Colorectal Cancer

Original Editors - Jacqueline Lopez Abby Schnur from Bellarmine University's Pathophysiology of Complex Patient Problems project.

Top Contributors - Jacqueline Lopez, Abigail Schnur, Lucinda hampton, Elaine Lonnemann, Kirenga Bamurange Liliane, Admin, Kim Jackson, Vidya Acharya, Aminat Abolade, Michelle Laine, Evan Thomas and George Prudden

Introduction[edit | edit source]

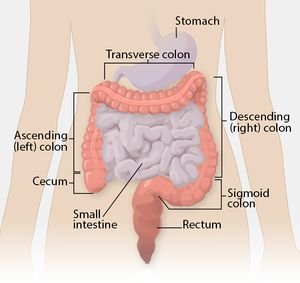

Colorectal cancer (CRC) is a rapid abnormal cell growth that affects the large intestines and/or rectum.

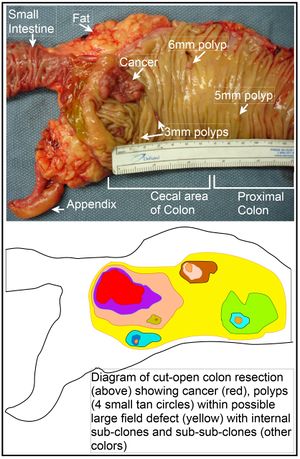

- These clusters of cells are called adenomatous polyps and develop from the tissue membrane of glandular tissue.

- Polyps can start as benign and non-cancerous but with time can develop and become cancerous.[1]

Colorectal cancer

- Third most common cancer diagnosed in both men and women in the U.S.

- Death rate from colorectal cancer has been dropping for the past 30 years but still the second leading cause of cancer death in the U.S.

- Overall lifetime risk of developing colorectal cancer is: 1 in 21 for men and 1 in 23 for women.

- There are currently more than one million colorectal cancer survivors in the U.S[2].

Epidemiology[edit | edit source]

Colorectal cancer (CRC) is one of the most common cancers

- CRC is one of the leading causes of cancer death worldwide - it is the second most common cause of cancer death in Europe and the United States

- Worldwide in 2008, 1.23 million cases of CRC were reported to be responsible for 9.7% of the total cancer burden, after lung (1.61 million cases) and breast cancer (1.38 million cases)

- It is the first frequently diagnosed cancer in Europe

- It is the 4th most frequently diagnosed cancer in the USA[3]

Approximately 20-25% of patients with CRC present with metastatic disease at the time of diagnosis and 20-25% of patients will develop metastases after treatment, resulting in a relatively high overall mortality rate of 40-45%[3]

- The lifetime risk of developing CRC is 1/20 or 4.96%.[4]

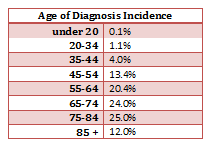

- The mean age of CRC diagnosis is 69 years of age. [5]

- The mean mortality age of CRC is 74 years of age. [5]

- Studies between 1991 and 2005 show that survival rates from CRC have increased by 30%. [6]

- The risk of getting CRC increases with age and is greater in men than women. [7]

- The most common area of diagnosis is the rectum and the rectosigmoid junction, with the sigmoid resulting the most favorable outcome. [8]

Etiology[edit | edit source]

Multifactorial etiology including: genetic factors; lifestyle; environmental risk factors (all have substantial effects on CRC development).

- Several risk factors have been identified for CRC (low-fibre and high-fat diet, physical inactivity, unhealthy diet, diabetes, obesity, smoking, high alcohol consumption, advanced age and inflammatory bowel disease). [9]

- However, more than one-half of all cases and deaths are attributable to modifiable risk factors, such as smoking, an unhealthy diet, high alcohol consumption, physical inactivity, and excess body weight, and thus potentially preventable

- In recent years, the increase in CRC incidence is attributed to the increase in the elderly population, changes in dietary habits and increased risk factors such as smoking, low physical activity and obesity[10].

- Lifestyle factors and obesity affect the development of various types of cancer, particularly CRC.

- Colon cancer originates from rapid cell proliferation of the epithelial cells called colonocytes that line the bowel, and somatic mutations in the p53 tumor-suppressor gene. The majority of CRCs are believed to occur sporadically leaving only about 10% to 20% of CRCs to have a known hereditary component

- A synergistic association is observed between physical inactivity and obesity. The International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC) has reported that 25% of all the cancer cases worldwide are caused by obesity and sedentary lifestyle[10]

Pathology[edit | edit source]

Colorectal cancers:

- 98% are adenocarcinomas, arising in the vast majority of cases from pre-existing colonic adenomas (neoplastic polyps), which progressively undergo a malignant transformation as they accumulate additional mutations ie the multihit hypothesis

- Metastases may be widespread in advanced disease, although the liver is by far the most common site involved.[11].

Clinical Presentation[edit | edit source]

Clinical presentation is typically insidious:

- Altered bowel habit (constipation and/or diarrhoea)

- Iron deficiency anaemia (chronic occult blood loss)

However initial manifestation may be acute:

- Bowel obstruction

- Intussusception (a painful form of bowel blockage in which one part of the intestine slides inside another part. It can cause swelling that can lead to intestinal damage).

- Heavy rectal bleeding

Occasionally metastatic disease may be the first sign.

Positive blood cultures or bacterial endocarditis with Streptococcus bovis is strongly suggestive of underlying colorectal cancer.

In general:

- Right sided tumours are larger and present with a mass, distant disease or iron deficiency anaemia

- Left sided tumours present earlier with altered bowel habit [11]

Common systemic symptoms of CRC include:

- Unexplained weight loss

- Unexplained loss of appetite

- Nausea or vomiting

- Diarrhea

- Anemia

- Jaundice

- Weakness or fatigue[12]

In many cases colorectal cancer is not discovered until it has become metastatic to other locations in the body. CRC most commonly metastasizes to the liver. It will also commonly metastasize to the lung, brain and bone, but it is uncommon to find one of these metastasis without the presence of a metastatic spread to the liver as well. [8]

Associated Co-morbidities[edit | edit source]

Approximately 51-59% of individuals with a diagnosis of CRC who are under the age of 70 do not also suffer from co-morbidities; however, in the individuals who are greater than 70 years of age, only 26-24% of them do not suffer from co-morbidities. Of this group greater than 70 years of age, the men have the highest prevalence of complicating co-morbid conditions. These conditions can have a marked impact on the treatment of the individual’s CRC diagnosis. The short-term survival is also worsened in the presence of co-morbid conditions, especially cardiovascular co-morbidities.

- Cardiovascular Disease

- Previously diagnosed CA

- Male – Large Bowel, Urinary Tract, Lung, and Prostate

- Female – Large Bowel, Breast, and Female Genital System

- Hypertension (F>M)

- Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease

- Diabetes[13]

Diagnostic Tests[edit | edit source]

In addition to a physical examination, the following tests may be used to diagnose colorectal cancer.

- Colonoscopy

- Allows the doctor to look inside the entire rectum and colon while a patient is sedated. If colorectal cancer is found, a complete diagnosis that accurately describes the location and spread of the cancer may not be possible until the tumor is surgically removed.

- Biopsy removal of a small amount of tissue for examination under a microscope).

- Molecular testing of the tumor. Results of these tests can help determine your treatment options.

- All colorectal cancers should be tested for problems in mismatch repair proteins, called a mismatch repair defect (dMMR).

- For metastatic or recurrent colorectal cancer, a sample of tissue from the area where it spread or recurred is preferred for testing, if available.

- Blood Tests

- CRC often bleeds into the large intestine or rectum, people with the disease may become anemic. A test of the number of red cells in the blood, which is part of a complete blood count (CBC), can indicate that bleeding may be occurring.

- Another blood test detects the levels of a protein called carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA). High levels of CEA may indicate that a cancer has spread to other parts of the body.

- Computed tomography (CT or CAT) scan.

- Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI). MRI is the best imaging test to find where the colorectal cancer has grown.

- Ultrasound

- Endorectal ultrasound is commonly used to find out how deeply rectal cancer has grown and can be used to help plan treatment. However, this test cannot accurately detect cancer that has spread to nearby lymph nodes or beyond the pelvis. Ultrasound can also be used to view the liver, although CT scans or MRIs (see above) are better for finding tumors in the liver.

- Chest X-Ray - An x-ray of the chest can help doctors find out if the cancer has spread to the lungs.

- Positron Emission Tomography (PET) or PET-CT scan.

- A PET scan is usually combined with a CT scan (see above), called a PET-CT scan. A PET scan is a way to create pictures of organs and tissues inside the body.[14]

Therapeutic Management[edit | edit source]

The therapeutic management of CRC should involve a multi-modal approach, including high-quality surgery and an optimal choice of chemotherapy and radiotherapy regimens according to disease characteristics and patient preferences. Even in the case of metastatic disease, the optimal multi-modal treatments could achieve potential cure or long-term survival benefit in some patients.

- The management of colorectal cancer (CRC) should be undertaken using a multi-modal approach, taking into account the extent, localization and biology of the tumor, as well as individual patient factors.

- The application of targeted agents has shown much promise in the treatment of metastatic CRC. Predictive markers are important in the individualization of the optimal treatment. The future offers hope that patients will have individualized therapies based on their tumor genetics.[15]

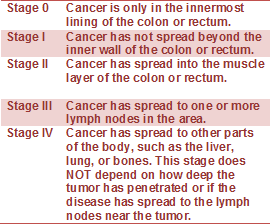

- Treatment involves local control with resection in almost all cases. Adjuvant chemotherapy is reserved for stage III disease.

- Overall 5-year survival rate is 40-50%, with the stage at operation the single most important factor affecting prognosis.

Surgical Options

- Polypectomy is a procedure in which polyps (small growths on the inner lining of the colon) are removed during a colonoscopy.

- Local excision can be used to treat cancers in the rectum. The procedure involves removing the cancer and some tissue of the wall of the rectum. It may be done through the anus or through a small cut in the rectum. The procedure does not require major abdominal surgery.

- Resection involves the removal of part, or all, of the colon along with the cancer and its attaching tissues.

- Laparoscopic surgery. To perform laparoscopy, between 3 and 6 small (5-10 mm) incisions are made in the abdomen. The laparoscope and special laparoscopic instruments are inserted through these small incisions. The surgeon is then guided by the laparoscope, which transmits a picture of the intestinal organs on a video monitor.

Physical Therapy Management[edit | edit source]

Physical therapy is used after a diagnosis of CRC to help build strength and endurance to continue to perform daily activities (ADLs). Exercise or physical activity has positive effects on the functional capacity of patients in preoperative prehabilitation, in the early postoperative period and for the duration of their survival[16].The goal is that basic ADLs will not exhaust the clients and have energy for additional activities.

- A cross-sectional study in patients recently diagnosed with colorectal cancer comparing their muscle mass, core strength, and physical fragility with those of healthy subjects showed reduced muscle mass and power in the abdominal and lumbar muscles suggesting better outcomes in these patients with an early introduction of strength-enhancing programs[17].

- Exercise or physical activity appears to reduce the risk of cancer recurrence and mortality, and is capable of improving patient mobility, fatigue and sleep quality, thereby enriching the overall quality of life of advanced or stage IV CRC patients. It may also potentially have an effect on the level of predictive biomarkers for the outcome of CRC survivors.

- Physical activity of at least 18 MET-hours per week is considered to be a rational intensity of physical activity for CRC survivors to achieve a better outcome[16].

An oncology rehabilitation therapist is usually either an occupational or physical therapist; they have an expertise when treating people with cancer. These therapists create patient-specific exercise programs. The goals of these treatment programs include:

- Minimizing fatigue

- Optimizing physical function

- Boost their immune system

- Improve bowel habits

- Improve flexibility

- Reduce stress and anxiety

- Minimize depression

- Enhance self-image [18]

Physiotherapy helps through all stages of treatment Research shows better outcomes with

- Preoperative supervised home-based physiotherapy intervention (respiratory, strength, and aerobic)[19].

- After a CRC surgery - through the recovery process by regaining strength, mobility, and independence.eg helps maintain hip and spine ROM and strength (areas of negative impact from treatments).

- In the prevention of recurrence of colon cancer through physical activity presecription eg Physical Therapists are able to provide an individualized exercise program based on this evidence with an understanding of the current treatments for cancer and how they affect a person's ability to stay active and exercise.

Physical therapists can also help offset side effects of the CRC medical treatment.

- Lymphedema Management

- Some lymph nodes may be removed during surgery and that can interrupt the flow of lymph back to the center of the body. This treatment is used to decrease the swelling caused by this and also the pain and discomfort associated with this problem. See Manual Lymphatic Drainage (art gallery display of compression garments R)

2. Nutrition Therapy

Basic education can be provided or refer to a dietician if beyond therapists scope.

- Researchers estimate that eating a nutritious diet, getting enough exercise, and controlling body fat could prevent 45% of colorectal cancers.

- The National Cancer Institute recommends a low-fat diet that includes plenty of fiber and at least five servings of fruits and vegetables per day.

- Solid food may not be an option, depending on the stage and treatment.

3. Pain management

4. Acupuncture

Differential Diagnosis[edit | edit source]

Colorectal cancer may present and be mistaken as other medical conditions.

- Diverticulitis

- Inflammatory Bowel Disease

- Large Bowel Lymphoma[11]

References[edit | edit source]

- ↑ Colorectal cancer Available from:https://www.nfcr.org/blog/blog9-must-know-facts-colorectal-cancer/ (30.8.2020)

- ↑ National foundation for cancer research Colorectal cancer Available from:https://www.nfcr.org/blog/blog9-must-know-facts-colorectal-cancer/ (last accessed 29.8.2020)

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 Nakayama G, Tanaka C, Kodera Y. Current options for the diagnosis, staging and therapeutic management of colorectal cancer. Gastrointestinal tumors. 2014;1(1):25-32.Available from:https://www.karger.com/Article/Fulltext/354995 (last accessed 30.8.2020)

- ↑ Colorectal Cancer Overview [Internet]. American Cancer Society. 2013 [updated 2013 Jan 17]. Available from: http://www.cancer.org/cancer/colonandrectumcancer/overviewguide/colorectal-cancer-overview-key-statistics.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 Seer Stat Facts Sheets: Colon and Rectum [Internet]. National Cancer Institute. 2012 [updated 2011 Nov]. Available from: http://seer.cancer.gov/statfacts/html/colorect.html.

- ↑ Enzinger PC, Benson AB, Mitchell EP, et al. Medical Update on Colorectal Cancer Understanding KRAS [pamphlet]. New York: Elsevier Oncology; 2010.

- ↑ Colorectal (Colon) Cancer [Internet]. Center for Disease Control. 2012 [updated 2012 Oct 22]. Available from: http://www.cdc.gov/cancer/colorectal/index.htm.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 Tidy, Colin MD. Colorectal Cancer [Internet]. Patient.co.uk; 2012 [updated 2012 July 19]. Available from: http://www.patient.co.uk/doctor/colorectal-adenocarcinoma.htm.

- ↑ Siegel RL, Miller KD, Goding Sauer A, Fedewa SA, Butterly LF, Anderson JC, Cercek A, Smith RA, Jemal A. Colorectal cancer statistics, 2020. CA: a cancer journal for clinicians. 2020 May;70(3):145-64.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 Oruç Z, Kaplan MA. Effect of exercise on colorectal cancer prevention and treatment. World journal of gastrointestinal oncology. 2019 May 15;11(5):348.Available from:https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6522766/ (last accessed 30.8.2020)

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 11.2 Radiopedia CRC Available from:https://radiopaedia.org/articles/colorectal-carcinoma ( last accessed 30.8.2020)

- ↑ Colorectal Cancer: Integrative Treatment Program [Internet]. Cancer Treatment Centers of America. 2012. Available from: http://www.cancercenter.com/colorectal-cancer.cfm.

- ↑ De Marco MF, Janssen-Heijnen ML, Van Der Heijden LH, et al. Comorbidity and colorectal cancer according to subsite and stage: a population-based study. Eur J Cancer. 2000 Jan; 36(1): 95-9

- ↑ Cancernet CRC Available from:https://www.cancer.net/cancer-types/colorectal-cancer/diagnosis (last accessed 30.8.2020)

- ↑ Nakayama G, Tanaka C, Kodera Y. Current options for the diagnosis, staging and therapeutic management of colorectal cancer. Gastrointestinal tumors. 2014;1(1):25-32. Available from:https://www.karger.com/Article/Fulltext/354995 (last accessed 30.8.2020)

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 Wong CL, Lee HH, Chang SC. Colorectal cancer rehabilitation review. Journal of Cancer Research and Practice. 2016 Jun 1;3(2):31-3.Available from:https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S2311300616300088 (last accessed 30.8.2020)

- ↑ Cruz-Fernández M, Achalandabaso-Ochoa A, Gallart-Aragón T, Artacho-Cordón F, Cabrerizo-Fernández MJ, Pacce-Bedetti N, Cantarero-Villanueva I. Quantity and quality of muscle in patients recently diagnosed with colorectal cancer: a comparison with cancer-free controls. Supportive Care in Cancer. 2020 Jan 22:1-8.

- ↑ http://cedarhillpt.com/2010/01/stretch-yourself-a-2010-challenge-from-cedar-hill/clipart-illustration-of-an-orange-man-sitting-on-a-gym-floor-and/

- ↑ Karlsson E, Farahnak P, Franzen E, Nygren-Bonnier M, Dronkers J, van Meeteren N, Rydwik E. Feasibility of preoperative supervised home-based exercise in older adults undergoing colorectal cancer surgery–A randomized controlled design. PloS one. 2019;14(7).