Lymphoma

Original Editor - Lucinda hampton

Top Contributors - Lucinda hampton, Kim Jackson, Vidya Acharya and Areeba Raja

Introduction[edit | edit source]

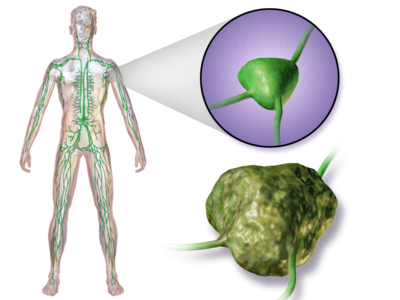

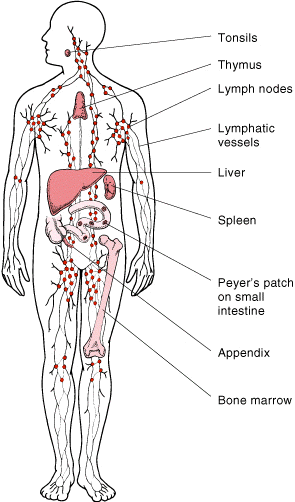

Lymphoma is a cancer of the lymphatic system, arising from lymphocytes or lymphoblasts [a large, immature lymphocyte that has been activated by an antigen and divides to give rise to mature lymphocytes (B cells and T cells)].

The lymphatic system includes the lymph nodes (lymph glands), spleen, thymus gland and bone marrow.

Lymphoma can be restricted to the lymphatic system or can arise as extranodal disease. This, along with variable aggressiveness results in a diverse imaging appearance[1].

Many types of lymphoma exist. The main subtypes are:

- Hodgkin's lymphoma (formerly called Hodgkin's disease)

- Non-Hodgkin's lymphoma[2]

Lymphoma cure rates are comparatively high (up to 90%) compared to many other malignancies.

Prognosis depends not only on histological subtype and grade but also on stage, hence why imaging plays a pivotal role in treatment. Aggressive lymphomas (e.g. Burkitt lymphoma) typically have a prognosis of weeks without treatment[1].

Lymphoma treatment may involve chemotherapy, immunotherapy medications, radiation therapy, a bone marrow transplant or some combination of these.

Epidemiology[edit | edit source]

- Lymphoma accounts for ~4% of all cancers . They are more common in developed countries.

- In children, lymphoma accounts for 10-15% of all cancers, being the third most common form of malignancy.[1]

Etiology[edit | edit source]

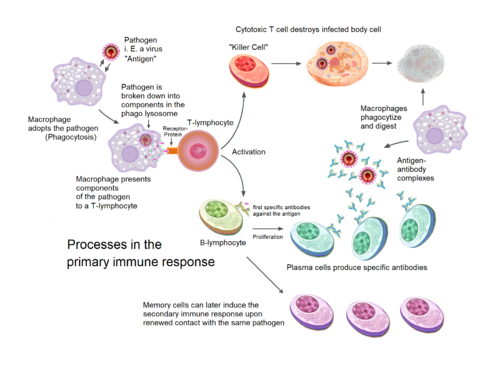

Lymphomas are a malignancy that arise from mature lymphocytes. The aetiology is unknown but potential lymphomatogenic risk factors include:

- Viral infection, e.g. EBV, HTLV-1, HIV, HCV, HSV

- Bacterial infection, e.g. Helicobacter pylori

- Chronic immunosuppression, e.g. post-transplantation

- Prior chemotherapy (especially alkalising agents) and drug therapy, e.g. digoxin[1]

The aetiology is unknown however it begins

- When a disease-fighting white blood cell (lymphocyte) develops a genetic mutation.

- The mutation tells the cell to multiply rapidly, causing many diseased lymphocytes that continue multiplying.

- The mutation also allows the cells to go on living when other normal cells would die.

- This causes too many diseased and ineffective lymphocytes in the lymph nodes and causes the lymph nodes, spleen and liver to swell[2].

Classification[edit | edit source]

Lymphomas are currently classified according to the 2008 WHO classification of tumours of haematopoietic and lymphoid tissues. The main division is into:

- Hodgkin lymphoma (Hodgkin disease) (40%)

- non-Hodgkin lymphoma (60%)

- mature B-cell lymphoma

- mature T-cell and NK-cell lymphoma

- post-transplant lymphoproliferative disorders

The majority (85%) of lymphomas are B-cell with the remainder (15%) being T-cell.

Clinical presentation[edit | edit source]

Lymphoma can present as nodal or extranodal disease.

- Hodgkin lymphoma and low-grade non-Hodgkin lymphoma (NHL) classically present as nodal disease, whereas

- High-grade NHL can present with complications from mass effect such as superior vena cava obstruction, cauda equina syndrome, etc.

- Extranodal disease can affect any organ[1].

Lymphoma can often present with B symptoms. The B symptoms (a.k.a. inflammatory symptoms) are a triad of systemic symptoms associated with more advanced disease and a poorer outcome in lymphoma.[3]B symptoms are a poor prognostic factor in lymphoma (both Hodgkin and non-Hodgkin lymphomas[3]. The triad shown below:

- weight loss: >10% unintentional decrease in body weight in the 6 months preceding the diagnosis

- fever: >38°C

- night sweats

Other Symptoms include

- Painless swelling of lymph nodes neck, armpits or groin

- Persistent fatigue

- Shortness of breath

- Itchy skin

Diagnosis[edit | edit source]

Tests and procedures used to diagnose lymphoma include

- A physical and subjective examination

- Lymph node biopsy to check for cancer cells.

Other tests to help diagnose, stage, or manage lymphoma:

- Bone marrow aspiration or biopsy.

- Chest X-ray.

- MRI.

- PET scan (uses a radioactive substance to look for cancer cells in the body).

- Molecular test (looks for changes to genes, proteins, and other substances in cancer cells to help diagnose the type of lymphoma)

- Blood tests (checks the number of certain cells, levels of other substances, or evidence of infection in the blood).[4]

Treatment[edit | edit source]

Blood cancers, including lymphoma, are extremely heterogeneous, and can involve a variety of treatment options, often in combination.

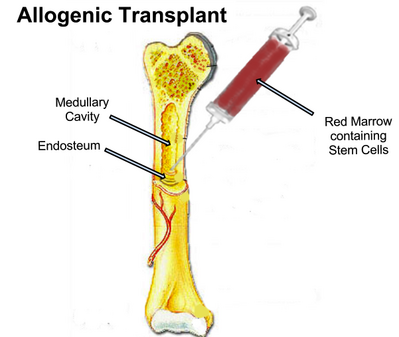

- Some form of chemotherapy, radiation therapy, immunotherapy, or a combination is typically used to treat Hodgkin lymphoma. Bone marrow or stem cell transplantation may also sometimes be done under special circumstances. Most patients with Hodgkin lymphoma live long and healthy lives following successful treatment.

- Many people treated for non-Hodgkin lymphoma will receive some form of chemotherapy, radiation therapy, biologic therapy, immunotherapy, or a combination of these. Bone marrow, stem cell transplantation, or CAR T-cell therapy may sometimes be used. Surgery may be used under special circumstances, but primarily to obtain a biopsy for diagnostic purposes.

- Although “indolent” or slow growing forms of non-Hodgkin lymphoma are not currently curable, the prognosis is still very good. Patients may live for 20 years or more following an initial diagnosis. In certain patients with an indolent form of the disease, treatment may not be necessary until there are signs of progression. Response to treatment can also change over time. Treatment that worked initially may be ineffective the next time, making it necessary to always keep abreast of the latest information on new or experimental treatment options.[5]

Which lymphoma treatments are used depends on the type and stage of the disease, clients overall health, and preferences.

The goal of treatment is to destroy as many cancer cells as possible and bring the disease into remission.

Lymphoma treatments include:

- Active surveillance. Some forms of lymphoma are very slow growing (Undergo periodic tests to monitor condition).

- Chemotherapy.

- Radiation therapy.

- Bone marrow transplant. A bone marrow transplant, also known as a stem cell transplant, involves using high doses of chemotherapy and radiation to suppress bone marrow. Then healthy bone marrow stem cells from clients body or from a donor are infused into your blood where they travel to bones and rebuild your bone marrow. See also Chronic Graft Versus Host Disease

- Other treatments. Other drugs used to treat lymphoma include targeted drugs that focus on specific abnormalities in your cancer cells. Immunotherapy drugs use your immune system to kill cancer cells. A specialized treatment called chimeric antigen receptor (CAR)-T cell therapy takes the body's germ-fighting T cells, engineers them to fight cancer and infuses them back into the body[2].

Outlook[edit | edit source]

Ordinarily, our immune system protects us from harm. In lymphoma, however, elements of it turn against us and become a malignant force.

- Therapy for one form of the disease, Hodgkin’s lymphoma, has been improving: advances in treatment mean that about 85% of people now survive for at least five years after diagnosis. For other forms of the disease eg.non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma, the outlook for patients is poorer. However research is deepening our understanding of all forms of this class of cancer, and brings hope for more effective therapies.

- A disease must first be diagnosed. The advent of liquid biopsies that detect small pieces of tumour DNA circulating in the blood is bringing greater precision to this task: circulating DNA can indicate both the tumour’s size and the mutations behind it.

- The standard, reasonably successful treatments for lymphoma are chemo- and radiotherapy. However these therapies will lead to heart problems and other forms of cancer later in life for some. An array of new treatments are being developed, guided in part by work with a strikingly good animal model of the human disease: dogs.

- Researchers are developing a gene-modifying treatment called chimeric (see below) antigen receptor T-cell therapy, in which a person’s immune system is altered to seek and destroy tumour cells. And drugs known as Bruton’s tyrosine kinase inhibitors are emerging: these block a molecule in the signalling pathway that turns some white blood cells cancerous. Work is also under way to make vaccines against lymphomas, and progress in treating graft-versus-host disease could open the door to more options for stem-cell therapy[6].

NB Chimeric: Relating to a monoclonal antibody produced from the cells of an organism, usually a mouse, in which the constant region has been replaced with a human sequence of amino acids. This is done in the laboratory by replacing part of the DNA sequence in the nonhuman cells of an organism with a sequence of human DNA.

Resources[edit | edit source]

References[edit | edit source]

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 Radiopedia Lymphoma Available from:https://radiopaedia.org/articles/lymphoma?lang=gb (last accessed 29.7.2020)

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 Mayo clinic Lymphoma Available from:https://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/lymphoma/symptoms-causes/syc-20352638 (last accessed 29.7.2020)

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 Radiopedia B symptoms Available from:https://radiopaedia.org/articles/b-symptoms?lang=gb (last accessed 29.7.2020)

- ↑ WebMD Lymphoma Available from:https://www.webmd.com/cancer/lymphoma/lymphoma-cancer#2 (last accessed 29.7.20200

- ↑ Lymphoma organisation Lymphoma Available from:https://lymphoma.org/aboutlymphoma/treatments/ (last accessed 29.7.2020)

- ↑ Nature Lymphoma Available from:https://www.nature.com/articles/d41586-018-07359-0 (last accessed 29.7.2020)