Peripheral Arterial Disease

Original Editors - Students from Glasgow Caledonian University's Cardiorespiratory Therapeutics Project.

Top Contributors - Victoria Michaud, Lucinda hampton, Kim Jackson, Admin, Adam Vallely Farrell, Chris Seenan, Vidya Acharya, 127.0.0.1, Michelle Lee and WikiSysop

Introduction[edit | edit source]

Peripheral artery disease is a common type of cardiovascular disease, which affects 236 million people across the world. It happens when the arteries in the legs and feet become clogged with fatty plaques through a process known as atherosclerosis.

While some people with this disease experience no symptoms, the most classic symptoms are pain, cramps, numbness, weakness or tingling that occurs in the legs during walking – known as intermittent claudication. These problems affect around 30% of people with peripheral artery disease. Intermittent claudication is more common in adults over 50, men and people who smoke.[1]

The management of PAD varies depending on the disease severity and symptom status. Treatment options for PAD include lifestyle changes, cardiovascular risk factor reduction, pharmacotherapy, endovascular intervention, and surgery.[2]

The video below is a good summary of the basics of PAD

Epidemiology[edit | edit source]

Prevalence: 12-14%, 20% of the over 70s in Western populations[4].

Smoking increases the risk of developing PAD fourfold and has the greatest impact on disease severity. Compared to non-smokers, smokers with PAD have shorter life spans and progress more frequently to critical limb ischemia and amputation. Additional risk factors for PAD include diabetes, hyperlipidemia, hypertension, race, and ethnicity.

Etiology[edit | edit source]

Peripheral artery disease is usually caused by atherosclerosis. Other causes may be inflammation of the blood vessels, injury, or radiation exposure.[2]

Risk factors: Smoking, Hypertension, Diabetes, High cholesterol, Increasing age (especially after reaching 50 years of age), Family history of peripheral artery disease, Heart disease or Stroke, High levels of homocysteine (a protein component that helps build and maintain tissue).[2]

History and Presentation[edit | edit source]

The most characteristic symptom of PAD is claudication which is a pain in the lower extremity muscles brought on by walking and relieved with rest.

- Although claudication has traditionally been described as cramping pain, some patients report leg fatigue, weakness, pressure, or aching.

- Symptoms during walking occur in the muscle group one level distal to the artery narrowed or blocked by PAD. eg Patients with aortoiliac artery occlusive disease have symptoms in the thigh and buttock muscles, patients with femoropopliteal PAD have symptoms in their calf muscles.

- Some patients with mild or moderate PAD rarely sustain a walking pace that increases the blood flow requirement of the lower extremity muscles. By being physically inactive, these patients avoid the supply-demand mismatch that triggers claudication symptoms.

- Other patients with PAD have muscle discomfort when they walk but fail to report these symptoms because they attribute them to the natural consequences of aging.

Patients with severe PAD can develop ischemic rest pain.

- These patients do not walk enough to claudicate because of their severe disease.

- They complain of burning pain in the soles of their feet that is worse at night. They cannot sleep due to the pain and often dangle their lower leg over the side of the bed in an attempt to relieve their discomfort. The slight increase in blood flow due to gravity temporarily diminishes the otherwise intractable pain.

Clinical Manifestations[edit | edit source]

Image: A 71-year-old diabetic male smoker with severe peripheral arterial disease presented with a dorsal foot ulceration (2.5 cm X 2.4cm) that had been chronically open for nearly 2 years.

- Non-healing wounds on legs or feet

- Unexplained leg pain

- Pain on walking that resolves when stopped

- Pain in foot at rest made which worsens with elevation

- Ulcers

- Gangrene

- Dry skin

- Cramping

- Aching[5]

Evaluation[edit | edit source]

Making the diagnosis of PAD should factor in the patient’s history, physical exam, and objective test results. Key points in the history include an accurate assessment of:

- Patient’s walking ability[2]. For Objective Measures see below, under physiotherapy

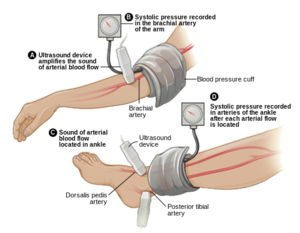

- On physical exam, patients with PAD may have diminished or absent lower extremity pulses. This finding can be confirmed with the Ankle Brachial Pressure Index (ABI), a simple and inexpensive test that measures the ratio between blood pressure in the legs to the blood pressure in the arms.[6] An ABI of 0.9- 1.0 is normal, 0.70-0.89 is a mild disease, 0.40- 0.69 is a moderate disease, and less than .40 is a severe PAD[6]. When measuring for ABI, make sure the patient is calm and in a rested position [5].

- Other investigations include:

- Doppler US: initial investigation; assess flow and atherosclerotic plaque

- Angiography (CT, MR, DSA): direct imaging of the vessels and runoff.[4]

Management[edit | edit source]

Management strategies for PAD attempt to achieve two distinct goals: lower cardiovascular risk and improve walking ability. All patients with PAD, regardless of the presence or absence of symptoms, have an increased risk of stroke, myocardial infarction, and thrombosis compared to patients without arterial disease. These cardiovascular events probably account for the shorter life expectancy of patients with PAD. Therefore, all patients diagnosed with PAD should undertake lifestyle changes aimed at lowering their cardiovascular risk profile. Key targets for lifestyle changes include quitting smoking, lowering cholesterol, and controlling hypertension and diabetes.

Other treatment involves:

Medical therapy: involves the use of cilostazol, a medication that promotes vasodilation and suppresses the proliferation of vascular smooth muscle cells; the use of statins to improve the atherosclerotic disease; antihypertensives.[2][4]

Revascularisation

- Balloon angioplasty or stent placement provides a minimally invasive, percutaneous treatment option for patients with PAD symptoms that do not respond to exercise or medical therapy

- Surgical options for PAD include bypass grafts to divert flow around the blockage or endarterectomy to segmentally remove the obstructive plaque.[2]

Physiotherapy Management[edit | edit source]

The least invasive and most appropriate treatment for PAD conducted by Physiotherapists would be by prescribing an exercise program. Exercise therapy involves walking until reaching pain tolerance, stopping for a brief rest, and walking again as soon as the pain resolves. These walking sessions should last 30 to 45 minutes, 3 to 4 times per week for at least 12 weeks. Despite being more effective, supervised exercise programs for PAD are not usually covered by insurance companies

A 2018 review of the best exercise prescription for PAD summarised their findings thus

- Supervised treadmill exercise improves treadmill walking performance in patients with PAD.

- Supervised treadmill exercise has greater benefit on treadmill walking performance than home-based walking exercise.

- Home-based walking exercise interventions that involve behavioral techniques are effective for functional impairment in people with PAD and improve the 6-min walk distance more than supervised treadmill exercise.

- Upper and lower extremity ergometry improve walking performance in patients with PAD and improve peak oxygen uptake.

- Lower extremity resistance training can improve treadmill walking performance in PAD, but is not as effective as supervised treadmill exercise.[7]

The optimal exercise program for PAD recommended by the American Heart Association states the following : Exercise Prescription for Supervised Exercise Treadmill Training in Patients With Claudication

- Modality Supervised Treadmill Walking

- Intensity 40%–60% maximal workload based on baseline treadmill test or workload that brings on claudication within 3–5 min during a 6-MWT

- Session duration 30–50 min of intermittent exercise; goal is to accumulate at least 30 min of walking exercise

- Claudication intensity Moderate to moderate/severe claudication as tolerated

- Work-to-rest ratio Walking duration should be within 5–10 min to reach moderate to moderately severe claudication followed by rest until pain has dissipated (2–5 min)

- Frequency 3 times per week supervised

- Program duration At least 12 wk

- Progression Every 1–2 wk: increase duration of training session to achieve 50 min. As individuals can walk beyond 10 min without reaching prescribed claudication level, manipulate grade or speed of exercise prescription to keep the walking bouts within 5–10 min

- Maintenance Lifelong maintenance at least 2 times per week

Based on currently available evidence. Exercise prescription should be individualized to each patient as tolerated. 6-MWT indicates 6-minute walk test. [8]

A recent research study showed that Nordic walking training improved the gait pattern of patients with PAD remarkably and caused a significant increase in the absolute claudication distance and total gait distance. The combined training of Nordic walking with the isokinetic resistance training of the lower extremities muscles (NW + ISO) increased the amplitude of the general center of gravity oscillation to the greatest extent. However, only treadmill training had little effect on the gait pattern. Hence, Nordic walking can be used to rehabilitate patients with PAD as a form of gait training[9].

Outcome Measures[edit | edit source]

- 6 Minute Walk Test (MWT)

- Timed Up and Go Test (TUG)

- EQ-5D

- Incremental shuttle walk test (ISWT)[10]

Prevention[edit | edit source]

According to Warren[11] there are several methods one can prevent PAD. Firstly, help change the patient's lifestyle by educating them on the risk factors and the effects PAD. If the patient smokes cigarettes, it is important to address the issue and promote cessation. Those who consume a high fat diet have a higher chance of being diagnosed with PAD, thus one should encourage a reduced fat diet as a strong prevention method. Along with diet, it is important to live an active lifestyle. By being active and working up to the general standards of physical activity per week will allow a decrease in weight along with a decrease in risk of PAD.

Prognosis[edit | edit source]

Even with treatment, the prognosis of PAD is generally guarded. If the patient does not change his/her lifestyle, the disease is progressive. In addition, most patients with PAD also have coexistence of cerebrovascular or coronary artery disease, which also increases the mortality rate. The outcomes in women tend to be worse than in men, chiefly because of the small diameter of the arteries. In addition, females are more likely to develop complications and embolic events.[2]

Conclusions[edit | edit source]

Highlights from the 2016 AHA advice regarding PAD management

- Patients with peripheral artery disease (PAD) should be on a program of guideline-directed medical therapy (including antiplatelet drugs that thin blood and statins to lower cholesterol) and should participate in a structured exercise program.

- Restoring blood flow to the legs through vascular procedures is appropriate for many patients with severe symptoms due to PAD.

- Eliminating exposure to all tobacco – including second-hand smoke – is highly recommended for patients with PAD.[12]

References[edit | edit source]

- ↑ The Conversation Walking can relieve leg pain in people with peripheral artery disease Available: https://theconversation.com/walking-can-relieve-leg-pain-in-people-with-peripheral-artery-disease-151240(accessed 6.6.2021)

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 2.4 2.5 2.6 Zemaitis MR, Boll JM, Dreyer MA. Peripheral arterial disease. StatPearls [Internet]. 2020 Jul 6.Available :https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK430745/ (accessed 6.6.2021)

- ↑ American Heart Association PAD What is it? Available from: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=XTSgpiPqIbk (last accessed 7.9.2019)

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 Radiopedia PAD Available:https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK430745/ (accessed 6.6.2021)

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 NICE National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Lower limb peripheral arterial disease: diagnosis and management, 2012. https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg147/chapter/guidance#management-of-intermittent-claudication (accessed 9 May 2015)

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 Mahameed, AA, Bartholomew, JR, Disease of Peripheral Vessels. In: Topol, EJ, editor. Textbook of Cardiovascular Medicine. 3rd ed. New York: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 2007, p.1531-1537

- ↑ McDermott MM. Exercise rehabilitation for peripheral artery disease: a review. Journal of cardiopulmonary rehabilitation and prevention. 2018 Mar;38(2):63. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5831500/ (last accessed 6.9.2019)

- ↑ Diane Treat-Jacobson, Mary M. McDermott, Ulf G. Bronas et al.Optimal Exercise Programs for Patients With Peripheral Artery Disease: A Scientific Statement From the American Heart Association. AHA Journal Vol. Circulation.130 No.4 Available from: https://ahajournals.org/doi/10.1161/CIR.0000000000000623 (last accessed 7.9.2019)

- ↑ W Dziubek, M Stefańska, K Bulińska, K Barska Journal of Clinical …, 2020 - mdpi.comEffects of Physical Rehabilitation on Spatiotemporal Gait Parameters and Ground Reaction Forces of Patients with Intermittent Claudication

- ↑ Dixit S, Chakravarthy K, Reddy RS, Tedla JS. Comparison of two walk tests in determining the claudication distance in patients suffering from peripheral arterial occlusive disease. Advanced biomedical research. 2015;4.Available: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4513323/(accessed 6.6.2021)

- ↑ Warren, E. Ten things the practice nurse can do about peripheral arterial disease. Practice Nurse 2013; 43; 12: 14-18.

- ↑ Newsroom. New peripheral artery disease guidelines emphasize medical therapy and structured exercise 13.11. 2016 Available from: https://newsroom.heart.org/news/x-new-peripheral-artery-disease-guidelines-emphasize-medical-therapy-and-structured-exercise (last accessed 7.9.2019)