Pain Mechanisms

Original Editor - Tiara Mardosas

Top Contributors - Tiara Mardosas, Carin Hunter, Jess Bell, George Prudden, Admin, Kim Jackson, Rachael Lowe, Scott Buxton, Carina Therese Magtibay, Naomi O'Reilly, Venus Pagare and Tarina van der Stockt

General Overview of Pain[edit | edit source]

The most widely accepted and current definition of pain, established by the International Association for the Study of Pain (IASP), is:

"An unpleasant sensory and emotional experience associated with, or resembling that associated with, actual or potential tissue damage."[1]

Although several theoretical frameworks have been proposed to explain the physiological basis of pain, not one theory has been able to exclusively incorporate all aspects of pain perception. The four most influential theories of pain perception include Specificity, Intensity, Pattern and Gate Control theories of pain.[2] However, in 1968, Melzack and Casey described pain as multi-dimensional, where the dimensions are not independent, but rather interactive.[3] The dimensions include sensory-discriminative, affective-motivational and cognitive-evaluate components.

Pain Mechanisms[edit | edit source]

Determining the most plausible pain mechanism(s) is crucial during clinical assessments as this can serve as a guide to determine the most appropriate treatment(s) for a patient.[4] Therefore, criteria upon which clinicians may base their decisions for appropriate classifications have been established through an expert consensus-derived list of clinical indicators. The information below is adapted from research by Smart et al.[5] that classified pain mechanisms as 'nociceptive', 'peripheral neuropathic' and 'central' and outlined both subjective and objective clinical indicators for each. This page also introduces 'nociplastic' pain, which was proposed as a term in 2016.[6]

When considering pain mechanisms, please remember Hickam’s dictum[7] - "a patient can have multiple coincident unrelated disorders."

- Multiple pain mechanisms, as well as psychological and social factors, may be involved at one time. Treatment should focus on the dominant mechanism, as well as any recovery limiting psychological or social factors.

- Pain mechanisms and psychological and social factors can alter and shift with time.

- Pain is based on the patient’s perception of threat. Often the threat is real and sometimes it is not. Understanding pain mechanisms will help you determine when the threat is real.[8]

Nociceptive Pain Mechanism[edit | edit source]

Nociception is defined as:

"1. Pathological process in peripheral organs and tissues. 2. Pain projection into damaged body part or referred pain."[9]

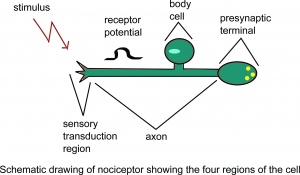

Nociception is a subcategory of somatosensation. Nociception is the neural processes of encoding and processing noxious stimuli.[10] Nociception refers to a signal arriving at the central nervous system as a result of the stimulation of specialised sensory receptors in the peripheral nervous system called nociceptors. Nociceptors are activated by potentially noxious stimuli; as such nociception is the physiological process by which body tissues are protected from damage. Nociception is important for the "fight or flight response" of the body and protects us from harm in our surrounding environment.

Nociceptors can be activated by three types of stimulus within the target tissue - thermal (temperature), mechanical (e.g stretch/strain) and chemical (e.g. pH change as a result of local inflammatory process). Thus, a noxious stimulus can be categorised into one of these three groups. Nociceptive pain is associated with the activation of peripheral receptive terminals of primary afferent neurons in response to noxious chemical (inflammatory), mechanical or ischaemic stimuli.[5][11]

The terms nociception and pain should not be used synonymously, because each can occur without the other. Pain arising from the activation of the nociceptors is called nociceptive pain. Nociceptive pain can be classified according to the tissue in which the nociceptor activation occurred: superficial somatic (e.g. skin), deep somatic (e.g. ligaments/tendons/bones/muscles) or visceral (e.g. internal organs).

For more information, please see: Nociception

Subjective[edit | edit source]

- Clear, proportionate mechanical/anatomical nature to aggravating and easing factors

- Pain associated with and in proportion to trauma, or pathological process (inflammatory nociceptive), or movement/postural dysfunction (ischaemic nociceptive)

- Pain localised to area of injury/dysfunction (with/without some somatic referral)

- Usually resolves rapidly or in accordance with expected tissue healing/pathology recovery times

- Responsive to simple non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs)/analgesics

- Usually intermittent and sharp with movement/mechanical provocation; may be a more constant dull ache or throb at rest

- Pain in association with other symptoms of inflammation (i.e., swelling, redness, heat) (inflammatory nociceptive)

- Absence of neurological symptoms

- Pain of recent onset

- Clear diurnal or 24 hour pattern to symptoms (i.e., morning stiffness)

- Absence of or non-significantly associated with maladaptive psychosocial factors (i.e., negative emotions, poor self-efficacy)

Objective[edit | edit source]

- Clear, consistent and proportionate mechanical/anatomical pattern of pain reproduction on movement/mechanical testing of target tissues

- Localised pain on palpation

- Absence of or expected/proportionate findings of (primary and/or secondary) hyperalgesia and/or allodynia

- Antalgic (i.e., pain relieving) postures/movement patterns

- Presence of other cardinal signs of inflammation (swelling, redness, heat)

- Absence of neurological signs; negative neurodynamic tests (i.e., straight leg raise, Brachial plexus tension test, Tinel’s test)

- Absence of maladaptive pain behaviour

Neuropathic Pain Mechanism[edit | edit source]

The International Association for the Study of Pain (2011) defines neuropathic pain as:

"Pain caused by a lesion or disease of the somatosensory nervous system." [12]

It can result from damage anywhere along the neuraxis: peripheral nervous system, spinal or supraspinal nervous system.

- Central neuropathic pain is defined as "pain caused by a lesion or disease of the central somatosensory nervous system".

- Peripheral neuropathic pain is defined as "pain caused by a lesion or disease of the peripheral somatosensory nervous system".

Neuropathic pain is very challenging to manage because of the heterogeneity of its aetiologies, symptoms and underlying mechanisms.

Peripheral neuropathic pain is initiated or caused by a primary lesion or dysfunction in the peripheral nervous system (PNS) and involves numerous pathophysiological mechanisms associated with altered nerve functioning and responsiveness. Mechanisms include hyperexcitability and abnormal impulse generation and mechanical, thermal and chemical sensitivity.[5][13]

For more information, please see: Neuropathic Pain

Subjective[edit | edit source]

- Pain described as burning, shooting, sharp, aching or electric-shock-like[14]

- History of nerve injury, pathology or mechanical compromise

- Pain in association with other neurological symptoms (i.e., pins and needles, numbness, weakness)

- Pain referred in dermatomal or cutaneous distribution

- Less responsive to simple NSAIDs/analgesics and/or more responsive to anti-epileptic (i.e., Neurontin, Lyrica) or anti-depressant (i.e., Amitriptyline) medication

- Pain of high severity and irritability (i.e., easily provoked, taking longer to settle)

- Mechanical pattern to aggravating and easing factors involving activities/postures associated with movement, loading or compression of neural tissue

- Pain in association with other dysesthesias (i.e., crawling, electrical, heaviness)

- Reports of spontaneous (i.e., stimulus-independent) pain and/or paroxysmal pain (i.e., sudden recurrences and intensification of pain

- Latent pain in response to movement/mechanical stresses

- Pain worse at night and associated with sleep disturbance

- Pain associated with psychological affect (i.e., distress, mood disturbances)

Objective[edit | edit source]

- Pain/symptom provocation with mechanical/movement tests (i.e., active/passive, neurodynamic) that move/load/compress neural tissue

- Pain/symptom provocation on palpation of relevant neural tissues

- Positive neurological findings (including altered reflexes, sensation and muscle power in a dermatomal/myotomal or cutaneous nerve distribution)

- Antalgic posturing of the affected limb/body part

- Positive findings of hyperalgesia (primary or secondary) and/or allodynia and/or hyperpathia within the distribution of pain

- Latent pain in response to movement/mechanical testing

- Clinical investigations supportive of a peripheral neuropathic source (i.e., MRI, CT, nerve conduction tests)

- Signs of autonomic dysfunction (i.e., trophic changes)

Note: Supportive clinical investigations (i.e., MRI) may not be necessary in order for clinicians to classify pain as predominantly “peripheral neuropathic”

Nociplastic Pain Mechanism[edit | edit source]

The International Association for the Study of Pain (2011) defines nociplastic pain as:

“Pain that arises from altered nociception despite no clear evidence of actual or threatened tissue damage causing the activation of peripheral nociceptors or evidence for disease or lesion of the somatosensory system causing the pain”[15]

It is important to note that central sensitisation is not included in the definition of nociplastic pain, but "signs of sensitization are generally present in nociplastic pain conditions"[15] and sensitisation is considered the "major underlying mechanism of nociplastic pain".[15]

For more information, please read: Nociplastic Pain.

Central Sensitisation[edit | edit source]

The International Association for the Study of Pain (2011) defines Central Sensitisation as:

"an increased responsiveness of nociceptors in the central nervous system to either normal or sub-threshold afferent input resulting in: Hypersensitivity to stimuli."[15]

This type of pain does not respond to most medicines and usually requires a tailored programme of care that involves addressing factors that can contribute to ongoing pain (lifestyle, mood, activity, work, social factors).

This pain is initiated or caused by a primary lesion or dysfunction in the central nervous system (CNS).[5][16]

The pain can often be defined as an increased responsiveness of nociceptors in the central nervous system to either normal or sub-threshold afferent input[17] resulting in:

- Hypersensitivity to stimuli.[18]

- Responsiveness to non-noxious stimuli.[12][19]

- Increased pain response evoked by stimuli outside the area of injury, an expanded receptive field.[20]

Watch the 2 minute video below on central sensitisation

For more information please see: Central Sensitisation

Subjective[edit | edit source]

- Disproportionate, non-mechanical, unpredictable pattern of pain provocation in response to multiple/non-specific aggravating/easing factors

- Pain persisting beyond expected tissue healing/pathology recovery times

- Pain disproportionate to nature and extent of injury or pathology

- Widespread, non-anatomical distribution of pain

- History of failed interventions (medical/surgical/therapeutic)

- Strong association with maladaptive psychosocial factors (i.e., negative emotions, poor self-efficacy, maladaptive beliefs and pain behaviours altered by family/work/social life, medical conflict)

- Unresponsive to NSAIDs and/or more responsive to anti-epileptic or anti-depressant medication

- Reports of spontaneous (i.e., stimulus-independent) pain and/or paroxysmal pain (i.e., sudden recurrences and intensification of pain)

- Pain in association with high levels of functional disability

- More constant/unremitting pain

- Night pain/disturbed sleep

- Pain in association with other dysesthesias (i.e., burning, coldness, crawling)

- Pain of high severity and irritability (i.e., easily provoked, taking long time to settle)

- Latent pain in response to movement/mechanical stresses, activities of daily living

- Pain in association with symptoms of autonomic nervous system dysfunction (skin discolouration, excessive sweating, trophic changes)

- Often a history of central nervous system disorder/lesion (i.e., spinal cord injury)

Objective[edit | edit source]

- Disproportionate, inconsistent, non-mechanical/non-anatomical pattern of pain provocation in response to movement/mechanical testing

- Positive findings of hyperalgesia (primary, secondary) and/or allodynia and/or hyperpathia within distribution of pain

- Diffuse/non-anatomic areas of pain/tenderness on palpation

- Positive identification of various psychosocial factors (i.e., catastrophisation, fear-avoidance behaviour, distress)

- Absence of signs of tissue injury/pathology

- Latent pain in response to movement/mechanical testing

- Disuse atrophy of muscles

- Signs of autonomic nervous system dysfunction (i.e., skin discolouration, sweating)

- Antalgic (i.e., pain relieving) postures/movement patterns

Practical Applications[edit | edit source]

Specific classification systems can be useful when diagnosing or classifying pain. The rest of this page focuses on the biopsychosocial model, which encourages clinicians to consider biomedical, psychological and social factors that influence an individual's pain, and the McKenzie Mechanical Diagnosis and Therapy and tissue-based classification systems.

Biomedical Factors[edit | edit source]

When classifying pain, it is important to determine if pain is centrally mediated (e.g. central sensitisation, central nervous system injury (e.g. spinal cord injury, stroke, myelopathy), complex regional pain syndrome), peripherally mediated (e.g. sciatica, carpal tunnel syndrome) or both. Remember that most centrally mediated pain also has a peripherally mediated component.

When considering peripherally mediated pain, first identify if there is a pathoanatomical diagnosis. At this point, it is useful to have multiple hypotheses of pathoanatomical diagnoses. You then use your examination and clinical reasoning to determine the likelihood that the hypothesised pathoanatomic driver of pain is correct. A pathoanatomical diagnosis often indicates the prognosis.

Following this, classify the pain as being either nociceptive or neurogenic. This step helps determine treatment. However, it is important to remember that patients can have more than one type of pain. For example, radicular pain may be associated with nociceptive pain in the spine as well as neurogenic pain in the periphery.[8]

Classification Systems[edit | edit source]

There are a number of classification systems, such as the McKenzie Mechanical Diagnosis and Therapy (MDT) and tissue-based classification systems. These are primarily used to classify nociceptive pain and sometimes neuropathic pain, and are part of the biomedical model.[8]

MDT Classification Systems Overview[8][edit | edit source]

- Dysfunction Syndrome: Commonly associated with tight, weak contractile, articular, and neural tissues which require remodelling to desensitise ischaemic pain (see below). For dysfunction syndrome, exercise prescription is tissue dominant and focused on repeated movements in the direction of the dysfunction or in the direction that reproduces the pain.[21]

- Postural Syndrome: Pain often only present with sustained positions and it tends to improve when the patient changes position. Individuals with postural syndrome may benefit from treatment that focuses on improving motor control.

- Derangement Syndrome: The more common syndrome. The McKenzie institute describes this as pain "caused by a disturbance in the normal resting position of the affected joint surfaces". Often it is a reducible derangement and repeated motions are helpful. If it is an irreducible derangement, it may be necessary to wait for the injury to heal, or surgery may be required.

- Other: This is reserved for diagnoses that cannot be improved with mechanical interventions, e.g. cauda equina syndrome. Non-mechanical interventions are required for individuals within this category.

Tissue-based Classification System[edit | edit source]

It is essential to know whether pain is inflammatory or ischaemic in nature:[8]

- Inflammatory Pain:

- Chemical inflammatory: Pain that is constant.

- Mechanical inflammatory: Pain is intermittent and related to a specific movement.

- Ischaemic Pain: Pain that worsens with activity and resolves at rest - e.g. peripheral arterial disease. The pain is consistent (i.e. comes on at the same point during exercise/walking/activity) and can occur in multiple tissues in the body.

Diurnal Pain Pattern[edit | edit source]

A diurnal pain pattern refers to the changes in pain intensity during the day.[22] The diurnal pain pattern can provide clues about the type of pain.[8]

Examples:[8]

- Pain that is usually worse in the morning, then improves with activity and is painful at night suggests inflammatory pain.[23] Inflammatory pain tends to be present after an activity, at rest or during the night.

- Pain that worsens with activity, but improves with rest suggests ischaemic pain.

Neuropathic Pain[edit | edit source]

- Neural-dependent problems: Neural tissue dysfunction and intraneural mechanical problems requiring treatment to the nerve.

- Container-dependent problems: Neural tissue interface irritation, entrapment, compression site, and extraneural mechanical problems. These are more common than neural-dependent neuropathic pain and require treatment to the 'container' that is causing the symptoms.[8]

As with nociceptive pain, neuropathic pain can be classified using the MDT and tissue-based classification systems.

MDT classification of neuropathic pain:

- Symptoms are provoked by certain sustained postures = postural syndrome

- Repeated spinal motions peripheralise or centralise symptoms = likely derangement syndrome

- Pain is not modified by either changing posture or repeated movements = likely dysfunction syndrome[8]

The pain must then be identified as either neural-dependent or container-dependent.

Tissue-based classification of neuropathic pain:

- Chemical inflammatory neurogenic pain is constant, but its intensity can fluctuate. Ischaemic and mechanical inflammatory neurogenic pain is not constant.

- If pain is quickly provoked with a single movement, it is often mechanical inflammatory pain.

- If pain is only provoked after a number of aggravating movements, it is often ischaemic.[8]

It can be difficult to distinguish between mechanical inflammatory or ischaemic pain. An individual may present with features that suggest both inflammatory pain and ischaemic pain. For instance, ischaemic pain that is treated/loaded too aggressively may lead to an inflammatory reaction.[24] The ischaemic pain may still be present, but the inflammatory pain is now dominant. Once the inflammatory pain reduces, the ischaemic pain becomes dominant again. Thus, the key is to treat, assess response, and then modify accordingly.[25]

Psychological and Social Factors[edit | edit source]

Recovery limiting factors include psychological and social factors.[8] This is particularly true of individuals with central sensitisation or nociplastic pain. There are many different social/psychological factors that may need to be addressed, but some examples are: lack of sleep, stress, depression, anxiety, adverse childhood events, litigation, family, work status, and nutrition. It is, therefore, essential to conduct a detailed examination to identify these factors and consider to what extent these factors are limiting recovery.[26]

References[edit | edit source]

- ↑ Malik NA. Revised definition of pain by ‘International Association for the Study of Pain’: Concepts, challenges and compromises. Anaesthesia, Pain & Intensive Care. 2020 Jun 10;24(5):481-3.

- ↑ Moayedi M, Davis KD. Theories of pain: From specificity to gate control. J Neurophysiol 2013;109:5-12. (accessed 1 April 2014).

- ↑ Melzack R, Casey KL. Sensory, motivational, and central control determinants of pain: a new conceptual model. The skin senses. 1968 Jan 1;1.

- ↑ Graven-Nielsen, Thomas, and Lars Arendt-Nielsen. "Assessment of mechanisms in localized and widespread musculoskeletal pain." Nature Reviews Rheumatology 6.10 (2010): 599.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 5.3 Smart KM, Blake C, Staines A, Doody C. Clinical indicators of 'nociceptive', 'peripheral neuropathic' and 'central' mechanisms of musculoskeletal pain. A Delphi survey of expert clinicians. Man Ther 2010;15:80-7. (accessed 1 April 2014).

- ↑ Fitzcharles MA, Cohen SP, Clauw DJ, Littlejohn G, Usui C, Häuser W. Nociplastic pain: towards an understanding of prevalent pain conditions. Lancet. 2021 May 29;397(10289):2098-110.

- ↑ Jankovic J, Mazziotta JC, Newman NJ, Pomeroy SL. Diagnosis of neurological disease. Bradley and Daroff's Neurology in Clinical Practice. 8th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier. 2022.

- ↑ 8.00 8.01 8.02 8.03 8.04 8.05 8.06 8.07 8.08 8.09 8.10 Rainey N. Pain Mechanisms Overview Course. Plus, 2023.

- ↑ Treede RD. The International Association for the Study of Pain definition of pain: as valid in 2018 as in 1979, but in need of regularly updated footnotes. Pain reports. 2018 Mar;3(2).

- ↑ Loeser JD, Treede RD. The Kyoto protocol of IASP Basic Pain Terminology. Pain. 2008; 137(3): 473–7. doi:10.1016/j.pain.2008.04.025. PMID 18583048

- ↑ Baron R, Binder A, Wasner G. Neuropathic pain: diagnosis, pathophysiological mechanisms, and treatment. The Lancet Neurology. 2010 Aug 1;9(8):807-19.

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 International Association for the Study of Pain. IASP Terminology. Available from: https://www.iasp-pain.org/Education/Content.aspx?ItemNumber=1698#Sensitization.

- ↑ Baron R. Peripheral neuropathic pain: from mechanisms to symptoms. The Clinical journal of pain. 2000 Jun;16(2 Suppl):S12-20.

- ↑ Świeboda P, Filip R, Prystupa A, Drozd M. Assessment of pain: types, mechanism and treatment. Pain. 2013;2(7).

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 15.2 15.3 Nijs J, Lahousse A, Kapreli E, Bilika P, Saraçoğlu İ, Malfliet A, Coppieters I, De Baets L, Leysen L, Roose E, Clark J. Nociplastic pain criteria or recognition of central sensitization? Pain phenotyping in the past, present and future. Journal of clinical medicine. 2021 Jul 21;10(15):3203.

- ↑ Merskey H, Bogduk N. Classification of chronic pain. 2nd ed. Seattle: IASP Press; 1994

- ↑ Louw A, Nijs J, Puentedura EJ. A clinical perspective on a pain neuroscience education approach to manual therapy. J Man Manip Ther. 2017; 25(3): 160-168.

- ↑ Woolf CJ, Latremoliere A. Central Sensitization: A generator of pain hypersensitivity by central neural plasticity. The Journal of Pain 2009; 10(9):895-926

- ↑ Loeser JD, Treede RD. The Kyoto protocol of IASP basic pain terminology. Pain 2008;137: 473–7.

- ↑ Dhal JB, Kehlet H. Postoperative pain and its management. In:McMahon SB, Koltzenburg M, editors. Wall and Melzack's Textbook of pain. Elsevier Churchill Livingstone;2006. p635-51.

- ↑ Mann SJ, Lam JC, Singh P. McKenzie Back Exercises. [Updated 2022 Jul 4]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2022 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK539720/

- ↑ Labrecque, G. Diurnal Variations of Pain in Humans. In: Gebhart, GF, Schmidt, RF, editors. Encyclopedia of Pain. Springer, Berlin, Heidelberg, 2013.

- ↑ Hu S, Gilron I, Singh M, Bhatia A. A scoping review of the diurnal variation in the intensity of neuropathic pain. Pain Medicine. 2022 May;23(5):991-1005.

- ↑ Yam MF, Loh YC, Tan CS, Khadijah Adam S, Abdul Manan N, Basir R. General pathways of pain sensation and the major neurotransmitters involved in pain regulation. International journal of molecular sciences. 2018 Jul 24;19(8):2164.

- ↑ Sumizono M, Yoshizato Y, Yamamoto R, Imai T, Tani A, Nakanishi K, Nakakogawa T, Matsuoka T, Matsuzaki R, Tanaka T, Sakakima H. Mechanisms of Neuropathic Pain and Pain-Relieving Effects of Exercise Therapy in a Rat Neuropathic Pain Model. Journal of Pain Research. 2022 Jul 13:1925-38.

- ↑ O’Sullivan PB, Caneiro JP, O’Keeffe M, Smith A, Dankaerts W, Fersum K, O’Sullivan K. Cognitive functional therapy: an integrated behavioral approach for the targeted management of disabling low back pain. Physical therapy. 2018 May 1;98(5):408-23.