Lateral Ligament Injury of the Ankle

Original Editor - The Open Physio project

Top Contributors - Ilona Malkauskaite, Shaimaa Eldib, Kim Jackson, Rachael Lowe, Admin, Samuel Adedigba, Wanda van Niekerk, Nupur Smit Shah, Naomi O'Reilly and WikiSysop

Introduction[edit | edit source]

Lateral ligament injuries are perhaps one of the most common sports-related injuries seen by physiotherapists. Lateral ankle sprains are thought to be suffered by men and women at approximately the same rates; however, it is suggested that female interscholastic and intercollegiate basketball players have a 25% greater risk of incurring grade I ankle sprains than their male counterparts. More than 23 000 ankle sprains have been estimated to occur per day in the United States, which equates to one sprain per 10 000 people daily[1].

Lateral ankle sprains are referred to as inversion ankle sprains or as supination ankle sprains. It is usually a result of a forced plantar flexion/inversion movement, the complex of ligaments on the lateral side of the ankle is torn by varying degrees. Although the ankle sprain is a relatively benign injury, inadequate rehabilitation can lead to residual symptoms after lateral ankle sprain affect 55% to 72% of patients at 6 weeks to 18 months[2]. The frequency of complications and breadth of longstanding symptoms after ankle sprain has led to the suggestion of a diagnosis of the sprained ankle syndrome [3].

Individuals who suffer numerous repetitive ankle sprains have been reported as having functional and mechanical instability and increased likelihood of re-injury[4][5]. Care should also be taken to avoid missing the less common causes of ankle pain, namely; small fractures around the ankle and foot (e.g. Pott's fracture) and straining or rupture of the muscles around the ankle (e.g. calf, peroneii, tibialis anterior).

Functional Anatomy:[edit | edit source]

Bones:[edit | edit source]

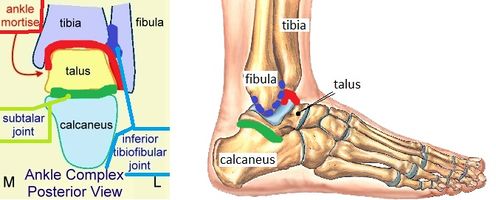

The bones that make up the ankle joint include the distal tibia and fibula (the medial and lateral malleolus, respectively) and the talus.

Joints:[edit | edit source]

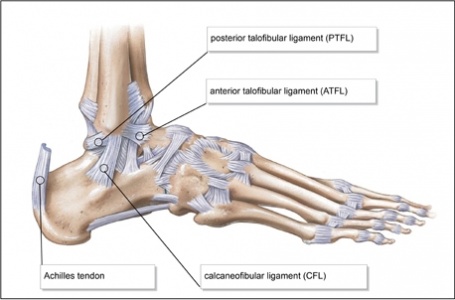

- The Ankle Complex consists of 3 articulations[6] The talocrucal (ankle joint) ( Mortise joint) is a hinge joint between the inferior surface of the tibia and the superior surface of the talus. It allows the movements of plantarflexion and dorsiflexion(sagittal plane).The talocrural joint receives ligamentous support from a joint capsule and several ligaments, including the anterior talofibular ligament (ATFL), posterior talofibular ligament (PTFL), calcaneofibular ligament (CFL), and deltoid ligament. The ATFL, PTFL, and CFL support the lateral aspect of the ankle.[5]. Plantarflexion is the least stable position of the ankle joint, which explains why the majority of ankle injuries occur in this position.

- The inferior tibiofibular joint is the articulation between the distal parts of the tibia and fibula, where a small amount of rotation (transverse plane) is possible.Injury in this joints called (high ankle sprains[5]). The joint is stabilized by a thick interosseous membrane and the anterior and posterior inferior tibiofibular ligaments.

- The subtalar joint is an articulation between the talus and calcaneus and allows the movements of eversion and inversion (frontal plane). It also has an important role as a shock absorber[5]. The ligamentous support of the subtalar joint is extensive, it is divided into 3 groups: (1) deep ligaments, (2) peripheral ligaments, and (3) retinacula[7].

Ligaments:[edit | edit source]

- The lateral ligaments of the ankle, composed of the anterior talo-fibular ligament (ATFL), the calcaneo-fibular ligament (CFL) and the posterior talo-fibular ligament.

- The medial (deltoid) ligaments is much stronger than the lateral ligament and is therefore injured much less frequently.

Muscles:[edit | edit source]

The following muscles are involved in moving the ankle joint:

- Calf group, made up of the gastrocnemius and soleus;

- Peroneus longus and peroneus brevis;

- Tibialis anterior.

Innervation:[edit | edit source]

The motor and sensory supplies to the ankle complex stem from the lumbar and sacral plexes. The motor supply to the muscles comes from the tibial, deep peroneal, and superficial peroneal nerves. The sensory supply comes from these 3 mixed nerves and 2 sensory nerves: the sural and saphenous nerves. [8]

Risk factors:[edit | edit source]

Body mass index, slow eccentric inversion strength, fast concentric plantar flexion strength, passive inversion joint position sense, and the reaction time of the peroneus brevis were associated with significantly increased risk of lateral ankle sprain.[9]

Assessment of the ankle joint[edit | edit source]

The aims of the physical examination are to determine the:

- Amount of instability present by assessing the grade of the sprain;

- Loss of Range of motion (ROM);

- Loss of the muscle strength;

- Level of reduced Proprioception.

Observation[edit | edit source]

The physical examination begins with general observation of the foot and ankle.[10] Any signs of injury, inflammation, colour changes of the skin or atrophy/hypertrophy of the muscles are noted. After that, observation of the foot and ankle continues in two different positions non-weight bearing (n-WB) and weight bearing (WB) positions. Make a note of the gait pattern, degree of limp (if any), facial expression on weight bearing and any other signs that may provide more information about the injury.

History[edit | edit source]

Taking an accurate history is an important step in determining the nature of the injury. A plantarflexion/inversion injury would indicate damage to the lateral ligament, whereas a dorsiflexion/eversion injury would indicate damage to the medial ligament. Previous history of injury on the same side will give clues as to whether the ankle was unstable to ,begin with, or that a previous injury wasn't properly rehabilitated. History of injury on the other side as well may indicate a biomechanical predisposition towards ankle injuries.

Instability and grade of sprain[edit | edit source]

Ligament sprains can be of the following grades:

- Grade 1 - mild, painful, minimal tearing of the ligament fibres;

- Grade 2 - moderate, painful, significant tearing of the ligament fibres;

- Grade 3 - severe, sometimes not painful, complete rupture of the fibres.

Range of motion (ROM)[edit | edit source]

ROM of the ankle needs to be assessed actively and passively. The movements to be assessed are:

- Plantarflexion and dorsiflexion;

- Inversion and eversion.

Palpation[edit | edit source]

An important aspect of the initial examination is to determine the exact site of the lateral ligament sprain, whether it's the ATFL, CFL or PTFL (usually damaged in that order). Palpating the lateral aspect of the ankle over the course of the various aspects of the ligament complex will provide detailed information on the exact location of the tear. Begin palpating gently as this can potentially be acutely painful for the patient.

Special tests[edit | edit source]

- Anterior drawer

- Talar tilt

- Proprioception

- An anterior drawer is done to test the integrity of the ATFL and CFL. With the ankle in plantarflexion, the heel is grasped with the tibia stabilised and drawn anteriorly.

- Talar tilt is done to assess the integrity of the ATFL and CFL laterally and the deltoid ligament medially. Again the heel is grasped, the tibia stabilised and the talus and calcaneus are moved laterally and medially.

- Proprioception can be assessed in any number of increasingly difficult ways, beginning with a simple single leg stance. The patient can do it on the normal side first, to allow the therapist to get an idea of what the normal is and then attempt on the injured side.

- Star Excursion Balance Test : This test is used for assessment and treatment purpose after ankle injury.

This test can be progressed by asking the patient to reach outside their base of support (BOS), rotating their neck or by closing their eyes. Moving onto a wobble board or any other unstable surface will allow the therapist to assess the patients ability to respond to a changing surface.

Functional movements[edit | edit source]

Functional movements such as lunges and hopping should be included in the assessment.

Differential diagnosis[edit | edit source]

A differential diagnosis must be carried out to exclude the possibility of the following, less common injuries:

- Ankle fracture (medial/lateral malleolus, distal tibia/fibular)

- Damage to the medial ligament

- Dislocated ankle

- Other soft tissue damage (peroneal tendons, muscle strain)

Ottawa Ankle Rules [11] provide useful guidance on determining the presence of a fracture. Bachmann et al in the systematic review found out that evidence supports the Ottawa ankle rules as an accurate instrument for excluding fractures of the ankle and mid-foot. [12]The instrument has a sensitivity of almost 100% and a modest specificity, and its use should reduce the number of unnecessary radiographs by 30-40%.

If a patient is unable to weight-bear immediately following the injury, an X-ray is indicated because of the risk of a clinically significant ankle fracture. Failure to use the Ottawa rules to assess for ankle fracture may be significant in any legal proceedings should they occur. Even though injuries to the lateral ligament are by far more common, be aware that there may be other injuries associated with the lateral ligament injury. Missing an associated injury may hamper a return to pre-injury level of functional activity and lead to the so-called “problem ankle”.

Treatment and rehabilitation[edit | edit source]

According to Green et, al, the overall quality of the existing Lateral Ankle Ligament Sprain Clinical Practice Guidelines is poor with the majority out of date. Also, several inconsistencies in the interpretation of the evidence between the CPG development group and an absence of consistent methodology of CPGs presents a barrier to implementation.[13]

Reduce pain and swelling[edit | edit source]

- Initial management (i.e. within the first 48-72 hours) of an acute lateral ligament injury is to reduce pain and swelling by following the RICE regimen; Rest, Ice, Compression and Elevation.

- If weight bearing (WB) is too painful, the patient can be given elbow crutches and be non-weight bearing (NWB) for 24 hours. However, it's important that at least partial weight bearing (PWB) is initiated relatively soon, together with a normal heel-toe gait pattern, as this will help to reduce pain and swelling.

- Gentle soft tissue massage can be performed to assist with the removal of oedema and gentle stretches, as long as this is pain free.

Restore ROM[edit | edit source]

As soon as pain allows, the patient should begin pain free active range of movement (ROM) exercises.

Restore strength[edit | edit source]

Eversion is especially important.

Restore proprioception[edit | edit source]

Proprioception training should begin as soon as pain allows during the rehabilitation programme.

Return to functional activity[edit | edit source]

Patients should be assessed for the ability to do the following activities pain free [14]:

- Twisting

- Jumping

- Hopping on one leg

- Running

- Figure of 8 running

Before returning to full functional activity the patient should have full range of pain free movement in the ankle, normal strength and normal proprioception. If returning to sports, the athlete should be encouraged to wear an ankle brace or to tape the ankle for a further 6 months to provide external support. Types of taping include a heel lock and figure of 6.

Resources[edit | edit source]

References[edit | edit source]

- ↑ The gender issue: epidemiology of ankle injuries in athletes who participate in basketball. Hosea TM, Carey CC, Harrer MF Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2000 Mar; (372):45-9.

- ↑ Fallat L, Grimm D J, Saracco J A. Sprained ankle syndrome: prevalence and analysis of 639 acute injuries. J Foot Ankle Surg. 1998;37:280–285

- ↑ Gerber J P, Williams G N, Scoville C R, Arciero R A, Taylor D C. Persistent disability associated with ankle sprains: a prospective examination of an athletic population. Foot Ankle Int. 1998;19:653–660.

- ↑ Instability of the foot after injuries to the lateral ligament of the ankle. Freeman MA J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1965 Nov; 47(4):669-77.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 5.3 Hertel, J. (2002). Functional anatomy, pathomechanics, and pathophysiology of lateral ankle instability. Journal of athletic training, 37(4), 364.

- ↑ Joints and movements of the foot: terminology and concepts. Huson A Acta Morphol Neerl Scand. 1987; 25(3):117-30.

- ↑ Viladot A, Lorenzo J C, Salazar J, Rodriguez A. The subtalar joint: embryology and morphology. Foot Ankle. 1984;5:54–66

- ↑ The subtalar joint: embryology and morphology. Viladot A, Lorenzo JC, Salazar J, Rodríguez A Foot Ankle. 1984 Sep-Oct; 5(2):54-66.

- ↑ Kobayashi T, Tanaka M, Shida M. Intrinsic Risk Factors of Lateral Ankle Sprain: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Sports Health. 2016 Mar-Apr;8(2):190-3.

- ↑ Hengeveld E, Banks K. Maitland's Peripheral Manipulation. Vol 2. Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone, 2014.

- ↑ Kyriacou H, Mostafa AM, Davies BM, Khan WS. Principles and guidelines in the management of ankle fractures in adults. Journal of Perioperative Practice. 2021 Nov;31(11):427-34.

- ↑ Bachmann LM, Kolb E, Koller MT, Steurer J, ter Riet G. Accuracy of Ottawa ankle rules to exclude fractures of the ankle and mid-foot: systematic review. BMJ. 2003;326(7386):417.

- ↑ Green T, Willson G, Martin D, Fallon K. What is the quality of clinical practice guidelines for the treatment of acute lateral ankle ligament sprains in adults? A systematic review. BMC musculoskeletal disorders. 2019 Dec 1;20(1):394.

- ↑ Vuurberg G, Hoorntje A, Wink LM, Van Der Doelen BF, Van Den Bekerom MP, Dekker R, Van Dijk CN, Krips R, Loogman MC, Ridderikhof ML, Smithuis FF. Diagnosis, treatment and prevention of ankle sprains: update of an evidence-based clinical guideline. British journal of sports medicine. 2018 Aug 1;52(15):956-.