Surgery and General Anaesthetic

Original Editors - Students from Glasgow Caledonian University's Cardiorespiratory Therapeutics Project.

Top Contributors - Bo Lian Ho Sing, Lucinda hampton, Erin Froude, Michelle Lee, Chris Seenan, Kim Jackson, 127.0.0.1, Admin, George Prudden, Adam Vallely Farrell and Karen Wilson

Definition[edit | edit source]

“Surgery” means a procedure performed for the purpose of structurally altering the human body by incision or destruction of tissues and is part of the practice of medicine for the diagnostic or therapeutic treatment of conditions or disease processes.

- Surgery can be done by any instruments causing localized alteration or transportation of live human tissue, which include lasers, ultrasound, ionizing radiation, scalpels, probes, and needles.

- During surgery the tissue can be cut, burned, vaporized, frozen, sutured, probed, or manipulated by closed reduction for major dislocation and fractures, or otherwise altered by any mechanical, thermal, light-based, electromagnetic, or chemical means.

- Injection of diagnostic or therapeutic substances into body cavities, internal organs, joints, sensory organs, and the central nervous system is also considered to be surgery[1]

Anaesthetics

An anaesthetic is a drug or agent that produces a complete or partial loss of feeling. There are three kinds of anaesthetic: general, regional and local.

General Anaesthetic[edit | edit source]

A qualified anaesthetist administers the general anaesthetic (intravenously or by gas mask, or both).

- After a few seconds the client becomes unconscious.

- The anaesthetist then inserts a small tube connected to a ventilator into the airway (an endotracheal tube is usually used) or a laryngeal mask.

- The anaesthetist controls the length of time patient is asleep, and constantly monitors pulse, breathing and blood pressure.

- If necessary, the anaesthetist will administer intravenous fluids before, during and after surgery.

- Once the surgery is over other drugs may be injected that will reverse the effect of the anaesthetic and any other drugs used during the operation (such as muscle relaxant).

Complications from general anaesthetic are rare. It is estimated that around one in every 10,000 people undergoing general anaesthetic die from an unforeseen complication, such as an allergic reaction or a heart attack.[2]

Image 2: Examples of anaesthetic breathing systems. From top to bottom: a Mapelson C system; a Mapelson E system (also known as Ayre's T-piece), to which a Venturi valve has been fitted so as to reduce the delivered oxygen concentration; and a Mapelson F system.

Regional and Local Anaesthetics[edit | edit source]

Depending on the type of surgery, alternatives to general anaesthetic can include:

- Regional anaesthetic – or ‘nerve block’. eg, a woman giving birth by caesarean section may have an epidural (an injection into the spine that numbs the body from the waist down).

- Local anaesthetic – anaesthetic is injected into the immediate area to be operated on.eg a dentist may inject local anaesthetic into the gum before removing a tooth.

Surgical Epidemiology[edit | edit source]

Surgical approaches are receiving increasing attention as a way to solve many global public health problems. Surgery can play a vital role in helping countries meet their Millennium Development Goals 4, 5 and 6.3

What is surgical epidemiology? Unfortunately, there is not yet an agreed definition for this field. Definitional issues and challenges are greater in developing countries, where WHO wish to encourage the debate on surgical epidemiology. To improve the evidence base for surgery as a cost-effective intervention in developing countries, epidemiologists and surgeons must work together to agree upon a vocabulary and set of definitions. As the saying goes, the eye cannot see what the mind does not know.[3]

Advances in Surgery[edit | edit source]

The 20th and 21st centuries witnessed several new surgical technologies to supplement the techniques of manual incision.

- Lasers became widely used to destroy tumours and other pigmented lesions, some of which are inaccessible by conventional surgery. They are also used to surgically weld detached retinas back in place and to coagulate blood vessels to stop them from bleeding.

- Stereotaxic surgery uses a three-dimensional system of coordinates obtained by X-ray photography to accurately focus high-intensity radiation, cold, heat, or chemicals on tumours located deep in the brain that could not otherwise be reached.

- Cryosurgery uses extreme cold to destroy warts and precancerous and cancerous skin lesions and to remove cataracts

- Some traditional techniques of open surgery were replaced by the use of a thin flexible fibre-optic tube equipped with a light and a video connection; the tube, or endoscope, is inserted into various bodily passages and provides views of the interior of hollow organs or vessels. Accessories added to the endoscope allow small surgical procedures to be executed inside the body without making a major incision.[4]

Major Categories of Surgery[edit | edit source]

There are four major categories of surgery:

- Wound treatment: centred on procuring good healing and the avoidance of infection

- Extirpative surgery: involves the removal of diseased tissue or organs. Cancer surgery usually falls into this category, with mastectomy, cholecystectomy (removal of the gallbladder), and hysterectomy among the most frequent procedures.

- Reconstructive surgery: deals with the replacement of lost tissues, whether from fractures, burns, or degenerative-disease processes, and is especially prominent in the practice of plastic surgery and orthopedic surgery eg the use of metal in reconstructing hip joints (THR) and the use of plastic valves to replace heart valves.

- Transplantation surgery: the use of organs transplanted from other bodies to replace diseased organs in patients. Kidneys are the most commonly transplanted organs.[4]

Global Surgery: Low and Middle Income Countries[edit | edit source]

Remarkable gains have been made in global health in the past 25 years, but progress has not been uniform.

- Mortality and morbidity from common conditions needing surgery have grown in the world's poorest regions, both in real terms and relative to other health gains. At the same time, development of safe, essential, life-saving surgical and anaesthesia care in low-income and middle-income countries (LMICs) has stagnated or regressed.

- In the absence of surgical care, case-fatality rates are high for common, easily treatable conditions including appendicitis, hernia, fractures, obstructed labour, congenital anomalies, and breast and cervical cancer.[5]

Post-Operative Pulmonary Complications (PPCs)[edit | edit source]

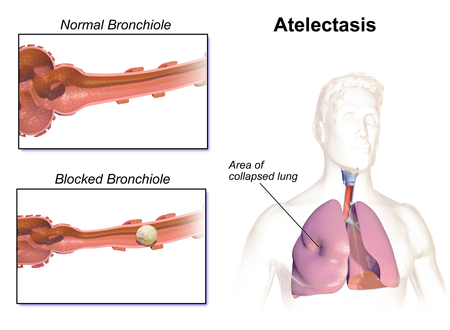

Post-operative pulmonary complication is an umbrella term of adverse changes to the respiratory system occurring immediately after surgery. The most common presentations include an altered function of respiratory muscles, reduced lung volume, respiratory failure and atelectasis.[6]

See Post-Operative Pulmonary Complication

Risk factors associated with the risk of post-operative pulmonary complications

- Obesity

- Smoking - increases mucus production and is more difficult to clear, resulting in development of COPD and PPC

- COPD & Asthma

- Age - older aged people have deteriorated lung function and this is exacerbated with anaesthetics

- Poor nutrition - if 70% less than ideal body weight, can have weak respiratory muscles which can lead to protein depletion when undergoing anaesthetic, resulting in an increased risk of PPC

- Type of surgery - closer to the diaphragm, the greater the risk of a complication

- Use of oxygen - dry cold gases entering a warm humidifed area can result in increase in sputum viscosity and decrease mucociliary function which can increase bronchial secretions.

Investigations[edit | edit source]

Prior to surgery, the patient must undergo a pre-operative assessment. This involves seeing a nurse or doctor who will ask the patient questions about their health, medical history, advise the patient on what to do before the surgery and where to report on the day [7]. They may also carry out some tests, such as, blood pressure (BP) and respiratory rate (RR) so that when assessing the patient after surgery, they have baseline measurements to compare against. The pre-assessment will highlight any contra-indications that could postpone the surgery procedure [7].

Surgery and general anaesthetic can lead to postoperative pulmonary complications so it is crucial that patients are monitored.

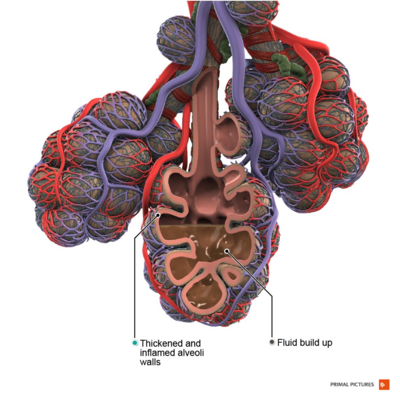

Anaesthesia can have an effect on lung mechanics, lung defences and gas exchange, therefore a chest x-ray will help identify if there is a lung collapse or any consolidation[8].

Investigations used for monitoring the patient after surgery include: chest x-rays, BP, HR, RR, ABG's .

- A CT scan can also identify consolidation and atelectasis[9].

- Postoperative hypoxaemia may be present, thus an analysis of an arterial blood sample allows a physiotherapist to monitor deterioration and identify respiratory failure[10].

- Another possible effect of anaesthesia is an alteration in mucociliary clearance. This can be monitored using auscultation to determine where the secretions are (broad).

- Blood pressure can help determine cardiovascular status of the patient[10].

- Other observations could be heart rate, respiratory rate and temperature as these can all be altered if the patient has an infection[9].

Surgical Monitoring[edit | edit source]

Contemporary surgical therapy is greatly helped by monitoring devices that are used during surgery and during the postoperative period.

- Blood pressure and pulse rate are monitored during an operation because a fall in the former and a rise in the latter give evidence of a critical loss of blood.

- Other items monitored are the heart contractions as indicated by electrocardiograms; tracings of brain waves recorded by electroencephalograms, which reflect changes in brain function; the oxygen level in arteries and veins; carbon dioxide partial pressure in the circulating blood; and respiratory volume and exchange.

- Intensive monitoring of the patient usually continues into the critical postoperative stage.[4]

Image 4: Anesthesia machine

Signs & Symptoms Present Post Surgery[edit | edit source]

- Immobile - patient may have a catheter and be on intravenous lines, have chest drains or a stoma bag, feel nausea from the anaesthetic or if they had have had an epidural, motor blocks may be hampering the patients ability to move around after surgery.

- Drowsiness

- Nausea

- Pain - coming round from being under anaesthetic, the patient may feel sudden pain and anxiety. This may also affect their inability to breathe deeply as their breathing tends to change to shallow and rapid breathing, reducing their functional residual capacity, resulting in atelectasis.

- Lung collapse - during surgery functional residual capacity can also decrease and it is thought this is due to the relaxation of the muscles of the chest wall, a decrease in mucociliary function, cephalad movement of the diaphragm and an increase in thoracic blood volume. This results in atelectasis and blockage of the bronchioles due to secretions and then could result in further collapse. Lung collapse can occur within 15 minutes of surgery and can last up to 4 days after surgery. if this is not seen to, this increases the risk of infection.

- Diaphragmatic dysfunction - may not contract sufficiently for up to 7 days after

Physiotherapy and Other Management[edit | edit source]

Pre-operative Physiotherapy[8]

Trying to see a patient before surgery can be beneficial, however, it can also be difficult if its an emergency or could be due to time constrictions with the patients, particularly within the NHS.

A pre-operative assessment may include:

- an explanation of the role of the physiotherapist within the team

- the possible risks of surgery and the effects of general aneasthesia

- what will happen after the surgery

Some of these benefits to seeing a physiotherapist pre-operatively are:

- may reduce the patient's anxiety levels

- confidence could be gained

- the patient will have more knowledge on what is entailed before,during and after the surgery and how they may feel afterwards

- can prevent the risk of developing post-operative pulmonary complications

Post-operative Physiotherapy

The main problems found on assessment of a patient who has had major surgical procedure is reduced lung volume[8]. This could result in impaired gas exchange and airway clearance[8]. Other cardiovascular and respiratory effects are reduction in functional residual capacity, PaO2, VO2Max, cardiac output and stroke volume, and an increase in HR[8]. Thus the aim of the physiotherapist is to try and improve these problems. From the post-operative assessment a treatment plan will be developed.

- Mobilisation - important component that will improve lung volume, improve circulation thus helping remove secretions, decrease their stay in the hospital and will make it easier for the patient to remove secretions. Examples: walking around their bed or along the corridor. This can be progressed to marching on the spot and moving from their bed to the chair.

- Positioning - sitting up and changing positions regularly can help improve ventilation and removing secretions.

- deep breathing exercises - include thoracic expansion exercises, diaphragmatic breathing & maximal inspiration[8]. Can help reinflate the collapsed lung[8].

- Appropriate airway clearance techniques can be implemented, such as, active cycle of breathing techniques and autogenic drainage [9]. With surgery, more emphasis is on the deep breathing component rather than the forced expiratory manoeuvres to avoid pain and discomfort for the patient[8].Holding the breath and sniffing at the end of inspiration will help expand the lungs.

- Continuous Positive Airway Pressure (CPAP) - assist with hypoxaemia, reduce RR & minute ventilation and also through to increase vital capactiy[8].

- Intermittent Positive Pressure - help improve lung volume and sputum retention

- Incentive spirometry - used to stimulate the patient to perform deep breathing exercises[8].

Image 5: Incentive spirometer that encourages deep breathing after operations

Management of Post-operative Pain

Pain after surgery can have a major effect on the patients recovery. Some of the effects are:

- ineffecitve ventilation

- poor cough

- inability to take deep breaths and sigh

- result in atelectasis, hypoxaemia and respiratory distress

- poor sleep

- delayed hospital charge

If their pain can be managed, this may result in a reduced length of stay in the hospital, reduce their length of rehabilitation and their rehabilitation will be more efficient[8].

Pain can be reduced through medication, education, careful handling and relaxation techniques[9] .

Different ways to administer drugs are:

- oral - codeine etc. they will sensitise nociceptor nerve endings and can reduce fever

- intra-muscular - morphine

- intra-venous - morphine, ketamine

- patient controlled analgesia - pethidine, fentanyl. Common method used to improve pain releif as it is not continuous so could prevent the risk of respiratory depression

- epidural - morhine, fentanyl

- peripheral blocks - bupivacaine. can block propogation of action potentials by blocking sodium channels

it is important that the physiotherapist is working with the patient when they are in least pain so they can get the best treatment, therefore it is recommended that the physiotherapist sees the patient 30 minutes after they have taken their medication.

Prevention of PCCs[edit | edit source]

Physiotherapists play a large part in prevention of PCC's see below links:

Physical Activity Pre and Post Surgery, Post-Operative Pulmonary Complication, and Spirometry

Older Persons and Surgery[edit | edit source]

Between 1960 and 1994, the population of those 85 years and older in the United States grew 274%. Similarly, the fastest-growing sector of surgical patients older than 65 years is those older than 85 years. These figures are critical because elderly persons have the highest mortality in the adult surgical population. Elderly persons experience normal physiological changes associated with aging in all of their solid organ systems. Together, these changes lead to a diminished physiological reserve.

- Patients with advanced age have the highest mortality rate within the adult surgical population.

- A major risk factor for perioperative mortality is considered to be advanced age.

- The effects of postoperative stresses are more detrimental to some organ systems than others.eg. Myocardial infarctions have been reported as the leading cause of postoperative death among 80-year-old patients; Pulmonary complications, including pneumonia, hypoventilation, hypoxia, and atelectasis, are reported to occur in 2% to 10% of elderly patients; Cerebrovascular-related mortality in elderly patients undergoing urological procedures was reported to be 0.05%; Postoperative delirium varies between 5% and 61%, but only 1% of patients have persistent symptoms[11]

Image 3: Pneumonia Alveoli

Should we offer surgery to everyone?

- The practice of surgery and medicine, especially when considering older adults, needs to remain focused on individualised patient care. Decisions should be based on medical appropriateness of treatment combined with a patient’s goals and values.

- To do this we need to train clinicians in shared decision-making and how to have these often difficult discussions. The goal is to have clinicians who are able to explore a patient’s values and preferences around outcomes, effectively communicate individualised information about options, benefits and harms, and then come to a decision together[12].

Abdominal Surgery[edit | edit source]

Patients undergoing upper abdominal surgery are at higher risk of post-operative pulmonary complications than cardiothoracic, lower abdominal or peripheral surgery[13].

- For upper abdominal surgery, once anaesthetized, respiratory suppression is caused by paralysis leading to the use of mechanical ventilation.

- Functional Residual Capacity (FRC) drops as soon as the general anaesthetic enters the body; this reduction in FRC is an important factor in the possible development of post-operative complications, as is the length of time FRC is maintained at a lower volume[13].

- During major abdominal surgery, the patient is lying supine. Adults lying supine see a drop in FRC by 1L[13].

References[edit | edit source]

- ↑ American college of Surgeons American College of Surgeons Definition of Surgery Legislative Toolkit Available from: https://www.facs.org/-/media/files/advocacy/state/definition-of-surgery-legislative-toolkit.ashx(accessed 18.2.2021)

- ↑ Better health Channel General anaesthetics Available from: https://www.betterhealth.vic.gov.au/health/conditionsandtreatments/general-anaesthetics (accessed 18.2.2021)

- ↑ Thind A, Mock C, Gosselin RA, McQueen K. Surgical epidemiology: a call for action. Bulletin of the World Health Organization. 2012;90:239-40.Available from: https://www.who.int/bulletin/volumes/90/3/11-093732/en/(accessed 18.2.2021)

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 Britanicca Surgery Available from:https://www.britannica.com/science/surgery-medicine (accessed 18.2.2021)

- ↑ The Lancet, AUGUST 08, 2015 Global Surgery 2030: evidence and solutions for achieving health, welfare, and economic development available from:https://www.thelancet.com/journals/lancet/article/PIIS0140-6736(15)60160-X/fulltext (last accessed 18.2.2021)

- ↑ Miskovic A, Lumb AB. Postoperative pulmonary complications. BJA: British Journal of Anaesthesia. 2017 Mar 1;118(3):317-34.Available from:https://slideplayer.com/slide/16089846/ (accessed 19.2.2021)

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 NHS. Going into hospital. http://www.nhs.uk/NHSEngland/AboutNHSservices/NHShospitals/Pages/going-into-hospital.aspx#assessment (accessed 29th May 2015).

- ↑ 8.00 8.01 8.02 8.03 8.04 8.05 8.06 8.07 8.08 8.09 8.10 Denehy, L. Surgery for adults. In: Pryor, J.A, Prasad, S.A (eds.) Physiotherapy for Respiratory and Cardiac Problems. United Kingdom: Churchill livingstone; 2008. p. 397-439.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 9.2 9.3 Hough, A. Physiotherapy in Respiratory and Cardiac Care - an evidence-based approach. (4th ed.). Singapore: Andrew Ashwin; 2014.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 Broad, M. Cardiorespiratory Assessment of the Adult Patient: a Clinician's Guide. Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone; 2012

- ↑ Aalami OO, Fang TD, Song HM, Nacamuli RP. Physiological features of aging persons. Archives of Surgery. 2003 Oct 1;138(10):1068-76.Available from:https://jamanetwork.com/journals/jamasurgery/fullarticle/395665 (accessed 18.2.2021)

- ↑ The conversation Surgery rates are rising in over-85s but the decision to operate isn’t always easy Available from:https://theconversation.com/surgery-rates-are-rising-in-over-85s-but-the-decision-to-operate-isnt-always-easy-116814 (accessed 19.2.2021)

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 13.2 Blanchard M. Pre-operative risk assessment to predict post-operative pulmonary complications in upper abdominal surgery: a literature review. Association of Chartered Physiotherapists in Respiratory Care. 2006;38:32-40.