Heterotopic Ossification: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

No edit summary |

||

| Line 132: | Line 132: | ||

#Improve ROM (if still limited) | #Improve ROM (if still limited) | ||

#Return to previous levels of activity | #Return to previous levels of activity | ||

== References == | == References == | ||

Revision as of 02:40, 24 October 2021

Original Editors - Bruce Tan as part of the from Bellarmine University's Pathophysiology of Complex Patient Problems project.

Top Contributors - Bruce Tan, Morgan Yoder, Hannah McCabe, Naomi O'Reilly, Lucinda hampton, Admin, Elaine Lonnemann, WikiSysop, Kim Jackson, 127.0.0.1 and Wendy WalkerIntroduction[edit | edit source]

Heterotopic ossification is frequently observed in the rehabilitation population. It consists of the formation of mature, lamellar bone in extraskeletal soft tissue where bone does not usually exist. Patient populations at risk of developing heterotopic ossification include patients with burns, strokes, spinal cord injuries, traumatic amputations, joint replacements, and traumatic brain injuries.[1]

- Lesions range from small clinically insignificant foci of ossification to large deposits of bone that cause pain and restriction of function.

- The most common presentation is with pain around the ossification site[2]

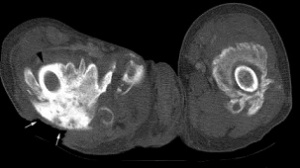

Image 1: CT scan showing heterotopic ossification of proximal femur

Etiology[edit | edit source]

The exact mechanism of HO in traumatic and neurogenic HO is unknown, but 2 common factors precede the formation of HO, the first being trauma or an inciting neurological event.

- Traumatic (fracture, arthroplasty, muscular trauma, joint dislocation, burns). In total joint arthroplasty, HO most commonly occurs for the replacement of hips, knees, elbow, and shoulder. Chronic muscular trauma leads to what is traditionally known specifically as traumatic myositis ossificans. The most common sites for traumatic myositis ossificans are the quadriceps femoris muscle and the brachialis muscle.

- Neurogenic (stroke, SCI, TBI, brain tumors). The most common sites for neurogenic HO are the hips, elbows (extensor side), shoulders, and knees. Uncommon sites of HO that may be encountered in a rehabilitation setting are incisions, kidneys, uterus, corpora cavernosum, and the gastrointestinal (GI) tract. The exact cause and mechanism of neurogenic HO are unknown.

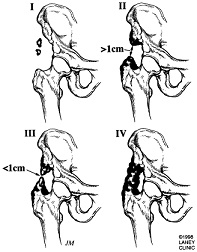

Image 2: Radiograph showing heterotopic ossification of the hip

Risk factors for developing HO

- Spasticity, older age, pressure ulcer, the presence of deep vein thrombosis (DVT), having a tracheostomy, long bone fractures, prior injury to the same area, edema, immobility, long-term coma, and severity of injury (trauma, TBI, SCI, stroke).

- High/moderate risk factors in the THA population include men with bilateral THA, prior history of HO, ankylosing spondylitis, diffuse idiopathic hyperostosis, or Paget's disease.[1]

Epidemiolgy[edit | edit source]

- HO is twice as common in males versus females, but it is noted that females older than 65 years old have an increased risk of developing HO.

- The incidence of neurogenic HO is 10% to 20%.[1]

- Following lower extremity amputation: 7%[3]

- Following SCI: 20% (ranges reported from 20-40%)[3]

- Following THA: 55%[4]

- Following elbow fracture and/or dislocation: 90%[5]

Clinical Diagnosis[edit | edit source]

Clinical signs and symptoms of HO may appear as soon as 3 weeks or up to 12 weeks after initial musculoskeletal trauma, spinal cord injury, or other precipitating events.[6] The first sign of HO is generally loss of joint mobility and subsequently loss of function. Other findings that may suggest the presence of HO include swelling, erythema, heat, local pain, palpable mass, and contracture formation. In some cases, a fever may be present.[4]

Presentation

- Symptoms: painless loss of ROM, interferes with ADL, CRPS symptoms, fever

- Inspection: warm, painful, swollen joint; may have effusion; skin problems (decubitus ulcers from contractures around skin, muscles, ligaments, skin maceration and hygiene problems)

- Motion: decreased joint ROM; joint ankylosis; with HO after TKA, might develop quad muscle snapping or patella instability

- Neurovascular: peripheral neuropathy; HO often impinges on adjacent NV structures[7]

Differential Diagnoses[edit | edit source]

The initial inflammatory phase of HO may mimic other pathologies such as cellulitis, thrombophlebitis, osteomyelitis, or a tumorous process.[8][9]

Other differential diagnoses include DVT, septic arthritis, hematoma, or fracture. DVT and HO have been positively associated. This is thought to be due to the mass effect and local inflammation of the HO, encouraging thrombus formation. The thrombus formation is caused by venous compression and phlebitis.[4]

Diagnosis[edit | edit source]

Diagnosis is made radiographically with soft tissue ossification with sharp demarcation from surrounding soft tissues.[7]

Associated Co-Morbidities

[edit | edit source]

The most common conditions found in conjunction with heterotopic ossification:[9] [10]

- Ankylosing spondylitis

- Rhuematoid arthritis[11]

- Hypertrophic osteoarthritis

- Diffuse idiopathic skeletal hyperostosis

- Paget's disease

- Quadriplegia and paraplegia

Treatment[edit | edit source]

HO is best managed by an interprofessional team that includes orthopedic nurses. The condition is not only difficult to diagnose because of lack of specific markers but its treatment is not satisfactory.

Current treatment recommendations consist of mobilization with ROM exercises, indomethacin, etidronate, and surgical resection.

- Early treatment with a passive range of motion exercises should be implemented once the presence of HO is confirmed to prevent ankylosing of joints.

- Absolute treatment consists of surgical resection of mature bone once the HO has fully matured. This can be 12 to 18 months after the initial presentation.

- Surgical consultation with an orthopedic surgeon is warranted only if there will be an improvement in function as demonstrated by mobility, transfers, hygiene, and ADLs.

- Indomethacin and etidronate are also used to help arrest bone formation in HO, but efficacy in the traumatic brain injury population has not been clearly proven (see below).

- The most effective treatment option in the TBI population is surgical resection. In the SCI population, the most effective NSAID treatment regiments are either Rofecoxib 25 mg per day for 4 weeks or indomethacin 75 mg daily for 3 weeks.[1]

Medications[edit | edit source]

The two types of medications shown to have both prophylactic and treatment benefits are as follows:

- Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs: NSAIDS

Indomethacin (two-fold action)

1. Inhibition of the differentiation of mesenchymal cells into osteogenic cells (direct)

2. Inhibition of post-traumatic bone remodeling by suppression of prostaglandin-mediated response (indirect) and anti-inflammatory properties - Biphosphonates:

Three-fold action

1. Inhibition of calcium phosphate precipitation

2. Slowing of hydroxyapatite crystal aggregation

3. Inhibition of the transformation of calcium phosphate to hydroxyapatite.

Surgical interventions[edit | edit source]

The two main goals of surgical intervention are to

- Alter the position of the affected joint

- Improve its range of motion (ROM).[12]

Rehabilitation Post-Operatively: It is recommended that a rehabilitation program should start within the first 24 hours after surgery. The program should last for 3 weeks to prevent adhesion.[11]

Prognosis[edit | edit source]

Complications of HO present itself through decreased function and mobility, peripheral nerve entrapment, and pressure ulcers.

- Up to 70% of cases involving HA are asymptomatic.

- Ankylosis, vascular compression, and lymphedema can also be complications manifested in HO.

- Prognosis is generally good after surgery. Mean time from injury to surgery is 3.6 years. Once the surgery is performed, studies have shown that average ROM in the hip can improve from 24.3 to. After surgery, improvement was maintained in follow up 6 months after surgery. Complications from surgical resection of HO, such as infection, severe hematoma, and DVT

Physical Therapy Management[edit | edit source]

Physical therapy has been shown to benefit patients suffering from heterotopic ossification. Pre-operative PT can be used to help preseve the structures around the lesion. ROM exercises (PROM, AAROM, AROM) and strengthening will help prevent muscle atrophy and preserve joint motion.

Clinical note: caution must be taken when working with patients with known heterotopic lesions. Therapy which is too aggressive can aggravate the condition and lead to inflammation, erythema, hemorrhage, and increased pain.

Post-operative rehabilitation has also shown to benefit patients with recent surgical resection of heterotopic ossification. The post-op management of HO is similar to pre-op treatment but much more emphasis is placed on edema control, scar management, and infection prevention. Calandruccio et al. outlined a rehabilitation protocol for patients who underwent surgical excision of heterotopic ossification of the elbow. The phases of rehab and goals for each phase are as follows:[3]

Phase I (Week 1)

Goals:

- Prevent infection

- Protect and decrease stress on surgical site

- Decrease pain

- Control and decrease edema

- ROM to 80% of affected joint

- Maintain ROM of joint proximal and distal to surgical site

Phase II (2-8 weeks)

Goals:

- Reduce pain

- Manage edema

- Encourage limited ADL performances

- Promote scar mobility and proper remodeling

- Promote full ROM of affected joint

- Encourage quality muscle contractions

Phase III (9-24 weeks)

Goals:

- Self-manage pain

- Prevent flare-up with functional activities

- Improve strength

- Improve ROM (if still limited)

- Return to previous levels of activity

References[edit | edit source]

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 Sun E, Hanyu-Deutmeyer AA. Heterotopic Ossification.Available: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK519029/(accessed 24.10.2021)

- ↑ Radiopedia HO Availasble: https://radiopaedia.org/articles/heterotopic-ossification(accessed 24.10.2021)

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 Hsu JE, Keenan MA. Current review of heterotopic ossification. UPOJ 2010; 20: 126-130.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 Mavrogenis AF, Soucacos PN, Papagelopoulos PJ. Heterotopic Ossification Revisited. Orthopedics. 2011Jan;34(3):177.

- ↑ Dalury DF, Jiranek WA. The incidence of heterotopic ossification after total knee arthroplasty. Journal of Arthroplasty 2004; 19: 447-457.

- ↑ Shehab D, Elgazzar AH, Collier BD. Heterotopic ossification. Jour of Nuclear Medicine 2002; 43: 346-353.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 Orthobullets HO Available: https://www.orthobullets.com/pathology/8044/heterotopic-ossification(accessed 24.10.2021)

- ↑ Firoozabadi R, Alton T, Sagi HC. Heterotopic Ossification in Acetabular Fracture Surgery. Journal of the American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons. 2017;25(2):117–24.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 Bossche LV, Vanderstraeten G. Heterotopic ossification: a review. J Rehabil Med 2005; 37: 129-136.5. Pape HC et al. Current concepts in the development of hetetrotopic ossification. Journ Bone and Joint Surg 2004; 86: 783-787.

- ↑ McCarthy EF, Sundaram M. Heterotopic ossification: a review. Skeletal Radiol 2005; 34: 609-619.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 Foruria AM, Augustin S, Morrey BF, Sanchez-Sotelo Joaquin. Heterotopic Ossification After Surgery for Fractures and Fractures-Dislocations Involving the Proximal Aspect of the Radius or Ulna. The Journal of Bone and Joint Surgery, Incorporated. 2015May15;95-A(10):e66(1)-e66(7).

- ↑ Pape HC et al. Current concepts in the development of hetetrotopic ossification. Journ Bone and Joint Surg 2004; 86: 783-787.