Osgood-Schlatter Disease

Original Editor - Casey Kirkes, Geoffrey De Vos as part of the Vrije Universiteit Brussel Evidence-based Practice Project

Top Contributors - Geoffrey De Vos, Admin, Keta Parikh, Sam Verhelpen, Nicolas D'Hondt, Kim Jackson, Michelle Lee, Scott Buxton, Laurens Dereymaeker, Jetse De Proft, Rachael Lowe, Wanda van Niekerk, Nicolas Everaerts, Casey Kirkes, Nikhil Benhur Abburi, Andeela Hafeez, Rucha Gadgil, Lucinda hampton, Jess Bell, Hanne Velghe, Uchechukwu Chukwuemeka, Vidya Acharya, Adam Vallely Farrell, 127.0.0.1, Tony Lowe, Claire Knott, Naomi O'Reilly and Rishika Babburu

Introduction[edit | edit source]

Osgood-Schlatter Disease (OSD), or osteochondrosis, or tibial tubercle apophysitis, or traction apophysitis of the tibial tubercle, is a common cause of anterior knee pain in the skeletally immature athletic population. Clinically, it presents as atraumatic, insidious anterior knee pain, with tenderness at the patellar tendon insertion site at the tibial tuberosity.[1] The condition occurs secondary to repetitive extensor mechanism stress activities such as jumping and sprinting, as well as during sporting activities like Basketball, Volleyball, Sprinters, Gymnastic, Football.[1]

Overall treatment and management includes symptomatic treatment with ice and NSAIDs, activity modification and relative rest from aggravating activities, and lower extremities stretching regimen to alter underlying predisposing biomechanical factors.[1][2]

Image 1: Male with Osgood-Schlatter disease

Etiology[edit | edit source]

OSD usually develops during the stage of bone maturation (10-12 yrs in girls and 12-14 yrs in boys) . The underlying etiology can be attributed to the repeated traction over the tubercle leading to microvascular tears, fractures, and inflammation; which then presents as swelling, pain, and tenderness.

OSD is an overuse injury that mostly appears in active, adolescent patients. The repetitive strain and microtrauma results in irritation and in severe cases partial avulsion of the tibial tubercle apophysis. Rarely trauma may lead to a full avulsion fracture. Predisposing factors include poor flexibility of quadriceps and hamstrings or other evidence of extensor mechanism misalignment[3].

Risk factors for the disorder are[4]:

- Male gender

- Ages: male 12-15, girls 8-12

- Sudden skeletal growth

- Repetitive activities like jumping and sprinting

Epidemiology[edit | edit source]

OSD is one of the most common causes of knee pain adolescent athletes.[1]

- Usually occurs in adolescent growth spurts between ages 10 to 15 years for males and 8 to 13 years for females (11.4% in males, 8.3% in females)[5].

- Is more common in males and athletes that participate in sports that involve running and jumping.

- Symptoms present bilaterally in 20% to 30% of patients[6].

Relevant Anatomy[edit | edit source]

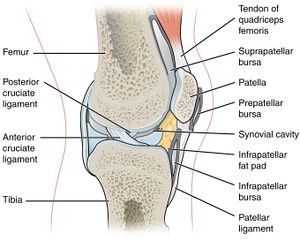

The tibial tubercle (the tuberosity of the tibia) is the protuberance along the anterior aspect of the tibia, just distal to the anterior surfaces of the medial and lateral tibial condyles. The tibial tubercle is entirely cartilaginous. It gives attachment to the patellar ligament or patellar tendon. The patellar tendon attaches to the tibial tuberosity inferior to the patella. Stress at this musculotendinous junction can cause pain and swelling.[7] The pain felt by the patient is mostly unilateral, but often it is bilateral.

Image 3: The insertion of patellar tendon at tibial tubercle

OSD is localized at the tibial tubercle, distal and anterior to the knee.

Clinical Presentation and Examination[edit | edit source]

Anterior knee pain associated with or without swelling, is the leading symptom in this disease and it aggravates during physical activities such as running, jumping, cycling, kneeling, walking up and down the stairs and kicking a ball(knee extension) . The clinical picture consists of pain localized to the area of the tibial tubercle.

- Painful palpation of the tibial tuberosity.

- Pain at the tibial tuberosity that worsens with physical activity or sport.

- Increased pain at the tibial tuberosity with sports activity.

- In some cases increased bony protuberance at the tibial tuberosity.

- Secondary to pain,Ely's test- there is tightness of Quadriceps.

- Resisted isometrics of the Quadricep muscle is painful.[8]

Differential Diagnosis[edit | edit source]

Conditions that show similar presentation:

- Jumper’s knee (patellar tendinitis) or Sinding- Larsen-Johanssen syndrome[8]

- Synovial plica injury[8]

- Tibial tubercle fracture[8]

- Osteochondroma of the proximal tibia.[8]

- Fat Pad Syndrome

These diseases are also localized at the patellar tendon and can cause similar knee problems.

Diagnostic Procedures[edit | edit source]

Radiological imagining is usually not required, and is done in severe cases or if an avulsion is suspected.

Image 4: Lateral view X-ray of the knee demonstrating fragmentation of the tibial tubercle with overlying soft tissue swelling.

- The diagnosis is based on typical clinical findings (see clinical presentation). [10]

- Radiographic examinations of both knees should always be performed, in both the anterior-posterior and lateral projections, to rule out the possibility of tumors, fractures, ruptures or infections. A picture of prominent tibial tubercle with soft tissue swelling, calcification of the patellar tendon, or free bony fragment proximal to the tubercle can be seen.

- An utmost care must be taken, for accurate diagnosis, as sometimes the tibial protuberance may not be pathological. Therefore, clinical correlation must be done.

Prognosis[edit | edit source]

- Excellent prognosis.[8]

- The condition is self-limiting and hence recovers within a month

- Sometimes the pain may persist up to 2 years, if unnoticed or left untreated.

Medical Management[edit | edit source]

- Conservative treatment: Treatment should begin with rest, icing (RICE), activity modification and sometimes non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs.[8]

- Surgical treatment: Surgical procedures should be avoided until the child has grown up and the bone growth has been completed to avoid growth-plate arrest and the development of recurvatum and or valgus of the knee. Surgical treatment, we identified different surgical procedures such as drilling of the tibial tubercle, excision of the tibial tubercle (decreasing the size), longitudinal incision in the patellar tendon, excision of the ununited ossicle and free cartilaginous pieces (tibial sequestrectomy), insertion of bone pegs and/or a combination of any of these procedures. [11]

Physical Therapy Management[edit | edit source]

Pain Relief[edit | edit source]

- The pain usually subsides with the cessation of growth at the tibial tubercle.

- Ice application after activity reduces the anterior knee pain.[8]

- Limiting the sports activity, for 6-8 weeks is advisable.[8]

- Gentle stretch to Quadricep and Hamstring muscle ,along with strengthening of Vastus Medialis Oblique muscle decreases pain.[8][11]

- Patellar loading is decreased by patellar tapping/ McConnel tapping, and by the use of brace.[8]

Exercise Therapy[edit | edit source]

Low-intensity Quadriceps-strengthening exercises, such as isometric multiple- angle quadriceps exercises, are therefore instituted earlier in the conditioning program. High-intensity Quadriceps exercises and Hamstring stretching are introduced gradually and have been proven effective with high evidence rating. [11] Incorporation of high-intensity Quadricep exercise can intensify pain.

Shockwave[edit | edit source]

Extracorporeal Shockwave therapy is a treatment which has been discussed in the use of OSD but due to the low value evidence recommendations cannot be made for this treatment. [14]

Activity Limitation[edit | edit source]

Non-operative treatment of this disease is based on the same principles that apply all overuse injuries.

- Today, there is no need for total immobilization, or for totally refraining from athletic activities.

- Of vital importance is that the physician inform the parents, the coach, and the child athlete of the natural course of this disease.

The child should continue his normal physical activities, to the limit that the pain allows it, so lower intensity of frequency of exercising (activity modification). Also swimming, as a secondary athletic activity, is very good during this disease (no discomfort). Also knee-braces, tapes, slip-on knee support with an infrapatellar strap or pad are recommended and may help during physical activities and can reduce pain. [15]

Research by Gerulis et al [16]has shown that limitation of physical activity, physical load restriction, and conservative treatment are more effective than physical load restriction and activity limitation alone.

References[edit | edit source]

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 Smith JM, Varacallo M. Osgood Schlatter’s disease (tibial tubercle apophysitis).2019 Available: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK441995/ (accessed13.10.2021)

- ↑ Rathleff MS, Straszek CL, Blønd L, Thomsen JL. [Knee pain in children and adolescents]. Ugeskr Laeger. 2019 Mar 25;181(13)

- ↑ Midtiby SL, Wedderkopp N, Larsen RT, Carlsen AF, Mavridis D, Shrier I. Effectiveness of interventions for treating apophysitis in children and adolescents: protocol for a systematic review and network meta-analysis. Chiropr Man Therap. 2018;26:41.

- ↑ Watanabe H, Fujii M, Yoshimoto M, Abe H, Toda N, Higashiyama R, Takahira N. Pathogenic Factors Associated With Osgood-Schlatter Disease in Adolescent Male Soccer Players: A Prospective Cohort Study. Orthop J Sports Med. 2018 Aug;6(8):2325967118792192.

- ↑ Indiran V, Jagannathan D. Osgood-Schlatter Disease. N Engl J Med. 2018 Mar 15;378(11):e15.

- ↑ Nkaoui M, El Alouani EM. Osgood-schlatter disease: risk of a disease deemed banal. Pan Afr Med J. 2017;28:56.

- ↑ Baltaci G, Özer H, Tunay VB. Rehabilitation of avulsion fracture of the tibial tuberosity following Osgood-Schlatter disease. Knee Surgery, Sports Traumatology, Arthroscopy. 2004 Mar 1;12(2):115-8.

- ↑ 8.00 8.01 8.02 8.03 8.04 8.05 8.06 8.07 8.08 8.09 8.10 Vaishya R, Azizi AT, Agarwal AK, Vijay V. Apophysitis of the tibial tuberosity (Osgood-Schlatter Disease): a review. Cureus. 2016 Sep;8(9).

- ↑ Osmosis. Osgood-Schlatter disease - causes, symptoms, diagnosis, treatment, pathology. Available from: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=QHMrYB-Ghlo [last accessed 31/10/2021]

- ↑ Çakmak S, Tekin L, Akarsu S. Long-term outcome of Osgood-Schlatter disease: not always favorable. Rheumatology international. 2014;34(1):135.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 11.2 Gholve PA, Scher DM, Khakharia S, Widmann RF, Green DW. Osgood schlatter syndrome. Current opinion in pediatrics. 2007 Feb 1;19(1):44-50.

- ↑ McConnell Physiotherapy Group. MCCONNELL KNEE TAPING (OFFICIAL). Available from: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=WbHXYnwUwws [last accessed 31/10/2021]

- ↑ BraceAbility. Osgood-Schlatter Disease: Stretches & Exercises for Knee Pain. Available from: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=AEBanZBgFjo [last accessed 31/10/2021]

- ↑ Lohrer H, Nauck T, Schöll J, Zwerver J, Malliaropoulos N. Extracorporeal shock wave therapy for patients suffering from recalcitrant Osgood-Schlatter disease. Sportverletzung Sportschaden: Organ der Gesellschaft fur Orthopadisch-Traumatologische Sportmedizin. 2012 Dec;26(4):218.

- ↑ Reid C, Lim K, Henderson C. The use of dermoscopy amongst dermatology trainees in the United Kingdom. Br J Med Practr. 2018 Dec 1;11(2):16-9.

- ↑ Gerulis V, Kalesinskas R, Pranckevicius S, Birgeris P. Importance of conservative treatment and physical load restriction to the course of Osgood-Schlatter's disease. Medicina (Kaunas, Lithuania). 2004 Jan 1;40(4):363-9.