Knee Osteoarthritis: Difference between revisions

Abbey Wright (talk | contribs) No edit summary |

Abbey Wright (talk | contribs) No edit summary |

||

| Line 153: | Line 153: | ||

=== Objective assessment: === | === Objective assessment: === | ||

After a thorough subjective | After a thorough subjective assessment it may be clear the diagnosis of the patient already, however, it is always necessary to perform an objective assessment to rule out differential diagnoses and provide objective outcome measures such as range of movement (ROM). | ||

* '''Observation of the knee:''' it may be enlarged, swollen or red if the OA is very reactive or irritated. | |||

Observation: | * '''Observation in general:''' movement patterns at rest and when performing simulations of daily activities such as getting up from and down on a chair | ||

* '''Gait assessment:''' use of walking aids may be required due to pain, is there any stiffness during gait, is there significant reduced weight bearing of the affected knee. | |||

Palpation: | * '''Palpation:''' swelling, temperature changes, joint line tenderness may all be present in an acutely aggravated OA knee | ||

* '''ROM:''' flexion and extension may be limited due to stiffness or formation of osteophytes in the joint | |||

* '''Strength:''' reduced strength is normal in an OA knee due to pain and deconditioning | |||

* '''Normal functional activities:''' such as climbing stairs may be affected | |||

* '''Balance:''' may be affected due to pain, this needs to be assessed to rule out [[falls]] risk. | |||

== Physical Therapy Management == | == Physical Therapy Management == | ||

Revision as of 16:19, 21 May 2020

Original Editors - Fien Selderslaghs, Laura Van Der Perren, Mirabella Smolders, Liese Magnus

Top Contributors - Mirabella Smolders, Laura Van Der Perren, Hamelryck Sascha, Abbey Wright, Laura Ritchie, Lucinda hampton, Kim Jackson, Jessica Davis, Fien Selderslaghs, Rachael Lowe, Bo Hellinckx, Venugopal Pawar, Admin, Vidya Acharya, Ophélie Schraepen, 127.0.0.1, Feebe Robyns, Joni Roesems, Candace Goh, WikiSysop, Aminat Abolade, Simisola Ajeyalemi, Robin Tacchetti, Rishika Babburu, Arthur Devoldere, Jelien Wouters, Evan Thomas, Anthony Mertens, Rucha Gadgil, Michelle Lee, Barb Clemes, Jess Bell, Kai A. Sigel and Sai Kripa

Introduction[edit | edit source]

Knee osteoarthritis (OA), also known as degenerative joint disease, is typically the result of wear and tear and progressive loss of articular cartilage. It is most common in elderly people and can be divided into two types, primary and secondary:

- Primary osteoarthritis - is articular degeneration without any apparent underlying cause.

- Secondary osteoarthritis - is the consequence of either an abnormal concentration of force across the joint as with post-traumatic causes or abnormal articular cartilage, such as rheumatoid arthritis (RA).

Osteoarthritis is typically a progressive disease that may eventually lead to disability. The intensity of the clinical symptoms may vary from each individual. However, they typically become more severe, more frequent, and more debilitating over time. The rate of progression also varies for each individual.

Common clinical symptoms include

- Knee pain that is gradual in onset and worse with activity,

- Knee stiffness and swelling,

- Pain after prolonged sitting or resting.

Treatment for knee osteoarthritis begins with conservative methods and progresses to surgical treatment options when conservative treatment fails. While medications can help slow the progression of RA and other inflammatory conditions, no proven disease-modifying agents for the treatment of knee osteoarthritis currently.[1]

Epidemiology[edit | edit source]

OA is the most common disease of the joints worldwide, with the knee being the most commonly affected joint in the body. [3] It mainly affects people over the age of 45.

OA can lead to pain and loss of function, but not everyone with radiographic findings of knee OA will be symptomatic: in one study only 15% of patients with radiographic findings of knee OA were symptomatic[1][3].

- OA affects nearly 6% of all adults

- Women are more commonly affected than men[3]

- Roughly 13% of women and 10% of men 60 years and older have symptomatic knee osteoarthritis.[1]

- Among those older than 70 years of age, the prevalence rises to as high as 40%.[1]

- Prevalence will continue to increase as life expectancy and obesity rises.

Etiology[3][edit | edit source]

Knee OA is classified as either primary or secondary, depending on its cause:

- Primary knee OA is the result of articular cartilage degeneration without any known reason. This is typically thought of as degeneration due to age as well as wear and tear.

- Secondary knee OA is the result of articular cartilage degeneration due to a known reason. Possible Causes of Secondary Knee OA:

- Obesity

- Joint hypermobility or instability

- Malpositioning of the joint e.g. valgus/varus posture

- Previous injury to the joint e.g. fracture along articular surface (tibial plateau fracture)

- Congenital defects

- Immobilisation and loss of mobility

- Family history

- Metabolic causes e.g. rickets

Relevant Anatomy[edit | edit source]

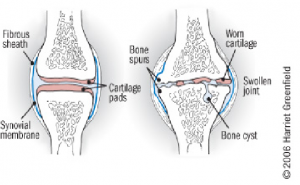

The knee (art. genus) is a synovial joint, which consists of 2 articulations.

- Tibiofemoral joint is located between the convex femoral condyles and the concave tibial condyles (the primary joint).[4]

- Patellofemoral joint between the Femur and the Patella

OA can occur in either or both of these articulations of the knee, it is usual that the patellofemoral joint is affected first.[5]

Pathological Process[6][7][edit | edit source]

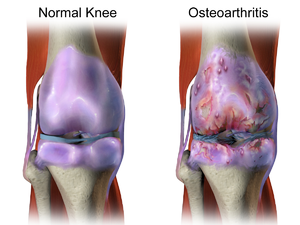

The process of osteoarthritis affects the articular cartilage (mainly type II) that covers the articular surfaces of bone[1].

Articular cartilage is normally maintained in a healthy equilibrium of chemical reactions, however, when OA starts to develop the reactions are disrupted leading to changes in the collagen of the cartilage:

- Disruption in the equilibrium which results in the disorganised pattern of collagen, and loss of articular cartilage elasticity.

- This results in cracking and fissuring of the cartilage which leads to erosion of the articular surface.[1]

- Cartilage that has been damaged, cannot recover.

- The cartilage will continue to wear away

- Once the cartilage has worn away; bony surfaces will start to be affected

- The bone will expand and spurs (osteophytes) will develop.

It is common for ligament laxity and muscle atrophy to also occur as the disease progresses. [8]

Characteristics/Clinical Presentation[edit | edit source]

Signs of knee OA are:

- Pain on movement

- Stiffness, particularly early morning stiffness

- Loss of range of movement

- Pain after prolonged sitting or lying

- Pain on joint line palpation

- Joint enlargement.[9]

We can subdivide knee OA in 5 grades:

- Grade 0: This is the “normal” knee health

- Grade 1: Very minor bone spur growth and is not experiencing any pain or discomfort.

- Grade 2: This is the stage where people will experience symptoms for the first time. They will have pain after a long day of walking and will sense a greater stiffness in the joint. It is a mild stage of the condition, but X-rays will already reveal greater bone spur growth. The cartilage will likely remain at a healthy size.

- Grade 3: Moderate OA. Frequent pain during movement, joint stiffness will also be more present, especially after sitting for long periods and in the morning. The cartilage between the bones shows obvious damage, and the space between the bones is getting smaller.

- Grade 4: This is the most severe stage of OA. The joint space between the bones will be dramatically reduced, the cartilage will almost be completely gone and the synovial fluid will be decreased. This stage is normally associated with high levels pain and discomfort during walking or moving the joint.[10]

Diagnosis[edit | edit source]

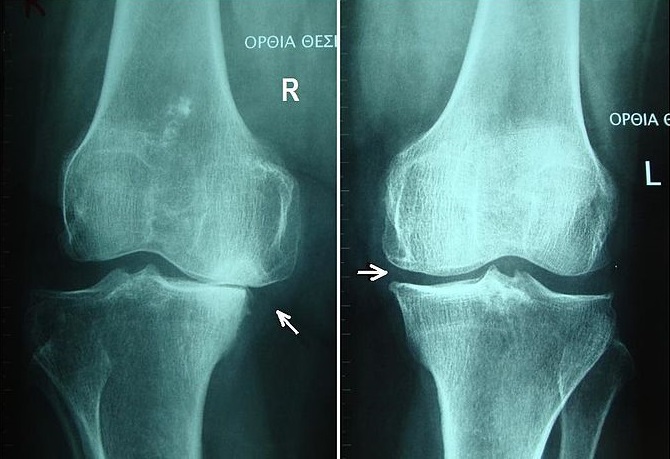

The diagnosis can be established by clinical examination, and it can be confirmed by X-rays.

Diagnostic Tests[edit | edit source]

Blood Tests; to help determine the type of arthritis

Physical examination: see below

X-ray: A basic X-ray is used to research breakdown of cartilage, narrowing of joint space, forming of bone spurs and to exclude other causes of pain in the affected joint.

Arthrocentesis: This is a procedure which can be performed at the doctor’s office. A sterile needle is used to take samples of joint fluid which can then be examined for cartilage fragments, infection or gout.

Arthroscopy: is a surgical technique where a camera is inserted in the affected joint to obtain visual information about the damage caused to the joint by the OA.

MRI. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). Provides a view that offers better images of cartilage and other structures to detect early abnormalities typical of osteoarthritis[11].

Radiographic Findings of OA[edit | edit source]

- Joint space narrowing

- Osteophyte formation

- Subchondral sclerosis

- Subchondral cysts[1]

- Early stages of OA shows a minimal unequal joint space narrowing.

- In severe OA the joint line may disappear completely (see image 2).[9]

Treatment/Management[edit | edit source]

Treatment for knee OA can be broken down into conservative and surgical management.

Initial treatment always begins with conservative modalities and moves to surgical treatment once conservative management has been exhausted. There is a wide range of conservative modalities is available for the treatment of knee OA. These interventions do not alter the underlying disease process, but their goal is to reduce pain and optimise function for as long as possible.[1]

Conservative Treatment Options[edit | edit source]

The primary treatment for OA knee conservatively is exercise therapy within physiotherapy.[12] Physiotherapy normally involves

- Patient education

- Exercise therapy

- Activity modification

- Advice on weight loss

- Knee bracing

- The first-line treatment for all patients with symptomatic knee osteoarthritis includes patient education and physiotherapy. A combination of supervised exercises and a home exercise program have been shown to have the best results. These benefits are lost after 6 months if the exercises are stopped.[12]

- Weight loss is valuable in all stages of knee OA. It is indicated in patients with symptomatic OA with a body mass index greater than 25. The best recommendation to achieve weight loss is with diet control and low-impact aerobic exercise.

- Knee bracing in OA can be used. Offloading-type braces which shift the load away from the involved knee compartment. This can be effective when there is a valgus or varus deformity.

Other non-physiotherapy based interventions include pharmacological management[1]:

- Acetaminophen

- Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs)

- COX-2 inhibitors

- Glucosamine and chondroitin sulfate

- Corticosteroid injections

- Hyaluronic acid (HA)

- Drug therapy alongside physiotherapy should be the first-line treatment for patients with symptomatic OA. There are a wide variety of NSAIDs available, however, caution should be used when prescribing NSAIDs due to their side effects.[13]

- Glucosamine and chondroitin sulfate are available as dietary supplements. They are structural components of articular cartilage, and the thought is that a supplement will aid in the health of articular cartilage. No strong evidence exists that these supplements are beneficial in knee OA.

- Intra-articular corticosteroid injections may be useful for symptomatic knee OA.

- Intra-articular hyaluronic acid injections (HA) injections are another inject-able option. Local delivery of HA into the joint acts as a lubricant and may help increase the natural production of HA in the joint.

Differential Diagnosis[1][edit | edit source]

- Meniscal pathology

- Patellar-femoral pain syndrome

- Gout and Pseudogout

- Rheumatoid arthritis

- Septic arthritis[14]

- Hip OA

- Referred lower back pain

- Ligament injury ACL or PCL rupture

Examination[edit | edit source]

Subjective assessment[edit | edit source]

Take a proper history of pain including when the pain started if it was gradual or sudden, if there was any previous injury to the same knee.

The common subjective symptoms of knee OA are:

- Early morning stiffness

- Dull achy pain

- Pain after sitting

- Pain after increased activity

- Reduced mobility

- Difficulty weight bearing on the affected leg

- Decrease in the abilities of daily functioning

- Sleep may be affected (screen red flags appropriately)

Objective assessment:[edit | edit source]

After a thorough subjective assessment it may be clear the diagnosis of the patient already, however, it is always necessary to perform an objective assessment to rule out differential diagnoses and provide objective outcome measures such as range of movement (ROM).

- Observation of the knee: it may be enlarged, swollen or red if the OA is very reactive or irritated.

- Observation in general: movement patterns at rest and when performing simulations of daily activities such as getting up from and down on a chair

- Gait assessment: use of walking aids may be required due to pain, is there any stiffness during gait, is there significant reduced weight bearing of the affected knee.

- Palpation: swelling, temperature changes, joint line tenderness may all be present in an acutely aggravated OA knee

- ROM: flexion and extension may be limited due to stiffness or formation of osteophytes in the joint

- Strength: reduced strength is normal in an OA knee due to pain and deconditioning

- Normal functional activities: such as climbing stairs may be affected

- Balance: may be affected due to pain, this needs to be assessed to rule out falls risk.

Physical Therapy Management[edit | edit source]

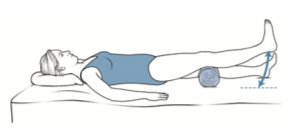

Physical therapy can be your first line of defence for managing knee OA symptoms. Pain is a common symptom that occurs in many levels (e.g. mild, moderate and severe). Exercises[15] have been proven to be effective as pain management and also improving physical functioning (e.g. muscle strengthening and aerobic condition) on short term.[9] In order to perform it correctly, exercises have to take place under the supervision of a health care professional such as a physiotherapist. When properly instructed these exercises can be performed at home, though research has shown that group exercise combined with home exercise is more effective.[16] Aerobic walking, strengthening of the quadriceps, resistance training and tai chi are a few examples of exercises that can be efficacious for knee OA patients.[9]

Main Goals of Physiotherapy[edit | edit source]

- Reduce knee pain and inflammation.

- Normalise knee joint range of motion.

- Strengthen lower kinetic chain: esp quadriceps (esp VMO) and hamstrings, and including calves, hip and pelvis muscles.

- Improve your patellofemoral alignment and function.

- Normalise muscle length via stretching and mobilisations.

- Improve proprioception, agility and balance.

- Improve function eg walking, squatting.

- Educate regarding activity modification, if necessary.

- Educate regarding weight loss (if appropriate) and general fitness/exercise.

- Teach in use of gait aide of appropriate.

Land-based exercises are ideal for most clients. Strongly recommend by guidelines[17] for knee OA, land-based exercises are appropriate for all clients regardless of their age, structural disease severity, functional status or pain levels. Exercise has also been found to be beneficial for other comorbidities and overall health. Walking, muscle-strengthening exercise, stationary cycling, Hatha yoga and Tai Chi are examples of such exercises. Individualised exercise program are always the best, taking into account the person’s preference, capability, and the availability of resources and local facilities. Realistic goals should be set. Dosage should be progressed with full consideration given to the frequency, duration and intensity of exercise sessions, number of sessions, and the period over which sessions should occur. Attention should be paid to strategies to optimise adherence.

The video below gives 5 good home exercises for people with knee osteoarthritis.

When being treated, other aspects such as self-management and education, are of crucial importance as well.[15] There are various forms of therapeutic interventions that may or may not be helpful for patients with knee OA as listed in the guidelines and include: Hydrotherapy; manual therapy; massage therapy; thermotherapy; electrotherapy; ultrasound; bracing; surgery and postoperative exercises. See table below.

| Hydrotherapy |

Is a non-invasive and non-interventional therapeutic intervention that is recommended in international guidelines.[9] Although there is some contradictory evidence hydrotherapy can be useful in cases where pain is too grave to exercise on dry land. Many consider water-based exercises as a good preparation of exercise ashore. [19] Knee osteoarthritis mostly affects the weight-bearing joints and leads, amongst other things, to pain and muscle weakness. The strength of muscles around the affected joints can be built up by graduated exercises making use of buoyancy and floats (in the later stage of the treatment).[20] , [21].[21] It has been shown that water buoyancy can reduce the weight that joints, bones and muscles have to carry.[22] Range of motion can also be maintained and increased[21]using the freedom of movement offered by the water with the support given by the buoyancy. Functional difficulties of osteoarthritis patients are generally walking and climbing stairs and much can be done to re-educate such patients in the pool.[21]. Many patients are more mobile in water than on land and this gives them greater confidence and a sense of achievement. Examples of hydrotherapeutic exercises:

Despite the controversy, other studies show that aquatic exercises (Aquatherapy) have some short-term beneficial effects.[23]. Thus, the results indicate that hydrotherapy is applicable and efficient for patients with knee OA. Though there are short-term effects, long-term effects have yet to be investigated.[22] Aquatic exercise may therefore be considered as the first part of an exercise therapy program to get particularly disabled patients introduced to training.[23] |

| Manual therapy |

Has proven effective to locate and eliminate factors like pain and joint immobility. However, it is only effective when combined with active exercise. This progress can enable further or advanced exercises. One study proved that manual therapy can relieve pain and decrease stiffness.[24] |

| Massage therapy |

Until recently massage has been proven not to be effective in the case of osteoarthritis. One study has shown that this therapeutic intervention, which uses both Swedish (including effleurage, pétrissage, fricition, tapotement and vibration) and the standard massage technique is safe, reduces pain and improves function.[25] |

| Thermotherapy |

Contrary to heat application, which did not have significant effects, ice massage and packs have showed to improve both ROM (range of motion) and physical function. Whether ice packs relieve pain is still unknown, thus further investigation is needed.[26] |

| Electrotherapy |

Transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation is an example of electrotherapy, which has beneficial effects on relieving pain and improving physical function.[9], [27]TENS is a stimulation that uses electrical currents, which are applied directly to the skin and surrounding the knee.[9] Despite the positive effects, electro stimulation is not effective on improving strengthening of the quadriceps.[23] |

| Ultrasound |

Older studies have claimed that this therapeutic option is not beneficial in the treatment of knee osteoarthritis. However, newer studies have shown that ultrasound reduces pain and improves the aerobic condition.[27], [28] |

| External Support Devices |

Braces: Knee braces are used as a therapeutic procedure for patients with OA that involves the medial and lateral tibiofemoral compartments. Their purpose is to diminish the articular contact stress in those compartments. There are various types of braces [9]

Taping: Has proven to be slightly effective in decreasing pain and disability for patients with knee OA.[20] These beneficial effects are short-termed. |

| Surgery and post-operative exercise |

Surgery is only recommended when therapies are not effective. There are various types of knee OA surgery[9]:

Post- operative exercises are very much recommended. Exercises to improve the function of the new joint and muscle strengthening are most effective.[16] |

Medical Managment[edit | edit source]

In some cases, patients with knee arthritis choose to undergo knee surgery for knee arthritis. The most common forms of surgery for this condition are

- Therapeutic Injections,

- Arthroscopes,

- Osteotomy[1]

- Unicompartmental knee arthroplasty

- Total knee replacements.

- If symptoms are reaching an unmanageable level and treatment results have plateaued surgical options may be of benefit.

The below video gives a good guide to both surgical and non surgical options and why or when they are offered.

Conservative Treatment[edit | edit source]

Ottawa Panel of evidence suggests the use of therapeutic exercises or exercises with manual therapy to be most beneficial for patients with knee OA. [30]Deyle et al. found that knee mobilization gave statically improvements in WOMAC and 6 minute walk tests for both 4 week, 8 week, and 1 year follow up.[31]

A CPR (clinical prediction rules) for patients with knee pain to indicate those patients have knee OA, and which patients are likely to have short term benefits from hip mobilizations (confirmed by studies[32][33]) found this CPR:

1. Hip and groin parasthesia

2. Groin pain

3.Passive knee flexion less than 122 degrees

4.Passive hip IR less than 17 degrees

5.Pain with hip distraction”.[32]

If the patient has 2 variables then the positive likely hood ratio is 12.9.

Conclusion[edit | edit source]

Knee osteoarthritis (OA) is best managed by an interprofessional team that consists of an orthopedic surgeon, rheumatologist, physical therapist, dietitian, a pain specialist, and internist.

- The disorder has no cure and thus attempts should be made to prevent progression of the disorder.

- The patient should be referred to a dietitian for weight loss and to physical therapy to regain joint function and muscle strength.

- Treatment for knee osteoarthritis begins with conservative methods and progresses to surgical treatment options when conservative treatment fails.

- The pharmacist should look at the patient's medications to ensure there are no interactions and that the dosing and indications are all correct.

- While medications can help slow the progression of RA and other inflammatory conditions, no proven disease-modifying agents for the treatment of knee osteoarthritis currently exist.[1]

References[edit | edit source]

- ↑ 1.00 1.01 1.02 1.03 1.04 1.05 1.06 1.07 1.08 1.09 1.10 1.11 Hsu H, Siwiec RM. Knee Osteoarthritis.2019 Available from:https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK507884/ (last accessed 28.2.2020)

- ↑ rBioventus Stages of knee OA Available from: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=BBqjltHNOrc&feature=youtu.be (last accessed 17.11.2019)

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 Michael JW, Schlüter-Brust KU, Eysel P. The epidemiology, etiology, diagnosis, and treatment of osteoarthritis of the knee. Deutsches Arzteblatt International. 2010 Mar;107(9):152.

- ↑ Jennifer Reft. Knee Osteokinematics and Arthokinematics. Available from: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=EyhiCvWER0Y [last accessed 07/12/2014]

- ↑ Brukner P, Clarsen B, et al. Brukner & Khan's Clinical sports medicine 5th edition. McGraw Hill Education; 2017; p777

- ↑ Buckwalter JA, Mankin HJ, Grodzinsky AJ. Articular cartilage and osteoarthritis. Instructional Course Lectures-American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons. 2005;54:465.

- ↑ Pearle AD, Warren RF, Rodeo SA. Basic science of articular cartilage and osteoarthritis. Clinics in sports medicine. 2005 Jan 1;24(1):1-2.

- ↑ E. Schulte, et al., General anatomy and musculoskeletal system, Atlas of Anatomy, 2006: 372-373

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 9.2 9.3 9.4 9.5 9.6 9.7 9.8 RK Arya, Vijay Jain, Osteoarthritis of the knee joint: An overview, Journal Indian Academy of Clinical Medicine, 2013, 14(2): 154-62

- ↑ Lespasio MJ, Piuzzi NS, Husni ME, Muschler GF, Guarino AJ, Mont MA. Knee osteoarthritis: a primer. The Permanente Journal. 2017;21.

- ↑ Osteoarthritis Diagnosis Arthritis Foundation Available from: https://www.arthritis.org/about-arthritis/types/osteoarthritis/diagnosing.php (last accessed 17.11.2019)

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 Collins NJ, Hart HF, Mills KA. Osteoarthritis year in review 2018: rehabilitation and outcomes. Osteoarthritis and cartilage. 2019 Mar 1;27(3):378-91.

- ↑ Aweid O, Haider Z, Saed A, Kalairajah Y. Treatment modalities for hip and knee osteoarthritis: A systematic review of safety. Journal of Orthopaedic Surgery. 2018 Nov 8;26(3):2309499018808669.

- ↑ E. RINGDAHL, et al., Treatment of Osteoarthritis, American Family Physician, 2011, 83(11):1287-1292.

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 T.E. McAlindon et al., OARSI guidelines for the non-surgical management of knee osteoarthritis, Osteoarthritis Research Society International, 2014, 22: 363-388

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 Supplementing a home exercise program with a class-based exercise program is more effective than home exercise alone in the treatment of knee osteoarthritis ,C. J. McCarthy, P. M. Mills1, R. Pullen, C. Roberts, A. Silman and,J. A. Oldham, Rheumatology 2004;43:880–886

- ↑ RACGP Guidelines for hip and knee arthritis Available from: https://www.racgp.org.au/download/Documents/Guidelines/Musculoskeletal/guideline-for-the-management-of-knee-and-hip-oa-2nd-edition.pdf (last accessed 18.11.2019)

- ↑ Bob and Brad 5 Proven Exercises for Knee Osteoarthritis or Knee Pain- Do it Yourself Available at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=T3qKHLP8fVo&feature=youtu.be (last accessed 17.11.2019)

- ↑ Bartels et al., Aquatic exercise for the treatment of knee and hip osteoarthritis (Review),The Cochrane Library 2007, Issue 4

- ↑ 20.0 20.1 Hinman, R.S., Heywood, S.E. (2007). Aquatic physical therapy for hip and knee osteoarthritis: results of a single-blind randomized controlled trial. Journal of Physical Therapy 87 (1), 32-43

- ↑ 21.0 21.1 21.2 21.3 Wang, T., Belza, B., Elaine Thompson, F., Whitney, J.D., Bennett, K. (2007) Effects of aquatic exercise of flexibility, strength and aerobic fitness in adults with osteoarthritis of the hip or knee. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 57 (2), 141-152

- ↑ 22.0 22.1 L.E. Silva et al., Hydrotherapy Versus Conventional Land-Based Exercise for the Management of Patients With Osteoarthritis of the Knee: A Randomized Clinical Trial, Physical Therapy Journal, 2008, 88(1): 12-21

- ↑ 23.0 23.1 23.2 A Clinical Trial of Neuromuscular Electrical Stimulation in Improving Quadriceps Muscle Strength and Activation Among Women With Mild and Moderate Osteoarthritis, Riann M. Palmieri-Smith, Abbey C. Thomas, Carrie Karvonen-Gutierrez, MaryFran Sowers, Physical Therapy - Volume 90 Number 10 October 2010

- ↑ G.D. Deyle et al., Physical Therapy Treatment Effectiveness for Osteoarthritis of the Knee: A Randomized Comparison of Supervised Clinical Exercise and Manual Therapy Procedures Versus a Home Exercise Program, Physical Therapy Journal, 2005, 85(12): 1301-1317

- ↑ A.I. Perlman et al., Massage Therapy for Osteoarthritis of the Knee, Archives of Internal Medicine, 2006, 166: 2533-2538

- ↑ L. Brosseau et al., Thermotherapy for treatment of osteoarthritis (Review), The Cochrane Library, 2011, 10: 1-23

- ↑ 27.0 27.1 N.C. Mascarin et al., Effects of kinesiotherapy, ultrasound and electrotherapy in management of bilateral knee osteoarthritis: prospective clinical trial, BMC Musculoskeletal Disorders, 2012, 13: 182-191

- ↑ A. Loyola-Sánchez et al., Efficacy of ultrasound therapy for the management of knee osteoarthritis: a systematic review with meta-analysis, Osteoarthritis Research Society International Journal, 2010, 18: 1117-1126

- ↑ Mayo Clinic Mayo Clinic's Approach to Knee Arthritis - Both Surgical and Non-Surgical Available from: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=4Mk9GZ7-Dz8 (last accessed 17.11.2019)

- ↑ No authors listed. Ottawa panel evidence-based clinical practice guidelines for therapeutic exercises and manual therapy in the management of osteoarthritis. Phys Ther. 2005 Sep; 85 (9):907-71.

- ↑ Deyle Gail, Henderson Nancy, Matekel Robert, Ryder Micahel, Garber Matthew, Allison Stephen. Effectiveness of Manual Physical therapy and Exercise in Osteoarthritis of the Knee A Randomized, Controlled Trial

- ↑ 32.0 32.1 Linda L Currier, Paul J Froehlich, Scott D Carow, Ronald K McAndrew, Amy V Cliborne, Robert E Boyles, Liem T Mansfield and Robert S Wainner. Development of a Clinical Prediction Rule to Identify Patients With Knee Pain and Clinical Evidence of Knee Osteoarthritis Who Demonstrate a Favorable Short-Term Response to Hip Mobilization. PHYS THER Vol. 87, No. 9, September 2007, pp. 1106-1119

- ↑ Cliborne Amy, Rhon Dan, Judd Coy, Fee Terrance, Matekel Robert, Whitman Julie, Roberts Maj. Clinical hip tests and a functional squat test in patients with knee osteoarthritis: Reliability, Prevalence of Positive Test Findings, and Short-Term Response to Hip Mobilization. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 2004;34(11):676-685. doi:10.2519/jospt.2004.1432

37. Seyed Mansour Rayegani 1 , Seyed Ahmad Raeissadat 1 , Saeed Heidari 2 , Mohammad Moradi-Joo 3,4. Safety and Effectiveness of Low-Level Laser Therapy in Patients With Knee Osteoarthritis: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. S12–S19 2017 Aug 29.