Rehabilitation Frameworks

Original Editors - Naomi O'Reilly and ReLAB-HS

Top Contributors - Naomi O'Reilly, Cindy John-Chu, Kim Jackson, Chelsea Mclene, Vidya Acharya, Rucha Gadgil, Oyemi Sillo, Tarina van der Stockt, Lucinda hampton and Ashmita Patrao

Introduction[edit | edit source]

Rehabilitation is a goal-oriented process that enables individuals with impairments, activity limitations and participation restrictions to identify and reach their optimal physical, mental and social functional level through a patient-focused partnership with family, rehabilitation providers and the community. Rehabilitation focuses on optimising function and aims to facilitate independence and social integration. It includes prevention of injury/illness recurrence and/or secondary conditions.

Rehabilitation Frameworks provide guidance to support clinicians, managers and planners to improve access to quality, sustainable rehabilitation services. These frameworks outline the key elements foundational to rehabilitation services and promote a shared understanding of rehabilitation through the provision of a common language and definitions for concepts relevant to rehabilitation. This serves as a guide for planning, managing and delivering consistent and preferred rehabilitation approaches to meet patient and community needs.

There is a wide range of frameworks available that underpin rehabilitation services within different contexts, which include but are not limited to Competency Frameworks, Standards of Practice, Models of Care and Integrated Care Pathways. A common rehabilitation language is vital because people with impaired functioning may interact with many professionals and systems, for example, health, education and social care. Rehabilitation processes are more efficient if all those involved are basing their approaches and communication on a common language and concepts. This is particularly the case now that some health and human services and systems provide long term services and support for the growing number of people affected by chronic conditions. A common language is essential to support integrated care, ensure person-centred care and is foundational to rehabilitation frameworks.

Common Language[edit | edit source]

The International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health (ICF), introduced by the World Health Organization (WHO) in 2001, provides a common language in order to ensure a comprehensive understanding and description of ‘functioning’ and should provide the foundation to all rehabilitation frameworks.[1][2]It utilises a biopsychosocial approach to health that is patient-centred and recognises the many factors that influence health and optimal function. The model encourages rehabilitation providers to look at how health conditions interact with contextual factors, both internal and external to the individual, to impact the individual’s daily activities and participation in society.[3] Adopting this model as the foundation to rehabilitation frameworks will support rehabilitation providers, researchers and administrators to shift their practice to focus more on optimising function and provide guidance for planning and evaluating rehabilitation service. [4][5]

With the use of this common language, all disciplines within rehabilitation can have a greater understanding of what each other does and begin to form commonalities across discipline-specific models of thinking to enable a more scientific discourse to examine and determine the nature of functioning, both as a whole or in its component parts. This allows for investigation into the connections between its component parts, the determinants of functioning and the effectiveness of interventions that might improve functioning. As such the ICF should be a central pillar of rehabilitation theory and practice and underpin all of the following rehabilitation frameworks.[5]

Rehabilitation in Health Framework[edit | edit source]

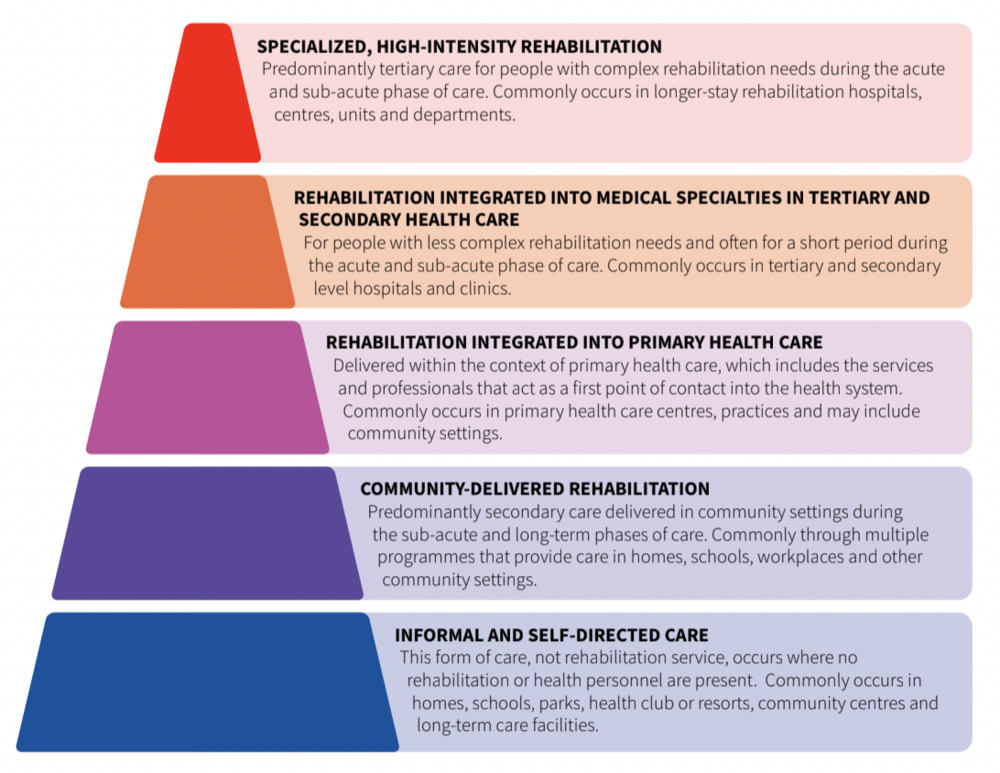

The Rehabilitation in Health Framework (Figure 1) provides a common structure and organisation of rehabilitation within health care, which can be utilised in the development of rehabilitation services to help inform the systematic assessment of rehabilitation situations within a specific context. Across countries, there is significant variation in the configuration of rehabilitation but this framework highlights the common types of rehabilitation and suggests an optimal mix of rehabilitation in a country. It also highlights the different types of rehabilitation and the settings where rehabilitation most commonly occurs. Visualised through an adapted pyramidal structure, which is commonly used to illustrate the organisation of tertiary, secondary and primary health care with the addition of community-delivered rehabilitation and informal self-care as the key elements forming the base of this model.[6]

| Types of Rehabilitation | Characteristics | User Groups |

|---|---|---|

| Specialised, High-Intensity Rehabilitation |

|

|

| Rehabilitation Integrated into

Medical Specialties in Tertiary and Secondary Health Care |

|

|

| Rehabilitation Integrated into

Primary Health Care |

|

|

| Community-

Delivered Rehabilitation |

|

|

| Informal

and Self-Directed Care |

|

This includes anyone who initiates activities to maintain or further improve their functioning. |

Competency Frameworks[edit | edit source]

Competency in a professional capacity is “the behavioural definition of the knowledge, skills, values and personal qualities that underlie the adequate performance of professional activities”[7], and is a dynamic process that requires the healthcare professional to ‘keep abreast with change’ in order to maintain and continually develop competencies[8]. Competence should be linked to the measurable, durable, and trainable behaviours that contribute to the performance of activities, demonstrating whether a person is competent or able to perform activities to a defined standard. Activities are groups of time-limited, trainable and measurable tasks that draw on knowledge, skills, values and attitudes[9]. Furthermore, competence is the ability of a healthcare professional to practice safely and effectively in a range of contexts and situations of varying levels of complexity. The level of an individual's competence in any situation will be influenced by many factors which include, but are not limited to their qualifications, clinical experience, professional development, and ability to integrate knowledge, skills, attitudes, values, and judgements.[10][11].

A competency framework is a structure that sets out and defines each individual competency or personal attribute (such as problem-solving or people management) required by individuals working in an organisation or part of that organisation. It is an effective model that broadly describes performance excellence. Such a framework usually includes a number of competencies that are applied to multiple roles within an organisation, with each competency defining, in generic terms, excellence in working behaviour. A competency framework is a means by which organisations can communicate which behaviours are required, valued, recognised and rewarded with respect to specific occupational roles. It ensures a common understanding of the organization’s values and expected excellent performance behaviours.

Competency frameworks are used throughout a wide range of systems globally (for example; Health Systems, Education Systems, Businesses), and serve a range of purposes. Historically in healthcare, they emerged with two distinct aims, each with specific characteristics: [9] to support the development of capabilities (generally the primary concern of the education sector training healthcare professionals), and to help define standards of performance (generally the primary concern of the healthcare system to guide performance expectations in the workplace). Although in practice many competency frameworks achieve a hybrid of the above two aims and have key characteristics dependent on the context for which the competency framework is being used. Below we look at the key characteristics of competency frameworks within the main applications in which they are currently utilised (Table.2).

| Application | Key Characteristics of Competency Frameworks |

|---|---|

| Supporting rehabilitation education and training such as guiding curriculum development. | Education institutions use competency frameworks for articulating the outcomes of their courses. They can be used to shape the learning outcomes of courses, and to ensure that the knowledge and skills taught by the institution are aligned with population needs.

|

| Supporting professional regulation, accreditation or licensing for rehabilitation. | Regulatory or accreditation bodies use competency frameworks to communicate the standards expected of a profession. When applied to pre-and post-service education and enforced through audits and other mechanisms, they form an integral component of the quality assurance process.

|

| Supporting performance appraisal of rehabilitation workforce. | In the context of human resource management, competency frameworks define performance excellence and provide a benchmark against which workers are assessed. They are also integral to establishing individual and service-wide development priorities.

|

| Supporting Ministries of Health and specific health services in workforce evaluation and planning. | In the context of planning, they enable services to successfully align their staff competencies and activities with population needs and service objectives and help to identify knowledge and skill gaps and performance deficiencies. Ministries of health can apply competency frameworks in workforce evaluation and planning, such as in conduct competency gap analyses. |

Within the health care systems, most individuals within the workforce are initially guided by a Competency Framework developed through their specific professional body, which focuses on discipline-specific competencies. But more recently the World Health Organisation, recognising the need for a competency framework that can be ‘adopted and adapted’ by any rehabilitation professional group or specialisation and for any setting, have developed the Rehabilitation Competency Framework. Below we will look at these competency frameworks in a bit more detail.

Professional Organisation Competency[edit | edit source]

There are many core professions that offer rehabilitation services including but not limited to: audiology, occupational therapy, physical and rehabilitation medicine, physiotherapy, prosthetics and orthotics, psychology, rehabilitation nursing and speech and language therapy. Aiming to provide “interventions designed to optimize functioning and reduce disability in individuals with health conditions in interaction with their environment”[13], with potential to improve an individual’s functioning and their ability to successfully and optimally interact with their environment[14]. Most of these core rehabilitation professions have developed their own national and/or international competency frameworks or guidelines that communicate professional standards, support education, guide curriculum planning and development for entry-level healthcare professionals within a specific discipline and help to establish individual and service-wide development priorities forming an integral component of quality assurance when enforced through audits and other mechanisms[15].

| Professional Organisation | Competency Framework |

|---|---|

| Audiology | Canadian Alliance of Audiology and Speech-Language Pathology Regulators |

| Occupational Therapy | World Federation of Occupational Therapists (WFOT). |

| Physical and Rehabilitation Medicine | International Society of Physical and Rehabilitation Medicine (ISPRM) |

| Physiotherapy | World Physiotherapy |

| Prosthetics and Orthotics | International Society of Prosthetics and Orthotics (ISPO) |

| Psychology | International Association of Applied Psychology (IAAP) and International Union of Psychological Science (IUPsyS) |

| Rehabilitation Nursing | Association of Rehabilitation Nurses (ARN) |

| Speech and Language Therapy | Canadian Alliance of Audiology and Speech-Language Pathology Regulators |

WHO Rehabilitation Competency Frameworks[edit | edit source]

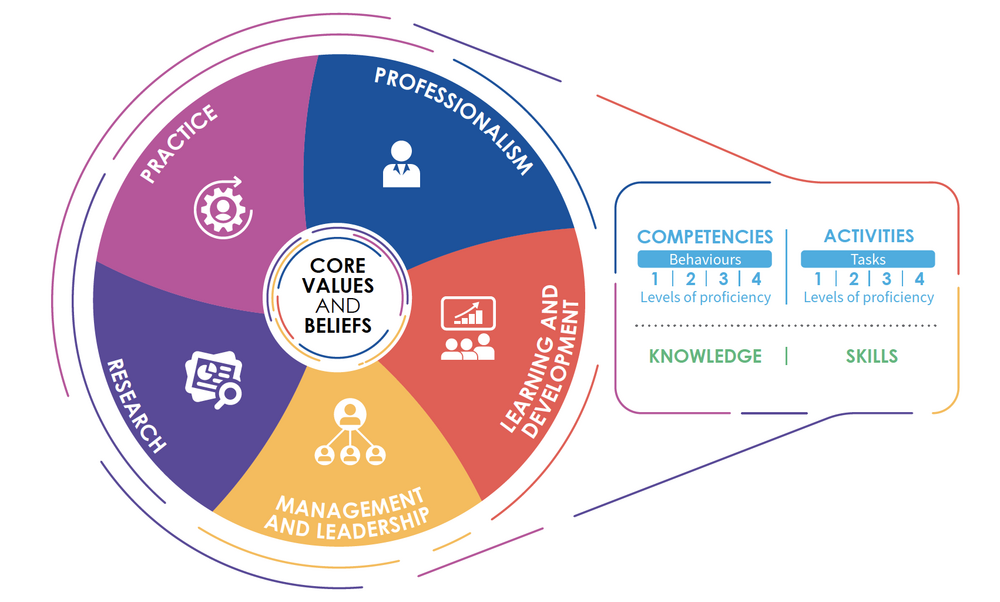

Until recently, a competency framework relevant to both low and high resource settings that complements rehabilitation competencies across all health and social care disciplines did not exist. Therefore, the World Health Organisation (WHO) took on the task of creating a resource to help strengthen the rehabilitation workforce identity and released the Rehabilitation Competency Framework (RCF) at the beginning of 2021[15][16]. The RCF captures what people delivering or supporting rehabilitation do (activities), and the behaviours, knowledge and skills (competencies) that enable quality care and service delivery. It incorporates activities and competencies across the areas of rehabilitation practice, professionalism, learning and development, management and leadership, and research. It is a model that communicates the expected or aspired performance of the rehabilitation workforce across different countries and settings to enable quality care and service delivery. The model comprises of five domains centred around core values and beliefs, which sit at the heart of the framework and help shape the behaviour of a rehabilitation worker and their performance of tasks across all the RCF domains.

It is relevant to all rehabilitation disciplines, specialisations and settings. The core values, beliefs and competencies, as well as the behaviours through which these are expressed can be considered cross-cutting and applicable to all rehabilitation workers at all levels of rehabilitation. The activities, and the tasks that they encompass, capture the range of rehabilitation work and not all will be relevant to every rehabilitation worker. In the process of contextualizing the RCF, competency framework developers are expected to extract only the activities and tasks relevant to their specific workforce.[12] Likewise the values and beliefs may be interpreted slightly differently by different people and cultures and thus may be adapted somewhat into a context-specific competency framework.

The Four Core Values are:

- Compassion and empathy

- Sensitivity & respect for diversity

- Dignity & human rights

- Self-determination.

The Four Core Beliefs are that rehabilitation should be:

- Person centred

- Collaborative

- Available to anyone who needs it and

- Functioning is central to health.

The Five Domains are:

- Practice

- Professionalism

- Learning and Development

- Management and Leadership

- Research

The domains collectively capture how the rehabilitation workforce behave in order to perform effectively (competencies), and what they do (activities). The RCF defines competency as an “observable ability of a person, integrating knowledge, skills, values and beliefs in their performance of tasks[18]. Competencies are durable, trainable and, through the expression of behaviours, measurable” (WHO 2020 p. vii). Where an activity is “an area of work that encompasses groups of related tasks. Activities are time-limited, trainable and, through the performance of tasks, measurable.” (WHO 2020 p. vii). The RCF breaks down their competencies and activities even further by explaining practice knowledge (core knowledge and activity-specific knowledge) and practice skills (core skills and activity-specific skills) within each domain. Competencies are broken down into behaviours; and activities into tasks. Each is described across four levels of proficiency. Each domain also describes the knowledge and skills that underpin the activities and competencies. These include core knowledge and skills, as well as those that are specific to an activity.

| Competency | Activity |

|---|---|

| Associated with a rehabilitation worker | Associated with a role, its requirements and the scope of practice of the specific rehabilitation worker |

| Durable (persist through different activities) | Begin and End |

| Expressed as Behaviours | Encompass Tasks |

| Relevant to all rehabilitation workers | Relevant to some rehabilitation workers and not others, depending on their role |

The RCF is a model that can be used as a tool to provide guidance across the rehabilitation workforce to facilitate quality care of service delivery [19]. It can be used as a reference to develop competency frameworks for specific contexts and has been designed to be easily adapted by any rehabilitation profession, setting or specialization. It also provides a structure, language and menu of core and optional content relevant to those who will use it and what it will be used for. The Rehabilitation Competency Framework does not replace or supersede existing national or international competency frameworks or standards. Rather, professional associations and regulatory bodies can refer to the Rehabilitation Competency Framework when developing or revising their own competency frameworks or standards if they want to align the language, concepts and structure, to improve communication and comparability between professions and countries.

Standards of Practice[edit | edit source]

According to the American Psychological Association Dictionary of Psychology, Standards of Practice is defined as

"a set of guidelines that delineate the expected techniques and procedures, and the order in which to use them, for interventions with individuals experiencing a range of ... conditions.

Standards of practice are the “how-to” of the discipline or clinical specialty in that they describe more specifically what is and is not considered to be good practice in a given discipline. The primary reason for having standards is to promote, guide, direct and regulate the professional practice. Standards of practice can include clinical policy statements, standards of practice, standard operating procedures, clinical practice protocols, and clinical procedures. Standards set out the legal and professional requirements for rehabilitation practice and describe the level of performance expected of rehabilitation professionals in their practice. Standards guide the professional knowledge, skills, values and judgments needed for safe practice for rehabilitation professionals, regardless of role and the setting in which they may practise.

Standards of Practice have been developed by many professional organisations to ensure that practitioners use the most well researched and validated treatment plans available in their fields. Effectively they support the clinician, the management team, and the healthcare organisation to develop safe staffing practices, delegate tasks to licensed and unlicensed personnel, ensure adequate documentation and even create policies for new technology such as social media.

Standards of practice guarantee that we are accountable for our clinical decisions and actions, and for maintaining competence during our career. They are patient-centred, promote the best possible outcome, and minimize exposure to the risk of harm. These standards encourage us to persistently enhance our knowledge base through experience, continuing education, and the latest guidelines. We can utilize standards of practice to identify areas for improvement in our clinical practice, work areas, as well as to improve patient and workplace safety. [20]

| Professional Organisation | Competency Framework |

|---|---|

| Audiology | American Academy of Audiology |

| Occupational Therapy | World Federation of Occupational Therapists (WFOT) |

| Physiotherapy | World Physiotherapy |

| Prosthetics and Orthotics | World Health Organisation |

| Psychology | British Psychological Association |

| Rehabilitation Nursing | Association of Rehabilitation Nurses (ARN) |

| Speech and Language Therapy | Speech Pathology Australia |

| Assistive Technology | Rehabilitation Engineering and Assistive Technology Society of North America (RESNA) |

| Paediatrics | World Health Organisation |

Models of Care[edit | edit source]

A “Model of Care” broadly defines the way health services are delivered. It outlines best practice care and services for a person, population group or patient cohort as they progress through the stages of a condition, injury or event. It aims to ensure people get the right care, at the right time, by the right team and in the right place[21]. Models of Care often have their origins in care management for chronic conditions. These models share many components because they seek to address the multiple determinants of health that are common across conditions.

The Chronic Care Model, is an organizational approach to caring for people with chronic disease in a primary care setting, and provides an excellent framework to understand the rationale for the common components across models of care. The system is population-based and creates practical, supportive, evidence-based interactions between an informed, activated patient and a prepared, proactive practice team.

Integrated Care Pathways[edit | edit source]

Integrated care pathways (ICPs) are a pre-defined framework of evidence based, multidisciplinary practice for specific patients. They have the potential to enhance continuity of care, patient safety, patient satisfaction, efficiency gains, teamwork and staff education. It provides an outline of anticipated care, placed in an appropriate timeframe, to help a patient with a specific condition or set of symptoms move progressively through a clinical experience to positive outcomes. While variations from the pathway may occur as clinical freedom is exercised to meet the needs of the individual patient, ICPs can help to reduce unnecessary variations in patient care and outcomes. [22][23] They support the development of care partnerships and empower patients and their carers. ICPs can also be used as a tool to incorporate local and national guidelines into everyday practice, manage clinical risk and meet the requirements of clinical governance. The ICP for patients with spinal cord injuries spans numerous service delivery sites, beginning at the time of initial presentation through to long term management in an appropriate setting. The ICP will include reference to the breadth of the patient journey and address issues that include Pre-hospital care, Reception & Intervention, Reconstruction & Ongoing care (including acute rehabilitation), Post-Acute Rehabilitation and Life-long care.

Integrated care pathways are important because they help to reduce unnecessary variations in patient care and outcomes. They support the development of care partnerships and empower patients and their carers. Also, they can be used as a tool to incorporate local and national guidelines into everyday practice, manage clinical risk, and meet the requirements of clinical governance. When designing and introducing integrated care pathways, it is important to incorporate them into organisational strategies and choose appropriate topics that provide opportunities for improvement.

The integrated care pathway should be able to address the following issues;

- Who does what?

- Where was it done?

- When is it done?

- How much does it cost?

- Why was it not done?

- What was the valued outcome?

Resources[edit | edit source]

Competency Frameworks[edit | edit source]

- What is Competence? [24]

- Towards a Global Competency Framework [25]

- Proposing a Re-conceptualisation of Competency Framework Terminology for Health: A Scoping Review

Models of Care[edit | edit source]

Examples

- Models of Care for the Diabetic Foot

- Models of Care Delivery from Rehabilitation to Community for Spinal Cord Injury

Integrated Care Pathways[edit | edit source]

- Integrated Care Pathways: Eleven International Trends

- Improving the Patient Journey: Understanding Integrated Care Teams

Examples

- Integrated Care Pathways in Neurosurgery: A Systematic Review

- Integrated Care Pathway for the Management of Spinal Cord Injury

- British Society for Paediatric Endocrinology & Diabetes Integrated Care Pathway for Children and Young People (aged 0-18 years) with Diabetic Ketoacidosis

References [edit | edit source]

- ↑ Ustun, T. B., Chatterji, S., Bickenbach, J., Kostanjsek, N. and Schneider, M. (2003). The International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health: a new tool for understanding disability and health. Disability and Rehabilitation, 25(11–12), 565–571.

- ↑ Sykes C. Health classifications 1 - An introduction to the ICF. WCPT Keynotes. World Confederation for Physical Therapy. 2006.

- ↑ Rauch A, Cieza A, Stucki G. How to apply the International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health (ICF) for rehabilitation management in clinical practice. European journal of physical and rehabilitation medicine. 2008 Sep 1;44(3):329-42.

- ↑ Ustun, B., Chatterji, S. and Kostanjsek, N. (2004). Comments from WHO for the Journal of Rehabilitation Medicine Special Supplement on ICF core sets. Journal of Rehabilitation Medicine, 44(Supplement), 7–8.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 Taylor, WJ. and Geyh, S. Chapter 2 A Rehabilitation Framework: The International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health. In: Dean, SG., Siegert, RJ and Taylor, WJ. Interprofessional Rehabilitation: A Person-Centred Approach, First Edition. John Wiley & Sons, Ltd. pp 9 - 44

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 Rehabilitation in health systems: guide for action. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2019. Licence: CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO.

- ↑ Bossers, A. Miller L.T. Polatajko H.J. Hartley, M, (2002). Competency Based Fieldwork Evaluation for Occupational Therapists (CBFE) Delmar, Thompson Learning. USA.

- ↑ Alsop, A. & Ryan, S. (1996). Making the Most of Fieldwork Education: A Practical Approach, Chapman & Hall, London.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 Mills JA, Middleton JW, Schafer A, Fitzpatrick S, Short S, Cieza A. Proposing a re-conceptualization of competency framework terminology for health: a scoping review. Human Resources for Health. 2020;18(1):1-6.

- ↑ European Commission. The European Qualifications Framework for Lifelong Learning (EFQ) Luxembourg; 2008. Available from:http://www.ecompetences.eu/site/objects/download/4550_EQFbroch2008en.pdf.

- ↑ Physiotherapy Board of Australia & Physiotherapy Board of New Zealand. Physiotherapy practice thresholds in Australia and Aotearoa New Zealand; 2015.

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 Adapting the WHO Rehabilitation Competency Framework to a specific context: a stepwise guide for competency framework developers. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2020. Licence: CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO.

- ↑ World Health Organization. Rehabilitation. [Internet]. Geneva, Switzerland; 2020. [Cited 2021 July 1].

- ↑ Vos T, Lim SS, Abbafati C, Abbas KM, Abbasi M, Abbasifard M, Abbasi-Kangevari M, Abbastabar H, Abd-Allah F, Abdelalim A, Abdollahi M. Global burden of 369 diseases and injuries in 204 countries and territories, 1990–2019: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. The Lancet. 2020 Oct 17;396(10258):1204-22.

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 Mills JA, Cieza A, Short SD, Middleton JW. Development and Validation of the WHO Rehabilitation Competency Framework: A Mixed Methods Study. Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation. 2021 Jun 1;102(6):1113-23.

- ↑ World Health Organization and The World Bank. World report on disability. Geneva, Switzerland: WHO Press. 2011.

- ↑ Rehabilitation Competency Framework, Geneva, 12 September 2019. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2020. Licence: CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO.

- ↑ World Health Organization. Adapting the WHO rehabilitation competency framework to a specific context: a stepwise guide for competency framework developers.

- ↑ Rehabilitation Competency Framework, Geneva, 12 September 2019. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2020. Licence: CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO.

- ↑ Lester S. Professional standards, competence and capability. Higher Education, Skills and Work-based Learning. 2014 Feb 11.

- ↑ Government of Western Australia, Department of Health (2012)

- ↑ Integrated care pathway. IAHPC Pallipedia. Accessed August 15, 2021.

- ↑ Campbell H, Hotchkiss R, Bradshaw N, Porteous M.Integrated Care Pathways. Bmj. 1998 Jan 10;316(7125):133-7.

- ↑ Le Deist FD, Winterton J. What is Competence? Human Resource Development International. 2005 Mar 1;8(1):27-46.

- ↑ Bruno A, Bates I, Brock T, Anders on C. Towards a Global Competency Framework. American Journal of Pharmaceutical Education. 2010 Apr 12;74(3).