Systemic Lupus Erythematosus

Original Editors - Alli Christian from Bellarmine University's Pathophysiology of Complex Patient Problems project. Top Contributors - Alli Christian, Elaine Lonnemann, Admin, Lucinda hampton, Kim Jackson, Rachael Lowe, Lotte Vonck, Khloud Shreif, 127.0.0.1, Laura Ritchie, Wendy Walker and WikiSysop - Elaine Lonnemann

Definition/Description[edit | edit source]

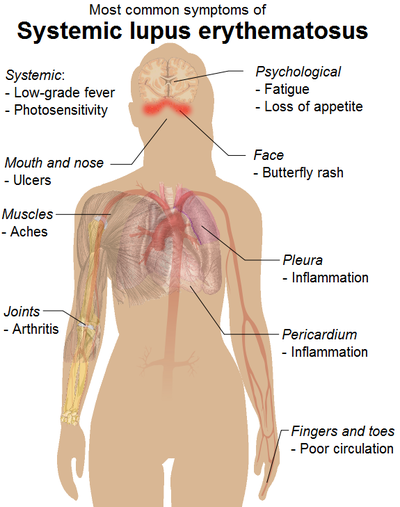

Systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) is a chronic autoimmune disease characterized by an inflammation of connective tissue disease with variable manifestations.

- SLE may affect many organ systems with immune complexes and a large array of autoantibodies, particularly antinuclear antibodies (ANAs).

- Although abnormalities in almost every aspect of the immune system have been found, the key defect is thought to result from a loss of self-tolerance to autoantigens.[1]

- It is a disease characterized by relapses, flares, and remissions.

- Common manifestations, in addition to the malar rash, include cutaneous photosensitivity, nephropathy, serositis, and polyarthritis.

- The overall outcome of the disease is highly variable with extremes ranging from permanent remission to death[1].

Epidemiology[edit | edit source]

- There is a strong female predilection in adults, with women affected 9-13 times more than males. In children, this ratio is reversed, and males are affected two to three times more often.

- Can affect any age group - the peak age at onset is around the 2nd to 4th decades, with 65% of patients presenting between the ages of 16 and 65 years (i.e. during childbearing years).

- Disease is more common in childbearing age in women however it has been well reported in the pediatric and elderly population. SLE is more severe in children while in the elderly, it tends to be more insidious onset and has more pulmonary involvement and serositis and less Raynaud's, malar rash, nephritis, and neuropsychiatric complications[2]

- Studies have indicated that although rare, lupus in men tends to be more severe.

- Prevalence varies according to ethnicity with ratios as high as 1:500 to 1:1000 in Afro-Caribbeans and indigenous Australians, down to 1:2000 in Caucasians.[1]

Etiology[edit | edit source]

The cause of lupus erythematosus is not known.

- A familial association has been noted that suggests a genetic predisposition, but a genetic link has not been identified. Approximately 8% of patients with SLE have at least one first-degree family member (parent, sibling, child) with the disease.

- Environmental factors - Ultraviolet light (increased keratinocyte apoptosis), infection (via molecular mimicry and bacterial CpG motifs), smoking (odds ratio (OR): 1.56 in current smokers, 1.23 in ex-smokers), environmental pollutants (silica) and intestinal dysbiosis (ie digestive disturbances, frequent gas or bloating, feel bloated on most days of the week, abdominal cramping, diarrhea, and constipation) are all known risk factors for SLE.

- Hormonal abnormality and ultraviolet radiation are considered possible risk factors for the development of SLE[1].

- Some drugs have been implicated as initiating the onset of lupus-like symptoms and aggravating existing disease; they include hydralazine hydrochloride, procainamide hydrochloride, penicillin, isonicotinic acid hydrazide, chlorpromazine, phenytoin, and quinidine.

- Possible childhood risk factors include low birth weight, preterm birth, and exposure to farming pesticides[3].

Pathological Process[edit | edit source]

SLE can affect multiple components of the immune system, including the

- Complement system (i.e. a part of the immune system that enhances the ability of antibodies and phagocytic cells to clear microbes and damaged cells from an organism, promote inflammation, and attack the pathogen's cell membrane),

- T-suppressor cells: in SLE T cells are key players in causing inflammation and autoimmunity. They release pro-inflammatory cytokines, stimulate B cells to produce harmful autoantibodies and maintain the disease through autoreactive memory T cells. However, SLE patients exhibit abnormal T-cell ratios and functions. T follicular helper (Tfh) cells, essential for immune responses, expand excessively in SLE due to interactions with antigen-presenting cells and TLR7 activation. This leads to heightened antibody production and immune tolerance breakdown. Conversely, regulatory T (Treg) [4]cells, responsible for immune control, are impaired in SLE, partly due to reduced IL-2 levels caused by low activator protein 1 (AP-1) expression. IL-2 also helps restrain the pro-inflammatory cytokine IL-17, elevated in SLE, contributing to tissue damage. Overall, T cell dysregulation is a central feature in SLE pathogenesis[5].

- Cytokine production.

Emerging evidence has demonstrated a key player in the generation of autoantigens in SLE is the increase in generation (i.e. increased apoptosis) and/or decrease in clearance of apoptotic cell materials (i.e., decreased phagocytosis).

Results in the generation of autoantibodies, which may circulate for many years prior to the development of overt clinical SLE. The disease tends to have a relapsing and remitting course.[1]

Clinical Presentation[edit | edit source]

SLE has a myriad of clinical features:

- CNS manifestations of systemic lupus erythematosus (CNS lupus): neuropsychiatric events can occur in ~45% (range 14-75%) of cases

- Gastrointestinal manifestations of systemic lupus erythematosus: there may be GI involvement in ~20% of cases (Ascites, peritonitis, oral ulcers, esophageal dysmotility, and protein-losing enteropathy)

- Musculoskeletal manifestations of systemic lupus erythematosus (Jaccoud's arthropathy, arthralgia, arthritis, synovitis, tenosynovitis, and myositis)

- Renal manifestations of systemic lupus erythematosus ( Proteinuria, hematuria, and glomerulonephritis).

- Cardiovascular manifestation (Libman-sacks-endocarditis, pericarditis, myocarditis).

- Thoracic manifestations of systemic lupus erythematosus (Pleuritis, pulmonary arterial HTN, interstitial lung disease, pleural effusion).[1][6]

SLE can affect many organs of the body, but it rarely affects them all. The following list includes common signs and symptoms of SLE in order of the most to least prevalent.

All of the below symptoms might not be present at the initial diagnosis of SLE, but as the disease progresses more of a person’s organ systems become involved.[7]

The most common symptoms associated with SLE are:

- Constitutional symptoms (fever, malaise, fatigue, weight loss): most commonly fatigue and a low-grade fever.

- Achy joints (arthralgia)

- Arthritis (inflamed joints)

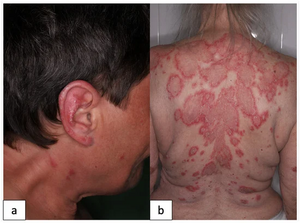

- Skin rashes; top facial rash, and bottom discoid rash

- Pulmonary involvement (symptoms include: chest pain, difficulty breathing, and cough)

- Anemia

- Kidney involvement (lupus nephritis)

- Sensitivity to the sun or light (photosensitivity)

- Hair loss

- Raynaud’s phenomenon

- CNS involvement (seizures, headaches, peripheral neuropathy, cranial neuropathy, cerebrovascular accidents, neurocognitive disorder, psychosis)

- Mouth, nose, or vaginal ulcers[6]

- The most common signs and symptoms of SLE in children and adolescents are fever, fatigue, weight loss, arthritis, rash, and renal disease.[8]

Systemic Involvement[edit | edit source]

There are many visceral systems that can be affected by SLE, but the extent of the body's involvement differs from person to person. Some people diagnosed with SLE have only a few visceral systems involved, while others have numerous systems that have been affected by the disease.

Musculoskeletal System[edit | edit source]

- Arthritis- typically affects hand, wrists, and knees

- Arthralgia

- Tenosynovitis

- Tendon ruptures

- Swan-neck deformity

- Ulnar drift

Cardiopulmonary/Cardiovascular System[edit | edit source]

- Pleuritis

- Pericarditis

- Dyspnea

- Hypertension

- Myocarditis

- Endocarditis

- Tachycarditis

- Pneumonitis

- Vasculitis

Central Nervous System[edit | edit source]

- Emotional instability

- Psychosis

- Seizures

- Cerebrovascular accidents

- Cranial neuropathy

- Peripheral neuropathy

- Organic brain syndrome

Renal System[edit | edit source]

- Glomerulonephritis -an inflammatory disease of the kidneys

- Hematuria

- Proteinuria

- Kidney failure[6]

Cutaneous System[edit | edit source]

- Calcinosis

- Cutaneous vasculitis

- Hair loss

- Raynaud's phenomenon

- Mucosal ulcers

- Petechiae

Blood Disorders[edit | edit source]

- Anemia

- Thrombocytopenia

- Leukopenia

- Neutropenia

- Thrombosis

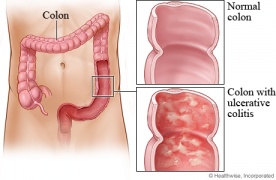

Gastrointestinal System[edit | edit source]

- Ulcers--Throat & Mouth

- Ulcerative colitis/Crohn's disease

- Peritonitis

- Ascites

- Pancreatitis

- Peptic ulcers

- Autoimmune Hepatitis [9]

Associated Co-morbidities[edit | edit source]

Include:

- Fibromyalgia.[10]

- Atherosclerosis[11] [12]

- Lupus Nephritis- leads to End Stage Renal Disease (ESRD)

- Anemia[13]

- Some types of cancers (especially non-Hodgkin's lymphoma and lung cancer) [12][14] [15]

- Infections

- Hypertension

- Dyslipidemia

- Diabetes Mellitus

- Osteoporosis

- Avascular Necrosis [12]

Diagnosis[edit | edit source]

The diagnosis of SLE may be made if four of eleven ACR (American College of Rheumatology) criteria are present, either serially or simultaneously 2. These criteria were initially published in 1982 but were revised in 1997.

ACR criteria:[3]<section><section>

| Criteria | Explanation |

| Serositis | Pericarditis, pleurisy on electrocardiogram or imaging scan |

| Oral ulcers | Sores, usually painless, on the lips and in the mouth |

| Arthritis | Tenderness or swelling of two or more peripheral joints |

| Photosensitivity | Unusual skin reaction (skin rash) to sun exposure |

| Blood disorder | Leukopenia, lymphopenia, thrombocytopenia, hemolytic anemia |

| Renal involvement | Proteinuria, cellular casts |

| Antinuclear antibodies | Elevated titers |

| Immune phenomenon | Presence of antibodies or lupus erythematosus cells |

| Neurological disorder | Seizures or psychosis in absence of other causes |

| Malar rash | Fixed erythema over cheeks and nose |

| Discoid rash | Raised, red lesions with scaling and follicular plugging |

</section></section>

Medical Management[edit | edit source]

The goal of treatment in SLE is to prevent organ damage and achieve remission. The choice of treatment is dictated by the organ system/systems involved and the severity of involvement and ranges from minimal treatment (NSAIDs, antimalarials) to intensive treatment (cytotoxic drugs, corticosteroids).

- Patient education, physical and lifestyle measures, and emotional support play a central role in the management of SLE.

- Patients with SLE should be well educated on the disease pathology, potential organ involvement including brochures, and the importance of medication and monitoring compliance.

- Stress reduction techniques, good sleep hygiene, exercises, and use of emotional support shall be encouraged.

- Smoking can worsen SLE symptoms - educated about the importance of smoking cessation.

- Dietary recommendations - avoiding alfalfa sprouts and echinacea and including a diet rich in vitamin-D.

- Photoprotection is vital, and all patients with SLE shall avoid direct sun exposure by timing their activities appropriately, light-weight loose-fitting dark clothing covering the maximum portion of the body, and using broad-spectrum (UV-A and UV-B) sunscreens with sun protection factor (SPF) of 30 or more (see image R)

Physical Therapy Management[edit | edit source]

Exercise is beneficial for patients with SLE because it decreases their muscle weakness; while simultaneously; increasing their muscle endurance. Physical therapists can play an important role for patients with SLE during and between exacerbations. The patient's need for physical therapy will vary greatly depending on the systems involved.

- Education: It is essential for patients with skin lesions to have appropriate education on the best way to care for their skin and to ensure they do not experience additional skin breakdown.

- Aerobic Exercise: One of the most common impairments that patients with SLE experience is generalized fatigue that can limit their activities throughout the day.[6] Graded aerobic exercise programs are more successful than relaxation techniques in decreasing the fatigue levels of patients with SLE. Aerobic activity causes many with SLE to feel much better. The aerobic exercise program may consist of 30-50 minutes of aerobic activity (walking/swimming/cycling) with a heart rate corresponding to 60% of the patient's peak oxygen consumption.[16] Both aerobic exercise and range of motion/muscle strengthening exercises can increase the energy level, cardiovascular fitness, functional status, and muscle strength in patients with SLE (aerobic exercise for 20-30 minutes at 70-80% of their maximum heart rate,3 times a week for 50 minutes sessions).[17]

- Energy Conservation: Physical therapists; can educate patients on appropriate; energy conservation techniques and the best ways to protect joints that; are susceptible to damage.

- Additionally, physical therapists and patients with SLE should be aware of signs and symptoms that suggest a progression of SLE including those associated with avascular necrosis, kidney involvement, and neurological involvement.[6]

Occupational Therapy Management[edit | edit source]

During evaluation occupational therapists (OTs) use activity analysis to break down these activities into parts to detect where patient's challenges exist, such as issues with mobility, strength, sensation, pain, or endurance. This assessment helps OTs recommend solutions like splints, home modifications, or post-surgery support and introduce effective adaptations and techniques to enhance independence in daily life[18].

- Self-management strategies: involves teaching the patient how to identify and avoid potential triggers for flares, in addition, to recognizing early warning signs, and embracing a healthy lifestyle. This includes adhering to routine medical check-ups, prioritizing rest, minimizing stress, sun protection, maintaining a nutritious diet, regular exercise, and consistent medication adherence, all of which collectively contribute to reducing the likelihood of lupus flares and promoting overall well-being.

- Education: OTs help to safeguard their joints, reduce tiredness, and minimize pain, individuals with lupus can simplify their daily routines, take things slowly when performing tasks, and think ahead to plan their activities which in turn enhances their ability to perform daily tasks like self-care, work, and leisure activities.

- Adaptive strategies: OTs can teach them self-management skills to handle daily tasks, and adaptive strategies to help them engage in desired activities.

- Environmental modifications: OTs help to identify the physical barriers that are limiting the client from engaging in their desired daily activities also suggest the use of adaptive equipment and modifications in the environment, such as easy-to-grip handles and raised toilet seats, to conserve energy and protect joints.

These combined strategies aim to meet patients' functional needs and support their independence in various activities despite limitations in joint motion, strength, and endurance.

Prognosis[edit | edit source]

Recent advances in diagnosis and treatment strategies have resulted in a survival improvement from a 5-year survival at 40-50% in the 1950s up to a 10-year survival now estimated at 80-90%. Nevertheless, patients with SLE have a standardised mortality ratio of 3.

Early deaths in the disease course are usually due to active disease and immunosuppression while late deaths tend to arise from coronary artery disease and SLE or treatment complications (e.g. end-stage kidney disease from lupus nephritis).[1]

Resources[edit | edit source]

Occupational Therapy and Health Promotion with Lupus

References[edit | edit source]

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 1.5 1.6 Ameer MA, Chaudhry H, Mushtaq J, Khan OS, Babar M, Hashim T, Zeb S, Tariq MA, Patlolla SR, Ali J, Hashim SN. An overview of systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) pathogenesis, classification, and management. Cureus. 2022 Oct 15;14(10).

- ↑ Tsai HL, Chang JW, Lu JH, Liu CS. Epidemiology and risk factors associated with avascular necrosis in patients with autoimmune diseases: a nationwide study. Korean J Intern Med. 2022 Jul;37(4):864-876.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 Nursing central SLE Available from:https://nursing.unboundmedicine.com/nursingcentral/view/Diseases-and-Disorders/73651/all/Lupus_Erythematosus (last accessed 5.6.2020)

- ↑ Giang S, La Cava A. Regulatory T cells in SLE: biology and use in treatment. Current rheumatology reports. 2016 Nov;18:1-9.

- ↑ Clinical relevance of T follicular helper cells in systemic lupus erythematosus. Nakayamada S, Tanaka Y. Expert Rev Clin Immunol. 2021;17:1143–1150

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 6.3 6.4 Goodman CC, Fuller KS. Pathology: Implications for the Physical Therapist. 3rd edition. St. Louis, Missouri: Saunders Elsevier, 2009.

- ↑ Cojocaru M, Cojocaru IM, Silosi I, Vrabie CD. Manifestations of systemic lupus erythematosus. Maedica. 2011 Oct;6(4):330.

- ↑ Tucker LB. Making the diagnosis of systemic lupus erythematosus in children and adolescents. Lupus. 2007 Aug;16(8):546-9.

- ↑ Lupus Foundation of America. How lupus affects the body page. Website updated: 2010. Website accessed: February 17, 2010.

- ↑ Goodman CC, Snyder TE. Differential diagnosis for physical therapists screening for referral, Saunders Elsevier, St. Louis, MO. 2007:274-364.

- ↑ Becker-Merok A, Nossent JC. Prevalence, predictors and outcome of vascular damage in systemic lupus erythematosus. Lupus. 2009 May;18(6):508-15.

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 12.2 Bertsias G, Gordon C, Boumpas DT. Clinical trials in systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE): lessons from the past as we proceed to the future–the EULAR recommendations for the management of SLE and the use of end-points in clinical trials. Lupus. 2008 May;17(5):437-42.

- ↑ Wingard R. Increased risk of anemia in dialysis patients with comorbid diseases. Nephrology Nursing Journal. 2004 Mar 1;31(2):211.

- ↑ Medical Foundation for Medical Education and Research. Mayo Clinic: Lupus Page. www.mayoclinic.com. Updated October 20, 2009. Accessed February 17, 2010.

- ↑ Bernatsky S, Boivin JF, Joseph L, Rajan R, Zoma A, Manzi S, Ginzler E, Urowitz M, Gladman D, Fortin PR, Petri M. An international cohort study of cancer in systemic lupus erythematosus. Arthritis & Rheumatism. 2005 May;52(5):1481-90.

- ↑ Tench CM, McCarthy J, McCurdie I, White PD, D'Cruz DP. Fatigue in systemic lupus erythematosus: a randomized controlled trial of exercise. Rheumatology. 2003 Sep 1;42(9):1050-4.

- ↑ Ramsey‐Goldman R, Schilling EM, Dunlop D, Langman C, Greenland P, Thomas RJ, Chang RW. A pilot study on the effects of exercise in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus. Arthritis Care & Research. 2000 Oct;13(5):262-9.

- ↑ Baker NA, Carandang K, Dodge C, Poole JL. Occupational Therapy Is a Vital Member of the Interprofessional Team-Based Approach for the Management of Rheumatoid Arthritis: Applying the 2022 American College of Rheumatology Guideline for Exercise, Rehabilitation, Diet, and Additional Integrative Interventions for Rheumatoid Arthritis. Arthritis care & research. 2023 May 25.

- ↑ Lupus LA. The Benefits of Occupational Therapy in Lupus. Available from: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=r7aXjoMKBPg [last accessed 28/9/2023]