Restrictive Lung Disease

This article or area is currently under construction and may only be partially complete. Please come back soon to see the finished work! (9/05/2021)

Original Editor - Lucinda hampton

Top Contributors - Lucinda hampton, Kim Jackson and Vidya Acharya

Introduction[edit | edit source]

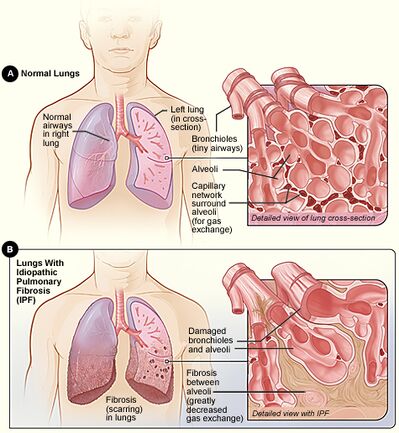

Restrictive lung diseases are a heterogeneous set of pulmonary disorders defined by restrictive patterns on spirometry. These disorders are characterized by a reduced distensibility of the lungs, compromising lung expansion, and, in turn, reduced lung volumes, particularly with reduced total lung capacity (TLC).[1]

Etiology[edit | edit source]

Its aetiology can be highly variable ranging from

- Intrinsic - with lung parenchymal involvement ie Interstitial Lung Disease (ILD): an umbrella term that encompasses a large number of disorders that are characterised by diffuse cellular infiltrates in a periacinar location. The spectrum of conditions included is broad, ranging from occasional self-limited inflammatory processes to severe debilitating pulmonary fibrosis[2].

- Extrinsic to the lung -

- obesity

- neuromuscular disorders

- chest wall deformities

Those with a restrictive lung disease pattern can often have decreased lung volumes, an increased work of breathing, and inadequate ventilation and/or oxygenation. Pulmonary function tests often demonstrate a decrease in the forced vital capacity (FVC)[3].

Examples of ILD[edit | edit source]

Intrinsic restriction can be caused by intrapulmonary restriction due to inflammatory processes within the lung tissue by diseases categorized under ILD

- Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF)

- Inorganic dust exposure such as silicosis, asbestosis, talc, pneumoconiosis, berylliosis, hard metal fibrosis, coal worker's pneumoconiosis, chemical worker's lung

- Organic dust exposure such as Aspergillosis, bird fancier's lung, bagassosis, and mushroom worker's lung, neonatal respiratory distress syndrome, hot tub pneumonitis

- Non-specific interstitial pneumonia (NSIP)

- Medications such as nitrofurantoin, amiodarone, gold, phenytoin, thiazides, hydralazine, bleomycin, carmustine, cyclophosphamide, methotrexate

- Sarcoidosis

- Radiation Therapy

- Acute interstitial pneumonia (AIP)[1]

Epidemiology[edit | edit source]

The overall prevalence of restrictive diseases is difficult to estimate precisely because the groups involve multiple pathological conditions, each of which can occur in numerous clinical stages.

The populations with higher associations to restrictive lung patterns include:

- Older Persons- The prevalence of restrictive conditions increases from 2.7 cases per 100,000 persons in individuals aged 35-44 years to over 175 cases per 100,000 in those older than 75 years.

- African Americans- Compared to Whites (10.9 cases per 100,000), the prevalence in this group is 35.5 cases per 100,000 persons.

- Obese individuals- Restrictive patterns are related to an elevated body mass index (BMI) with a decrease in lung volumes attributed to an increased amount of central obesity.

- Smokers.[1]

Diagnosis[edit | edit source]

Diagnostic testing for lung disease may include any of the following:

- Pulmonary function tests

- Chest X-ray

- CT scans

- Bronchoscopy

- Pulse oximetry[4]

Treatment[edit | edit source]

Treatment of lung disease depends on many factors, such as the type and stage of disease, family history, patient’s medical history and the health and age of the patient. Any of the following may be used for treating lung disease:

- Inhalers

- Expectorants

- Antibiotics

- Oxygen therapy

- Chemotherapy

- Lung transplantation[4]

- Impairment in pulmonary function in patients with severe scoliosis may be controlled with surgical correction.

- For obese patients, management involves losing weight by a combination of diet and physical exercise. Morbidly obese patients who fail to lose weight by traditional methods should be referred for gastric bypass surgery evaluation.[1]

Physiotherapy[edit | edit source]

SeePulmonary Rehabilitationand Role of Pulmonary Rehabilitation in Silicosis

Also Individual Links above

End of Life Care[edit | edit source]

Despite increasing mortality due to interstitial lung disease (ILD) the provision of end-of-life care for these conditions is limited. Improving quality of care for patients with advanced ILD or any other progressive respiratory disease requires a paradigm shift. Best supportive care as it is currently experienced is far from best. Palliative care needs to sit alongside curative intent as an equally legitimate professional goal.[5]

References[edit | edit source]

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 Martinez-Pitre PJ, Sabbula BR, Cascella M. Restrictive Lung Disease. StatPearls [Internet]. 2020 Jul 15.Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK560880/ (accessed 9.5.2021)

- ↑ Radiopedia Interstitial Lung Disease Available from:https://radiopaedia.org/articles/interstitial-lung-disease?lang=gb (accessed 9.5.2021)

- ↑ Radiopedia Restrictive Lung Disease Available from:https://radiopaedia.org/articles/restrictive-lung-disease (accessed 9.5.2021)

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 John Hopkins Restrictive Lung Disease Available from:https://www.hopkinsmedicine.org/health/conditions-and-diseases/restrictive-lung-disease (accessed 9.5.2021)

- ↑ Taylor DR. Progressive respiratory disease: the importance of prognostic conversations and advance care planning. Breathe. 2017 Dec 1;13(4):269-73.Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5709798/ (accessed 9.5.2021)