Total Knee Arthroplasty

Original Editors - Lynn Wright

Top Contributors - Safiya Naz, Loes Verspecht, Kim Jackson, Lucinda hampton, Kun Man Li, Jess Bell, Ellen Wynant, Lisa Ingenito, Claire Knott, George Prudden, Karolien Van Melkebeke, Lynn Wright, Tarina van der Stockt, Lauren Lopez, Famke Coosemans, Leana Louw, 127.0.0.1, Evan Thomas, Ewa Jaraczewska, Greg Walding, Daniele Barilla, WikiSysop and Karen Wilson

Definition/Description[edit | edit source]

Total knee arthroplasty (TKA) or total knee replacement (TKR) is a common orthopaedic surgery that involves replacing the articular surfaces (femoral condyles and tibial plateau) of the knee joint with smooth metal and highly cross-linked polyethylene plastic.[1][2] TKA aims to improve the quality of life of individuals with end-stage osteoarthritis by reducing pain and increasing function[1], and was found to improve patients' sports and physical activity. [3] The number of TKA surgeries has increased in developed countries,[4] with younger patients receiving TKA.[5]

During surgery:

- There is at least one polyethylene piece, placed between the tibia and the femur as a shock absorber.[6]

- The prostheses are usually reinforced with cement, but may be left uncemented where bone growth is relied upon to reinforce the components.

- The patella may be replaced or resurfaced.[7][8] Patella reconstruction aims to restore the extensor mechanism.

- A quadriceps-splitting or quadriceps-sparing approach may be used. [9]

- The cruciate ligaments may be excised or preserved.

There are different types of surgical approaches, designs, and fixations.[6][10]

- A Unicondylar knee replacement[11] or Patellofemoral replacement (PFR) may also be performed depending on the extent of disease.[1]

- Several options of anaesthesia are available, and include regional anaesthesia in combination with local infiltration anaesthesia, or general anaesthesia in combination with local infiltration anaesthesia, with the possible addition of peripheral nerve blocks to either option.[12] A tourniquet may sometimes be used during surgery.[13]

- Computer-assisted navigation systems (CAS) or robotic surgery have been introduced in TKA surgery to facilitate surgeon hand motions in limited operating spaces (prospective studies on long term functional outcomes are needed).[14]It allows doctors to perform many types of complex procedures with more precision, flexibility and control than is possible with conventional techniques.CAS are usually associated with minimally invasive surgery (procedures performed through tiny incisions). It is also sometimes used in certain traditional open surgical procedures.[15][16]

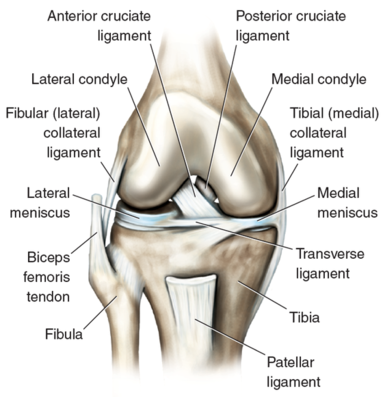

Clinically Relevant Anatomy[edit | edit source]

The Knee is a modified hinge joint that allows flexion and extension motions, with slight amounts of internal and external rotation. Three bones form the knee joint: the upper part of the tibia, the lower part of the femur and the patella. The articular surfaces are covered with a thin layer of cartilage. Meniscii adhere to the lateral and medial surfaces of the tibial plateau and aids in shock absorption. The knee joint is reinforced by ligaments and a joint capsule.

Epidemiology /Etiology[edit | edit source]

The most common indication for a primary knee replacement, TKA, is osteoarthritis.[1] Osteoarthritis causes the cartilage of the joint to become damaged and no longer able to absorb shock. Risk factors for knee osteoarthritis include gender, increased body mass index, history of a knee injury and comorbidities.[17][18] Pain is typically the main complaint of patients with knee osteoarthritis.[19] Pain is subjective, and involves peripheral and central neural mechanisms that are modulated by neurochemical, environmental, psychological and genetic factors.[19]

Total knee arthroplasty is more commonly performed on women and individuals of older ages.[6][20] In both the US and the UK, the majority of TKA surgeries were performed on women.[6][21] Dramatic increases in TKA surgeries are projected to occur[21] with an increasing rate of younger TKA recipients under the age of 60.[22]However according to Hawker et al[23], younger people undergoing TKA for knee osteoarthritis are more likely to have morbid obesity, they smoke, and their expected outcome is to return to vigorous activities, like sport. [23]

Diagnostic Procedures[edit | edit source]

Before a TKA surgery, a full medical evaluation is performed to determine risks and suitability. As part of this evaluation, imaging is used to assess the severity of joint degeneration and screen for other joint abnormalities.[24] A knee radiograph is performed to check for prosthetic alignment before the closure of the surgical incision.[8]

Pre-surgical Physiotherapy[edit | edit source]

Post-surgical rehabilitation exercises may be taught before surgery, so that patients may perform the appropriate exercises more effectively immediately after TKA surgery. A pre-surgical training programme may also be used to optimize the functional status of patients to improve post-surgical recovery. Pre-surgical training programmes should focus on postural control, functional lower limb exercises and strengthening exercises for bilateral lower extremities.[25]

Evidence supporting the efficacy of pre-surgical physiotherapy on patient outcome scores, lower limb strength, pain, range of movement or hospital length of stay following total knee arthroplasty is lacking.[26][27][28][29]

Post-TKA Surgery[edit | edit source]

A TKA surgery typically lasts 1 to 2 hours.[24] The majority of individuals begin physiotherapy during their inpatient stay, within 24 hours of surgery. Range of motion and strengthening exercises, cryotherapy and gait training are typically initiated, and a home exercise programme is prescribed before discharge from hospital. There is low-level evidence that accelerated physiotherapy regimens reduce the length of stay in an acute hospital.[30]

Patients are usually discharged after a few days’ stay in hospital and receive follow-up physiotherapy, in the outpatient or home care setting, within 1 week of discharge.[31]

The following post-operative guidelines for assessment and management are suggested for individuals who have undergone primary TKA surgery with cemented prosthesis, using a standard surgical approach. Surgeons’ instructions should always be followed.

Post-surgical Physiotherapy[edit | edit source]

Physiotherapy interventions are effective tools for improving patient's physical function, range of motion and pain in a short-term follow-up following total knee replacement. According to Fatoye and colleagues[32] long term benefit and cost-effectiveness of physiotherapy interventions after a total knee replacement needs further study. [32]

Subjective Assessment[edit | edit source]

Assessment should include, but is not limited to:

- Operative and post-operative complications, if any

- History of knee and other musculoskeletal complaints, if any

- Past medical history and relevant comorbidities

- Social factors and home set-up

- Progress of in-home exercises post-TKA surgery

- Pain and other symptoms/ discomfort (e.g. numbness, swelling)

- Expectations from surgery and rehabilitation

- Specific functional goals

Objective Assessment[edit | edit source]

In the objective assessment following Total Knee Arthroplasty (TKA), it is crucial to comprehensively evaluate various factors that contribute to the patient's recovery. It should include, but is not limited to:

- Observation of surgical wound or scar

- Check for signs of infection:

- Redness, discharge (pus/ odour), adhesions of the skin, abnormal warmth and swelling, expanding redness beyond the edges of the surgical incision, fever or chills

- Suspicion of infection warrants medical referral

- Knee swelling (circumference measurement)

- Vital signs and relevant laboratory findings (as relevant/in the acute setting)

- Check for deep vein thrombosis (DVT) (please see the Complications and Contraindications Section below for more information on identifying DVTs)

- Palpation:

- For increased warmth and swelling

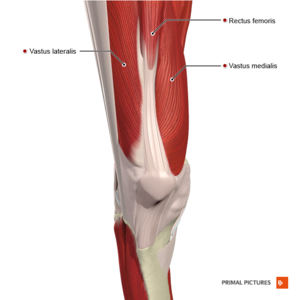

- Assessment of Muscle Function and Tone:

- For muscle activation (e.g. quadriceps; vastus medialis oblique).

- Assessing hypertonia, particularly in the hip adductors:

- Impact on Rehabilitation:

- Influences gait pattern and postural stability.

- May lead to altered gait, increasing stress on the knee joint.

- Essential to address for comprehensive rehabilitation.

- Impact on Rehabilitation:

- Lower limb range of motion:

- Active and passive knee range of motion in supine or semi-reclined position (see treatment milestones below for more details)

- Lower limb muscle activation and strength

- Gait:

- Timed up and go test (TUG) or 10-metre walk test may be used (depending on individuals’ ability and tolerance)

- Assess for guarding in knee flexion, avoidance to weight bear on the operative leg, antalgic patterns etc.

Outcome Measures[edit | edit source]

- Knee disability and Osteoarthritis Outcome score (KOOS)[33][34]

- Oxford Knee Score[34][35]

- Patient satisfaction[36]

- Walking tests: Timed up and go test (TUG), Six minute walking test[34]

- Visual Analogue Scale (VAS)

- Knee range of motion[34]

- Western Ontario and McMaster Universities Osteoarthritis Index score (WOMAC)[34][36]

Post-surgical Physiotherapy Treatment Strategies & Goals[edit | edit source]

Phase I: Up to 2-3 weeks post-surgery[31][37][edit | edit source]

- Patient education: pain science, pain management, the importance of home exercises, setting rehabilitation goals and expectations

- Achieve active and passive knee flexion to 90 degrees, and full knee extension

- Keep passive knee flexion range of motion testing to less than 90 degrees in the first 2 weeks to protect surgical incision and respect tissue healing

- Aim to achieve minimal pain and swelling

- Achieve full weight bearing

- Aim for independence in mobility and activities of daily living

During the early phase of rehabilitation, it is important to establish a therapeutic alliance and provide education on pain management strategies. Pain education may include appropriate usage of pain medication, cryotherapy[38] and elevation of the operated limb. There is evidence that cryotherapy improves knee range of motion and pain in the short-term. Icing after exercise may be helpful, but low quality evidence makes specific recommendations for the use of cryotherapy difficult.[39] Patients should be informed to avoid resting with a pillow under the knee as this may lead to contractures.

It is important to review the patient’s home exercise program during the first physiotherapy session as home exercises are a critical component of recovery. Post-surgical exercises given by the surgeon and inpatient physiotherapist should be reviewed. In the early phase, patients can be taught to use the stairs with their non-operated leg leading on the ascent, and their operated leg leading on the descent.

Common Bed and Chair Exercises[edit | edit source]

- Ankle plantarflexion/dorsiflexion

- Inner range quadriceps strengthening using a pillow or rolled towel behind the knee

- Isometric knee extension in the outer range

- Knee and hip flexion/extension

- Straight leg raises

- Isometric buttock contraction

- Hip abduction/adduction

- Bridging

Phase II: 4-6 weeks post-surgery[edit | edit source]

- Aim to have no quadriceps lag, with good, voluntary quadriceps muscle control

- Achieve 105 degrees active knee flexion range of motion

- Achieve full knee extension

- Aim for minimal to no pain and swelling

Physiotherapy sessions may be scheduled one to two times weekly, This frequency may increase or decrease depending on an individual's progress. Achieving full knee extension is essential for functional tasks such as walking and stair climbing. Knee flexion range of motion is required for comfortable walking (65 degrees), stair climbing (85 degrees), sitting and standing (95 degrees).[41] In this phase, tissue mobilisation techniques may be used to improve scar mobility.

Phase III: 6-8 weeks post-surgery[edit | edit source]

- Strengthening exercises to ensure hypertrophy beyond neural adaptation[31]

- Lower limb functional exercises

- Balance and proprioception training

While primary TKA has been reported to reduce falls incidence[42] and improve balance-related functions such as single limb standing balance,[42][43] the sub-optimal recovery of proprioception, sensory orientation, postural control, and strength of the operated limb post-TKA is well documented.[42][43][44] Literature highlights the importance of proprioceptive training, and pre-operative training[44] that involves the non-operated limb.[43] Balance exercises may include single leg balancing, stepping over objects, lateral step-ups, and standing on uneven surfaces. Post-surgical balance and proprioceptive training that involves single limb standing may begin when adequate knee control is achieved on the operated limb, which typically occurs around 8 weeks post-TKA.[31]

Individualised rehabilitation programmes that include strengthening and intensive functional exercises, given through land-based or aquatic programmes, may be progressed as clinical and strength milestones are met. Owing to the highly individualised characteristics of these exercises, supervision by a trained physiotherapist is beneficial.[45][46]

Phase IV: 8-12 weeks, up to 1 year post-surgery[edit | edit source]

- Aim for independent exercise in the community setting

- Continue regular exercise involving strengthening, balance and proprioception training

- Incorporate strategies for behaviour change to increase overall physical activity[47]

Discharge Criteria[edit | edit source]

Discharge planning should be individualised, and criteria may include:

- Achieving a minimum 110 degrees active knee flexion and full knee extension

- Achieving ambulation goals

- Achieving compliance and competency with a home exercise programme

- Commitment to an independent exercise program for 6-12 months post-operatively should be recommended

- Exercise programme should include strength training 2-3 times/ week

Complications and Contraindications[edit | edit source]

Following TKA surgery, these complications may occur:

- Infection

- Nerve damage

- Bone fracture (intra-operative or post-operative)

- Persistent / chronic pain[48][49]

- Increased Falls risk

- Deep vein thrombosis (DVT)

- A common complication after knee or hip replacement surgery that can cause significant morbidity and mortality

- Incidence of DVT after knee or hip replacement has been reported at 18%[50]

- Larger studies have reported that patients with hypercoagulable diagnosis / conditions are at greater risk of DVT within 6 months of joint replacement surgery[51]

- Identifying DVTs:

- Clinicians should be familiar with signs and symptoms of DVT such as chest pain, shortness of breath, skin redness or discolouration, warmth or increased skin temperature in the affected area, pain, tenderness, swelling (usually unilateral) and visible veins. However, please note that some patients with DVT could be asymptomatic.

- Please also note that Homan’s sign is a clinical test that has previously been used to assess for DVT. The patient is positioned in supine or semi-reclined, and the clinician passively dorsiflexes the ankle and squeezes the calf. However, Homan's sign is not considered a reliable test.[52]

- The Wells criteria and the Geneva score are two of the more commonly standardised clinical decision rules used to assess the pretest probability of DVT. The Wells score, in conjunction with the D-dimer test, has been validated.[53] You can find out more about the Wells criteria and Geneva score here: Advances in the diagnosis of venous thromboembolism: a literature review.[53]

- Suspicion of DVT warrants urgent medical referral. Definitive diagnosis typically requires D-dimer tests and ultrasound imaging (e.g. compression ultrasonography).[54]

- Stiffness[41]

- Most common complaint following primary TKA

- Affects approximately 6 to 7% of patients undergoing surgery[41]

- Contemporary literature supports defining “acquired idiopathic stiffness” as having a range of motion of <90° persisting for >12 weeks after primary TKA, in the absence of complicating factors including pre-existing stiffness.

- Stiffness causes significant functional disability and lower satisfaction[55]

- Females and obese patients are reported to have increased risk[56]

- Evidence does not recommend routine use of continuous passive motion (CPM) as long term clinical and functional effects are insignificant,[57][58] and not superior to traditional mobilisation techniques[59]

- Prosthesis-related complications: loosening or fracture of prosthesis components, joint instability and dislocation, component misalignment and breakdown

- While more research is needed for the long term failure rates of TKA implants, available arthroplasty registry data shows that 82% of TKA surgeries and 70% of unilateral knee replacement surgeries last 25 years in patients with osteoarthritis[1]

- Polyethylene wear is a common cause for revision surgery[1]

- High-risk activities that may not be permitted, or require clearance with the orthopaedic surgeon, post-surgery:

- Singles tennis, squash/racquet ball

- Jogging

- High impact aerobics

- Mountain biking

- Soccer, football, volleyball, baseball/softball, handball, basketball

- Gymnastics

- Water-skiing/ water sports

- Skiing

- Skating

References[edit | edit source]

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 1.5 Evans JT, Walker RW, Evans JP, Blom AW, Sayers A, Whitehouse MR. How long does a knee replacement last? A systematic review and meta-analysis of case series and national registry reports with more than 15 years of follow-up. The Lancet. 2019 Feb 16;393(10172):655-63.

- ↑ Palmer, S., 2020. Total Knee Arthroplasty (TKA). [online] Medscape. Available at: <https://emedicine.medscape.com/article/1250275-overview#:~:text=The%20primary%20indication%20for%20total,pain%20caused%20by%20severe%20arthritis.> [Accessed 22 December 2020].

- ↑ Meena A, Hoser C, Abermann E, Hepperger C, Raj A, Fink C. Total knee arthroplasty improves sports activity and the patient-reported functional outcome at mid-term follow-up. Knee Surgery, Sports Traumatology, Arthroscopy. 2022 Jun 11:1-9.

- ↑ Jakobsen TL, Jakobsen MD, Andersen LL, Husted H, Kehlet H, Bandholm T. Quadriceps muscle activity during commonly used strength training exercises shortly after total knee arthroplasty: implications for home-based exercise-selection. Journal of experimental orthopaedics. 2019 Dec 1;6(1):29.

- ↑ Scott CE, Oliver WM, MacDonald D, Wade FA, Moran M, Breusch SJ. Predicting dissatisfaction following total knee arthroplasty in patients under 55 years of age. The bone & joint journal. 2016 Dec;98(12):1625-34.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 6.3 Medscape. Total knee arthroplasty (TKA). Available from: https://emedicine.medscape.com/article/1250275-overview#:~:text=The%20primary%20indication%20for%20total,pain%20caused%20by%20severe%20arthritis. (accessed 28/07/2020).

- ↑ Maney AJ, Koh CK, Frampton CM, Young SW. Usually, selectively, or rarely resurfacing the patella during primary total knee arthroplasty: determining the best strategy. JBJS. 2019 Mar 6;101(5):412-20.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 Nucleus Medicine Media. Total Knee replacement surgery. Available from: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=EV6a995pyYk [Accessed 22 December 2020]

- ↑ Berstock JR, Murray JR, Whitehouse MR, Blom AW, Beswick AD. Medial subvastus versus the medial parapatellar approach for total knee replacement: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. EFORT open reviews. 2018 Mar;3(3):78-84.

- ↑ Parcells BW, Tria AJ. The cruciate ligaments in total knee arthroplasty. American Journal of Orthopaedics (Belle Mead NJ), 45(4), pp. E153-60. 2016;45(4):153-60.

- ↑ Physiopedia. 2020. Partial Knee Replacement. [online] Available at: <https://physio-pedia.com/Partial_Knee_Replacement?utm_source=physiopedia&utm_medium=search&utm_campaign=ongoing_internal> [Accessed 22 December 2020].

- ↑ 2020. Guideline - Joint Replacement (Primary): Hip, Knee And Shoulder. [ebook] NATIONAL INSTITUTE FOR HEALTH AND CARE 2 EXCELLENCE, p.5. Available at: <https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng157/documents/draft-guideline> [Accessed 22 December 2020].

- ↑ Fan Y, Jin J, Sun Z, Li W, Lin J, Weng X, Qiu G. The limited use of a tourniquet during total knee arthroplasty: a randomized controlled trial. Knee. 2014; 21(6): 1263-1268

- ↑ Panjwani TR, Mullaji A, Doshi K, Thakur H. Comparison of functional outcomes of computer-assisted vs conventional total knee arthroplasty: a systematic review and meta-analysis of high-quality, prospective studies. The Journal of arthroplasty. 2019 Mar 1;34(3):586-93.

- ↑ Moten SC, Kypson AP, Chitwood Jr WR. Use of robotics in other surgical specialties. InRobotics in Urologic Surgery 2008 Jan 1 (pp. 159-173). WB Saunders.Available from:https://www.sciencedirect.com/topics/medicine-and-dentistry/computer-assisted-surgery (accessed 17.2.2021)

- ↑ Robotic surgery Mayo clinic Available from:https://www.mayoclinic.org/tests-procedures/robotic-surgery/about/pac-20394974 (accessed 17.2.2021)

- ↑ Blagojevic, M., Jinks, C., Jeffery, A. and Jordan, K. Risk factors for onset of osteoarthritis of the knee in older adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Osteoarthritis and Cartilage. 2010;18(1):24-33.

- ↑ Driban J, McAlindon T, Amin M, Price L, Eaton C, Davis J et al. Risk factors can classify individuals who develop accelerated knee osteoarthritis: Data from the osteoarthritis initiative. Journal of Orthopaedic Research. 2017;36(3):876-880.

- ↑ 19.0 19.1 Fu K, Robbins S, McDougall J. Osteoarthritis: the genesis of pain. Rheumatology. 2017;57(suppl_4):iv43-iv50.

- ↑ Knee Replacement Surgery By The Numbers - The Center [Internet]. The Center Orthopedic and Neurosurgical Care & Research. 2020 [cited 22 December 2020]. Available from: https://www.thecenteroregon.com/medical-blog/knee-replacement-surgery-by-the-numbers/

- ↑ 21.0 21.1 Singh J, Yu S, Chen L, Cleveland J. Rates of Total Joint Replacement in the United States: Future Projections to 2020–2040 Using the National Inpatient Sample. The Journal of Rheumatology. 2019;46(9):1134-1140.

- ↑ Ravi B, Croxford R, Reichmann W, Losina E, Katz J, Hawker G. The changing demographics of total joint arthroplasty recipients in the United States and Ontario from 2001 to 2007. Best Practice & Research Clinical Rheumatology. 2012;26(5):637-647.

- ↑ 23.0 23.1 Hawker GA, Bohm E, Dunbar MJ, Jones CA, Noseworthy T. The Effect of Patient Age and Surgical Appropriateness and Their Influence on Surgeon Recommendations for Primary TKA: A Cross-Sectional Study of 2,037 Patients. JBJS. 2022 Apr 20;104(8):700-8.

- ↑ 24.0 24.1 Foran J. Total Knee Replacement - OrthoInfo - AAOS [Internet]. Orthoinfo. 2020 [cited 22 December 2020]. Available from: https://orthoinfo.aaos.org/en/treatment/total-knee-replacement/

- ↑ Huber E, de Bie R, Roos E, Bischoff-Ferrari H. Effect of pre-operative neuromuscular training on functional outcome after total knee replacement: a randomized-controlled trial. BMC Musculoskeletal Disorders. 2013;14(1).

- ↑ Kwok I, Paton B, Haddad F. Does Pre-Operative Physiotherapy Improve Outcomes in Primary Total Knee Arthroplasty? — A Systematic Review. The Journal of Arthroplasty. 2015;30(9):1657-1663.

- ↑ Alghadir A, Iqbal Z, Anwer S. Comparison of the effect of pre- and post-operative physical therapy versus post-operative physical therapy alone on pain and recovery of function after total knee arthroplasty. Journal of Physical Therapy Science. 2016;28(10):2754-2758.

- ↑ Husted R, Juhl C, Troelsen A, Thorborg K, Kallemose T, Rathleff M et al. The relationship between prescribed pre-operative knee-extensor exercise dosage and effect on knee-extensor strength prior to and following total knee arthroplasty: a systematic review and meta-regression analysis of randomized controlled trials. Osteoarthritis and Cartilage. 2020;28(11):1412-1426.

- ↑ Chesham R, Shanmugam S. Does preoperative physiotherapy improve postoperative, patient-based outcomes in older adults who have undergone total knee arthroplasty? A systematic review. Physiotherapy Theory and Practice. 2016;33(1):9-30.

- ↑ Henderson K, Wallis J, Snowdon D. Active physiotherapy interventions following total knee arthroplasty in the hospital and inpatient rehabilitation settings: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Physiotherapy. 2018;104(1):25-35.

- ↑ 31.0 31.1 31.2 31.3 McHugh, A, Rehabilitation Guidelines Following Total Knee Arthroplasty. Plus. 2021.

- ↑ 32.0 32.1 Fatoye F, Yeowell G, Wright JM, Gebrye T. Clinical and cost-effectiveness of physiotherapy interventions following total knee replacement: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Archives of Orthopaedic and Trauma Surgery. 2021 Oct;141(10):1761-78.

- ↑ Gauthier-Kwan O, Dobransky J, Dervin G. Quality of Recovery, Postdischarge Hospital Utilization, and 2-Year Functional Outcomes After an Outpatient Total Knee Arthroplasty Program. The Journal of Arthroplasty. 2018;33(7):2159-2164.e1.

- ↑ 34.0 34.1 34.2 34.3 34.4 Artz N, Elvers K, Lowe C, Sackley C, Jepson P, Beswick A. Effectiveness of physiotherapy exercise following total knee replacement: systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Musculoskeletal Disorders. 2015;16(1).

- ↑ Jiang Y, Sanchez-Santos M, Judge A, Murray D, Arden N. Predictors of Patient-Reported Pain and Functional Outcomes Over 10 Years After Primary Total Knee Arthroplasty: A Prospective Cohort Study. The Journal of Arthroplasty. 2017;32(1):92-100.e2.

- ↑ 36.0 36.1 Bourne R. Measuring Tools for Functional Outcomes in Total Knee Arthroplasty. Clinical Orthopaedics and Related Research. 2008;466(11):2634-2638.

- ↑ Meier W, Mizner R, Marcus R, Dibble L, Peters C, Lastayo P. Total Knee Arthroplasty: Muscle Impairments, Functional Limitations, and Recommended Rehabilitation Approaches. Journal of Orthopaedic & Sports Physical Therapy. 2008;38(5):246-256.

- ↑ Bech M, Moorhen J, Cho M, Lavergne M, Stothers K, Hoens A. Device or Ice: The Effect of Consistent Cooling Using a Device Compared with Intermittent Cooling Using an Ice Bag after Total Knee Arthroplasty. Physiotherapy Canada. 2015;67(1):48-55.

- ↑ Adie S, Kwan A, Naylor J, Harris I, Mittal R. Cryotherapy following total knee replacement. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2012.

- ↑ UnityPoint Health - Cedar Rapids. Knee replacement exercise video for UnityPoint Health - St. Luke's Hospital patients [Internet]. 2020 [cited 22 December 2020]. Available from: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=nM0K5MlQc3U

- ↑ 41.0 41.1 41.2 González Della Valle A, Leali A, Haas S. Etiology and Surgical Interventions for Stiff Total Knee Replacements. HSS Journal. 2007;3(2):182-189.

- ↑ 42.0 42.1 42.2 Si H, Zeng Y, Zhong J, Zhou Z, Lu Y, Cheng J et al. The effect of primary total knee arthroplasty on the incidence of falls and balance-related functions in patients with osteoarthritis. Scientific Reports. 2017;7(1).

- ↑ 43.0 43.1 43.2 Moutzouri M, Gleeson N, Billis E, Tsepis E, Panoutsopoulou I, Gliatis J. The effect of total knee arthroplasty on patients’ balance and incidence of falls: a systematic review. Knee Surgery, Sports Traumatology, Arthroscopy. 2016;25(11):3439-3451.

- ↑ 44.0 44.1 Chan A, Jehu D, Pang M. Falls After Total Knee Arthroplasty: Frequency, Circumstances, and Associated Factors—A Prospective Cohort Study. Physical Therapy. 2018;98(9):767-778.

- ↑ Husby VS, Foss OA, Husby OS, Winther SB. Randomized controlled trial of maximal strength training vs. standard rehabilitation following total knee arthroplasty. European Journal of Physical and Rehabilitation Medicine. 2017;54(3):371-379

- ↑ Schache M, McClelland J, Webster K. Lower limb strength following total knee arthroplasty: A systematic review. The Knee. 2014;21(1):12-20.

- ↑ Arnold J, Walters J, Ferrar K. Does Physical Activity Increase After Total Hip or Knee Arthroplasty for Osteoarthritis? A Systematic Review. Journal of Orthopaedic & Sports Physical Therapy. 2016;46(6):431-442.

- ↑ Hasegawa M, Tone S, Naito Y, Wakabayashi H, Sudo A. Prevalence of Persistent Pain after Total Knee Arthroplasty and the Impact of Neuropathic Pain. The Journal of Knee Surgery. 2018;32(10):1020-1023.

- ↑ Kim M, Koh I, Sohn S, Kang B, Kwak D, In Y. Central Sensitization Is a Risk Factor for Persistent Postoperative Pain and Dissatisfaction in Patients Undergoing Revision Total Knee Arthroplasty. The Journal of Arthroplasty. 2019;34(8):1740-1748.

- ↑ Zhang H, Mao P, Wang C, Chen D, Xu Z, Shi D et al. Incidence and risk factors of deep vein thrombosis (DVT) after total hip or knee arthroplasty. Blood Coagulation & Fibrinolysis. 2016;28(2):126-133(8).

- ↑ Bawa H, Weick J, Dirschl D, Luu H. Trends in Deep Vein Thrombosis Prophylaxis and Deep Vein Thrombosis Rates After Total Hip and Knee Arthroplasty. Journal of the American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons. 2018;26(19):698-705.

- ↑ Thanavaro J. Diagnosis of venous thromboembolism using clinical pretest probability rules, D-dimer assays, and imaging techniques. Nurse Pract. 2021 May 1;46(5):15-22.

- ↑ 53.0 53.1 Patel H, Sun H, Hussain AN, Vakde T. Advances in the diagnosis of venous thromboembolism: a literature review. Diagnostics (Basel). 2020 Jun 2;10(6):365.

- ↑ Kearon C, de Wit K, Parpia S, Schulman S, Spencer FA, Sharma S, et al. Diagnosis of deep vein thrombosis with D-dimer adjusted to clinical probability: prospective diagnostic management study. BMJ. 2022 Feb 15;376:e067378.

- ↑ Clement N, Bardgett M, Weir D, Holland J, Deehan D. Increased symptoms of stiffness 1 year after total knee arthroplasty are associated with a worse functional outcome and lower rate of patient satisfaction. Knee Surgery, Sports Traumatology, Arthroscopy. 2018;27(4):1196-1203.

- ↑ Tibbo M, Limberg A, Salib C, Ahmed A, van Wijnen A, Berry D et al. Acquired Idiopathic Stiffness After Total Knee Arthroplasty. The Journal of Bone and Joint Surgery. 2019;101(14):1320-1330.

- ↑ Wirries N, Ezechieli M, Stimpel K, Skutek M. Impact of continuous passive motion on rehabilitation following total knee arthroplasty. Physiotherapy Research International. 2020;25(4).

- ↑ Mayer M, Naylor J, Harris I, Badge H, Adie S, Mills K et al. Evidence base and practice variation in acute care processes for knee and hip arthroplasty surgeries. PLOS ONE. 2017;12(7):e0180090.

- ↑ Trzeciak T, Richter M, Ruszkowski K. Efektywność ciagłego biernego ruchu po zabiegu pierwotnej endoprotezoplastyki stawu kolanowego [Effectiveness of continuous passive motion after total knee replacement]. Chirurgia Narzadów Ruchu i Ortopedia Polska. 2011;76(6):345-9.