Fracture

Top Contributors - Esraa Mohamed Abdullzaher, Naomi O'Reilly, Kalyani Yajnanarayan, Lucinda hampton, Khloud Shreif, Kim Jackson, Aminat Abolade, Claire Knott and Abbey Wright

Definition[edit | edit source]

A fracture is a discontinuity in a bone (or cartilage) resulting from mechanical forces that exceed the bone's ability to withstand them.[1] Fractures can occur in a variety of methods:

- A normal bone subjected to acute overwhelming force, usually in the setting of trauma

- Weakened bone from a focal lesion (e.g. metastasis, or bone cyst), known as pathological fractures.

- Weakened bone due to metabolic abnormalities (e.g. osteoporosis) or less frequently, genetic abnormalities (e.g. osteogenesis imperfecta). Resulting in insufficiency fractures.

- Chronic application of abnormal stresses (e.g. running), resulting in microfractures and eventually, macroscopic failure (fatigue fractures).

Together, insufficiency and fatigue fractures are often grouped together as stress fractures.

Location[edit | edit source]

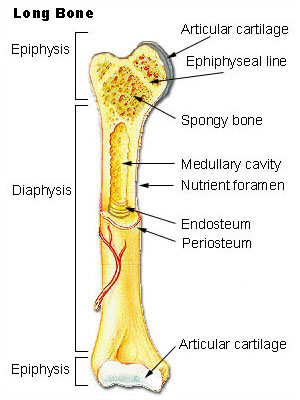

Type of Bone Fractured[2]

- long bone (femur, tibia, fibula and humerus)

- short bone (carpal bones)

- flat bone (scapulae, ribs)

- Sesamoid bone (patella)

- Irregular bone (vertebrae and skull)

Part of Bone Fractured

- Epiphysis

- Physis

- Metaphysis

- Diaphysis

- Specific Features within a bone (tubercle, epicondyle)

Types of Bone Fracture[edit | edit source]

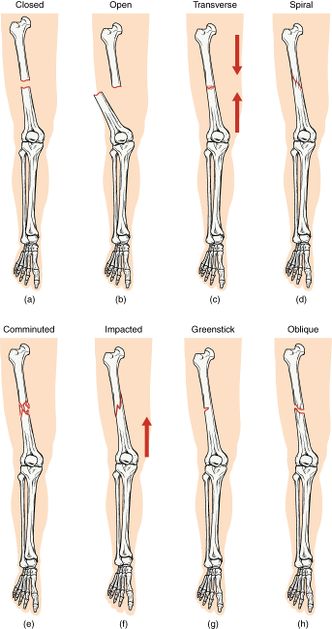

In general, there are many different classification systems used for fractures which fall within a set number of patterns:[2]

- Complete: Extends all the way across the bone (most common)

- Incomplete: does not cross the bone completely (usually encountered in children)

- Non-Displaced / Stable: Fractured ends of the bone line up

- Displaced / Unstable: Fractured portions of bone are separated or misaligned.

- Closed / Simple: Bone has not pierced the skin

- Open / Compound: Skin has been pierced or punctured by the bone or by a blow that breaks the skin at the time of the fracture. The bone or may not be visible.

- Transverse: Fracture is in a straight line across or perpendicular to axis of the bone

- Oblique: Fracture is orientated obliquely across the bone

- Spiral: Fracture spirals around the bone, or a helical fracture path usually in the diaphysis of long bones, common in twisting injuries.

- Stress: Small crack or severe bruising within a bone

- Comminuted: Fracture is in three or more pieces with fragments present at the site

- Compression: Bone is crushed causing the fractured bone to be wider or flatter in appearance

- Segmental: Same bone is fractured in two places so there is ‘floating’ segment of bone

- Bowing: Incomplete fracture of long bone in infants/children due to forces in the axial load[3].

- Buckle Fracture: Due to direct axial load, the cortex is buckled, often in the distal radius

- Greenstick Fracture: Fracture in a young, soft bone in which the bone bends and the cortex is broken, but only on one side[1]

Pathophysiology of Bone Healing[edit | edit source]

The pathophysiological sequence of events that occur following a fracture for bone healing can be divided into three main phases[2][4][5]

- Inflammatory Phase

- Reparative Phase

- Remodelling Phase

Phase 1 - Inflammatory Phase (Hours - Days)[edit | edit source]

Immediately at the time of fracture, the space between the ends of the fracture is filled with blood, forming a haematoma. This prevents additional bleeding and provides structural and biochemical support for the influx of inflammatory cells.

The inflammatory reaction results in the release of cytokines, growth factors and prostaglandins, all of which are important in healing. The fibroblasts, chondroblasts and the ingrowth of capillaries is then infiltrated by fibrovascular tissue. This forms a matrix for bone formation and primary callus. Phase 1 takes approximately a week, forming a primary callus which is non-mineralized.[2]

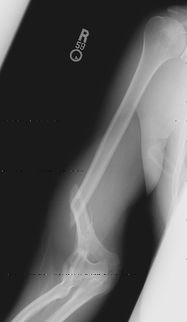

This is not readily visible on radiography.

Phase 2 - Reparative Phase (Days - Weeks)[edit | edit source]

Over the next few weeks, this primary callus is transformed into a bony callus by the activation of osteoprogenitor cells. These cells lay down woven bone which stabilises the fracture site. [2]

Soft callus is organised and remodelled into hard callus over several weeks. Soft callus is plastic and can easily deform or bend if the fracture is not adequately supported. Hard callus is weaker than normal bone but is better able to withstand external forces and equates to the stage of "clinical union", i.e. the fracture is not tender to palpate or with movement.

This can be seen on radiographs within 7-10 days after injury.

Phase 3 - Remodelling Phase (Months to Years)[edit | edit source]

The remodelling phase is the longest phase and may last several years. [2]

This phase represents the gradual formation of compact cortical bone with greater biomechanical properties. This allows for the reduction of the width of the callus.

During remodelling, the healed fracture and surrounding callus responds to activity, external forces, functional demands and growth. Bone (external callus) which is no longer needed is removed and the fracture site is smoothened and sculpted.

Remodelling can result in almost perfect healing, however, where the alignment of the fracture site is not perfect, a residual deformity may remain.[1]

Complications[edit | edit source]

Many of the aforementioned fracture types can also go on to have additional complications (and many associated soft tissue injuries). See Fracture Complications

- Acute Compartment Syndrome is common in fractures of the forearm.

- Fat embolism syndrome (a piece of fat that is released into the blood vessels causing blockage of blood flow) [7] that is most commonly associated with long bone and pelvic fracture[8]

- Osteomyelitis of bone in response to infection.

- Healing complications: malunion, delayed union or non-union. [9]

- Avascular Necrosis

- Fracture Blisters

- Compound Fracture: extending through the skin

- Joint Involvement: intracapsular, articular, dislocation. This can lead to osteoarthritis in the long term.

Clinical Features of Fracture[edit | edit source]

Clinical features vary depending on the cause of injury, its nature and the patient's level of consciousness. These features are :

- Pain

- Deformity

- Oedema

- Loss of Function

- Muscle Spasm

- Muscle Atrophy

- Abnormal Movement

- Limitation in Joint Range of Motion

- Shock

When Is Fracture Healed[edit | edit source]

The average time for bone healing is about 6-8 weeks, but can varies depending upon many factors;

Local Factors

- The type of fracture, severity and extent of the misalignment of the fractured bone.

- Infections that can lead to delayed, poor, or non-union healing.

- The blood supply to the fractured bone.

- The type of fixation (cast, splint, ORIF procedure, etc).

Systemic Factors

- The age of the person (individuals with osteoporosis are predisposed to further healing complications).

- The nutritional status of the individual.

- Smoking (delayed healing)

- The treatment undergone.[11]

A fracture is considered to be clinically healed based upon the combination of physical findings and symptoms over time. The following suggest complete healing :

- Absence of pain on weight-bearing, lifting or movement

- No tenderness on palpation at the fracture site

- Blurring or disappearance of the fracture line on X-ray

- Full or near to full functional ability[12].

Treatment and Prognosis[edit | edit source]

The basics of fracture healing rely on alignment and immobilisation.

Alignment may or may not be necessary depending on the degree of displacement, the importance of correct alignment (e.g. index finger vs rib), and the patient (e.g. professional athlete vs debilitated elderly).

Immobilisation can be achieved in a variety of ways, depending on the location, morphology of the fracture, and device of fixation

- None (e.g. most rib fractures)

- Sling (e.g. many clavicular fractures)

- Cast (e.g. many forearm fractures)

- Internal fixation (e.g. most hip fractures)

- External fixation

Fixation Devices[edit | edit source]

Stress Sharing Devices[edit | edit source]

It allows micromotion between the two fractured sites and partial transmission of load. This promotes secondary bone healing with callus formation (a relatively rapid bone healing).

For example; intramedullary nail, casts, and rods.

Stress Shielding Devices[edit | edit source]

The stress at the fracture site is transmitted through the shielding device therefore, there is no motion at the fracture site. This promotes primary bone healing without callus formation (slower than the healing with callus formation).

For example; compression plate[14][15].

Role of Physiotherapy[edit | edit source]

The physiotherapist’s role is to identify the root cause of the problem and select appropriate treatment techniques to help patients return to their desired activities of daily living.

As with any physiotherapy session, conducting a patient assessment is crucial. The problem-oriented medical record (POMR) system is based on a data collection system that incorporates the acronym SOAP:

- Subjective – information given by the patient: allergies, past medical history, past surgical history, family history, social history (living arrangements, social conditions, employment, medication), review of systems.

- Objective – all information obtained through observation or testing, e.g. range of joint movement, muscle strength.

- Analysis – a listing of problems based on what you know from a review of subjective and objective data.

- Plan – this refers to the plan of treatment).

The treatment provided is largely dependent on the problems identified during your initial assessment. may include a mixture of the following:

Examples of early treatment include;

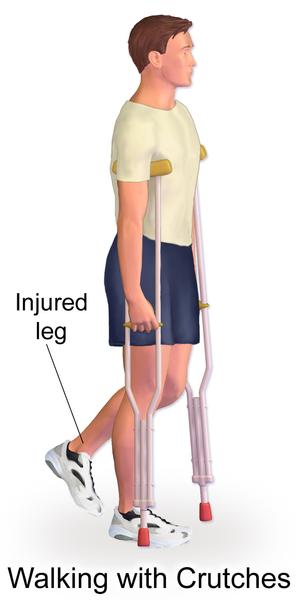

- Education

- on ambulation with assistive devices during various tasks such as walking up and down stairs or getting in and out of a car. Consideration of the client's weight-bearing restrictions is also crucial during these sessions, advising clients on ways to ambulate whilst adhering to the restrictions. Since safety is paramount, it's essential that clients are proficient and comfortable using these devices prior to discharge.

- on the application and removal of slings post upper extremity fractures.

- Soft tissue massage, particularly to manage oedema and swelling

- Scar management post-surgery

- Ice therapy

- Stretching exercises to regain joint range of movement

- Joint manual therapy and mobilizations to assist in regaining joint mobility

- Structured and progressive strengthening regime

- Balance and control work and gait (walking) re-education where appropriate

- Taping to support the injured area/help with swelling management

- Return to sport preparatory work and advice where required[12]

References[edit | edit source]

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 Radiopedia Fracture Available from:https://radiopaedia.org/articles/fracture-1 (last accessed 2.4.2020)

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 2.4 2.5 Bigham‐Sadegh A, Oryan A. Basic concepts regarding fracture healing and the current options and future directions in managing bone fractures. International wound journal. 2015 Jun;12(3):238-47.

- ↑ Radiology Key. Types of Fractures in Children. Available from:https://radiologykey.com/types-of-fractures-in-children/ (last accessed 10.18.2022)

- ↑ Bahney CS, Zondervan RL, Allison P, Theologis A, Ashley JW, Ahn J, Miclau T, Marcucio RS, Hankenson KD. Cellular biology of fracture healing. Journal of Orthopaedic Research®. 2019 Jan;37(1):35-50.

- ↑ Kostenuik P, Mirza FM. Fracture healing physiology and the quest for therapies for delayed healing and nonunion. Journal of Orthopaedic Research®. 2017 Feb;35(2):213-23.

- ↑ Whats Up Dude. How Does A Bone Break Heal - Bone Fracture Healing Process. Available from: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=od8oU5OLMGU[last accessed 8/6/2020]

- ↑ Maitre S. Causes, clinical manifestations, and treatment of fat embolism. AMA Journal of Ethics. 2006 Sep 1;8(9):590-2.

- ↑ Hershey K. Fracture complications. Critical Care Nursing Clinics. 2013 Jun 1;25(2):321-31.

- ↑ Jackson LC, Pacchiana PD. Common complications of fracture repair. Clinical techniques in small animal practice. 2004 Aug 1;19(3):168-79.

- ↑ Jay Cheon. Complications of fractures. Available from: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=RKScXgsYXwk[last accessed 8/6/2020]

- ↑ Sheen JR, Garla VV. Fracture Healing Overview. InStatPearls [Internet] 2019 Nov 25. StatPearls Publishing.

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 Tidy's Physiotherapy Chapter 22 Churchill Livingstone Elsevier London 2013

- ↑ ORTHOfilms. Principles of Fracture Healing. Available from: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=VZF3xicLtTw[last accessed 10/18/2022]

- ↑ Burgoyne W. Treatment and rehabilitation of fractures. Edited by Stanley Hoppenfeld and Vasantha L. Murthy. Pp 574. Hagerstown, Maryland: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 2000. ISBN: 0-7817-2197-0. $69.95.

- ↑ Orthopedic chirugus, Biomechanical principles of fracture fixation[Internet]. 2018 [cited 18 October 2022]. Available from:http://chambalravine.blogspot.com/2013/07/biomechanical-principles-of-fracture.html