Sport Injury Classification

Original Editor - Naomi O'Reilly Top Contributors - Naomi O'Reilly, Wanda van Niekerk, Vidya Acharya, Kim Jackson, Claire Knott, Jess Bell, 127.0.0.1, Tony Lowe, WikiSysop, Samuel Adedigba, Khloud Shreif and Aminat Abolade

Introduction[edit | edit source]

Sports injuries are diverse in terms of the mechanism of injury, how they present in individuals, and how the injury should be managed. Defining exactly what a sports injury is can be problematic and definitions are not consistent. Verhagen et al. (2010) highlighted that definitions of sports injury can be discussed in both theoretical and operational terms.[1]

According to the IOC manual of sports injuries (2012)[2] a sports injury may be defined as "damage to the tissues of the body that occurs as a result of sport or exercise." [2]

The International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health (ICF) is one of the most well know mechanisms and considered to be the gold standard for classification of medical conditions but is currently rarely used in the field of sports medicine. For researchers in sport defining simple, pragmatic, consistent, operational criteria which describe an injury that can be applied across a range of sports is vital, particularly when developing injury surveillance systems. Many comprehensive systems have been developed to classify injury in order to assist with the development of injury surveillance which can be used across sports.[1] There are many ways to classify sports injuries based on:

- the time taken for the tissues to become injured

- tissue type affected

- the severity of the injury, and

- which injury the individual presents with.

Injury Classification[edit | edit source]

Classification of sporting injuries (adapted from Brukner and Khan's Clinical Sports Medicine[3])[edit | edit source]

| Site | Acute Injuries | Overuse Injuries |

|---|---|---|

| Bone | Fracture

Periosteal contusion |

Stress fracture

Bone strain Stress reaction Osteitis Periostitis Apophysitis |

| Articular cartilage | Osteochondral/chondral fracture

Minor osteochondral injury/lesion |

Chondropathy (e.g. chondromalacia) |

| Joint | Dislocation

Subluxation |

Synovitis

Osteoarthritis |

| Ligament | Sprain/tear (grades I - III) | Inflammation |

| Muscle | Strain/tear (grades I - III)

Contusion Cramp Compartment syndrome (acute) |

Compartment syndrome (chronic)

Delayed onset muscle soreness (DOMS) Focal tissue thickening/fibrosis |

| Tendon | Tear (complete or partial) | Tendinopathy |

| Bursa | Traumatic bursitis | Bursitis |

| Nerve | Neuropraxia | Nerve entrapment

Minor nerve injury/irritation Adverse neural tension |

| Skin | Laceration

Abrasion Puncture wound |

Blister

Callus |

Mechanism[edit | edit source]

According to Brukner & Kahn (2012)[3] this is one of the most common methods of classifying sports injuries and relies on the sports physiotherapist knowing and understanding both the mechanism of injury and the onset of the symptoms.

Acute Injuries[edit | edit source]

An injury occurs suddenly to previously normal tissue. Acute injuries occur due to sudden trauma to the tissue, with the symptoms of acute injuries presenting themselves almost immediately. The principle in this instance is that the force exerted at the time of injury on the tissue (i.e. muscle, tendon, ligament, and bone) exceeds the strength of that tissue. Forces commonly involved in acute injury are either direct or indirect. Acute injuries can be classified according to the site of the injury (e.g. bone, cartilage, ligament, muscle, bursa, tendon, joint, nerve or skin) and the type of injury (e.g. fracture, dislocation, sprain or strain).[3]

Direct/Contact Injury[edit | edit source]

A direct injury is caused by an external blow or force (extrinsic causes)

- A collision with another person e.g, during a tackle in rugby or football

- Being struck by an object e.g. a basketball or hockey stick

Indirect/Non-Contact Injury[edit | edit source]

An indirect injury can occur in two ways (intrinsic causes):

- The actual injury can occur some distance from the impact site e.g. falling on an outstretched hand can result in a dislocated shoulder

- The injury does not result from physical contact with an object or person, but from internal forces built up by the actions of the performer, such as injuries that may be caused by over-stretching, poor technique, fatigue, and lack of fitness. (e.g. muscle strain or ligament sprain)

Common Acute Injuries include:[edit | edit source]

Overuse Injuries[edit | edit source]

Any repetitive activity can lead to an overuse injury. Overuse injuries occur over a period of time, usually due to excessive and repetitive loading of the tissue, with symptoms presenting gradually. Little or no pain might be experienced in the early stages of these injuries and the athlete might continue to place pressure on the injured site. This prevents the site from being given the necessary time to heal. In contrast to acute injuries, the cause of overuse injuries is often much less obvious. The principle in overuse injury is that repetitive microtrauma overloads the capacity of the tissue to repair itself.[4]

To better understand overuse injury it helps to think in terms of what is happening at the microscopic level to the tissue that has been “stressed” during the repetitive workouts. During exercise, the tissues (muscles, tendons, bones, ligaments, etc) experience excessive physiological stress. When the activity is over, the tissues undergo adaptation so as to be stronger to be able to withstand similar stress in the future, if required. Overuse injury occurs when the adaptive capability of the tissue is exceeded and tissue injury then develops.[4] That is, in the over-zealous athlete there is not enough time for adaptation to occur before the next work out and the cumulative tissue damage eventually exceeds a threshold for that tissue causing pain and tissue dysfunction. The adaptive capability of the tissue may be exceeded secondary to excessive repetitive forces attributable to one or more commonly a combination of risk factors including:[4]

| Intrinsic[3][4] | Extrinsic[3][4] |

|---|---|

Age

Physiology

Anatomical

Leg length discrepancy Other

|

Training Errors

Equipment

Environmental Conditions

Playing Surfaces

Psychological factors Inadequate Nutrition |

According to Clarsen (2015)[4] overuse injuries are a problem in many sports with athletes exposed to high training loads, tight competition schedules and insufficient recovery thought to be particularly at risk; especially when participating in sports involving repetitive movements or impacts. For example, approximately two-thirds of athletes, who trained between 20 and 35 hours per week, sustained a performance-limiting overuse injury in athletics over a one year period[5]. Similarly, between 29% and 44% of elite volleyball players, who often perform over 500 jumps per week[6], report symptoms of jumper’s knee[7][8]. Achilles Tendinopathy is a common overuse injury in football, as the sport involves running and jumping activities. In the English football league, there is an average of 3.5 Achilles tendon-related injuries per week during the preseason and an average of one injury per week during the competition season.[9] While it is recognised that overuse injuries are common in elite sports, they also occur among recreational athletes[10], young athletes[11], and even among sedentary individuals after transient increases in activity levels.[12]

Common types of overuse injuries in sports (adapted from Brukner and Khan's Clinical Sports Medicine[3]):[edit | edit source]

| Site | Type of overuse injury | Common examples in Sport |

|---|---|---|

| Bone | Bone strain/stress reaction/stress fracture

Osteitis periostitis Apophysitis |

Metatarsal stress fracture in running, ballet

Medial tibial stress syndrome in running and dancing Osgood Schlatter lesion Lumbar stress fracture in gymnastics, cricket fast bowling Pubic ramus in distance running |

| Tendon | Tendinopathy (includes paratenonitis, tenosynovitis, tendinosis and tendinitis | Achilles tendinopathy in footballers

Patellar tendinosis in volleyball ("jumper's knee") |

| Joint | Synovitis

Labrum injuries Chondropathy |

SLAP lesions in throwing athletes (e.g. baseball, cricket)

Functional acetabular impingement of the hip in football |

| Ligament | Chronic degeneration/micro-tears | Ulnar collateral ligament injury in baseball |

| Muscle/fascia | Chronic compartment syndrome

Delayed onset muscle soreness (DOMS) Fasciitis/Fasciosis |

Iliotibial band syndrome in running |

| Bursa | Bursitis | Greater trochanteric pain syndrome |

| Nerve | Altered neuromechanical sensitivity

Entrapment |

Ulnar neuropathy in cycling (Cyclist's palsy) |

Common overuse injuries[edit | edit source]

Tissue Type[edit | edit source]

Sports injuries can also be classified according to which tissue has damaged. This allows sports physiotherapists to identify soft, hard, and special tissue injuries. In more complex sports injuries damage may occur to more than one tissue type.

Soft Tissue Injuries[edit | edit source]

Ligament[edit | edit source]

Joint stability is provided by the presence of a joint capsule of connective tissue, thickened at points of stress to form ligaments, which attach at the ends to the bone. There are a number of different grading systems used for the classification of ligament sprains, each has its own strengths and weaknesses. One important consideration is that each therapist will employ different systems so it is important to be aware of a wide variety for continuity of care. This is evident when reading research regarding sprains and authors not disclosing which system they used, reducing rigour and quality of the write up of research[13]. Ligament injuries range from mild injuries, involving the tearing of only a few fibres to a complete tear of the ligament, which may lead to instability of the joint.[2][3]

The traditional grading system for ligament injuries focuses on a single ligament.[13]

Grade I Sprain[edit | edit source]

- Represents a microscopic injury without stretching of the ligament on a macroscopic level

- Some stretched fibres

- Clinical testing shows normal range of motion on stressing the ligament

- Mild - little swelling and tenderness with little impact on function

Grade II Sprain [edit | edit source]

- Macroscopic stretching, but the ligament remains intact.

- Involves a considerable proportion of the fibres and, therefore, stretching of the joint and stressing the ligament show increased laxity but a definite endpoint.

- Moderate - moderate swelling, pain and impact on function, reduced Proprioception, ROM (range of motion) and instability

Grade III Sprain[edit | edit source]

- Complete tear or rupture of the ligament with excessive joint laxity and no firm endpoint.

- Although they are often painful conditions, grade III sprains can also be pain-free as sensory fibres are completely torn in the injury.

- Severe - complete rupture, extensive swelling, tenderness, loss of function and marked instability

Common Ligament Injuries:[edit | edit source]

- MCL Injury Knee

- LCL Injury Knee

- ACL Injury Knee

- PCL Injury Knee

- Lateral Ligament Injury Ankle

- Elbow Ligamentous Injuries

Tendon[edit | edit source]

Tendons are situated between bone and muscles and are bright white in colour, their fibro-elastic composition gives them the strength required to transmit large mechanical forces. Normal tendons consist of tight parallel bundles of collagen fibres.[3] Each muscle has two tendons, one proximally and one distally. The point at which the tendon forms an attachment to the muscle is also known as the musculotendinous junction (MTJ) and the point at which it attaches to the bone is known as the osteotendinous junction (OTJ). The purpose of the tendon is to transmit forces generated from the muscle to the bone to elicit movement. The proximal attachment of the tendon is also known as the origin and the distal tendon is called the insertion[14].

Tendons have different shapes and sizes depending on the role of the muscle. Muscles that generate a lot of power and force tend to have shorter and wider tendons than those that perform more fine delicate movements. These tend to be long and thin.

Tendon rupture[edit | edit source]

Acute injuries to tendons usually occur at the point of least blood supply, for example with the Achilles tendon it is usually 2cm above the tendon insertion or at the musculotendinous junction. A complete tendon rupture generally occurs without warning. Also, this type of injury usually occurs in older athletes without a history of injury in that particular tendon. The most common tendons to rupture are the Achilles tendon and the Supraspinatus tendon.[3]

Tendinopathy[edit | edit source]

Tendinopathy refers to a chronic tendon injury with no implication about the aetiology (cause) and is the term that the leading researchers in the field of tendon science have been using in recent years. Overuse injuries are commonly seen in tendons. As a tendon is loaded and the strain increases, there is tissue deformation and some fibres begin to fail. Ultimately, macroscopic tendon failure occurs. Tendon overuse can not be explained as inflammation as research has shown that the histological findings in athletes with overuse tendon injuries do not show signs of inflammation - (there are no inflammatory cells present in surgical specimens). However, the following are seen with overuse tendon injuries:

- degenerative changes

- changed fibril organisation

- reduced cell count

- vascular in-growth

- occasionally, local necrosis.

Athletes with overuse tendon pain may present with the following clinical features:[2][3]

- pain some time after exercise or the following morning upon rising

- can be painful at rest and initially becomes less painful with use

- athletes can"run through the pain" or pain disappears when they warm-up

- pain returns after exercise when they cool down

- the athlete is able to train fully in the early stages of the condition - this may interfere with the healing process

- localised tenderness and thickening upon examination

- swelling and crepitus may be present (although crepitus is usually a sign of associated tenosynovitis or due to the water-attracting nature of the collage disarray)

Tendinitis[edit | edit source]

This refers to inflammation of the tendon itself. There is little evidence to support this diagnostic label, though. Tendinitis may occur in association with paratendinitis.[3]

Paratenonitis[edit | edit source]

This refers to inflammation of the paratenon, either aligned by the synovium or not.[2] This is likely to occur in areas where the tendon rubs over a bony prominence and the paratenon is directly irritated.[3] A common example is De Quervain's tenosynovitis at the wrist.

Read more on Tendon Anatomy, Tendon Pathophysiology, Tendon Biomechanics and Tendinopathy

Common Tendon Injuries:[edit | edit source]

Muscle[edit | edit source]

Skeletal muscle injuries represent a great part of all traumas in sports medicine, with an incidence from 10% to 55% of all sustained injuries. They should be treated with necessary precaution since a failed treatment can postpone an athlete’s return to the field with weeks or even months and cause re-occurrence of the injury. See our page on Muscle Injuries for more detailed information.

Common Injuries:[edit | edit source]

Skin[edit | edit source]

Skin injuries are common particularly in athletes playing contact sports. Underlying structures such as tendons, ligaments, blood vessels and nerves are always at risk of injury and should also be considered with any skin injury. Open wounds may include abrasions, lacerations, or puncture wounds.[3]

Hard Tissue Injuries[edit | edit source]

Articular Cartilage[edit | edit source]

The ends of long bones are lined with articular cartilage which provides a low friction gliding surface that acts as a shock absorber and reduces peak pressures on the underlying bone. These are common injuries and there is an increased risk of long term, premature osteoarthritis if not well managed. Articular cartilage can be damaged through shear injuries such as dislocations, and subluxation. Osteochondral injuries may be associated with soft tissue conditions such as injuries to ligaments e.g. ACL. There are three classes of articular cartilage injuries;

- Disruption of the deep layers with or without subchondral bone damage

- Disruption of the articular surface only

- Disruption of both the articular cartilage and subchondral bone

Bone[edit | edit source]

A bone is a rigid organ that constitutes part of the vertebral skeleton. Bones support and protect the various organs of the body, produce red and white blood cells, store minerals and also enable mobility as well as support for the body. Bone tissue is a type of dense connective tissue.

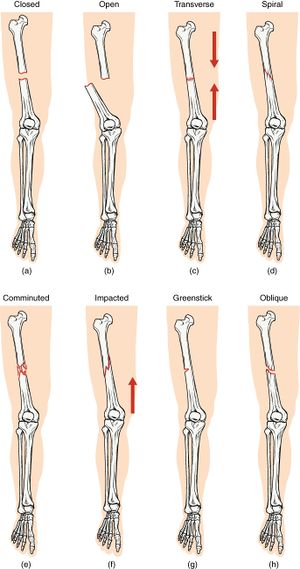

Fractures [edit | edit source]

A fracture can result from a direct force, an indirect force or repetitive smaller impacts (as occurs in a stress fracture) and can be classified as transverse, oblique, spiral or comminuted. Fracture complications include:[3]

- Infection

- Acute compartment syndrome

- Associated injury (e.g. nerve, vessel)

- Deep venous thrombosis/pulmonary embolism

- Delayed union/non-union and mal-union

The signs and symptoms of a fracture include:

- Pain and tenderness

- Swelling and discolouration

- Restriction of movement

- Unnatural movement

- Deformity

Joint [edit | edit source]

Dislocation [edit | edit source]

Dislocations are injuries to joints where one bone is displaced from another or a complete dissociation of the articulating surfaces of the joint. A dislocation is often accompanied by considerable damage to the surrounding connective tissue. Complications of dislocation can include nerve and vascular damage. Dislocations occur as a result of the joint being pushed past its normal range of movement. Common sites of the body where dislocations occur are the finger, shoulder and patella.[3]

Subluxation[edit | edit source]

Subluxation is an injury to the joint where one bone is partially displaced from another or partial dissociation of the articulating surfaces of the joint.

Signs and symptoms of dislocation and subluxation include:

- Loss of movement at the joint

- Obvious deformity

- Swelling and tenderness

- Pain

Resources[edit | edit source]

References [edit | edit source]

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Verhagen E, Van Mechelen W, editors. Sports injury research. Oxford University Press; 2010.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 2.4 Bahr R, Engebretsen L, Laprade R, McCrory P, Meeuwisse W, editors. The IOC manual of sports injuries: an illustrated guide to the management of injuries in physical activity. John Wiley & Sons; 2012 Jun 12.

- ↑ 3.00 3.01 3.02 3.03 3.04 3.05 3.06 3.07 3.08 3.09 3.10 3.11 3.12 3.13 3.14 Brukner P. Brukner & Khan's Clinical Sports Medicine. North Ryde: McGraw-Hill; 2012.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 4.4 4.5 Clarsen B. Overuse injuries in sport: development, validation and application of a new surveillance method.(dissertation). Oslo Sports Trauma Research Centre. Norwegian School of Sports Sciences. 2015.

- ↑ Jacobsson J, Timpka T, Kowalski J, Nilsson S, Ekberg J, Dahlström Ö, Renström PA. Injury patterns in Swedish elite athletics: annual incidence, injury types and risk factors. British Journal of Sports Medicine. 2013 Oct 1;47(15):941-52.

- ↑ Bahr MA, Bahr R. Jump frequency may contribute to risk of jumper's knee: a study of interindividual and sex differences in a total of 11 943 jumps video recorded during training and matches in young elite volleyball players. British journal of sports medicine. 2014 Sep 1;48(17):1322-6.

- ↑ Lian ØB, Engebretsen L, Bahr R. Prevalence of jumper's knee among elite athletes from different sports: a cross-sectional study. The American journal of sports medicine. 2005 Apr;33(4):561-7.

- ↑ Bahr R. No injuries, but plenty of pain? On the methodology for recording overuse symptoms in sports. British journal of sports medicine. 2009 Dec 1;43(13):966-72.

- ↑ Sobhani S, Dekker R, Postema K, Dijkstra PU. Epidemiology of ankle and foot overuse injuries in sports: a systematic review. Scandinavian journal of medicine & science in sports. 2013 Dec;23(6):669-86.

- ↑ Zwerver J, Bredeweg SW, Van Den Akker-Scheek I. Prevalence of Jumper’s knee among nonelite athletes from different sports: a cross-sectional survey. The American journal of sports medicine. 2011 Sep;39(9):1984-8.

- ↑ DiFiori JP, Benjamin HJ, Brenner JS, Gregory A, Jayanthi N, Landry GL, Luke A. Overuse injuries and burnout in youth sports: a position statement from the American Medical Society for Sports Medicine. British journal of sports medicine. 2014 Feb 1;48(4):287-8.

- ↑ Stovitz SD, Johnson RJ. “Underuse” as a cause for musculoskeletal injuries: is it time that we started reframing our message?. British journal of sports medicine. 2006 Sep 1;40(9):738-9.

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 Lynch SA. Assessment of the injured ankle in the athlete. Journal of athletic training. 2002 Oct;37(4):406.

- ↑ Kannus P. Structure of the tendon connective tissue. Scandinavian journal of medicine & science in sports. 2000 Dec;10(6):312-20.

- ↑ ClickViewSports Injuries: Classification And ManagementAvailable from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=FKbia_VElek&feature=emb_logo. Accessed on 5/8/20