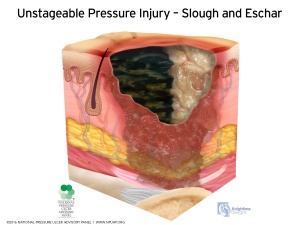

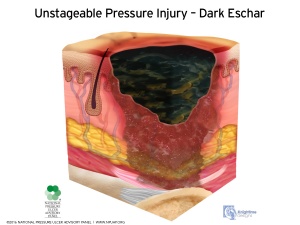

- Unstageable Pressure Injury: Obscured Full-thickness Skin and Tissue Loss - Full-thickness skin and tissue loss in which the extent of tissue damage within the ulcer cannot be confirmed because it is obscured by slough or eschar.

Symptoms[edit | edit source]

As mentioned previously, pressure ulcers can affect any part of the body that is put under pressure. They often develop gradually, but can sometimes form in just a few hours.

Early Symptoms

- Discolouration of parts of the skin- those with pale skin tend to develop red patches, while people with darker skin tend to get purple or blue patches

- Discoloured patches not turning white when pressure is applied

- A patch of skin that is warm, spongy or hard

- Pain or itchiness in the area affected

Later Symptoms

The skin may not be broken at first, but if the pressure ulcer gets worse it may form:

- An open wound or blister (Stage 2)

- A deep wound which reaches the deeper layers of the skin (Stage 3)

- A very deep wound that may reach the muscle and bone (Stage 4)

Clinical Presentation[edit | edit source]

The severity of pressure ulceration can be estimated by observing clinical signs. A progression from least tissue damage to most severe damage is presented here.[10]

- The first clinical sign of pressure ulceration is blanchable erythema along with increased skin temperature. If pressure is relieved, tissues may recover in 24 hours. If pressure is unrelieved, non-blanchable erythema occurs.

- Progression to a superficial abrasion, blister, or shallow crater indicates involvement of the dermis.

- When full-thickness skin loss is apparent, the ulcer appears as a deep crater. Bleeding is minimal, and tissues are indurated and warm. Eschar formation marks full-thickness skin loss. Tunnelling or undermining is often present.

- The majority of all pressure ulcers develop over six primary bony areas sacrum, coccyx, greater trochanter, ischial tuberosity, calcaneus (heel), and lateral malleolus.

Diagnosis[edit | edit source]

- If an individual has a history of a period of immobility followed by the discovery of a warm, red, spot over a bony prominence, a pressure ulcer can usually be confirmed.

- If the spot is unnaturally soft to the touch, sometimes referred to as “boggy,” this is enough evidence to suspect that damage is deeper than the epidermis.[10]

The following tests may be performed :

- Blood Tests

- Tissue cultures to diagnose a bacterial or fungal infection in a wound that doesn't heal with treatment or is already at stage IV.

- Tissue cultures to check for cancerous tissue in a chronic, non-healing wound.[11]

Treatment / Management[edit | edit source]

Managing decubitus ulcers is complicated as there is no fixed treatment regime/algorithm.

Once a pressure sore has developed, there should be no delay in treatment, and management should start immediately.

- Treatment varies between site, stage, and associated complications of the ulcer.

- The goal of all the various treatment options is to;

- minimize the pressure exerted on the ulcer,

- minimize contact of the ulcer with a hard surface, decrease moisture, and to keep it as aseptic or least septic as possible.

- The choice of treatment options should be according to the stage/grade of the ulcer, and what the purpose of the treatment should be (decreasing moisture, removal of necrotic tissue, controlling bacteremia).

- Prevention is clearly the best treatment with excellent skincare, pressure dispersion cushions, support surfaces and seat comfort.

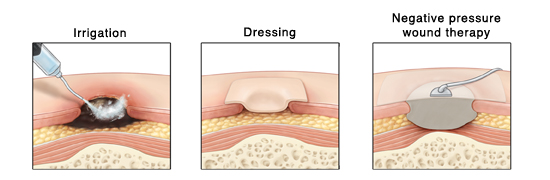

Support surfaces decrease the amount of pressure on the wound. Support surfaces can be either static (e.g., air, foam, and water mattress overlays) or dynamic (e.g., alternating air overlay). Repositioning and turning the patient every two hours can also lessen pressure on the area, but some patients may require more frequent repositioning, while others may require less frequent repositioning.

- In some cases, urinary and faecal diversion may be necessary depending on the site of ulcer, being prone to urine or faecal contamination.

- Hydrocolloid dressings should be used.

- Good antibiotic cover decreases the risk of sepsis.

- The depth and severity of the ulcer determine whether surgical management may be required.

- Some evidence exists suggesting that hyperbaric oxygen therapy can help with wound healing, as it improves oxygenation in and around the area of the wound.

In Summary, treatment of pressure ulcers has its basis in the following:

- Prevention of Additional Ulcers

- Decreasing Pressure on Wound

- Wound Management

- Surgical Intervention

- Nutrition [1]

Prevention[edit | edit source]

Patients and their family members should have a clear idea that preventing recurrence requires commitment and responsibility. They should

- Receive education on how to manage the condition in the hospital and as well as in their homes.

- Be familiar with warning signs like skin discoloration, ulceration, discharge, or a foul smell from the ulcer site and body areas with decreased or no sensation.

The patient should

- Move or turn every 2 hours; it could not be done by themselves, or they should ask someone to help them.

- Use air or water mattress in their homes.

- Have adequate food intake adequate and it should consist of a balanced and healthy diet[1].

Improving Patient Outcomes[edit | edit source]

The main goal is to prevent a decubitus ulcer by decreasing the pressure acting on the affected site.

This goal requires an interprofessional team, including primary care providers, wound care specialists, surgeons, specialty-trained wound nurses, physical therapists, and nurses aides.

- Physiotherapists should try to increase their physical activity, at appropriate level.

- Nurses provide care, monitor patients, and notify the team of issues. Nurses aides are often responsible for turning and repositioning patients.

- Air-fluidized or foam mattresses should be used, frequent postural changes, provision of adequate nutrition, and treatment of any underlying systemic illnesses.

- Debridement should take place to remove dead tissue that serves as the optimum medium for the growth of bacteria.

- Hydrogels or hydrocolloid dressing should be used, which aid in wound healing.

- Tissue cultures are necessary, so the most directed antibiotic can be administered, which can involve the pharmacist and the latest antibiogram data.

- The patient should be kept pain free by giving analgesics.

- Frequent follow-ups are an absolute necessity and a team approach to patient education and management involving the wound care nurse and wound care clinician will lead to the best results.[1]

Reference[edit | edit source]

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 1.5 1.6 Zaidi SR, Sharma S. Decubitus Ulcer. InStatPearls [Internet] 2020 Jan 18. StatPearls Publishing. Available from:https://www.statpearls.com/kb/viewarticle/20286 (last accessed 21.9.2020)

- ↑ Sprigle S, Sonenblum SE, Feng C. Pressure redistributing in-seat movement activities by persons with spinal cord injury over multiple epochs. PloS one. 2019 Feb 13;14(2):e0210978.

- ↑ Bansal C, Scott R, Stewart D, Cockerell CJ. Decubitus ulcers: a review of the literature. Int J Dermatol. 2005;44(10):805-810. doi:10.1111/j.1365-4632.2005.02636.x Available from: (last accessed 21.9.2020)https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/16207179/

- ↑ Stephens M, Bartley CA. Understanding the association between pressure ulcers and sitting in adults what does it mean for me and my carers? Seating guidelines for people, carers and health & social care professionals. J Tissue Viability. 2018;27(1):59-73.

- ↑ Mervis JS, Phillips TJ. Pressure ulcers: Pathophysiology, epidemiology, risk factors, and presentation. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;81(4):881-90.

- ↑ Hubli M, Zemp R, Albisser U, Camenzind F, Leonova O, Curt A et al. Feedback improves compliance of pressure relief activities in wheelchair users with spinal cord injury. Spinal Cord. 2021;59:175–84.

- ↑ Bridel J.

The aetiology of pressure sores. Journal of Wound Care. 1993 Jul 2;2(4):230-8. - ↑ Defloor T. The risk of pressure sores: a conceptual scheme. Journal of clinical nursing. 1999 Mar;8(2):206-16.

- ↑ Ahn H, Cowan L, Garvan C, Lyon D, Stechmiller J. Risk factors for pressure ulcers including suspected deep tissue injury in nursing home facility residents: analysis of national minimum data set 3.0. Advances in skin & wound care. 2016 Apr 1;29(4):178-90.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 Susan B. O’Sullivan,Thomas J. Schmitz,George D. Fulk, Physical Rehabilitstion,6th edition,United States of America,F.A. Davis Company,2014

- ↑ http://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/bedsores/basics/tests-diagnosis/con-20030848