Neuropathic Pain

Original Editor - Kerstin McPherson

Top Contributors - Andeela Hafeez, Melissa Coetsee, Kerstin McPherson, Vanessa Rhule, Riccardo Ugrin, Lucinda hampton, Kim Jackson, Admin, Evan Thomas, Chrysolite Jyothi Kommu, Kapil Narale, Temitope Olowoyeye, Jo Etherton, WikiSysop, Vidya Acharya, Lauren Lopez, 127.0.0.1, Wendy Walker, Carina Therese Magtibay, Oyemi Sillo and Amanda Ager

Definition[edit | edit source]

The International Association for the Study of Pain (2011) defines neuropathic pain as ‘pain caused by a lesion or disease of the somatosensory nervous system’.

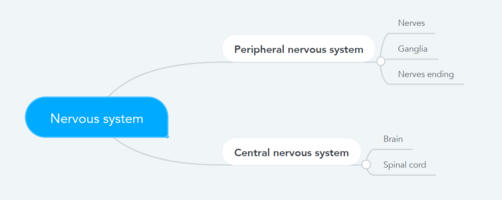

It can result from damage anywhere along the neuraxis: peripheral nervous system, spinal or supraspinal nervous system[1].

- Central neuropathic pain is defined as ‘pain caused by a lesion or disease of the central somatosensory nervous system’.

- Peripheral neuropathic pain is defined as ‘pain caused by a lesion or disease of the peripheral somatosensory nervous system’.

Neuropathic pain is very challenging to manage because of the heterogeneity of its aetiologies, symptoms and underlying mechanisms[2].

Causes[edit | edit source]

Conditions frequently associated with neuropathic pain can be categorized into two major group, pain due to damage in the central nervous system and pain due to damage to the peripheral nervous system.

Central nervous system causes include:

- Cortical and sub-cortical strokes, traumatic spinal cord injuries, syringomyelia and syringobulbia, trigeminal and glossopharyngeal neuralgias, neoplastic and other space-occupying lesions.

Peripheral nervous system causes include:

- Nerve compression/ entrapment neuropathies (eg carpal tunnel syndrome, thoracic outlet syndrome or piriformis syndrome [3]) , ischemic neuropathy, nerve root compression

- post traumatic neuropathy (occurs after injury or medical procedures, such as surgery or injection)[3],

- post-amputation stump and phantom limb pain (the exact cause of phantom limb pain is unknown, it appears to result when the nerves and the brain send faulty signals to the limb as the circuitry attempts to "rewire" itself[3]),

- postherpetic neuralgia (can occur following a viral infection of herpes zoster (aka shingles")[3]

- Complex Regional Pain Syndrome (CRPS)

- diabetic neuropathy

- Cancer-related neuropathies.[4]

Abnormal Impulse Generating Sites (AIGS)[edit | edit source]

- Following a peripheral origin, central sensitization may be sustained as a result of ectopic neuronal activity both in peripheral nerves and, as a consequence, in dorsal root ganglion and in the dorsal horn of the spinal cord.

- Abnormal Impulse Generating Sites (AIGS) are defined as the unmyelinated sites along the damaged axon in which the number, kind and excitability of ion channels are altered. This change in ion channel distribution make the site scusceptible to nonnoxious stimuli as mechanical, chemical, or thermal stimuli[5][6].

- Ectopic impulses may also been generated spontaneously. Infact the high density of ion channels may result in a close resting potential to the threshold.[7]

- Despite of that when an injury occurs to the nerves, neurons in the dorsal root ganglion increase their nociceptive signaling through increases in neuronal excitability and the creation of ectopic discharges. This is consequent of profound changes in the distribution of the receptors on dorsal root ganglion cell bodies.

- Following limb amputation for examples, the axons are disconnected from their distal targets and inflammation and sprouting occur in the resulting residual limb, where a neuroma can form. A neuroma may indeed represent an anatomically site for generating nociceptive impulses.

- However neuromas, AIGS and dorsal root ganglion change in receptors can together be the cause of peripheral nervous system cause for the phantom limb pain.[8]

- AIGS fires antidromically and orthodromically, resulting in constant noxious stimulus into the Central nervous system and neurogenic inflammation in the tissues. For this reason AIGS can persist even though the primary injury on the axon is complete healed.

Pathophysiology[edit | edit source]

Neuropathic pain is the result of disease or injury to the peripheral or central nervous system and the lesion may occur at any point.

- These damaged nerve fibers send incorrect signals to other pain centers.

- The impact of a nerve fiber injury includes a change in nerve function—both at the site of the injury and areas around the injury[1].

- Neuropathic symptoms can infact originate peripherally via ectopic impulses along the Aβ, Aδ, and C fibers, arising as spontaneous activity due to processes such as damaged ion channels that accumulate along affected sensory axons, causing a drift toward threshold potential[9].

- As the damaged nerve begins firing ectopically, A-fiber sprouting into the pain layers (laminae I and II of the dorsal horn) may occur. Because of this sprouting process, when nerves that do not normally transmit pain sprout into these more superficial laminas, pain may result from nonnoxious stimuli[10].

- As it sayed before, following a peripheral origin, central sensitization may develop as a result of ectopic neuronal activity in the spinal cord dorsal horn, implying a potential autonomous pain-generating mechanism.[4] Thus may contribute to an increase in the size of the sensory receptive field, to a reduced threshold for pain perception, and hypersensitivity to various innocuous stimuli in the dorsal horn.

- The antidromic direction of the impulse generated in the AIGS can maintain the inflammation of the tissues. This may substain the chronic chemical stimuli of the peripheral nociceptive pain.

The mechanism underlying neuropathic pain is still not clear. Several animal studies have shown that many mechanisms may be involved.

- First order neurons may increase their firing if they are partially damaged and increase the number of sodium channels.

- Ectopic discharges are a result of enhanced depolarization at certain sites in the fiber, leading to spontaneous pain and movement-related pain.

- Inhibitory circuits may be impaired at the level of the dorsal horn or brain stem (or both) allowing pain impulses to travel unopposed. See Pain Facilitation and Inhibition

- In addition, there may be alterations in the central processing of pain when (due to chronic pain and use of some drugs), second- and third-order neurons may develop a “memory” of pain and become sensitized. There is then heightened sensitivity of spinal neurons and reduced activation thresholds. [2]

See also Mechanisms of peripheral neuropathic pain: implications for musculoskeletal physiotherapy

Clinical Features[edit | edit source]

Traits that differentiate neuropathic pain from other types of pain include pain and sensory symptoms lasting beyond the healing period. It is characterized in humans by spontaneous pain, allodynia (the experience of non-noxious stimuli as painful), and causalgia (constant burning pain).

- Neuropathic pain consists of both “negative” symptoms (sensory loss and numbness) and “positive” symptoms (paresthesias, spontaneous pain, increased sensation of pain)[1].

- Spontaneous pain includes sensations of ‘pins and needles,’ shooting, burning, stabbing and paroxysmal pain (electric-shock like) often associated with dysesthesias and paresthesias. These sensations not only affect the patient’s sensory system, but also the patient’s well-being, mood, focus and thinking.

- The onset of pain may be delayed, the commonest examples are central poststroke pain (thalamic), or the phantom limb pain. Infact both neuropathic pain may start months or years after the primary event of injury.

- Pain is often of mixed nociceptive and neuropathic types, eg mechanical spinal pain with radiculopathy or myelopathy.

Assessment[edit | edit source]

One of the challenges, in regards to neuropathic pain, is the ability to assess it. There is a dual component to this: assessing quality, intensity and improvement; and accurately diagnosing neuropathic pain.

There are, however, some diagnostic tools that may assist clinicians in evaluating neuropathic pain. eg nerve conduction studies and sensory-evoked potentials can identify and quantify the extent of damage to sensory, but not nociceptive, pathways by monitoring neurophysiological responses to electrical stimuli.

Mechanical sensitivity to tactile stimuli is measured with von Frey hairs, pinprick with weighted needles, vibration sensitivity with vibrameters and thermal pain with thermodes.

It is also very important to perform a thorough neurological evaluation to identify motor, sensory and autonomic dysfunctions. Finally, there are numerous questionnaires used to distinguish neuropathic pain from nociceptive pain[1].e.g., the Neuropathic Questionnaire11 and ID Pain.

Management[edit | edit source]

Neuropathic pain often responds poorly to standard pain treatments and occasionally may get worse instead of better over time. For some people, it can lead to serious disability. A multidisciplinary approach that combines therapies, however, can be a very effective way to provide relief from neuropathic pain.The multidisciplinary approach including:

- Physical therapy;

- Low impact general physical activities;

- Counselling;

- Relaxation therapy;

- Massage therapy;

- Acupuncture;

- Pharmacological treatment and drugs mdications;

- A number of pharmacological treatments can be used to manage neuropathic pain outside of specialist pain management services. However, there is considerable variation in how treatment is initiated, the dosages used and the order in which drugs are introduced, whether therapeutic doses are achieved and whether there is correct sequencing of therapeutic classes. A further issue is that a number of commonly used treatments are unlicensed for treating neuropathic pain, which may limit their use. These factors may lead to inadequate pain control, with considerable morbidity.

- Exercise training can be an effective intervention for many of those symptoms associated with peripheral neuropathy[11][12].

- Effective management of the condition can also help prevent further nerve damage.

For commonly used pharmacological treatments see Neuropathic Pain Medication [2].

Physical Therapy Management[edit | edit source]

Physical therapy modalities and rehabilitation techniques are important options and must be considered when pharmacotherapy alone is not sufficient [13].Physical therapy tackles the physical side of the inflammation, stiffness, and soreness with exercise, manipulation, and massage, but it also works to help the body heal itself by encouraging the production of the body's natural pain-relieving chemicals. This two-pronged approach is what helps make physical therapy so effective as a pain treatment.[14]

In addiction to that, exercise is useful to reorganise and sprouting the cortical body representation: the profound change in the neuromatrix related to chronic pain it is part of the central sensitisation [15][16].

- TENS therapy has low quality of evidence for been effective in the treatment of painful peripheral neuropathy. Low level laser therapy could otherwise has positive effects on the control of analgesia for neuropathic pain [17][18].

- Neurostimulation techniques including transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS) and cortical electrical stimulation (CES), spinal cord stimulation (SCS) and deep brain stimulation (DBS) have also been found effective in the treatment of neuropathic pain.

- Exercise and movement representation techniques (that is, treatments such as mirror therapy and motor imagery that use the observation and/or imagination of normal pain-free movements) have been suggested to be beneficial in neuropathic pain management. Recently, mirror therapy has used for not only patients with phantom limb pain, but also for patients with complex regional pain syndrome and strokes[19]. However the quality of evidence supporting these interventions for neuropathic pain is weak and needs further investigation.

- Exercise: exercising for just 30 minutes a day on at least three or four days a week will help you with chronic pain management by increasing:[14]Muscle Strength; Endurance; Stability in the joints; Flexibility in the muscles and joints. Keeping a consistent exercise routine will also help control pain. Regular therapeutic exercise will help you maintain the ability to move and function physically, rather than becoming disabled by your chronic pain.

- There are studies showing that exercise may be an important part of the treatment and prevention of neuropathic pain after chemotherapy. Although more information is required and detailed exercise prescriptions do not yet exist for patients receiving cancer treatment.[20] It has been also found that physical exercise, such as forced treadmill running and swimming, can sufficiently improve mechanical allodynia and heat hyperalgesia in animal models of neuropathic pain. [21]

Please watch the following video for relevant about neuropathic pain.

Management of Neuropathic Pain[22]

== References ==

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 PPM The Pathophysiology of Neuropathic Pain Available:https://www.practicalpainmanagement.com/pain/neuropathic/pathophysiology-neuropathic-pain (accessed 30.10.2021)

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 NICE. Neuropathic pain in adults: pharmacological management in non-specialist settings.Available: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK552848/(accessed 30.9.2021)

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 Neuropathy-Nerve pain-Dr. Mary Car-Blanchard, OTD/OTR/L and the following editorial advisors: Steve Meadows, MD, Ernie F. Soto, DDS, Ronald J. Glatzer, MD, Jonathan Rosenberg, MD, Christopher M. Nolte, MD, David Ap

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 Haroutounian S, Nikolajsen L, Bendtsen TF, Finnerup NB, Kristensen AD, Hasselstrøm JB, Jensen TS . Primary afferent input critical for maintaining spontaneous pain in peripheral neuropathy. Pain, 2014; 155 (7): 1272-9

- ↑ Greening J, Lynn B. Minor peripheral nerve injuries an underestimated source of pain? Manual Therapy, 1998; 3: 187-194

- ↑ Gifford L. Acute low cervical nerve root conditions: symptom presentation and pathobiological reasoning. Manual Therapy, 2001; 6: 106-115

- ↑ Sapunar D, Kostic S, Banozic A, Puljak L. Dorsal root ganglion — a potential new therapeutic target for neuropathic pain. J Pain Res. 2012;5:31–38

- ↑ Collins KL, Russell HG, Schumacher PJ, et al. A review of current theories and treatments for phantom limb pain. J Clin Invest. 2018;128(6):2168-2176.

- ↑ Ochoa J, Torebjork HE. Paraesthesiae from ectopic impulse generation in human sensory nerves. Brain. 1980;103:835–854.

- ↑ Harden, R. Chronic Neuropathic Pain: mechanisms, diagnosis and treatment. The Neurologist, 2005.11(2): 111–122.

- ↑ Dobson JL, McMillan J, Li L. Benefits of exercise intervention in reducing neuropathic pain. Front Cell Neurosci. 2014;8:102

- ↑ Detloff MR, Smith EJ, Quiros Molina D, Ganzer PD, Houlé JD. Acute exercise prevents the development of neuropathic pain and the sprouting of non-peptidergic (GDNF- and artemin-responsive) c-fibers after spinal cord injury. Exp Neurol. 2014 May;255:38-48.

- ↑ Akyuz G, Kenis O. Physical therapy modalities and rehabilitation techniques in the management of neuropathic pain. Am J Phys Med Rehabil. 2014 Mar;93(3):253-9.

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 Physical Therapy for Pain Management.By Diana Rodriguez | Medically reviewed by Pat F. Bass III, MD, MPH

- ↑ Melzack R. Pain and the neuromatrix in the brain. J Dent Educ. 2001 Dec;65(12):1378-82.

- ↑ Trout KK. The neuromatrix theory of pain: implications for selected nonpharmacologic methods of pain relief for labor. J Midwifery Womens Health. 2004 Nov-Dec;49(6):482-8.

- ↑ Gibson W, Wand BM, O'Connell NE. Transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation (TENS) for neuropathic pain in adults. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2017 Sep 14;9(9):CD011976

- ↑ de Andrade AL, Bossini PS, Parizotto NA. Use of low level laser therapy to control neuropathic pain: A systematic review. J Photochem Photobiol B. 2016 Nov;164:36-42.

- ↑ Kim SY, Kim YY. Mirror therapy for phantom limb pain. Korean J Pain. 2012;25(4):272-274.

- ↑ Majithia N, Loprinzi CL, Smith TJ.New Practical Approaches to Chemotherapy-Induced Neuropathic Pain: Prevention, Assessment, and Treatment. Oncology (Williston Park). 2016 Nov 15;30(11)

- ↑ Kami K, Tajima F, Senba E. Exercise-induced hypoalgesia: potential mechanisms in animal models of neuropathic pain. Anat Sci Int. 2016 Aug 2. [Epub ahead of print]

- ↑ Management of Neuropathic Pain. Available from: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=hDu_WdRNDzo&t=796s