Strength Training

Welcome to Arkansas Colleges of Health Education School of Physical Therapy Musculoskeletal 1 Project. This space was created by and for the students at Arkansas Colleges of Health Education School in the United States. Please do not edit unless you are involved in this project, but please come back in the near future to check out new information!!

Original Editor - Manisha Shrestha

Top Contributors - Lucinda hampton, Manisha Shrestha, Cameron Wells, Kim Jackson, Tony Varela, Damon Harrell, Dante Gracia, Rucha Gadgil, Candace Goh and Wanda van Niekerk Welcome to Arkansas Colleges of Health Education School of Physical Therapy Musculoskeletal 1 Project. This space was created by and for the students at Arkansas Colleges of Health Education School in the United States. Please do not edit unless you are involved in this project, but please come back in the near future to check out new information!!Introduction[edit | edit source]

Strength training (also known as resistance exercise) increases muscle strength by making muscles work against a weight or force. Resistance exercise is considered a form of anaerobic exercise.[1]

- Different forms of strength training include using your own body weight, free weights, weight machines, resistance bands and plyometrics.

- A beginner needs to train two or three times per week to gain the maximum benefit.

- Individuals should complete a pre-participation health screening and consult with professionals e.g. doctor, exercise physiologist, physiotherapist or registered exercise professional, before starting a new fitness program.

- Optimal programs with specific goals, starting points, and progressions will give maximal results.

Principles of Strength Training[edit | edit source]

The basic principles of a strength training programme are:[2]

- Overload Principle: It is important to overload the musculoskeletal system over time to create and sustain physiological adaptations from strength training and to overcome accommodation of muscles.

- Specificity Principle: Adaptations are specific to the muscles trained.

- Progression/Periodization: Overloading should occur at an optimal level and time frame to maximize performance.

- Individuality: Each individual will have a different response to the training stimulus and thus programs need to be individually tailored.

- Reversibility: The effects of training will be lost if training stimulus is removed for an extended period of time.

Equipment of Strength Training[edit | edit source]

Different types of strength training include:[3]

- Body weight – can be used for squats, push-ups and chin-ups (convenient, especially when travelling or at work).

- Resistance bands – these provide resistance when stretched. They are portable and can be adapted to most workouts. The bands provide continuous resistance throughout a movement.

- Free weights – classic strength training tools such as dumbbells, barbells and kettlebells.

- Medicine balls or sand bags – weighted balls or bags.

- Weight machines – devices that have adjustable seats with handles attached either to weights or hydraulics.

- Suspension equipment – a training tool that uses gravity and the user's body weight to complete various exercises.

Designing a Strength (Resistance)Program[edit | edit source]

It is important to pay attention to safety and form in order to reduce the risk of injury. When planning a protocol, the main things to consider are:[4]

- Choice, this principle gives individuals the autonomy and the ability to have a level of control over their training program that is tailored toward their personal goals, preferences, and potential. By giving individuals choice, you can elicit a response to promote adherence, engagement, and motivation to their program. Overall, this principle can provide a more efficient training regimen and create an opportunity for a successful strength program.

- Order-this principle refers to the strategic arrangement of exercises incorporated within a training program. The order in which exercise are performed can have a direct impact with the efficiency and overall progress towards strength and functional. The biggest takeaway from this principle is to allow maximum performance for each exercise.[5] Other principles to consider with order: Exercise selection, Priority of Exercise, Multi-joint before Single-joint, Fatigue Consideration.

- Frequency- this principle refers to how often an individual trains a certain muscle group within a designated time frame to improve strength or restoration of an impairment. This principle focuses the attention on finding a well-balanced relationship between training frequency and recovery to allow for quality strength gain and restoration of impairments.

- Intensity- When designing a strength exercise plan the intensity of the plan will vary based on the individual's fitness level. The rate of perceived exertion scale (RPE) can be used as an intensity measure to make the exercise plan specific to the individual. Individuals can use the modified RPE scale, which is a scale that goes from 1-10, one being very easy and ten being maximal effort.[6]

- Volume, Rest, And Type of Muscle Strengthening Volume can be attributed to how many repetitions, sets, or times an individual exercises weekly. Strength training should be performed more than two times a week for results.[7] Here are guidelines for multi-joint exercises like squats and bench.

- Strength

Weight greater than 85% of 1 rep max, 2-6 sets, and less than 6 reps each with a 2-5minute rest in between sets.[7]

Power

- 80-90% of 1 rep max weight, 3-5 sets, 1-2 reps, with a 2-5 minute rest break.[7]

Hypertrophy

-67-85% of 1 rep max weight, 3-6 sets, 6-12 reps, 30-90second rest period.[7]

Muscular Endurance

-Less than 67% of one rep max, 2-3 sets, greater than 12 reps, less than 30-second rest periods.[7]

6. Progression of strength training should be tailored to each individual's level of exertion, as indicated by the Rate of Perceived Exertion (RPE) scale and their one-rep max. As individuals become stronger, they should progressively increase the weight used for their exercises. Another aspect of progression involves adjusting the speed of the exercises. Slowing down the pace of an exercise can heighten its difficulty. Other factors such as range of motion, time under tension, and torque are considered when advancing exercises.18

Designing a strength (resistance) training program requires careful considerations and specific planning. The best strength training program is one tailored to personal goals. Below are the 4 types of resistance programs.

Strength

Objective: Achieve gains in muscular strength, focusing on both concentric and eccentric contractions. "Develop overall muscle strength and improve performance in activities requiring force production. Training should emphasize agendas that merge maximal strength and speed."[8]

Design Considerations: Incorporate compound exercises targeting major muscle groups, such as squats, deadlifts, bench presses, and rows. "Training heavy with a weight that can only be done for 6 or less reps (greater than or equal to 85% of 1 rep max) for 2-6 sets resting 2-5 minutes between each set."[8]

Benefits: "Staying consistent with a strength program leads to increased bone strength, endurance, strength, and muscle tone. Balance and coordination will improve, as will a decrease in the risk of injury. Thus, making activities of daily living easier." [9]

Power

Objective: To develop explosiveness and speed, enhance the ability to generate maximal force in minimal time, crucial for activities requiring quick movements, such as sprinting, jumping, and throwing.

Design Considerations: "Single effort lifts should be 80-90% of 1RM with 1-2 reps, while multiple effort lifts should be 75-85% of 1RM, with 3-5 reps. Both should be 3-5 sets with 2–5-minute rest period between sets."[8]"When training for power, it is important to perform exercises with a relatively high speed, a load, and explosive intent."[10]

Benefits: Enhances explosive power and speed. Improves neuromuscular coordination and motor unit recruitment. "Can complement other training programs to enhance overall athletic performance that can translate to functional activities in real life."[8]

Hypertrophy

Objective: Promote muscle growth and increase muscle size (hypertrophy) through resistance training in a specific way. Focusing on looking "aesthetic.

Design considerations: "Incorporate moderate to high volume training with moderate loads 67-85% of 1RM in sets of 3-6 and doing 6-12 reps while resting 30-90 seconds between sets."[8] Focus on compound exercises that engage the core. Isolation exercise should be included to target specific muscle groups such as biceps, triceps, and shoulder. In order to maximize hypertrophy gains, progressive overload is always encouraged, so increasing weight, reps, sets or even decreasing rest time.

Benefits: "Better mobility and functional capacity, increased strength, muscle, and bone mass, improved quality of life factors, reduced body fat, increased metabolic rate, lower blood pressure and cardiovascular strain during physical activity, improved blood lipid profile, and lower risk of type II diabetes."[11]

Muscular Endurance

Objective: Enhance muscular endurance and stamina through extended exercise duration and resistance to fatigue. Improve cardiovascular fitness and aerobic capacity, which are essential for activities that require prolonged efforts.

Design considerations: "To promote muscular endurance, incorporate resistance exercises with high repetition and low-to-moderate load. Training with weight that is less than or equal to 67% of 1RM, 2-3 sets, in a rep range of 12 or more, and resting 30 seconds or less between sets."[8]

Benefits: "Endurance training leads to adaptations in both the musculoskeletal system and cardiovascular systems, which contributes to an overall improvement in performance and exercise capacity."[12] Can also reduce the risk of overuse injuries caused by repetitive movements.

Effects of Strength Training[edit | edit source]

Strength training stimulates a variety of positive neuromuscular adaptations that enhance both physical and mental health. Physical and mental health benefits that can be achieved through resistance training include:

- Improved muscle strength and tone.

- Maintaining flexibility, mobility and balance, which can help maintain independence in ageing.

- Weight management and increased muscle-to-fat ratio – might be even more beneficial than aerobic exercise for fat loss.[1]

- May help reduce or prevent cognitive decline in older people.

- Greater stamina – as you grow stronger, you won’t get tired as easily.

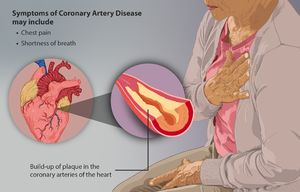

- Prevention or control of chronic diseases such as diabetes, coronary artery disease, arthritis, back pain, depression and obesity.

- Pain management

- Improved posture.

- Decreased risk of injury.

- Increased bone density and strength and reduced risk of osteoporosis.

- Improved sense of wellbeing – resistance training may boost self-confidence, improve body image and mood.

- Improved sleep and avoidance of insomnia.

- Increased blood glucose utilization.

- Reduced resting blood pressure.

- Improved blood lipid profiles.

- Increased gastrointestinal transit speed

Strength Exercises and Chronic Diseases[edit | edit source]

People with Chronic disease can all benefit from exercise eg diabetes, asthma, metabolic syndrome, cardiovascular disease, low back pain, arthritis , joint pain, depression, (COPD).

- Strength training can improve muscle strength and endurance, make it easier to do daily activities, slow disease-related declines in muscle strength, and provide stability to joints.

Obesity

- Sedentary living leads to muscle loss, metabolic slowdown, and fat gain.

- Presently, almost 70% of American adults are overfat and at increased risk for chronic diseases and other health problems. Regular endurance exercise is performed by less than 5% of the adult population (USA).

- Strength training provides a practical way for combating obesity and for eliciting physiological and psychological improvements that positively impact quality of life.

- Basic and brief strength training sessions have proved to be effective for rebuilding muscle, recharging metabolism, reducing fat, and enhancing a variety of health and fitness factors[14]

Cardiovascular Disease (CVD)

- The magnitude of resistance exercise-induced reductions in SBP (5–6 mmHg) and DBP (3–4 mmHg) are associated with an 18% reduction of major cardiovascular events (Blood Pressure Lowering Treatment Trialists Collaboration, 2014)

- Mcleod et al, 2019 recommended low-to moderate intensity resistance exercise training(RET) (30–69% of 1RM) is safe and effective even in individuals with CVD or at risk for developing CVD.[15]

- A comprehensive resistance-training program of 8 to 10 exercises for 20 to 30 minutes with an intensity of ≈50±10% of 1 RM with a minimum of 2 days per week and, if time permits, progress to 3 days per week is recommended. Exercise need to be done at a comfortably hard level (13 to 15 on the RPE [rating of perceived exertion]) and without Valsalva maneuver. Progression of exercise can be done by increasing 5 % of weight if the participant can comfortably lift the weight for up to 12 to 15 repetitions. If the participant cannot complete the minimum number of repetitions (8 or 10) using good technique, the weight should be reduced.[16]

Type 2 Diabetes

- American Diabetes Association, 2014 has reported lifestyle modifications (i.e. diet and exercise) were associated with a greater reduction on glycemic control than medication with more emphasis on aerobic exercise training. However, there are other studies showing benefits of resistance exercise on glycemic control.

- There is a contradictory result showing the level of intensity of resistance exercises in glycemic control. But the study done by Mcleod et al. 2019, recommends the inclusion of general whole-body resistance exercises twice in week in routine without worrying about exercise intensity.[15]

- There is a role for resistance exercise in reducing cancer risk, cancer recurrence, cancer mortality, and improving prognosis during adjuvant therapies. In breast[17] and prostate cancer, resistance exercise has been apparent. Further work needs to be done to address the optimal dose, intensity, and mechanisms specific to resistance exercise-induced benefits to cancer.[15]

Strength and the Older Population[edit | edit source]

With an increase in age, there comes various co-morbidities and frailty.

- Frailty, sarcopenia and osteoporosis are most common conditions which cause a decline in physical mobility and increased risk of falls.[1]

- Resistance exercises can play a vital role in the improvement of functional mobility. Resistance exercise is a potent stimulus for muscle hypertrophy and increasing bone density which is affected by sarcopenia and osteoporosis.

- Resistance exercise incorporated with combined exercise training ( balance exercise, aerobic exercises) has shown to be the best strategy for improvement in functional mobility in older adults. [18]

- Recent evidence shows that the recommended amounts of protein may be too low for elderly people and improved protein intake combined with strength exercises are hugely beneficial.[19]. See Muscle Function and Protein

- See: Age and Exercise; Physical Activity in Ageing and Falls; Muscle Function: Effects of Aging

Repetition Maximum for Weight Training[edit | edit source]

A repetition maximum (RM) is the most weight a person can lift for a defined number of exercise movements.

- E.g. a 10RM would be the heaviest weight a person could lift for 10 consecutive exercise repetitions. RM is a good measure of a persons current strength level.

One Repetition Maximum (1RM) is defined as the maximal weight an individual can lift for only one repetition with correct technique.

- The 1RM test is most commonly used by strength and conditioning coaches to assess strength capacities, strength imbalances, and to evaluate the effectiveness of training programmes.[1]

- By establishing 1RM and tracking it, you are able to observe a persons progress. It is a precise measure, so it can help judge how effective the program is.

It can be either calculated directly using maximal testing or indirectly using submaximal estimation methods.

- There are many different formulas to estimate your 1RM, all with slightly different calculations. The most popular (and proven accurate1) one is the Brzycki formula from Matt Brzycki[20]:

weight / ( 1.0278 – 0.0278 × reps )

If you just managed to lift 100 kg for five reps, you’d calculate your 1RM like this:

100 / ( 1.0278 - 0.0278 × 5 ) = 112.5 kg

How to Safely Test 1RM

While 1RM is a very useful tool, it does have limitations. Measuring your 1RM is not simply a matter of grabbing the biggest weight and getting a person to perform a rep. By definition, you will be stressing this muscle to its maximum and placing person at risk of an injury if you don't do it correctly. You need to prepare to do it properly. For e.g.

- Choose which move you are going to test (squat, bench press, etc.).

- Person warms up with light cardio activity and dynamic stretching for at least 15 to 30 minutes.

- Person performs 6 to 10 reps of chosen move using a weight that's about half of what you think their max will be. Then allow a rest for at least one to two minutes.

- Increase the weight up to 80% of what you think max might be. person performs three reps, then rests for at least one minute.

- Add weight in approximately 10% increments and person attempts a single rep each time, resting for at least one to two minutes in between each attempt.

- The maximum weight successfully lifted, with good form and technique, is 1RM.

Resources[edit | edit source]

- Resistance Exercise in Individuals With and Without Cardiovascular Disease-American Heart Association

- Effects of weight-lifting or resistance exercise on breast cancer-related lymphedema: A systematic review

- How lifting weights could improve your body and your mind

Related Pages[edit | edit source]

- Comparison between the DeLorme and Oxford Principles of Strength Training

- Strength Training versus Power Training

- Strength and Conditioning

- Strength training in prepubescents

References[edit | edit source]

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 Sundell J. Resistance training is an effective tool against metabolic and frailty syndromes. Advances in preventive medicine. 2011;2011.

- ↑ Cissik JM. Basic principles of strength training and conditioning. NSCA’s Performance Training Journal.2002:1(4), 7-11.

- ↑ Schoenfeld, B, Snarr, R.L. NSCA's Essentials of Personal Training. 3rd Edition. Human Kinetics. 2021.

- ↑ Brown L. Strength Training (2nd Edition). NSCA, Human Kinetics, 2007.

- ↑ Spreuwenberg, L.P.B., Kraemer, W.J., Spiering, B.A., Volek, J.S., Hatfield, D.L., Silvestre, R. (2006). Influence of exercise order in a resistance-training exercise session. Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research, 20(01), 141-144.

- ↑ Haddad M, Stylianides G, Djaoui L, Dellal A, Chamari K. Session-RPE method for training load monitoring: validity, ecological usefulness, and influencing factors. Front Neurosci. 2017;11:612.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 7.3 7.4 Liguori G, American College of Sports Medicine. ACSM's Guidelines for Exercise Testing and Prescription. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2020.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 8.2 8.3 8.4 8.5 Haff G, Triplett NT. Essentials of Strength Training and Conditioning. 4th ed. Champaign, IL: Human Kinetics; 2016.

- ↑ Witstein J. Starting a strength training program - OrthoInfo - AAOS. Orthoinfo. August 2023. https://orthoinfo.aaos.org/en/staying-healthy/starting-a-strength-training-program/

- ↑ Rogers P. How to improve strength and speed through weight training. Verywell Fit. December 7, 2019. https://www.verywellfit.com/weight-training-for-power-3498521

- ↑ Wolfe RR. The underappreciated role of muscle in health and disease. Am J Clin Nutr. 2006;84(3):475–482. https://doi.org/10.1093/ajcn/84.3.475

- ↑ Brooks GA. Bioenergetics of exercising humans. Comprehensive Physiology. 2012;537–562.

- ↑ John Spencer Ellis. Physiological Adaptation to Resistance Training - FITNESS EDUCATION REVIEW.Available from: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=fKzfse5hdyI [last accessed 26/5/2020]

- ↑ Westcott W. ACSM strength training guidelines: Role in body composition and health enhancement. ACSM's Health & Fitness Journal. 2009 Jul 1;13(4):14-22.

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 15.2 Mcleod JC, Stokes T, Phillips SM. Resistance exercise training as a primary countermeasure to age-related chronic disease. Frontiers in physiology. 2019 Jun 6;10:645.

- ↑ American Heart Association Journal. Resistance Exercise in Individuals With and Without Cardiovascular Disease. Available from: https://www.ahajournals.org/doi/full/10.1161/01.cir.101.7.828. [Last accessed: 26-05-2020]

- ↑ Wanchai A, Armer JM. Effects of weight-lifting or resistance exercise on breast cancer-related lymphedema: a systematic review. International journal of nursing sciences. 2019 Jan 10;6(1):92-8.

- ↑ Mcleod JC, Stokes T, Phillips SM. Resistance exercise training as a primary countermeasure to age-related chronic disease. Frontiers in physiology. 2019 Jun 6;10:645.

- ↑ Morton RW, Traylor DA, Weijs PJ, Phillips SM. Defining anabolic resistance: implications for delivery of clinical care nutrition. Current opinion in critical care. 2018 Apr 1;24(2):124-30.Available

- ↑ M. Brzycki. Strength Testing-Predicting One-Repetition Max from Reps-to-Fatigue. Journal of Physical Education, Recreation & Dance, 1993, Vol. 64, No. 1, pp. 8890.