Pain Behaviours

Top Contributors - Joanne Garvey, Kapil Narale, Jo Etherton, Aminat Abolade, Evan Thomas, Tarina van der Stockt, Kim Jackson, Lucinda hampton, Melissa Coetsee, Rachael Lowe, Lauren Lopez, Carina Therese Magtibay and Aya Alhindi

Introduction[edit | edit source]

When we think of pain behaviours, we tend to think of our behaviour to pain but the type of pain and how they present is also an important factor in understanding pain. Human Pain Behaviours is much more than a sensory perception of tissue injury. Pain is a complex and unpleasant multi-dimensional experience of the self associated with perceived tissue threat[1].

Pain behaviours can be adaptive or pathogenic, as when the pain behaviour is excessive in comparison to the objective pathology. It has been found that when pain behaviour exists in pain patients, a psychiatric disease may aggravate pain. [2]

Pain types differ. There are 4 widely accepted pain types relevant for musculoskeletal pain[3]:

Other types of pain are also described here:

For more information also see:

Pain Behaviours[edit | edit source]

There are different types of behaviours that can be exhibited with the feeling of pain. These can include phantom limb pain or pain catastrophising. There are many different types of pain related behaviours that can be experienced via the different types of pain presentations, as listed above (nociceptive and neuropathic pain).

Different behaviours and characteristics can be exhibited between different types of groups. The points below outlines some of these different types of behaviours: [4]

Demographic factors[edit | edit source]

- Demographic factors do not influence pain. However, they can influence differing individual factors which would account for a varied person's perception of pain

Sex differences[edit | edit source]

- Chronic pain is more prevalent among Women than Men

- Women were more likely to report persistent and bothersome pain - they are at a greater risk for more chronic type pain, like migraines and tension-type headaches, low back pain, fibromyalgia and widespread pain, temporomandibular disorders, irritable bowel syndrome, and osteoarthritis

- Women display greater sensitivity than men, including pain threshold, pain tolerance, and ratings of suprathreshold stimuli, females have shown greater adaptation than men, which indicates a stronger pain inhibitory response to thee stimuli

- Possible mechanisms can present as effects of sex hormones, differences in endogenous opioid function, cognitive/affective influences, and contributions of social factors such as stereotypic gender roles

Ethnic differences[edit | edit source]

- Pain prevalence was lowest among Asians compared to other race/ethnic groups in the US - the highest prevalence of persistent pain among whites, in comparison to other ethnic groups

- Among older adults some studies reported a higher pain prevalence among minorities compared to whites, while others reported no differences in pain prevalence

- While conflicting evidence exists regarding pain prevalence among minority versus majority ethnic groups, studies consistently suggest that the severity and impact of pain is greater among minorities who are experiencing chronic pain

- Differences in pain perception between racial/ethnic groups may contribute to variances in severity of clinical pain - it is interesting to note that African Americans display greater experimental pain sensitivity compared to non-Hispanic whites

- Mechanisms include factors related to socioeconomic standing and access to adequate health care Increased pain prevalence and higher pain intensity in lower SES groups

- Minority patients are at greater risk for undertreatment of their pain, which could obviously contribute to the greater clinical pain severity observed among members of minority groups

- Pain coping also differs significantly across racial/ethnic groups

- Biological factors, such as genetic contributions, may play a role in racial/ethnic differences in pain responses

[edit | edit source]

- The prevalence of joint pain, lower extremity pain and neuropathic pains tend to increase monotonically with age.

- General chronic pain increases in prevalence until middle age, at which time the prevalence plateaus.

- Pain conditions such as headache, abdominal pain, back pain, and temporomandibular disorders show peak prevalence in the third to fifth decades of life, after which their frequency decreases.

- Older adults have reported lower acute pain intensity in some studies.

- Age-related differences in the intensity and impact of chronic pain have not been consistently demonstrated

- Older adults show less sensitivity to brief, cutaneous pains (e.g. heat pain threshold); however, sensitivity to more sustained pain stimuli that impact deeper tissues increases with age

- Several studies have demonstrated increased temporal summation of pain among older adults, while conditioned pain modulation consistently has been found to decrease with age

- Aging is associated with a shift in pain modulatory balance, such that older adults show enhanced pain facilitation combined with decreased pain inhibition

Nociceptive Pain[edit | edit source]

Nociceptive pain can be thought of as pain associated with tissue injury or damage or even potential damage.

- Nociceptors: are sensory endings on nerves that can be excited or sensitized and signal potential tissue damage.

- Examples of nociceptive pain include jamming your finger in a car door, spraining your ankle or touching the hot plate on the stove.

Nociceptive Inflammatory Pain[edit | edit source]

- Nociceptive inflammatory pain is associated with tissue damage and inflammatory response.

- Inflammation: is a coordinated body system response that is designed to help heal tissue damage.

- The inflammatory response is well-coordinated and involves blood-borne chemicals, immune system chemicals and some chemicals released from specialised nerve fibres. These chemicals communicate with each other to help coordinate tissue repair.

- Examples of nociceptive pain include: jamming fingers in a car door, a sprained ankle, non-specific low back pain or neck pain, fractures.

- There may be signs of tissue injury such as swelling, redness and later purple or yellowing of the skin, a limb that looks distorted, increased sensitivity to touch and movement. Such signs are part of tissue healing.

Neuropathic Pain[edit | edit source]

- Neuropathic pain is pain associated with injury or disease of nerve tissue.

- People often get this type of pain when they have shingles, sciatica, cervical or lumbar radiculopathy, trigeminal neuralgia, or diabetic neuropathy.

- Neuropathic pain is often described as burning, shooting, stabbing, prickling, electric shock-like pain, with hypersensitivity to touch, movement, hot and cold and pressure.

- Neuropathic pain may cause even a very light touch or gentle movement to be very painful.

Nociplastic Pain[edit | edit source]

Nociplastic pain is mechanistically different from nociceptive pain and neuropathic pain.

The following is the definition recommended by the IASP:

"Nociplastic Pain is a term used to describe persistent pain that arises from altered nociception, despite no clear evidence of actual or threatened tissue damage causing the activation of peripheral nociceptors, or evidence for disease or lesion of the somatosensory system causing the pain."

Some facts about nociplastic pain:

- It is an umbrella term. [5]

- It can be defined as chronic pain leading towards an altered nociceptive function.

- It results in increased sensitivity from the altered function of pain-related sensory pathways in the periphery and central nervous system (CNS). [6] [7]

- It consists of multifactorial processes from different inputs, which could be either a bottom-up response to a peripheral nociceptive, a neuropathic stimulus (known as central sensitisation), or a top-down CNS-driven response. [6]

- It is not a diagnosis but a descriptor of the pain experienced. [5][8]

- It encompasses pain from stereotypical terms such as dysfunctional pain or medically unexplained somatic syndromes. [6]

- Conditions that fall under the umbrella of Nociplastic Pain include fibromyalgia, complex regional pain syndrome, other musculoskeletal pain such as chronic low back pain, and visceral pain disorders such as irritable bowel syndrome and bladder pain syndrome. [5]

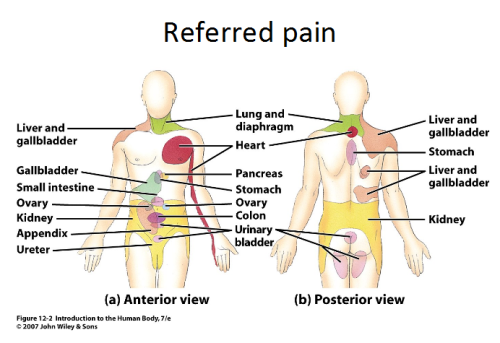

Referred Pain[edit | edit source]

- Referred pain is pain perceived at a location other than the site of the painful stimulus.

- It usually originates in one of the visceral organs but is felt in the skin or sometimes in another area deep inside the body.

- Its mechanism is likely due to the fact that pain signals from the viscera travel along the same neural pathways used by pain signals from the skin.

- The result is the perception of pain originating in the skin rather than in a deep-seated visceral organ or neural structure.

- Visceral nociceptors project into the spinal cord via small diameter myelinated and unmyelinated fibres from the autonomic nervous system. They go on to synapse close to the point of embryonic origin in the spine.

- When an organ develops pain, it can therefore be perceived as being at a different point in the body, on the surface, rather than in the organ itself.[9]

Mechanism[edit | edit source]

Hyperalgesia[edit | edit source]

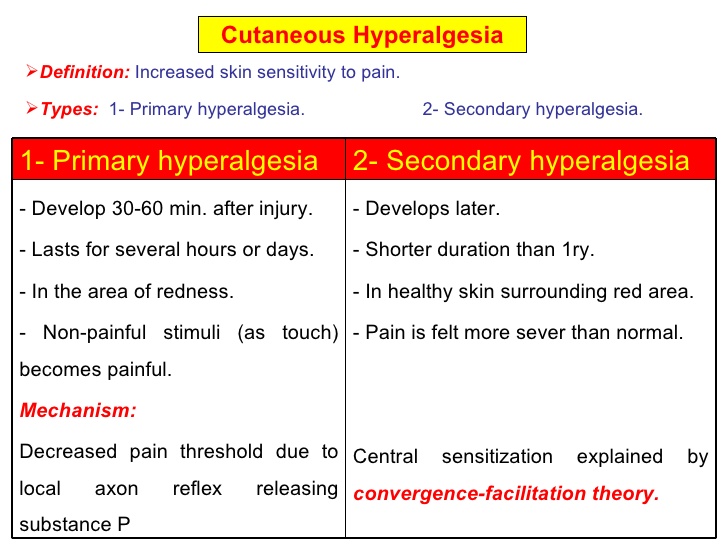

- Hyperalgesia is defined as "An increased sensitivity to pain, which may be caused by damage to nociceptors or peripheral nerves".[11]

- It is divided into two types; primary and secondary.

- Primary hyperalgesia - pain and sensitivity in the damaged tissues.

- Secondary hyperalgesia - pain and sensitivity that occurs in area around the damaged tissues.

- Substance P appears to have a significant role in the sensitization of nociceptors, which may explain the heightened feeling of pain in injured tissue (primary hyperalgesia). Although, this does not account for the perception of non-painful stimuli as painful.

- Secondary hyperalgesia is most likely accounted for by changes in the dorsal horn which affect the processing of sensory information. [9]

- Normally silent nociceptors are likely recruited, and sprouting of large diameter sensory afferent occurs projecting into the dorsal horn laminae.

Allodynia[edit | edit source]

- Central pain sensitization (increased response of neurons) following painful, often repetitive, stimulation.

- Allodynia can lead to the triggering of a pain response from stimuli which do not normally provoke pain.[12]

Types of allodynia: - Mechanical allodynia (also known as tactile allodynia)

- Static mechanical allodynia – pain in response to light touch/pressure[13]

- Dynamic mechanical allodynia – pain in response to stroking lightly[14]

- Thermal (hot or cold) allodynia – pain from normally mild skin temperatures in the affected area

- Movement allodynia - pain triggered by normal movement of joints or muscles.

Pain Behaviours[edit | edit source]

Inflammatory Pain[edit | edit source]

One of the cardinal features of inflammatory states is that normally innocuous stimuli produce pain.[15]

Please follow the link to this article for an overview of Inflammatory pain

Further Watching[edit | edit source]

Below is a 45 minutes video on Pain Mechanisms

References[edit | edit source]

- ↑ Visser EJ, Davies S. What is pain? II: Pain expression and behaviour, evolutionary concepts, models and philosophies. Australasian Anaesthesia. 2009(2009):35. Available from:https://www.notredame.edu.au/__data/assets/pdf_file/0013/3046/What-is-pain-part-II-philosophy-behaviours-ANZCA-Blue-Book.pdf (last accessed 20.5.2020)

- ↑ Güleç, G., & Güleç, S. (2006). Pain and pain behavior. Agri: Agri (Algoloji) Dernegi’nin Yayin organidir [Agri: The journal of the Turkish Society of Algology], 18(4), 5–9. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/17457708/

- ↑ Painhealth Pain Types https://painhealth.csse.uwa.edu.au/pain-module/pain-types/ (last accessed 20.5.2020)

- ↑ Fillingim R.B. Individual Differences in Pain: Understanding the Mosaic that Makes Pain Personal. Pain. 2017:158(1):1-18.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 International Association for the Study of Pain - What's in a Name for Chronic Pain? “Nociplastic pain” was officially adopted by IASP as the third mechanistic descriptor of chronic pain. Available from: https://www.iasp-pain.org/publications/pain-research-forum/prf-news/92059-whats-name-chronic-pain/ (accessed 11 August 2023).

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 Fitzcharles M-A, Cohen S.P, Clauw D.J, Littlejohn G, Usui C, Häuser W. Nociplastic pain: towards an understanding of prevalent pain conditions. The Lancet. 2021:397:2098–2110.

- ↑ Chimenti R.L, Frey-Law L.A, Sluka K.A. A Mechanism-Based Approach to Physical Therapist Management of Pain. Journal of the American Physical Therapy Association. 2018:98(5):302–314.

- ↑ Slater H, Hush J. Pain Terminology: Introduction Of a Third Clinical Descriptor. Pain Terminology. 2018:3:7-8.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 Roger, Barker, Barasi, Neal. Neuroscience at a glance.1999 Blackwell science.

- ↑ UChicago Online. Visceral Pain. Available from: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=w_uSsFeA_lc [last accessed 1/8/2021]

- ↑ Hart BL. Biological basis of the behavior of sick animals. Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews. 1988 Jun 1;12(2):123-37.

- ↑ Merskey & Bogduk (Eds.) Classification of Chronic Pain. Seattle: IASP Task Force on Taxonomy, 1994

- ↑ Attal N, Brasseur L, Chauvin M, Bouhassira D. Effects of single and repeated applications of a eutectic mixture of local anaesthetics (EMLA®) cream on spontaneous and evoked pain in post-herpetic neuralgia. Pain. 1999 May 1;81(1-2):203-9.

- ↑ LoPinto C, Young WB, Ashkenazi A. Comparison of dynamic (brush) and static (pressure) mechanical allodynia in migraine. Cephalalgia. 2006 Jul;26(7):852-6.

- ↑ Kidd BL, Urban LA. Mechanisms of inflammatory pain. British journal of anaesthesia. 2001 Jul 1;87(1):3-11.

- ↑ Tony Dickenson. Update on Pain Mechanisms. Available from: https://vimeo.com/88634321 [last accessed 1/8/2021]