Lateral Collateral Ligament Injury of the Knee

Original Editors - Wouter Claesen

Top Contributors - Abbey Wright, Heleen Van Cleynenbreugel, Beverly Klinger, Kim Jackson, Darrell Blommaert, Admin, Wouter Claesen, Michelle Lee, Leana Louw, Daphne Jackson, Fasuba Ayobami, Celine De Wolf, 127.0.0.1, Wanda van Niekerk, Rishika Babburu, Evan Thomas and Naomi O'Reilly

Definition/Description[edit | edit source]

The lateral collateral ligament (LCL) or fibular collateral ligament, is one of the major stabilizers of the knee joint with a primary purpose of preventing excess varus and posterior-lateral rotation of the knee. Although less frequent than other ligament injuries, an injury to the lateral collateral ligament (LCL) of the knee is most commonly seen after a high-energy blow to the anteromedial knee, combining hyperextension and extreme varus force. The LCL can also be injured with a non-contact varus stress or non contact hyperextension. The LCL most commonly occurs in sports (40%) with high velocity pivoting and jumping such as soccer basketball, skiing, football or hockey. Tennis and gymnastics have been shown to have the highest likelihood of an isolated LCL injury.[1]

The LCL can be sprained (grade I), partially ruptured (grade II) or completely ruptured (grade III) .[2] The LCL is rarely injured alone and therefore additional damage of the anterior cruciate ligament (ACL), posterior cruciate ligament (PCL), and posterior-lateral corner (PLC) is common along with the LCL when the lateral knee structures are injured[1] [2][3].

Clinically Relevant Anatomy[edit | edit source]

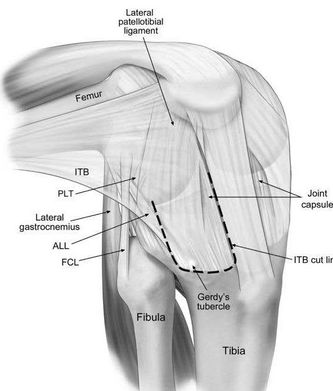

The LCL is a cord-like structure of the arcuate ligament complex, together with the biceps femoris tendon, popliteus muscle and tendon, popliteal meniscal and popliteal fibular ligaments, oblique popliteal, arcuate and fabellofibular ligaments and lateral gastrocnemius muscle[3][4].

The LCL is a strong connection between the lateral epicondyle of the femur and the head of the fibula, with the function to resist varus stress on the knee and tibial external rotation and thus a stabilizer of the knee. When the knee is flexed to more than 30°, the LCL is loose. The ligament is strained when the knee is in extension.[2]

See LCL anatomy for more detailed anatomy.

Epidemiology/Etiology[edit | edit source]

In the United States, 25% of the patients who present to the emergency room with acute knee pain have a collateral ligament injury. Adults aged between 20-34 and 55-65 years old have been shown to have the highest incidence. Of the collateral ligament injuries, MCL injuries are more commonly seen over LCL injuries. Limited studies have shown that isolated LCL injuries occur more often in women and in high contact sports[1].

Characteristics/Clinical Presentation[edit | edit source]

Acute

Patients with an acute LCL injury will present with a history of an acute incident which most commonly consisted of a blow to the medial knee while in full extension or extreme non contact varus bending. Pain, swelling and ecchymosis are often present at the lateral joint line along with difficulty in full weight bearing. Less common complaints consist of a thrust gait, foot kicking during mid stance, paresthesia down the lateral lower extremity as well as weakness and/or foot drop.[1][2]

Upon evaluation, a patient with an acute LCL injury may present with reduced ROM, instability/giving way during weight bearing as well weakness of the quadriceps (inability to perform a straight leg raise). The patient will present with pain as well as increased carbs movement when performing a Varus Stress Test.[2]

Sub-Acute

Patients who present with a sub-acute LCL injury will present with lateral knee pain, stiffness with end of range flexion or extension, overall weakness and possible instability/giving way.

Chronic

Patients with a chronic LCL injury will present with unspecific knee pain, significant weakness throughout the entire kinetic chain as well as potential instability and mal-adaptive movement patterns[4].

Differential Diagnosis[edit | edit source]

Due to its close proximity to surrounding structures, LCL injuries often occur along with other ligamentous injuries, including ACL, PCL, and PLC, and is frequently seen along with knee dislocations. Although not as common, meniscal tears/injuries can also occur with an LCL injury. Other diagnoses such as a Popliteus avulsion, Iliotibial Band Syndrome, and Distal hamstring tendinopathy need to be ruled out. [3]

Physical Exam[edit | edit source]

Information gathered during a subjective assessment will provide vital information necessary to making a diagnosis. Performing a comprehensive physical exam will allow the clinician to make the most appropriate differential diagnosis. Upon observation, patients with a suspected LCL injury will present with swelling, ecchymosis and possible increased warmth along the lateral joint line. A full ROM assessment should be performed as well as careful consideration to palpation along the lateral joint line. When possible, a gait analysis should be performed to identify the classic 'varus thrust' finding that is common in LCL injuries. An isolated LCL injury is uncommon therefore special tests should be performed to determine associated ligamentous, meniscal, or soft tissue injuries.[1]

Objective Assessment:

- Observation

- Palpation

- Active range of movement (ROM)

- Muscle testing

- Gait analysis

- Special tests

- Neurological Exam (if required)

Special Tests:

- Varus Stress Test- The most useful special test when assessing a LCL injury. With the femur stabilized, a varus force is applied with special attention to the lateral joint line. The test is first performed in 30 degrees flexion. Increased laxity or gapping is indicative of an LCL injury with possible PLC involvement. Test is then performed with knee in full extension. Improved stability indicates an isolated LCL injury while continued gapping is a positive test for LCL and PLC injury.

- External Rotation Recurvatum Test- With the patient in supine, a supra patellar force is applied while the great toe is used to lift and externally rotate the tibia. Excessive hyperextension when compared to the uninvolved limb is indicative of a positive test.

- Posterolateral Drawer Test- With the patient in prone, the knee is flexed to 90 degrees and externally rotated 15 degrees. The examiner then provides a posterior force to the femoral condyles. Excessive Posterolateral translation is a positive test and indicative of a PLC injury.

- Reverse Pivot Shift- With the patient in prone, the examiner slowly extends the knee while providing a valgus and external rotating force. The test is positive if a 'clunk' is felt at 30 degrees. Test must be performed bilaterally, as false-positives have been identified on the non-involved limb.

- Dial Test- With the patient in prone, the examiner stabilizes the femur while the lower limb is externally rotated. The test is performed bilaterally at 30 degrees and 90 degrees of knee flexion. Ten degrees or more of external rotation is a positive test and indicative of a PLC injury.

*Due to the likelihood of other ligamentous involvement, the Anterior and Posterior Drawer Tests as well as Patellar dislocation special tests should be performed.[1]

Varus Stress Test video provided by Clinically Relevant

Classification of Injury:[1]

LCL injuries are classified in to three grades depending on severity.

Grade I: Mild Sprain

- Mild tenderness and pain over the lateral collateral ligament

- Usually no swelling

- The varus test in 30° is painful but doesn’t show any laxity (< 5 mm laxity)

- No instability or mechanical symptoms present

Grade II: Partial Tear

- Significant tenderness and pain on the lateral and posterolateral side of the knee

- Swelling in the area of the ligament

- The varus test is painful and there is laxity in the joint with a clear endpoint. (5 -10mm laxity)

Grade III: Complete Tear

- The pain can vary and can be less than in grade II

- Tenderness and pain at the lateral side of the knee and at the injury

- The varus test shows a significant joint laxity (>10mm laxity)

- Subjective instability

- Significant swelling

Outcome Measures[edit | edit source]

- International Knee Documentation Committee Subjective Knee Form

Diagnostic Imaging[edit | edit source]

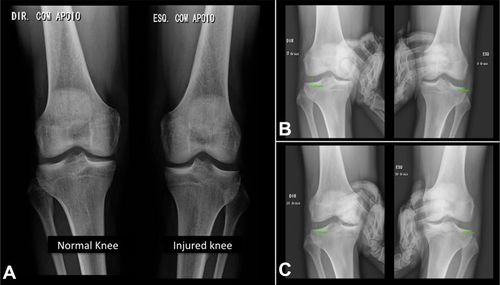

- Radiograph- AP and Lateral radiographs are used to rule out associated structural injuries such as fibular head fractures/avulsions (arcuate sign), tibial spine avulsions, or lateral tibial plateau (segond fracture). If an arcuate sign or segond fracture is evident it is indicative of a PLC injury and further investigation on the LCL is warranted. Varus and Posterior kneeling stress images are used to determine severity of LCL and PLC injuries. [1]

Radiographic images comparing the normal (right) and injured (left) sides: (A) anteroposterior (AP) view; (B) AP stress view, 0° of flexion; (C) AP stress view, 30° of flexion. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6348520/

Radiographic images comparing the normal (right) and injured (left) sides: (A) anteroposterior (AP) view; (B) AP stress view, 0° of flexion; (C) AP stress view, 30° of flexion. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6348520/

- MRI- Considered the gold standard in diagnosing LCL and PLC injuries. Coronal and Sagittal weighted T1 and T2 images have a 90% sensitivity and specificity in picking up an LCL injury. [1]

- Ultrasound- An effective tool used when a rapid diagnosis of LCL injury is needed. Upon evaluation, an LCL injury may be evident if a thickened and hypo echoic LCL is present. If there is a complete tear, an ultrasound may show increased edema, dynamic laxity, and/or a lack of fiber continuity of the LCL. [1]

Medical Management[edit | edit source]

Grade 1 and 2: Acutely, a grade 1 and 2 LCL injury can be treated with rest, ice, compression and NSAIDs [1]. Conservative management of LCL injuries is most commonly followed in grade I or II sprains[5]. Patients should be non-weightbearing for the first week and continue in a hinged-brace for the following 3 to 6 weeks while performing functional rehabilitation in order to maintain medial and lateral stability.[1]

Grade 3: Acutely, a grade 3 LCL injury should also be treated with rest, ice, compression and NSAIDs [1]. Grade III sprains are more severe with the possibility of the anterior cruciate, posterior cruciate ligaments or posterolateral corner also being damaged. In this case, surgery is needed to prevent further instability of the knee joint.[6] Recent literature shows that reconstruction surgery is the best treatment option for grade 3 LCL injuries with a goal of achieving a stable, well-aligned knee with normal biomechanics [1][7]. Surgical management of isolated LCL injuries involves reconstruction of the LCL using a semitendinosus autograft [1].

- Post operative rehabilitation can involve an altered weight-bearing status for the first six weeks. This is likely to be partial weight-bearing but when extensive additional surgery has been undertaken it could be non-weight bearing[5]. A knee immobiliser may also be used to limit valgus/varus stresses on the knee as well as stop the knee flexing during gait. Early ROM exercises should be encouraged in a non-weight bearing position. After the initial post-operative phase, normal rehab can start as detailed in the physiotherapy management. It is useful to note that if a meniscal repair is also done deep squats should be avoided for the initial four months.[5]

Physiotherapy Management [edit | edit source]

For general management see: Ligament injury management

As with other ligament injuries such as ACL repairs or ruptures a milestone-based approach can be undertaken, however, normal soft tissue healing timescales should be kept in mind when designing rehab programs[5].

Acute Management [5]

- POLICE or RICE

- Analgesia

- Oedema (swelling) management

- Bracing in a knee immobiliser or adjustable brace which allows limited flexion but full extension.

- Offloading of the knee as required with crutches

- Early mobilisation of the knee should be encouraged

- Quadriceps activation exercises

- Ensure straight leg raise with no lag

- Electrical stimulation can also prevent the muscles wasting due to immobilisation.[8]

Sub-Acute Management

- Full weight-bearing - gait re-education

- Full AROM of knee

- Progression of strength exercises of quadriceps, glutes, gastrocnemius and hamstrings.

- Closed chain strength work

Long-Term Management

- Proprioception work

- Plyometric exercises - with focus on reducing excessive varus or external tibial rotation[9].

- High-level strengthening and loading of the whole kinetic chain

- Aerobic conditioning

Clinical Bottom Line[edit | edit source]

An injury to the lateral collateral ligament of the knee can be caused by a varus stress or hyperextension to the knee joint. Additional damage to the ACL, PCL, posterio-lateral corner and lateral knee structures is possible with an LCL injury. In case of a grade III sprain, reconstructive surgery may be needed to prevent further instability of the knee joint. Conservative management should always be the initial treatment choice.

References[edit | edit source]

- ↑ 1.00 1.01 1.02 1.03 1.04 1.05 1.06 1.07 1.08 1.09 1.10 1.11 1.12 1.13 1.14 Yaras RJ, O'Neill N, Yaish AM. Lateral Collateral Ligament (LCL) Knee Injuries. StatPearls [Internet]. 2020 Aug 4.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 2.4 Logerstedt DS, Snyder-Mackler L, Ritter RC, Axe MJ, Godges JJ. Knee stability and movement coordination impairments: knee ligament sprain: clinical practice guidelines linked to the international classification of functioning, disability, and health from the Orthopaedic Section of the American Physical Therapy Association. Journal of Orthopaedic & Sports Physical Therapy. 2010 Apr;40(4):A1-37.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 Recondo JA, Salvador E, Villanúa JA, Barrera MC, Gervás C, Alústiza JM. Lateral stabilizing structures of the knee: functional anatomy and injuries assessed with MR imaging. Radiographics. 2000 Oct;20(suppl_1):S91-102.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 Ricchetti ET, Sennett BJ, Huffman GR. Acute and chronic management of posterolateral corner injuries of the knee. Orthopedics. 2008 May 1;31(5).

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 5.3 5.4 Lunden JB, BzDUSEK PJ, Monson JK, Malcomson KW, Laprade RF. Current concepts in the recognition and treatment of posterolateral corner injuries of the knee. journal of orthopaedic & sports physical therapy. 2010 Aug;40(8):502-16.

- ↑ Pekka Kannus, MD Nonoperative treatment of Grade II and III sprains of the lateral ligament compartment of the knee , Am J Sports Med January 1989 vol. 17 no. 1 83-88

- ↑ Cooper JM, McAndrews PT, LaPrade RF. Posterolateral corner injuries of the knee: anatomy, diagnosis, and treatment. Sports medicine and arthroscopy review. 2006 Dec 1;14(4):213-20.

- ↑ Dr Pekka Kannus, Markku Järvinen, Nonoperative Treatment of Acute Knee Ligament Injuries, sports medicine, 1990, Volume 9, p244-260 (level of evidence: 3a)

- ↑ Mohamed O, Perry J, Hislop H. Synergy of medial and lateral hamstrings at three positions of tibial rotation during maximum isometric knee flexion. The Knee. 2003 Sep 1;10(3):277-81.