Overview of Traumatic Brain Injury

Original Editor - Wendy Walker and Anna Ziemer

Lead Editors - Wendy Walker, Naomi O'Reilly, Kim Jackson, Rachael Lowe, Vidya Acharya, Lucinda hampton, Kalyani Yajnanarayan, Stacy Schiurring, George Prudden, Shaimaa Eldib, Nicole Hills, Lauren Lopez, Mande Jooste, 127.0.0.1, Tony Lowe, Nupur Smit Shah, WikiSysop, Simisola Ajeyalemi, Karen Wilson and Uchechukwu Chukwuemeka

Introduction[edit | edit source]

Worldwide, traumatic brain injury (TBI) is a leading cause of death and disability in persons aged <45 years. Per the World Health Organization (WHO), approximately sixty-nine million people experience a TBI annually. TBI is a significant concern to public health and rehabilitation professionals as it is associated with both acute and long-term disabilities.[1]

Acquired brain injury or head injury are broad terms describing an array of injuries that occur to the scalp, skull, brain, and underlying tissue and blood vessels in the head. Acquired brain injury does not include damage to the brain resulting from neurodegenerative disorders like Multiple Sclerosis (MS) or Parkinson’s Disease. Acquired brain injuries are broadly classified into; traumatic brain injury derived from an external source and non-traumatic brain injury derived from either an internal or external source.

| Traumatic Brain Injury | Non-Traumatic Brain Injury |

|---|---|

| Falls | Stroke e.g. Haemorrhage, Clot |

| Assaults | Infectious Disease e.g. Meningitis, Encephalitis |

| Motor Vehicle Accidents | Seizure |

| Sport / Recreation Injury | Electric Shock |

| Abusive Head Trauma e.g Shaken Baby Syndrome | Tumours |

| Gunshot Wounds | Toxic Exposure |

| Workplace Injury | Metabolic Disorders |

| Child Abuse | Neurotoxic Poisoning e.g. carbon monoxide, lead exposure |

| Domestic Violence | Lack of Oxygen e.g. drowning, choking, hypoxic & anoxic injury |

| Military Actions eg. Blast Injury | Drug Overdose |

Acquired brain injuries can also be congenital in origin[2], resulting in potentially lifelong rehabilitation needs from a well-trained and educated interdisciplinary team.

Traumatic Brain Injury[edit | edit source]

Traumatic Brain Injury (TBI) is “an alteration in brain function, or other evidence of brain pathology, caused by an external force”.[3] It occurs when an external force impacts the brain, and often is caused by a blow, bump, jolt or penetrating wound to the head. However, not all blows or jolts to the head cause traumatic brain injury, some just cause bony damage to the skull, without subsequent injury to the brain. Mild traumatic brain injury is now more commonly referred to as assessment and management of concussion.

Traumatic brain injury does not always result in obvious motor impairment. Other hidden symptoms related to cognition and behaviour can also occur with traumatic brain injury. The fact that the population living with traumatic brain injury are largely invisible and are not outspoken about their needs plus widespread misunderstanding of the impact of related conditions, has earned the traumatic brain injury the name the “silent epidemic”. [4]

Various healthcare service-related factors can influence the impact of traumatic brain injury on individuals and society. These include implementation of algorithm-based best practices in emergency and intensive care medicine, implementation of a systematic approach to neurorehabilitation, improved access to related services and adequate related funding. Where these issues are not addressed, people living with a traumatic brain injury can be prevented from capitalising on the most valuable time for rehabilitative treatment which results in significantly increased care costs. Longer-term related unemployability and loss of income affect both traumatic brain injury survivors and family members providing care. These issues lead to an underestimated social cost of traumatic brain injury.

Causes[edit | edit source]

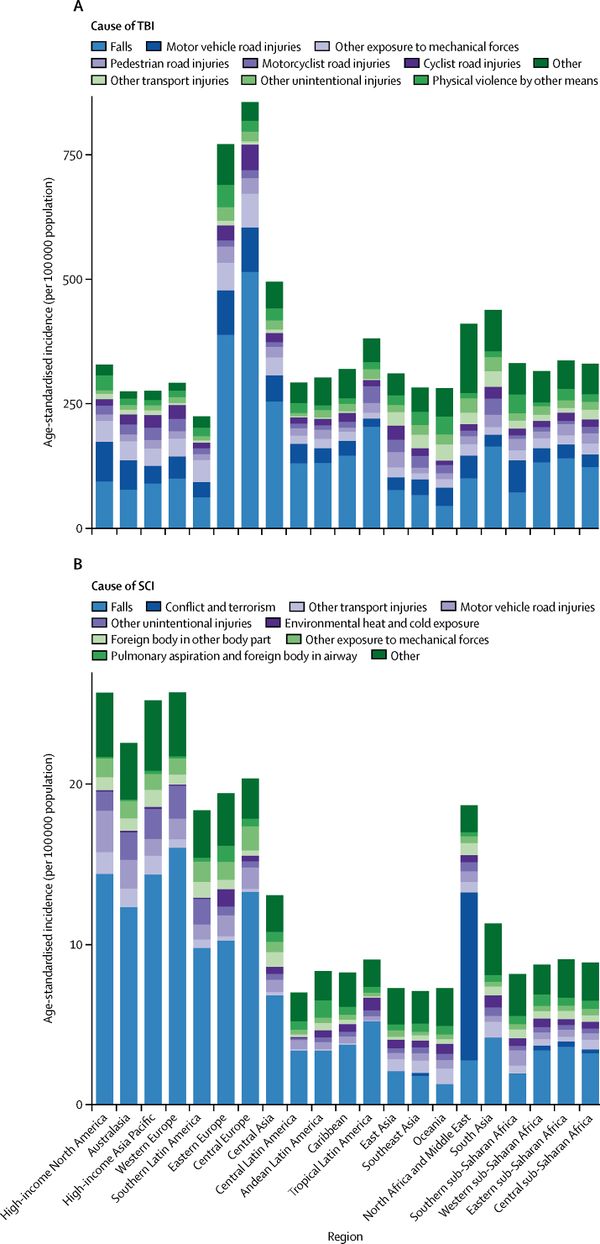

The two most common causes of traumatic brain injury are Falls and road traffic accidents (RTA), which includes vehicle collisions, pedestrians being hit by a vehicle, vehicle-cyclist and car-motorcyclist collisions as well as bicycle and motorbike crashes which do not involve another vehicle. Until recently, road traffic accidents were the primary cause of traumatic brain injury, but an international study published in 2013 reported that "falls have now surpassed road traffic incidents as the leading cause of this injury". [6]

Traumatic brain injury in sport has become more recognised with clearly emerging long-term consequences. Many professionals have become involved in developing evidence related to the complexity of symptoms, the impact of the repetitive nature on brain health and long-term prognosis of sport-related concussion. Evidence for sports-specific assessment and treatment as well as the role of sport in brain degenerative diseases are emerging and this is promoting steps to increase the safety of those participating in sports like rugby, football, boxing, horse riding, and racing, American football, or ice hockey. A systematic review carried to find whether the head guards protect against injuries to boxers indicates that concussions and other head injuries are present in boxing with or without head guards. A headguard is effective at protecting against facial cuts and skull fractures, and a strategy to protect boxers might be to introduce regulations that lower the frequency and force of blows to the head by incorporating technology into head guards will help understand the type and size of force sustained by boxers, however, further studies on boxing, headguards, and head injury prevention are needed.[7]

Global conflicts have exposed the military and civilian participants to new types and severities of injuries, but also led to the development of improved subacute care and life-saving and neurosurgical procedures,[8] which have also benefited civil healthcare services.

Incidence[edit | edit source]

Traumatic brain injury has been a public health problem for many years and will remain a major source of death and severe disability in the future. According to the World Health Organisation by 2020 traumatic brain injury will surpass many diseases as the major cause of death and disability. We are currently observing an increasing number of survivors of traumatic brain injuries due to advances in emergency medicine and intensive care and also due to decreasing fatalities as a result of safety and preventative measures such as decreased speed limits and the use of helmets and protective equipment. Traumatic brain injury continues to be a critical health and socioeconomic problem worldwide across low and high-income countries due to its life-long consequences and as it can affect people at any age. Socioeconomic change in low and middle-income countries due to urbanisation and mechanisation also drives an increase in traumatic brain injury in these regions.

One study found that TBI was "a major cause of death and disability on the United States, contributing to about 30% of all injury deaths". [9] A 2010 study looked at data from several nations and reported that "each year 235,000 Americans are hospitalised for non-fatal TBI, 1.1 million are treated in emergency departments, and 50,000 dies. A report from Victoria, Australia of traumatic brain injury numbers from 2006-2014 found a decline in the incidence of motor vehicle related severe traumatic brain injury, suggesting that road injury prevention measures have been effective, but targeted measures for reducing the incidence of major head injuries from falls should be explored as in the over 65 age bracket these are on the rise. [10] The Northern Finland birth cohort found that 3.8% of the population had experienced at least 1 hospitalisation due to traumatic brain injury by 35 years of age. The Christchurch, New Zealand birth cohort found that by 25 years of age 31.6% of the population had experienced at least 1 traumatic brain injury, requiring medical attention including hospitalisation, emergency department, or physician office. An estimated 43.3% of Americans have residual disability 1 year after a traumatic brain injury, with the most recent estimate of the prevalence of US civilian residents living with disability following hospitalisation with traumatic brain injury is 3.2 million". [11]

We are witnessing a change in traumatic brain injury distribution for age groups with children and older people being the highest risk populations; and gender with males being the most at risk between 10 and 20 years old and females between 70 and 80 [4]. There is also a change in the mechanisms contributing to injury with falls increasingly contributing to traumatic brain injury and blast-related injury being the most common mechanism of battlefield sustained traumatic brain injury.

The incidence amongst children and adolescents creates new challenges in the field of traumatic brain injury with often-overlooked symptoms such as behavioural change or educational difficulties and vulnerability to criminalisation.

Access to emergency and neurosurgical services influences mortality and recovery outcomes after traumatic brain injury across all world regions. In lower-income countries, this access is limited and results in higher numbers of severe disability post -raumatic brain injury.

Mechanism of Injury[edit | edit source]

Closed Head Injury[edit | edit source]

- Often occurs as a result of RTA, or a blow to the head, or a fall where the head strikes the floor or another hard surface.

- In closed head injury, the skull is not penetrated, but it is frequently fractured.

- Generally, there is both focal and diffuse axonal damage.

Open Head Injury[edit | edit source]

- This is caused by a penetrating wound, eg. by a weapon or from a bullet.

- In these cases, the skull is penetrated.

- The brain injury is usually largely focal axonal damage.

Deceleration Injury[edit | edit source]

- This frequently occurs in RTA, when rapid deceleration occurs as the skull meets a stationary object, causing the brain to move inside the skull.

- Mechanical brain injury occurs due to axonal shearing, contusion and brain oedema.

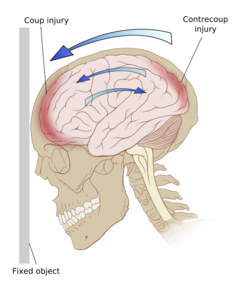

Coup-Contracoup Injury[edit | edit source]

Coup Injury[edit | edit source]

This occurs beneath the point of impact may be associated with a skull fracture at the site of impact

Contracoup Injury[edit | edit source]

This occurs when the impact is sufficient to cause the brain to move within the skull; the brain moves in the opposite direction, and hits the opposite side of the skull, causing bruising.

Coup-Contracoup Injury[edit | edit source]

This is a frequent occurrence where opposite poles of the brain suffer injury.

Classification[edit | edit source]

There are various determinants utilised to classify traumatic brain injury. The clinical presentation and prognosis depend on the individual nature of the injury with different types of traumatic brain injury often coexisting. The classification is important for acute management, treatment and prognosis as well as neurorehabilitation requirements. Classifications may be based on:

- pathoanatomic ie. what damage has occurred and where in the brain;

- injury severity, typically using the Glasgow Coma Scale as the measure where a score of 8 or less is defined as severe traumatic brain injury; or

- by the physical mechanism causing the injury, which can be categorised as contact or "impact" loading when the head is struck or strikes an object, as opposed to non-contact or "inertial" loading, which is when the brain moves within the skull.

Clinical Presentation[edit | edit source]

The presentation depends on the areas of the brain which have been damaged. Spasticity is one of the early signs of traumatic brain injury which often develops within a week post-injury. Symptoms include hypertonicity and spasm of the affected muscles and an increase in deep tendon reflexes. The severity of spasticity can range from mild stiffness of the muscles to severe and often painful muscle spasms.

Signs and Symptoms[edit | edit source]

Traumatic brain injury can have wide-ranging physical, cognitive, psychological and physiological effects occurring immediately or after a period of time has elapsed. The symptoms might differ depending on the severity of the traumatic brain injury, but some are not specific to the type of injury.

| Physical Symptoms | Sensory Symptoms | Cognitive Symptoms |

|---|---|---|

| With or without loss of consciousness. If loss of consciousness: a few seconds to a few minutes | ||

| Headache | Blurred Vision | State of being dazed, confused or disoriented |

| Nausea or Vomiting | Ringing in the Ears | Memory or concentration deficits |

| Fatigue or Drowsiness | Bad taste in the mouth or changes in the ability to smell | Mood changes or mood swings |

| Problems with speech | Sensitivity to light or sound | Irritability |

| Difficulty sleeping or sleeping more than usually | Feeling depressed or anxious | |

| Dizziness or loss of balance | Fatiguability | |

| Physical Symptoms | Sensory Symptoms | Cognitive Symptoms |

|---|---|---|

| Loss of consciousness from several minutes to hours or days | ||

| Persistent headache or headache that worsens | Blurred vision | Coma and other disorders of consciousness |

| Repeated vomiting or nausea | Double vision | Profound confusion |

| Convulsions or seizures | Ringing in the ears | Irritability |

| Dilation of one or both pupils of the eyes | Bad taste in the mouth or changes in the ability to smell | Agitation, combativeness or other unusual behaviour |

| Clear fluid or blood draining from the nose or ears | Sensitivity to light or sound | Sad or depressed mood |

| Sudden swelling or bruises behind the ears or around eyes | Fatiguability | |

| Inability to awaken from sleep | ||

| Weakness or numbness | ||

| Loss of coordination or balance | ||

| Irregular breathing | ||

| Difficulty speaking | ||

Diagnostic Procedures[edit | edit source]

Post-acute traumatic brain injury, all patients are encouraged to undergo an urgent neurological examination in addition to a surgical examination.[12] Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI) and Computerised Tomography (CT) scanning are frequently used in order to image the brain. CT scanning is indicated in the very early stages of post-injury. A CT scan can show potential fractures and can detail haemorrhages and haematomas in the brain, as well as contusions and swelling. An MRI is often used once the patient is medically stable to give a more detailed view of their brain tissue. The EFNS (European Federation of Neurological Societies) guidelines provide a basis for the use of CT scans based on clinical signs and symptoms (see below).

| Classification | Characteristics | Referral for CT? |

|---|---|---|

| Mild |

|

No |

| Category 1 |

|

No |

| Category 2 |

|

Yes |

| Category 3 |

|

Yes |

| Moderate |

|

Yes |

| Severe |

|

Yes |

| Critical |

|

Yes |

| Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS), Canadian CT in Head Injury Patients Prediction Rule (CHIP Rule) | ||

Medical Management[edit | edit source]

The aims of initial emergency and early medical management are to limit the development of secondary brain damage while providing the best conditions for recovery from any reversible damage that has already occurred. This involves establishing and maintaining a clear airway with adequate oxygenation and replacement fluids to ensure good peripheral circulation with adequate blood volume.

Surgical Interventions[edit | edit source]

Emergency surgery is often required to decompress the injured brain and minimise damage:

- Surgery to remove the haematoma and thus reduce pressure on brain tissue.

- Removal of part of the skull in order to relieve pressure.

- Surgical repair of severe skull fractures, and/or removal of skull fragments from brain tissue.

- Insertion of intracranial pressure (ICP) Monitoring Device.[13]

Medical Interventions[edit | edit source]

Medication may also be used to limit secondary damage to the brain:

- Coma-inducing medication may be given, as a brain in coma requires far less oxygen. This is therapeutic where oxygen and nutrient supply to the brain is restricted by compressed blood vessels and increased cerebral pressure.

- Diuretics, given intravenously, can be used to reduce the amount of fluid in soft tissues and thus help reduce pressure on the brain.

- Anti-epileptic medication is often provided in the early stages to avoid any additional brain damage, which may be caused if a seizure were to occur.[13]

Physiotherapy Management[edit | edit source]

Just as two people are not exactly alike, no two brain injuries are exactly alike. Therefore, the approach to neurological rehabilitation and physiotherapy after traumatic brain injury should observe neuroplasticity, motor learning, and motor control principles as well as taking a patient-centred approach with individual involvement in goals setting and choice of treatment procedures.

- Initial treatment during the acute phase focuses on promoting respiratory health and prevention of secondary adaptive changes to the musculoskeletal system.

- Subacute physiotherapy management focuses on the provision of an appropriate environment to assist functional recovery and on the assisted practice of meaningful tasks, relevant to the ability of the individual, using a full range of treatment modalities.

- Postacute physiotherapy management focuses on reversing secondary adaptive changes and improving specific motor skills with a focus on functional goals for the day to day activities and is dependent on skilled sensorimotor assessment and a collaborative approach with other team members, the individual, and family. This stage can include inpatient, outpatient, and community-based settings and for some individuals may require lifelong access to services including planned reviews.[13]

Summary[edit | edit source]

With the complexity of the traumatic brain injury and its wide-ranging consequences, no single medical speciality is sufficient to address all areas of management. In traumatic brain injury management, the role of the multidisciplinary team is invaluable with the physiotherapist/physical therapist role at its heart from acute to chronic stages.

The increasing recognition of the impact of traumatic brain injury on the individual, the family and society is resulting in developments in prevention, service design, legislation and funding. Developments in neuro-protective and neuro-restorative treatments and therapeutic approaches increase neuro-plastic change at cell and network levels. Access to more precise diagnostics is enabling more effective treatment choices. The expertise of specialist medical and rehabilitation centres is becoming more widely shared and implemented. We are living in truly exciting times when more than ever can be done for traumatic brain injury survivors.

Resources[edit | edit source]

BrainLine - An American multimedia website providing information and resources about treating and living with TBI; it includes a series of webcasts, written online resources and an electronic newsletter. It has a version in Spanish too.

Model Systems Knowledge Translation Centre (MSKTS) - The Model Systems Knowledge Translation Centre works closely with researchers in the 16 Traumatic Brain Injury Model Systems to develop resources for people living with traumatic brain injuries and their supporters. These evidence-based materials are available in a variety of formats such as printable PDF documents, videos, and slideshows.

Headway - A UK charity for TBI which has a comprehensive website, with information on the different aspects of TBI and its rehabilitation. It has a number of useful written resources for patients on the website, including ones on Brain Injury and Epilepsy, Loss of Taste and Smell after Brain Injury and Balance Problems and Dizziness after Brain Injury

References[edit | edit source]

- ↑ Zhang J, Zhang Y, Zou J, Cao F. A meta-analysis of cohort studies: Traumatic brain injury and risk of Alzheimer’s Disease. PLoS one. 2021 Jun 22;16(6):e0253206.

- ↑ Jacobson LA, Gerner G. Acquired brain injury: A developmental perspective.

- ↑ Menon DK, Schwab K, Wright DW, Maas AI. Demographics and Clinical Assessment Working Group of the International and Interagency Initiative toward Common Data Elements for Research on Traumatic Brain Injury and Psychological Health. Position statement: definition of traumatic brain injury. Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation. 2010;91(11):1637-40. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2010.05.017.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 Peeters W, van den Brande R, Polinder S, Brazinova A, Ewout W, Steyerberg EW, et al. Epidemiology of traumatic brain injury in Europe. Acta Neurochirurgica. 2015;157:1683–1696. DOI 10.1007/s00701-015-2512-7

- ↑ Shepard Centre. Understanding Traumatic Brain Injury. Available from: https://youtu.be/9Wl4-nNOGJ0[last accessed 30/08/19]

- ↑ Roozenbeek B, Andrew IR, Menon DK. Changing patterns in the epidemiology of traumatic brain injury. Nature Reviews Neurology. 2013; 9(4): 231-236

- ↑ Tjønndal A, Haudenhuyse R, de Geus B, Buyse L. Concussions, cuts and cracked bones: A systematic literature review on protective headgear and head injury prevention in Olympic boxing. European journal of sport science. 2021 Feb 16:1-3.

- ↑ Baker MS. Casualties of the Global War on Terror and their future impact on health care and society: a looming public health crisis. Military Medicine. 2014 Apr;179(4):348-55. doi: 10.7205/MILMED-D-13-00471.

- ↑ Traumatic brain injury in the United States: emergency department visits, hospitalizations, and deaths. Faul M, Xu L, Wald MM, Coronado VG. Atlanta (GA): Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Injury Prevention and Control; 2010

- ↑ Medical journal of Australia. Available from: Trends in severe traumatic brain injury in Victoria, 2006–2014 (accessed 15 May 2019)

- ↑ Corrigan JD, Selassie AW, Orman JA. The Epidemiology of Traumatic Brain Injury. The Journal Head Trauma Rehabilitation. 2010;25(2):72-80. doi: 10.1097/HTR.0b013e3181ccc8b4.

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 Vos PE, Alekseenko Y, Battistin L, Ehler E, Gerstenbrand F, Muresanu DF, et al. Mild traumatic brain injury. European Journal of Neurology. 2012; 19(2): 191-198.

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 13.2 Stokes M, Stack E, editors. Physical Management for Neurological Conditions E-Book. Third Edition. Elsevier Health Sciences; 2011 Apr 19.

- ↑ Brain Line. Living with a Traumatic Brain Injury. Available from: https://youtu.be/dyqGys9Htbo[last accessed 30/08/19]

- ↑ TEDx Talks. Follow the patient | Ben Clench | TEDxBrighton. Available from: https://youtu.be/2f1ueKZ8Rxc[last accessed 30/08/19]