Specific Low Back Pain: Difference between revisions

(reference formatting and linking with other PP pages) |

m (Changed protection settings for "Specific Low Back Pain" ([Edit=⧼protect-level-volunteer⧽] (indefinite) [Move=⧼protect-level-volunteer⧽] (indefinite))) |

||

| (25 intermediate revisions by 5 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

<div class="editorbox"> '''Original Editor '''- [[User:Michelle Lee|Michelle Lee]] '''Top Contributors''' - {{Special:Contributors/{{FULLPAGENAME}}}}</div> | <div class="editorbox"> '''Original Editor '''- [[User:Michelle Lee|Michelle Lee]] '''Top Contributors''' - {{Special:Contributors/{{FULLPAGENAME}}}}</div> | ||

| Line 8: | Line 7: | ||

[[Low Back Pain|Low back pain]] is a considerable health problem in all developed countries and is most commonly treated in primary healthcare settings. It is usually defined as pain, muscle tension, or stiffness localised below the costal margin and above the inferior gluteal folds, with or without leg pain (sciatica). The most important symptoms of low back pain are pain and disability.. | [[Low Back Pain|Low back pain]] is a considerable health problem in all developed countries and is most commonly treated in primary healthcare settings. It is usually defined as pain, muscle tension, or stiffness localised below the costal margin and above the inferior gluteal folds, with or without leg pain (sciatica). The most important symptoms of low back pain are pain and disability.. | ||

About 90% of all patients with low back pain will have non-specific low back pain, which, in essence, is a diagnosis based on exclusion of specific pathology.<ref> | About 90% of all patients with low back pain will have non-specific low back pain, which, in essence, is a diagnosis based on exclusion of specific pathology.<ref>Koes BW, Van Tulder MW. Clinical Review, Diagnosis and treatment of low back pain. BMJ 2006;332:1430</ref> Those specific pathologies can be defined as: | ||

*[[Radiculopathy]] | *[[Radiculopathy]] | ||

*[[Disc Herniation]] | *[[Disc Herniation|Disc herniation]] | ||

*[[Lumbar | *[[Lumbar Spinal Stenosis]] | ||

*[https://www.physio-pedia.com/Spondylolisthesis Spondylolisthesis] | *[https://www.physio-pedia.com/Spondylolisthesis Spondylolisthesis] | ||

*[http://www.physio-pedia.com/Ankylosing_Spondylitis Ankylosing | *[http://www.physio-pedia.com/Ankylosing_Spondylitis Ankylosing spondylitis] | ||

*[http://www.physio-pedia.com/Osteoporosis Osteoporosis] | *[http://www.physio-pedia.com/Osteoporosis Osteoporosis] | ||

*[http://www.physio-pedia.com/Lumbar_Spine_Fracture Lumbar | *[http://www.physio-pedia.com/Lumbar_Spine_Fracture Lumbar spine fracture] | ||

*[http://www.physio-pedia.com/Skeletal_Metastases Skeletal | *[http://www.physio-pedia.com/Skeletal_Metastases Skeletal metastases] | ||

*[[Cauda_Equina_Syndrome]] | *[[Cauda_Equina_Syndrome|Cauda equina syndrome]] | ||

*[[Scheuermanns Disease|Scheuermans | *[[Scheuermanns Disease|Scheuermans disease]] | ||

*[[Scoliosis]] | *[[Scoliosis]] | ||

== Clinically | == Clinically relevant anatomy == | ||

The human spine is a self-supporting construction of skeleton, cartilage, ligaments and [[Muscle|muscles]]. The lower back (where most back pain occurs) includes the five vertebrae in the lumbar region and supports much of the weight of the upper body. The spaces between the vertebrae are maintained by intervertebral discs that act like shock absorbers throughout the spinal column to cushion the bones as the body moves. Ligaments hold the vertebrae in place, and tendons attach the muscles to the spinal column. Thirty-one pairs of nerves are rooted to the spinal cord and they control body movements and transmit signals from the body to the brain. | The human spine is a self-supporting construction of skeleton, cartilage, ligaments and [[Muscle|muscles]]. The [[Lumbar Anatomy|lower back]] (where most back pain occurs) includes the five vertebrae in the lumbar region and supports much of the weight of the upper body. The spaces between the vertebrae are maintained by intervertebral discs that act like shock absorbers throughout the spinal column to cushion the bones as the body moves. Ligaments hold the vertebrae in place, and tendons attach the muscles to the spinal column. Thirty-one pairs of nerves are rooted to the spinal cord and they control body movements and transmit signals from the body to the brain. | ||

See [[Lumbar Anatomy]] for more information. | See [[Lumbar Anatomy|lumbar anatomy]] for more information. | ||

=== Epidemiology/Etiology<nowiki/>'''<nowiki/>'''''<nowiki/>'' === | === Epidemiology/Etiology<nowiki/>'''<nowiki/>'''''<nowiki/>'' === | ||

Low back pain is a symptom, not a disease, and has many causes. It is generally described as pain between the costal margin and the gluteal folds. It is extremely common. About 40% of people | Low back pain is a symptom, not a disease, and has many causes. It is generally described as pain between the costal margin and the gluteal folds. It is extremely common. About 40% of people report having had low back pain within the past 6 months. Onset usually begins in the teens to early 40s. A small percentage of low back pain becomes chronic.<ref>Randall L. [https://books.google.co.za/books?hl=en&lr=&id=dxd4Kcy1StYC&oi=fnd&pg=PP1&dq=physical+Medicine+and+Rehabilitation.&ots=UHRNd8rGsa&sig=tBqIvU39A-2MuCIwFufxd-Qit-c#v=onepage&q=physical%20Medicine%20and%20Rehabilitation.&f=false Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation.] 4th edition. Elseiver 2002. p871</ref><ref>Hoy D, Brooks P, Blyth F, Buchbinder R. [https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S1521694210000884 The epidemiology of low back pain.] Best practice & research Clinical rheumatology 2010;24(6):769-81.</ref> Low back pain is considered acute if its onset occurred less than 1 month ago. The symptoms of chronic low back pain have lasted 2 months or longer. Both acute and chronic low back pain may be further classified as non-specific or specific/radicular.<ref>Majid K, Truumees E. [https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1040738308000178 Epidemiology and natural history of low back pain.] Seminars in Spine Surgery 2008;20(2):87-92.</ref> | ||

== Characteristics/ Clinical Presentation == | == Characteristics/ Clinical Presentation == | ||

=== [[Scoliosis]]<ref>Johari J, Sharifudin MA, Ab Rahman A, Omar AS, Abdullah AT, Nor S, Lam WC, Yusof MI. [https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4728701/ Relationship between pulmonary function and degree of spinal deformity, location of apical vertebrae and age among adolescent idiopathic scoliosis patients.] Singapore medical journal 2016;57(1):33. </ref> === | |||

*Not much pain | *Not much pain | ||

| Line 48: | Line 47: | ||

*Local ligament pain | *Local ligament pain | ||

< | === [[Scheuermanns Disease|Scheuermann's disease]]<ref name=":3" /><ref>Ristolainen L, Kettunen JA, Heliövaara M, Kujala UM, Heinonen A, Schlenzka D. [https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s00586-011-2075-0 Untreated Scheuermann’s disease: a 37-year follow-up study.] European Spine Journal 2012;21(5):819-24. </ref><ref name=":7" /> === | ||

*History of deformity because of structural [[kyphosis]] in adolescence | |||

*In the lumbar spine, hyper-lordosis can occur | |||

* | *Strong correlation between Scheuermann’s disease and [[scoliosis]] | ||

* | *[[Hamstrings|Hamstring]] tightness | ||

*Back pain, located distal to the apex of the deformity | *Back pain, located distal to the apex of the deformity | ||

| Line 70: | Line 66: | ||

*Neurological symptoms | *Neurological symptoms | ||

*In severe cases: | *In severe cases: Heart and lung function can be impaired. Other secondary changes are Schmorl nodes, irregular vertebral endplates and dics space narrowing | ||

*Muscle spasms or muscle cramps | *Muscle spasms or muscle cramps | ||

| Line 78: | Line 74: | ||

*Limited flexibility | *Limited flexibility | ||

=== [[Ankylosing Spondylitis (Axial Spondyloarthritis)|Ankylosing spondylitis]]<ref>Andersson BJG, Thomas W. McNeill. Lumbar Spine Syndromes: Evaluation and Treatment. Springer-Verlag, 1989.</ref><ref>Baaj AA, Mummaneni PV, Uribe JS, Vaccaro AR, Greenberg MS. [https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3280004/ Handbook of Spine Surgery.] 1st Edition. New York: Thieme, 2012.</ref><sup> </sup> === | |||

'''5 phases''' | |||

*Acute inflammation | *Acute inflammation | ||

| Line 96: | Line 87: | ||

*Components of the joint grow towards each other and form 1 piece | *Components of the joint grow towards each other and form 1 piece | ||

'''Important symptoms''' | |||

*Iridocyclitis or uveïtis (inflammation of the iris) | *Iridocyclitis or uveïtis (inflammation of the iris) | ||

| Line 108: | Line 99: | ||

*Respiratory complaints | *Respiratory complaints | ||

*Inflammation of achilles tendons | *Inflammation of [[Achilles Tendon|achilles tendons]] | ||

*Psoriasis ( | *[[Psoriatic Arthritis|Psoriasis]] (skin condition) | ||

*Intestinal problems ([[Crohn's Disease]]) | *Intestinal problems ([[Crohn's Disease]]) | ||

| Line 116: | Line 107: | ||

*Peripheral joints, eyes, skin and the cardiac and intestinal systems problems | *Peripheral joints, eyes, skin and the cardiac and intestinal systems problems | ||

*The hips, shoulder and knees are the most commonly and most severely affected of the extremity joints | *The [[Hip Anatomy|hips]], [[shoulder]] and [[Knee|knees]] are the most commonly and most severely affected of the extremity joints | ||

*Complaints of intermittent breathing difficulties because of a decrease in chest expansion | *Complaints of intermittent breathing difficulties because of a decrease in chest expansion | ||

*Also fatigue, weight loss and fever are indirect effects of inflammation processes. This can lead to severe psychological issues such as | *Also fatigue, weight loss and fever are indirect effects of inflammation processes. This can lead to severe psychological issues such as [[depression]]. | ||

< | === [[Disc Herniation|Disc herniation]]<ref>American Association of Neurological Surgeons. Herniated disc. Available from: https://www.aans.org/Patients/Neurosurgical-Conditions-and-Treatments/Herniated-Disc (accessed 01/02/2020).</ref><sup> </sup> === | ||

'''Herniated disc not pressing on the nerve:''' | |||

*<u></u>No pain | *<u></u>No pain | ||

'''Herniated disc pressing on the nerve(s):''' | |||

*<u></u>Stiffness | *<u></u>Stiffness | ||

| Line 144: | Line 132: | ||

The severity of the complaints depends on the strength of compressive from the hernia on surrounding components. | The severity of the complaints depends on the strength of compressive from the hernia on surrounding components. | ||

=== Radicular syndrome<ref>Konstantinou K, Dunn KM, Ogollah R, Vogel S, Hay EM. [https://link.springer.com/article/10.1186/s12891-015-0787-8 Characteristics of patients with low back and leg pain seeking treatment in primary care: baseline results from the ATLAS cohort study.] BMC musculoskeletal disorders 2015;16(1):332. </ref><ref>Van Boxem K, Cheng J, Patijn J, Van Kleef M, Lataster A, Mekhail N, Van Zundert J. [https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1111/j.1533-2500.2010.00370.x Lumbosacral radicular pain.] Pain Practice 2010;10(4):339-58. </ref> === | |||

*Sharp, dull, piercing, throbbing, stabbing, shooting or burning pain | *Sharp, dull, piercing, throbbing, stabbing, shooting or burning pain | ||

*Numbness, tingling and weakness in the arms or legs | *Numbness, tingling and weakness in the arms or legs | ||

*Radicular pain in one leg | *[[Radiculopathy|Radicular pain]] in one leg | ||

*Neurological loss of function | *Neurological loss of function | ||

| Line 162: | Line 147: | ||

*Paravertebral pressure above the nerve root causes pain in the periphery | *Paravertebral pressure above the nerve root causes pain in the periphery | ||

*Failure of the sensible dermatome | *Failure of the sensible [[Dermatomes|dermatome]] | ||

*Nerve root entrapment such as sensory deficits, [[Reflexes|reflex]] changes or muscle weakness | |||

=== [[Lumbar Spinal Stenosis|Spinal canal stenosis]]<ref>Siebert E, Prüss H, Klingebiel R, Failli V, Einhäupl KM, Schwab JM. [https://www.nature.com/articles/nrneurol.2009.90 Lumbar spinal stenosis: syndrome, diagnostics and treatment.] Neurology 2009;5(7):392-403.</ref><ref>Spine-health. What is Spinal Stenosis? Available from: http://www.spine-health.com/conditions/spinal-stenosis/what-spinal-stenosis (accessed 01/02/2020). </ref><ref>Kraus Back and Neck Institute. Stenosis – Pain and other symptoms. Available from: http://www.spinesurgery.com/conditions/stenosis (accessed 01/02/2020). </ref> === | |||

*Persisting and heavy pain in the low back | *Persisting and heavy pain in the low back | ||

*Referred pain in legs | *[[Radiculopathy|Referred]] pain in legs | ||

*Symptoms increase when standing straight | *Symptoms increase when standing straight | ||

*Laying down/ sitting down/ bending forward decreases the pain | *Laying down/sitting down/bending forward decreases the pain | ||

*Areas off the body who are not in pain, can feel itchy and inflamed | *Areas off the body who are not in pain, can feel itchy and inflamed | ||

| Line 196: | Line 178: | ||

*Neurogenic intermittent claudication | *Neurogenic intermittent claudication | ||

=== [[Spondylolisthesis|Spondylolisthesis]]<ref>Wicker A. [https://journals.co.za/content/ismj/9/2/EJC48630 Spondylolysis and spondylolisthesis in sports: FIMS Position Statement.] International Sport Med Journal 2008;9(2):74-8. </ref> === | |||

*Instability | *Instability | ||

*Low back pain | *[[Low Back Pain|Low back pain]] | ||

*Stiffness in | *Stiffness in lower back | ||

*Pain | *Pain with extension | ||

*Referred pain in upper leg | *Referred pain in upper leg | ||

| Line 222: | Line 201: | ||

*Disturbance in patterns | *Disturbance in patterns | ||

*Diminished | *Diminished spinal range of motion | ||

*Disturbances in coordination and balance | *Disturbances in coordination and [[balance]] | ||

*Neurological symptoms (possible evolution towards cauda equina syndrome) | *Neurological symptoms (possible evolution towards [[Cauda Equina Syndrome|cauda equina syndrome]])<br> | ||

<br | |||

=== Metastases<ref name=":9">Linton SJ, Halldén K. [https://journals.lww.com/clinicalpain/Abstract/1998/09000/Can_We_Screen_for_Problematic_Back_Pain__A.7.aspx Can we screen for problematic back pain? A screening questionnaire for predicting outcome in acute and subacute back pain.] The Clinical journal of pain 1998;14(3):209-15.</ref> === | |||

*Pain increases at night and in rest | *Pain increases at night and in rest | ||

*Paralysis | *Paralysis | ||

*Compression on the spinal cord resulting in numbness or tingling in the abdomen and legs, bowel and bladder problems, difficulty walking | *Compression on the spinal cord resulting in numbness or tingling in the abdomen and legs, bowel and bladder problems, difficulty walking | ||

=== [[Cauda Equina Syndrome|Cauda equina syndrome]] (CES)<ref name=":10">Van Tulder MW, Assendelft WJ, Koes BW, Bouter LM. [https://journals.lww.com/spinejournal/Abstract/1997/02150/Spinal_Radiographic_Findings_and_Nonspecific_Low.15.aspx Spinal radiographic findings and nonspecific low back pain.] A systematic review of observational studies. Spine 1997;22:427-34.</ref> === | |||

*Difficulties to urinate | *Difficulties to urinate | ||

| Line 260: | Line 235: | ||

*Lumbar muscular strain/sprain | *Lumbar muscular strain/sprain | ||

*[[Lumbar Compression Fracture]] | *[[Lumbar Compression Fracture|Lumbar compression fracture]] | ||

'''Systemic''' | '''Systemic''' | ||

| Line 269: | Line 244: | ||

'''Referred''' | '''Referred''' | ||

*[[Abdominal Aortic Aneurysm]] | *[[Abdominal Aortic Aneurysm|Abdominal aortic aneurysm]] | ||

*[[Pancreatitis]] | *[[Pancreatitis]] | ||

*[[Nephrolithiasis (Kidney Stones)|Nephrolithiasis]] | *[[Nephrolithiasis (Kidney Stones)|Nephrolithiasis]] | ||

== Diagnostic | == Diagnostic procedures == | ||

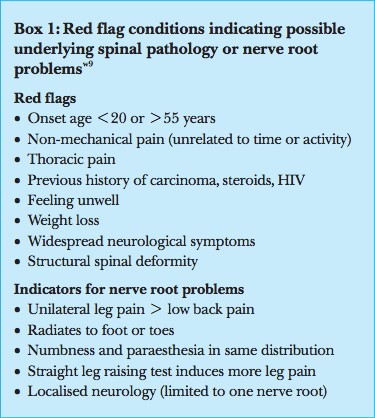

In clinical practice, the triage is focused on identification of | In clinical practice, the triage is focused on identification of “[[Red Flags in Spinal Conditions|red flags]]” (see box 1/2) as indicators of possible underlying pathology, including nerve root problems. When [[Red Flags in Spinal Conditions|red flags]] are not present, the patient is considered as having non-specific low back pain. Besides those [[Red Flags in Spinal Conditions|red flags]] there are [[Yellow Flags|yellow flags]]. “[[Yellow Flags|Yellow flags]]” have been developed for the identification of patients at risk of chronic pain and disability. A screening instrument based on these yellow flags has been validated for use in clinical practice.<ref name=":9" /> The predictive value of the [[Yellow Flags|yellow flags]] and the screening instrument need to be further evaluated in clinical practice and research. | ||

[[Image:GBox 1.jpg|frame|left]] | [[Image:GBox 1.jpg|frame|left]] | ||

| Line 291: | Line 266: | ||

<br> | <br> | ||

<br> | <br> | ||

< | Abnormalities in [[X-Rays|x-ray]] and [[MRI Scans|magnetic resonance imaging]] and the occurrence of non-specific low back pain seem not to be strongly associated.<ref name=":10" /> Abnormalities found when imaging people without back pain are just as prevalent as those found in patients with back pain. Van Tulder and Roland reported radiological abnormalities varying from 40% to 50% for degeneration and spondylosis in people without low back pain. They reported that radiologists should include this epidemiological data when reporting the findings of a radiological investigation.<ref>Roland M, Van Tulder M. Should radiologists change the way they report plain radiography of the spine? Lancet 1998;352:348-9.</ref> Many people with low back pain show no abnormalities. In clinical guidelines these findings have led to the recommendation to be restrictive in referral for imaging in patients with non-specific low back pain. Only in cases with [[Red Flags in Spinal Conditions|red flag]] conditions might imaging be indicated. Jarvik et al reported that [[CT Scans|computed tomography]] and [[MRI Scans|magnetic resonance imaging]] are equally accurate for diagnosing lumbar [[Disc Herniation|disc herniation]] and [[Lumbar Spinal Stenosis|stenosis]] — both conditions that can easily be separated from non-specific low back pain by the appearance of [[Red Flags in Spinal Conditions|red flags]]. [[MRI Scans|Magnetic resonance imaging]] is probably more accurate than other types of imaging for diagnosing infections and malignancies,<ref>Jarvik JG, Deyo RA. [https://annals.org/aim/article-abstract/715687/diagnostic-evaluation-low-back-pain-emphasis-imaging Diagnostic evaluation of low back pain with emphasis on imaging.] Ann Int Med 2002;137:586-97.</ref> but the prevalence of these specific pathologies is low. | ||

== Outcome measures == | |||

The following list contains commonly used low back pain outcome measures. These questionnaires are complete and not patient specific. Often medical imaging has to be done to include specific low back pain disorders,but your own clinical judgement will be necessary to determine the most useful measure in your clinical setting. | |||

* [[Quebec Back Pain Disability Scale]] | |||

** A condition–specific questionnaire developed to measure the level of functional disability for patients with low back pain. Intended for those who suffer diseases such as acute [[Low Back Pain|low back pain]], [[Chronic Low Back Pain|chronic pain]], [[Lumbar Spinal Stenosis]], posterior surgical decompression. | |||

[[Oswestry Disability Index]]<sup></sup> | * [[Oswestry Disability Index]] | ||

** <sup></sup>Patient-completed questionnaire which gives a subjective percentage of level of function (disability) in activities of daily living in those during rehabilitation from low back pain in acute or [[Chronic Low Back Pain|chronic low back pain]]. | |||

* [https://www.physio-pedia.com/Roland_Morris_Disability_Questionnaire Roland-Morris Disability Questionnaire] | |||

** The patient is asked to tick off different statements when it is applied to him, that specific time. It is most sensitive for patients with mild to moderate disability. | |||

* [[Back Pain Functional Scale]] | |||

** A 12-item self-report measure that evaluates functional ability that is intended for people who are suffering from back pain. | |||

[[ | * [[Visual Analogue Scale]] | ||

== Examination == | |||

= Examination = | |||

The first aim of the physiotherapy examination for a patient presenting with back pain is to classify the patient according to the diagnostic triage recommended in international back pain guidelines. Serious and specific causes of back pain with neurological deficits are rare but it is important to screen for these conditions. Serious conditions account for 1-2% of people presenting with low back pain. When serious and specific causes of low back pain have been ruled out individuals are said to have non-specific (or simple or mechanical) back pain. | The first aim of the physiotherapy examination for a patient presenting with back pain is to classify the patient according to the diagnostic triage recommended in international back pain guidelines. Serious and specific causes of back pain with neurological deficits are rare but it is important to screen for these conditions. Serious conditions account for 1-2% of people presenting with low back pain. When serious and specific causes of low back pain have been ruled out individuals are said to have non-specific (or simple or mechanical) back pain. | ||

The examination consists of | The examination consists of: | ||

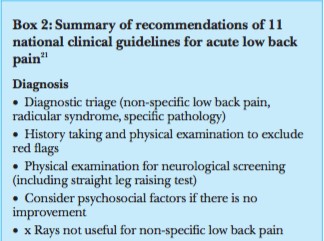

=== Observation === | |||

<u></u> | |||

*How does the patient enter the room? | *How does the patient enter the room? | ||

*A posture deformity in flexion or a deformity with a lateral pelvic tilt, possibly a slight limp, may be seen. | *A posture deformity in flexion or a deformity with a lateral pelvic tilt, possibly a slight limp, may be seen. | ||

*How does the patient sit down and how comfortably/ uncomfortably does he or she sit? | *How does the patient sit down and how comfortably/uncomfortably does he or she sit? | ||

*How does the patient get up from the chair? A patient with low back pain may splint the spine in order to avoid painful movements. | *How does the patient get up from the chair? A patient with [[Low Back Pain|low back pain]] may splint the spine in order to avoid painful movements. | ||

*Posture: look out for scoliosis ([[Adam's forward bend test]]), excessive lordosis or kyphosis. | *Posture: look out for scoliosis ([[Adam's forward bend test]]), excessive lordosis or [[kyphosis]]. | ||

[[Image:Gtan fot5.jpg|frame|center]] | [[Image:Gtan fot5.jpg|frame|center]] | ||

{{#ev:youtube|6QUufpstXwY|300}} | |||

=== Other observations === | |||

*Body type | *Body type | ||

*Attitude | *Attitude | ||

| Line 340: | Line 308: | ||

*Skin | *Skin | ||

*Hair | *Hair | ||

*[[Leg Length Discrepancy]] (functional | *[[Leg Length Discrepancy|Leg length discrepancy]] (functional vs structural) | ||

{{#ev:youtube|Lo87BX7QUhA|300}} | |||

Active range of motion of the lumbar spine is evaluated with the patient standing. Motion of the lumbar spine occurs in 3 planes and includes 4 directions, as follows: | === Range of motion === | ||

Active range of motion of the [[Lumbar Anatomy|lumbar spine]] is evaluated with the patient standing. Motion of the lumbar spine occurs in 3 planes and includes 4 directions, as follows: | |||

*Forward flexion: 40°-60° | *Forward flexion: 40°-60° | ||

*Extension: 20°-35° | *Extension: 20°-35° | ||

*Lateral flexion/ side bending (left and right): 15°-20° | *Lateral flexion/side bending (left and right): 15°-20° | ||

*Rotation (left and right): 3°-18°<br> | *Rotation (left and right): 3°-18°<br> | ||

Strength testing of the lumbar spine includes the muscles around the spine column and the large moving muscles that attach onto the axial skeleton. The goal of muscle testing is to evaluate for strength and reproduction of pain.<br> | === Isometric muscle testing === | ||

Strength testing of the lumbar spine includes the muscles around the spine column and the large moving muscles that attach onto the axial skeleton. The goal of muscle testing is to evaluate for strength and reproduction of pain.<br> | |||

=== Palpation === | |||

The physician can use palpation for two purposes during examination of the lumbar spine: | The physician can use palpation for two purposes during examination of the lumbar spine: | ||

| Line 361: | Line 328: | ||

*To confirm findings previously demonstrated in the examination | *To confirm findings previously demonstrated in the examination | ||

=== Test for neurological dysfunction === | |||

[[Straight Leg Raise Test]]: | [[Straight Leg Raise Test]]: | ||

| Line 369: | Line 335: | ||

*Sensitivity of 35%-97% | *Sensitivity of 35%-97% | ||

*Specificity of 10%-100% | *Specificity of 10%-100% | ||

{{#ev:youtube|LdAD9GNv8FI|300}} | |||

[[Slump Test]]: | [[Slump Test]]: | ||

| Line 376: | Line 343: | ||

*Sensitivity of 44%-84% | *Sensitivity of 44%-84% | ||

*Specificity of 58%-83% | *Specificity of 58%-83% | ||

<nowiki>{{#ev:youtube|8Qknf8yyMFQ|300}}</nowiki> | |||

[[Femoral Nerve Tension Test]]:<br>The femoral nerve traction test is used to evaluate for pathology of the femoral nerve or nerve routes coming out of the third and fourth lumbar segments. | [[Femoral Nerve Tension Test]]:<br>The femoral nerve traction test is used to evaluate for pathology of the femoral nerve or nerve routes coming out of the third and fourth lumbar segments. | ||

{{#ev:youtube|h5YjDsngTN8|600}} | |||

[[Sacroiliac Compression Test]]: | [[Sacroiliac Compression Test]]: | ||

{{#ev:youtube|https://youtu.be/pWjvrhWMR4w?t=74}} | |||

'''6. Tests for Joint Dysfunction''' | |||

[[One Leg Standing Test (Gillet Test, Kinetic Test)|One Leg Standing Test]]: | [[One Leg Standing Test (Gillet Test, Kinetic Test)|One Leg Standing Test]]: | ||

| Line 389: | Line 359: | ||

*Sensitivity of 50%-55% | *Sensitivity of 50%-55% | ||

*Specificity of 46%-68% | *Specificity of 46%-68% | ||

{{#ev:youtube|dvhvKXnXAac}} | |||

[[FABER Test]] (flexion abduction external rotation test): | [[FABER Test]] (flexion abduction external rotation test): | ||

The flexion abduction external rotation (FABER) test is used to evaluate for pathology of the | The flexion, abduction, external rotation (FABER) test is used to evaluate for pathology of the [[Sacroiliac Joint]]. | ||

*Sensitivity of 54%-66% | *Sensitivity of 54%-66% | ||

*Specificity of 51%-62% | *Specificity of 51%-62% | ||

{{#ev:youtube|89Qiht82zmg}} | |||

[[Lumbar Quadrant Test]]: | [[Kemp Test|Lumbar Quadrant Test]]: | ||

This test is used to determine if the hip is the source of the patient's symptoms. A positive test is a reproduction of the patient's worst pain that they came with into the clinic. | This test is used to determine if the [[hip]] is the source of the patient's symptoms. A positive test is a reproduction of the patient's worst pain that they came with into the clinic. | ||

*Sensitivity: 75% | *Sensitivity: 75% | ||

*Specificity: 43%- 58% | *Specificity: 43%- 58% | ||

{{#ev:youtube|tBVhHpxF3ZQ|300}} | |||

{{#ev:youtube|4wIFZmxiSTg|300}} | |||

== Medical | == Medical management == | ||

=== [[Spondylolisthesis]] === | |||

'''General'''<ref>Kalichman L, Hunter DJ. [https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s00586-007-0543-3 Diagnosis and conservative management of degenerative lumbar spondylolisthesis.] European Spine Journal 2008;17(3):327-35.</ref><ref>Weinstein JN, Tosteson TD, Lurie JD, Tosteson AN, Blood E, Hanscom B, Herkowitz H, Cammisa F, Albert T, Boden SD, Hilibrand A. [https://www.nejm.org/doi/pdf/10.1056/nejmoa0707136 Surgical versus nonsurgical therapy for lumbar spinal stenosis.] New England Journal of Medicine 2008;358(8):794-810. </ref> | |||

*Initially resting and avoiding movements like lifting, bending and sports. | *Initially resting and avoiding movements like lifting, bending and sports. | ||

*Analgesics and | *Analgesics and non-steroidal anti-inflammatories reduce musculoskeletal pain and have an anti-inflammatory effect on nerve root and joint irritation. | ||

*Epidural steroid injections can be used to relieve low back pain, lower extremity pain related to radiculopathy and neurogenic claudication. | *Epidural steroid injections can be used to relieve low back pain, lower extremity pain related to radiculopathy and neurogenic claudication. | ||

*A brace may be useful to decrease segmental spinal instability and pain. [ | *A brace may be useful to decrease segmental spinal instability and pain.<ref>Belfi LM, Ortiz AO, Katz DS. [https://journals.lww.com/spinejournal/Abstract/2006/11150/Computed_Tomography_Evaluation_of_Spondylolysis.25.aspx Computed tomography evaluation of spondylolysis and spondylolisthesis in asymptomatic patients.] Spine 2006;31(24):E907-10. </ref> | ||

'''Surgery''' | '''Surgery''' | ||

Patients with chronic and disabling symptoms, who fail to respond to conservative management may be referred for surgery. | Patients with chronic and disabling symptoms, who fail to respond to conservative management may be referred for surgery.<ref>Monticone M, Ferrante S, Teli M, Rocca B, Foti C, Lovi A, Bruno MB. [https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s00586-013-2889-z Management of catastrophising and kinesiophobia improves rehabilitation after fusion for lumbar spondylolisthesis and stenosis. A randomised controlled trial.] European spine journal 2014;23(1):87-95.</ref> | ||

=== [[Scoliosis]] === | |||

Patients with early-onset scoliosis, defined as a lateral curvature of the spine under the age of 10 years, are offered surgical treatment when the major curvature remains progressive despite conservative treatment ([[Cobb's angle]] 50° or more). Spinal fusion is not recommended in this age group, as it prevents spinal growth and pulmonary development.<ref name=":0">Kaspiris A, Grivas TB, Weiss HR, Turnbull D. [https://scoliosisjournal.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/1748-7161-6-12 Surgical and conservative treatment of patients with congenital scoliosis: α search for long-term results.] Scoliosis 2011;6(1):12.</ref> | |||

'''Conservative treatment:''' In conservative treatment, the use of braces mainly aims to prevent the progression of secondary curves that develop above and below the congenital curve, causing imbalance. In these cases, they may be applied until skeletal maturity.<ref name=":0" /> | |||

'''Surgical treatment:''' Spinal surgery in patients with congenital scoliosis is regarded as a safe procedure and many authors claim that surgery should be performed as early as possible to prevent the development of severe local deformities and secondary structural deformities that would require more extensive fusion later. Most of the time surgery is performed during adolescence, but newer techniques allow good correction to be accomplished into early adulthood. The goals for surgical treatment are to prevent progression and to improve spinal alignment and balance.<ref name=":0" /> | |||

<u> | === Radicular Syndrome === | ||

<u></u>Lumbar radicular syndrome can be treated in a conservative or a surgical way. The international consensus says that in the first 6-8 weeks, conservative treatment is indicated.<ref>Driscoll T, Sambrook PN. Best Practice and Research: Clinical Rheumatology. Best Practice and Research: Clinical Rheumatology 2011;25(1):1-2.</ref> Surgery should be offered only if complaints remain present for at least 6 weeks after a conservative treatment.<ref>Jacobs WC, van Tulder M, Arts M, Rubinstein SM, van Middelkoop M, Ostelo R, Verhagen A, Koes B, Peul WC. [https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s00586-010-1603-7 Surgery versus conservative management of sciatica due to a lumbar herniated disc: a systematic review.] European Spine Journal 2011;20(4):513-22.</ref> A surgical intervention for [[sciatica]] is called a discectomy and focuses on removal of [[Disc Herniation|disc herniation]] and eventually a part of the disc.<ref name=":1">Koes BW, Van Tulder MW, Peul WC. [https://www.bmj.com/content/334/7607/1313?flh= Diagnosis and treatment of sciatica.] Bmj 2007;334(7607):1313-7.</ref> See the page for [[Lumbar Radiculopathy|lumbar radiculopathy]] for further information | |||

=== [[Cauda Equina Syndrome]] === | |||

Once [[Cauda Equina Syndrome|cauda equina syndrome]] is diagnosed, emergent surgical decompression is recommended to avoid potential permanent neurological damage.<ref>Bin MA, Hong WU, Jia LS, Wen YU, Shi GD, Shi JG. [https://journals.lww.com/cmj/Fulltext/2009/05020/Cauda_equina_syndrome__a_review_of_clinical.19.aspx Cauda equina syndrome: a review of clinical progress.] Chinese medical journal 2009;122(10):1214-22.</ref> The role of surgery is to relieve pressure from the nerves in the cauda equina region and to remove the offending elements.<ref name=":2">Gardner A, Gardner E, Morley T. [https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s00586-010-1668-3 Cauda equina syndrome: a review of the current clinical and medico-legal position.] European Spine Journal 2011;20(5):690-7.</ref> | |||

=== [[Scheuermanns Disease|Scheuermann's disease]] === | |||

The treatment of Scheuermann’s disease depends on the patient’s age, degree of angulation, and estimated remaining growth. | |||

'''Non-operative treatment''' | |||

< | If the [[Thoracic Hyperkyphosis|thoracic kyphosis]] exceeds 40-45° during the growth period and if there are radiological signs of Scheuermann’s disease, non-operative treatment is indicated. This consists of bracing, casting and exercises.<ref name=":3">Wenger DR, Frick SL. [https://journals.lww.com/spinejournal/Citation/1999/12150/Scheuermann_Kyphosis.10.aspx Scheuermann kyphosis.] Spine 1999;24(24):2630.</ref><br> | ||

'''Operative treatment''' | |||

Patients with Scheuermann’s disease rarely undergo surgery because the natural history of the disease is in most cases benign. Conservative treatment is usually not effective for large curves (above 75°) or in the adult. Spinal pain and unacceptable cosmetic appearance are the most common indications for surgery. It’s important to be careful in counselling these patients because these criteria are subjective. As a result of this, there are also no evidence-based criteria for an indication of surgery.<ref name=":3" /><ref>Etemadifar M, Ebrahimzadeh A, Hadi A, Feizi M. [https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s00586-015-4234-1 Comparison of Scheuermann’s kyphosis correction by combined anterior–posterior fusion versus posterior-only procedure.] European Spine Journal 2016;25(8):2580-6.</ref><ref>Yanik HS, Ketenci IE, Coskun T, Ulusoy A, Erdem S. [https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s00586-015-4123-7 Selection of distal fusion level in posterior instrumentation and fusion of Scheuermann kyphosis: is fusion to sagittal stable vertebra necessary?.] European Spine Journal 2016;25(2):583-9.</ref> | |||

=== Lumbar Spinal Stenosis === | |||

If non-operative treatment has failed, surgical treatment may be considered. The key in deciding whether or not to have surgery is the degree of physical disability and disabling pain. In most cases of advanced claudication (spinal or vascular), a decompression surgery is required to alleviate the symptoms of [[Lumbar Spinal Stenosis|spinal stenosis]].<ref name=":4">Costa LO, Maher CG, Latimer J. [https://journals.lww.com/spinejournal/Abstract/2007/04200/Self_Report_Outcome_Measures_for_Low_Back_Pain_.16.aspx Self-report outcome measures for low back pain: searching for international cross-cultural adaptations.] Spine 2007;32(9):1028-37.</ref><br> | |||

Steroid injections and non-steroidal inflammatory medications can also be used to treat lumbar spinal stenosis.<ref name=":4" /><ref>Mazanec DJ, Podichetty VK, Hsia A. [https://mdedge-files-live.s3.us-east-2.amazonaws.com/files/s3fs-public/issues/articles/content_69_909.pdf Lumbar canal stenosis: start with nonsurgical therapy.] Cleveland Clinic journal of medicine 2002;69(11):909-17.</ref> | |||

== Physiotherapy management == | |||

=== [[Spondylolisthesis]] === | |||

<u><br></u>Spondylolisthesis should be treated first with conservative therapy, which includes physiotherapy, rest, medication and braces.<ref>Hu SS, Tribus CB, Diab M, Ghanayem AJ. [https://journals.lww.com/jbjsjournal/Citation/2008/03000/Spondylolisthesis_and_Spondylolysis.25.aspx Spondylolisthesis and spondylolysis.] JBJS 2008;90(3):656-71.</ref><ref name=":5">Kalpakcioglu B, Altınbilek T, Senel K. [https://content.iospress.com/articles/journal-of-back-and-musculoskeletal-rehabilitation/bmr00212 Determination of spondylolisthesis in low back pain by clinical evaluation.] Journal of Back and Musculoskeletal Rehabilitation 2009;22(1):27-32.</ref> Non-operative treatment should be the initial course of action in most cases of degenerative [[spondylolisthesis]] and symptomatic isthmic [[spondylolisthesis]], with or without neurologic symptoms.<ref name=":5" /><ref name=":6">Tang S. [https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4163248/ Treating traumatic lumbosacral spondylolisthesis using posterior lumbar interbody fusion with three years follow up.] Pakistan journal of medical sciences 2014;30(5):1137.</ref> Children or young adults with a high-grade dysplastic or isthmic [[spondylolisthesis]] or adults with any type of spondylolisthesis, who do not respond to non-operative care, should consider surgery. Traumatic [[spondylolisthesis]] can be treated successfully using conservative methods, but most authors suggested it would result in post-traumatic translational instability or chronic low back pain.<ref name=":6" /> Exercises should be done on a daily basis.<ref name=":5" /> | |||

< | === [[Scoliosis]] === | ||

Physiotherapy and bracing are used to treat milder forms of [[scoliosis]] to maintain cosmetic and avoid surgery.<ref>Harris JA, Mayer OH, Shah SA, Campbell RM, Balasubramanian S. [https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s00586-014-3580-8 A comprehensive review of thoracic deformity parameters in scoliosis.] European Spine Journal 2014;23(12):2594-602.</ref> [[Scoliosis]] is not just a lateral curvature of the spine, it’s a three-dimensional condition. To manage [[scoliosis]], we need to work in three planes: the sagittal, frontal and transverse. Different methods have already been studied.<ref>Scoliosis 3DC. Schroth Method for Scoliosis. Available from:https://scoliosis3dc.com/scoliosis-treatment-options/schroth-method-for-scoliosis/ (accessed 30/01/2020).</ref> The conservative therapy consists of: physical exercises, bracing, manipulation, electrical stimulation and insoles. There is still discussion about the fact that conservative therapy is effective or not. Some therapists follow the ‘wait and see’ method. This means that at one moment; the [[Cobb's angle|Cobb's degree]] threshold will be achieved. Then, the only possibility is a spinal surgery.<ref>Fusco C, Zaina F, Atanasio S, Romano M, Negrini A, Negrini S. [https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.3109/09593985.2010.533342 Physical exercises in the treatment of adolescent idiopathic scoliosis: an updated systematic review.] Physiotherapy theory and practice 2011;27(1):80-114.</ref><br> | |||

The | === [[Lumbar Radiculopathy|Lumbar radiculopathy]] === | ||

The more treatable condition of lumbar radiculopathy, however, arises when extruded disc material contacts, or exerts pressure, on the thecal sac or lumbar nerve roots.<ref>Schoenfeld AJ, Weiner BK. [https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2915533/ Treatment of lumbar disc herniation: evidence-based practice.] International journal of general medicine 2010;3:209.</ref> The literature support conservative management and surgical intervention as viable options for the treatment of radiculopathy caused by lumbar [[Disc Herniation|disc herniation]]. In the first place a conservative management is chosen. In a recent systematic review was found that a conservative treatment does not always provide for the disappearance of the symptoms of the patient.<ref>Vroomen PC, De Krom MC, Knottnerus JA. [https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s004150050480 Diagnostic value of history and physical examination in patients suspected of sciatica due to disc herniation: a systematic review.] Journal of neurology 1999;246(10):899-906.</ref> | |||

Providing information to the patient about the causes and prognosis can be a logical step in the management of lumbosacral radiculopathy, but there are no randomized, controlled studies.<ref name=":1" /> | |||

=== [[Cauda Equina Syndrome|Cauda equina syndrome]] === | |||

The ultimate goals of physical management are to ensure maximum neurological recovery and independence, a pain-free and flexible spine, maintenance of mobility and strength in lower limbs, of core strength, improvement of standing and walking function, improvement of bladder, bowel and sexual function, improvement of endurance and safe functioning of the various systems of the body with minimal or no inconvenience to patients and prevention or minimization of complications.<ref>Fraser S, Roberts L, Murphy E. [https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0003999309006479 Cauda equina syndrome: a literature review of its definition and clinical presentation.] Archives of physical medicine and rehabilitation 2009;90(11):1964-8.</ref> It is equally important for patients to regain assertiveness, take control of their own lives, and return to activities of their choice. The importance of ongoing support to maintain health and independence following discharge should be strongly emphasized.<ref name=":2" /><ref>El Masri WS. [https://pdfs.semanticscholar.org/63d0/7458e8baa1193a796535c9bd1ff0f5c149e9.pdf Management of traumatic spinal cord injuries: current standard of care revisited.] Adv Clin Neurosci Rehabil 2010;10(1):37-9.</ref> | |||

=== [[Scheuermanns Disease|Scheuermann's disease]] === | |||

Treatment of Scheuermann's disease depends on the severity or the progression of the disease, the presence or absence of pain and the age of the patient. Patients with a mild form are suggested to exercise and get a prescription from the doctor for physiotherapy. | Treatment of Scheuermann's disease depends on the severity or the progression of the disease, the presence or absence of pain and the age of the patient. Patients with a mild form are suggested to exercise and get a prescription from the doctor for physiotherapy. | ||

The methods of | The methods of physiotherapy include exercise programs to maintain flexibility of the back, correct lumbar lordosis, and strengthen the extensors of the back, electrostimulation and vertebral traction for increasing flexibility before a cast is applied.<ref name=":7">Axelrod T, Zhu F, Lomasney L, Wojewnik B. [https://www.healio.com/orthopedics/journals/ortho/2015-1-38-1/%7B0d9580ed-1193-4ff2-92eb-bb007a788b9d%7D/scheuermannrsquos-disease-dysostosis-of-the-spine Scheuermann’s Disease (Dysostosis) of the Spine.] Orthopedics 2015;38(1):4-71.</ref> Although physiotherapy has no role in correcting the underlying deformity, it is recommended in combination with bracing.<ref>Platero D, Luna JD, Pedraza V. [https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Jd_Luna/publication/13813983_Juvenile_kyphosis_Effects_of_different_variables_on_conservative_treatment_outcome/links/562f7a1a08aeb2ca6962148b.pdf Juvenile kyphosis: effects of different variables on conservative treatment outcome.] Acta orthopaedica belgica 1997;63:194-201.</ref> | ||

=== Lumbar Spinal Stenosis === | |||

[[Lumbar Spinal Stenosis]] patients frequently receive early surgical treatment, although conservative treatment can be a viable option. Not only because of the complications that can arise from surgery, but also because mild symptoms of radicular pain often can be lightened with physiotherapy.<ref>Minamide A, Yoshida M, Maio K. [https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s00776-013-0435-9 The natural clinical course of lumbar spinal stenosis: a longitudinal cohort study over a minimum of 10 years.] Journal of Orthopaedic Science 2013;18(5):693-8.</ref> However, in patients with severe [[Lumbar Spinal Stenosis]], surgery overall seems to be a better option than conservative interventions such as injections and rehabilitation. Still, its specific content and effectiveness relative to other non-surgical strategies has not been clarified yet.<ref name=":8">May S, Comer C. [https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0031940612000272 Is surgery more effective than non-surgical treatment for spinal stenosis, and which non-surgical treatment is more effective? A systematic review.] Physiotherapy 2013;99(1):12-20.</ref> Post-operative care after spinal surgery is variable, with major differences reported between surgeons in the type and intensity of rehabilitation provided and in restrictions imposed and advice offered to participants. Post-operative management may include education, rehabilitation, exercise, behavioral graded training, neuromuscular training and stabilization training.<ref>McGregor AH, Probyn K, Cro S, Doré CJ, Burton AK, Balagué F, Pincus T, Fairbank J. [https://cdn.journals.lww.com/spinejournal/Abstract/2014/06010/Rehabilitation_Following_Surgery_for_Lumbar_Spinal.14.aspx Rehabilitation following surgery for lumbar spinal stenosis: a Cochrane review.] Spine 2014;39(13):1044-54.</ref> Numerous physiotherapy interventions have been recommended for patients with [[Lumbar Spinal Stenosis]], suggesting a role for general conditioning using body weight–supported treadmill walking or stationary cycling, strengthening exercises for the trunk and lower extremities, and manual therapy for the spine and [[Hip Anatomy|hips]].<ref name=":8" /> | |||

== Clinical bottom line == | |||

* Physiotherapists must screen for these serious pathologies and specific conditions that lead to neurological deficit in the assessment of an individual with low back pain to direct appropriate management. | |||

* Physiotherapy has a beneficial effect in the treatment of specific [[Low Back Pain|low back pain]], when it’s part of a treatment program. Goals of the rehabilitation, non-operative and post-operative, are reducing pain and muscle tension, strengthen the stabilizing muscles and regain proprioception, neurological recovery and movement automatism. Physiotherapy consists of passive and active mobilization and strengthening exercises. | |||

* 90% of people will have no clear pathoanatomical diagnosis and an absence of [[Red Flags in Spinal Conditions|red flags]], these people have non-specific [[Low Back Pain|low back pain]]. | |||

90% of people will have no clear pathoanatomical diagnosis and an absence of red flags, these people have non-specific | |||

== References == | == References == | ||

[[Category:Lumbar Spine]] | [[Category:Lumbar Spine]] | ||

Latest revision as of 11:21, 28 August 2023

Top Contributors -

Introduction[edit | edit source]

Low back pain is a considerable health problem in all developed countries and is most commonly treated in primary healthcare settings. It is usually defined as pain, muscle tension, or stiffness localised below the costal margin and above the inferior gluteal folds, with or without leg pain (sciatica). The most important symptoms of low back pain are pain and disability..

About 90% of all patients with low back pain will have non-specific low back pain, which, in essence, is a diagnosis based on exclusion of specific pathology.[1] Those specific pathologies can be defined as:

- Radiculopathy

- Disc herniation

- Lumbar Spinal Stenosis

- Spondylolisthesis

- Ankylosing spondylitis

- Osteoporosis

- Lumbar spine fracture

- Skeletal metastases

- Cauda equina syndrome

- Scheuermans disease

- Scoliosis

Clinically relevant anatomy[edit | edit source]

The human spine is a self-supporting construction of skeleton, cartilage, ligaments and muscles. The lower back (where most back pain occurs) includes the five vertebrae in the lumbar region and supports much of the weight of the upper body. The spaces between the vertebrae are maintained by intervertebral discs that act like shock absorbers throughout the spinal column to cushion the bones as the body moves. Ligaments hold the vertebrae in place, and tendons attach the muscles to the spinal column. Thirty-one pairs of nerves are rooted to the spinal cord and they control body movements and transmit signals from the body to the brain.

See lumbar anatomy for more information.

Epidemiology/Etiology[edit | edit source]

Low back pain is a symptom, not a disease, and has many causes. It is generally described as pain between the costal margin and the gluteal folds. It is extremely common. About 40% of people report having had low back pain within the past 6 months. Onset usually begins in the teens to early 40s. A small percentage of low back pain becomes chronic.[2][3] Low back pain is considered acute if its onset occurred less than 1 month ago. The symptoms of chronic low back pain have lasted 2 months or longer. Both acute and chronic low back pain may be further classified as non-specific or specific/radicular.[4]

Characteristics/ Clinical Presentation[edit | edit source]

Scoliosis[5][edit | edit source]

- Not much pain

- Sideways curvature of the spine

- Muscle strains

- Antalgic posture

- Sideways body posture

- One shoulder raised higher than the other

- Local muscular aches

- Local ligament pain

Scheuermann's disease[6][7][8][edit | edit source]

- History of deformity because of structural kyphosis in adolescence

- In the lumbar spine, hyper-lordosis can occur

- Strong correlation between Scheuermann’s disease and scoliosis

- Hamstring tightness

- Back pain, located distal to the apex of the deformity

- Activity related to pain

- Fatigue

- Muscle stiffness (especially at the end of the day)

- Neurological symptoms

- In severe cases: Heart and lung function can be impaired. Other secondary changes are Schmorl nodes, irregular vertebral endplates and dics space narrowing

- Muscle spasms or muscle cramps

- Difficulty exercising

- Limited flexibility

Ankylosing spondylitis[9][10] [edit | edit source]

5 phases

- Acute inflammation

- Damage to the cartilage because of repeatedly acute inflammations

- Damaged cartilage does not heal and is replaced by bone tissue

- Joint loses his flexibility

- Components of the joint grow towards each other and form 1 piece

Important symptoms

- Iridocyclitis or uveïtis (inflammation of the iris)

- Nerve pain in the chest, abdomen of legs

- Morning stiffness lasting greater than 30 minutes and waking up in the second half of the night

- Pain and stiffness increase with inactivity and improve with exercise

- Respiratory complaints

- Inflammation of achilles tendons

- Psoriasis (skin condition)

- Intestinal problems (Crohn's Disease)

- Peripheral joints, eyes, skin and the cardiac and intestinal systems problems

- The hips, shoulder and knees are the most commonly and most severely affected of the extremity joints

- Complaints of intermittent breathing difficulties because of a decrease in chest expansion

- Also fatigue, weight loss and fever are indirect effects of inflammation processes. This can lead to severe psychological issues such as depression.

Disc herniation[11] [edit | edit source]

Herniated disc not pressing on the nerve:

- No pain

Herniated disc pressing on the nerve(s):

- Stiffness

- Sharp pain

- Tingling and weakness

- Referred pain in legs

- Paralysis

The severity of the complaints depends on the strength of compressive from the hernia on surrounding components.

Radicular syndrome[12][13][edit | edit source]

- Sharp, dull, piercing, throbbing, stabbing, shooting or burning pain

- Numbness, tingling and weakness in the arms or legs

- Radicular pain in one leg

- Neurological loss of function

- Unilateral pain radiating to foot or toes

- Numbness and paraesthesia in the same distribution

- Paravertebral pressure above the nerve root causes pain in the periphery

- Failure of the sensible dermatome

- Nerve root entrapment such as sensory deficits, reflex changes or muscle weakness

Spinal canal stenosis[14][15][16][edit | edit source]

- Persisting and heavy pain in the low back

- Referred pain in legs

- Symptoms increase when standing straight

- Laying down/sitting down/bending forward decreases the pain

- Areas off the body who are not in pain, can feel itchy and inflamed

- Muscle tension in spine

- Sensibility disorders

- Sleeping disorders

- Incontinence problems

- Sexual dysfunctions

- Immobility of low back

- Pain and/or weakness in legs and buttocks

- Neurogenic intermittent claudication

Spondylolisthesis[17][edit | edit source]

- Instability

- Stiffness in lower back

- Pain with extension

- Referred pain in upper leg

- Immobility low back

- Resting decreases pain

- Trophic changes

- Atrophy of the muscles

- Tense hamstrings

- Disturbance in patterns

- Diminished spinal range of motion

- Disturbances in coordination and balance

- Neurological symptoms (possible evolution towards cauda equina syndrome)

Metastases[18][edit | edit source]

- Pain increases at night and in rest

- Paralysis

- Compression on the spinal cord resulting in numbness or tingling in the abdomen and legs, bowel and bladder problems, difficulty walking

Cauda equina syndrome (CES)[19][edit | edit source]

- Difficulties to urinate

- Decrease of sensibility in legs

- Low back pain

- Referred pain in legs

- Sensibility disorders of genital organs

- Difficulty walking

Differential Diagnosis[edit | edit source]

Some conditions can present with similar impairments and should be included in the clinician’s differential diagnosis:

Mechanical

- Lumbar muscular strain/sprain

Systemic

Referred

Diagnostic procedures[edit | edit source]

In clinical practice, the triage is focused on identification of “red flags” (see box 1/2) as indicators of possible underlying pathology, including nerve root problems. When red flags are not present, the patient is considered as having non-specific low back pain. Besides those red flags there are yellow flags. “Yellow flags” have been developed for the identification of patients at risk of chronic pain and disability. A screening instrument based on these yellow flags has been validated for use in clinical practice.[18] The predictive value of the yellow flags and the screening instrument need to be further evaluated in clinical practice and research.

Abnormalities in x-ray and magnetic resonance imaging and the occurrence of non-specific low back pain seem not to be strongly associated.[19] Abnormalities found when imaging people without back pain are just as prevalent as those found in patients with back pain. Van Tulder and Roland reported radiological abnormalities varying from 40% to 50% for degeneration and spondylosis in people without low back pain. They reported that radiologists should include this epidemiological data when reporting the findings of a radiological investigation.[20] Many people with low back pain show no abnormalities. In clinical guidelines these findings have led to the recommendation to be restrictive in referral for imaging in patients with non-specific low back pain. Only in cases with red flag conditions might imaging be indicated. Jarvik et al reported that computed tomography and magnetic resonance imaging are equally accurate for diagnosing lumbar disc herniation and stenosis — both conditions that can easily be separated from non-specific low back pain by the appearance of red flags. Magnetic resonance imaging is probably more accurate than other types of imaging for diagnosing infections and malignancies,[21] but the prevalence of these specific pathologies is low.

Outcome measures[edit | edit source]

The following list contains commonly used low back pain outcome measures. These questionnaires are complete and not patient specific. Often medical imaging has to be done to include specific low back pain disorders,but your own clinical judgement will be necessary to determine the most useful measure in your clinical setting.

- Quebec Back Pain Disability Scale

- A condition–specific questionnaire developed to measure the level of functional disability for patients with low back pain. Intended for those who suffer diseases such as acute low back pain, chronic pain, Lumbar Spinal Stenosis, posterior surgical decompression.

- Oswestry Disability Index

- Patient-completed questionnaire which gives a subjective percentage of level of function (disability) in activities of daily living in those during rehabilitation from low back pain in acute or chronic low back pain.

- Roland-Morris Disability Questionnaire

- The patient is asked to tick off different statements when it is applied to him, that specific time. It is most sensitive for patients with mild to moderate disability.

- Back Pain Functional Scale

- A 12-item self-report measure that evaluates functional ability that is intended for people who are suffering from back pain.

Examination[edit | edit source]

The first aim of the physiotherapy examination for a patient presenting with back pain is to classify the patient according to the diagnostic triage recommended in international back pain guidelines. Serious and specific causes of back pain with neurological deficits are rare but it is important to screen for these conditions. Serious conditions account for 1-2% of people presenting with low back pain. When serious and specific causes of low back pain have been ruled out individuals are said to have non-specific (or simple or mechanical) back pain.

The examination consists of:

Observation[edit | edit source]

- How does the patient enter the room?

- A posture deformity in flexion or a deformity with a lateral pelvic tilt, possibly a slight limp, may be seen.

- How does the patient sit down and how comfortably/uncomfortably does he or she sit?

- How does the patient get up from the chair? A patient with low back pain may splint the spine in order to avoid painful movements.

- Posture: look out for scoliosis (Adam's forward bend test), excessive lordosis or kyphosis.

Other observations[edit | edit source]

- Body type

- Attitude

- Facial expression

- Skin

- Hair

- Leg length discrepancy (functional vs structural)

Range of motion[edit | edit source]

Active range of motion of the lumbar spine is evaluated with the patient standing. Motion of the lumbar spine occurs in 3 planes and includes 4 directions, as follows:

- Forward flexion: 40°-60°

- Extension: 20°-35°

- Lateral flexion/side bending (left and right): 15°-20°

- Rotation (left and right): 3°-18°

Isometric muscle testing[edit | edit source]

Strength testing of the lumbar spine includes the muscles around the spine column and the large moving muscles that attach onto the axial skeleton. The goal of muscle testing is to evaluate for strength and reproduction of pain.

Palpation[edit | edit source]

The physician can use palpation for two purposes during examination of the lumbar spine:

- To help locate tender areas

- To confirm findings previously demonstrated in the examination

Test for neurological dysfunction[edit | edit source]

The straight leg raise test is used to evaluate for lumbar nerve root impingement or irritation. This is a passive test in which each leg is examined individually.

- Sensitivity of 35%-97%

- Specificity of 10%-100%

The Slump test is used to evaluate for lumbar nerve root impingement or irritation. A positive Slump test result is demonstrated with the reproduction of radicular symptoms. The test is then repeated on the contralateral side.

- Sensitivity of 44%-84%

- Specificity of 58%-83%

{{#ev:youtube|8Qknf8yyMFQ|300}}

Femoral Nerve Tension Test:

The femoral nerve traction test is used to evaluate for pathology of the femoral nerve or nerve routes coming out of the third and fourth lumbar segments.

6. Tests for Joint Dysfunction

The one leg stand test, or stork stand test, is used to evaluate for pars interarticularis stress fracture (spondylolysis).

- Sensitivity of 50%-55%

- Specificity of 46%-68%

FABER Test (flexion abduction external rotation test):

The flexion, abduction, external rotation (FABER) test is used to evaluate for pathology of the Sacroiliac Joint.

- Sensitivity of 54%-66%

- Specificity of 51%-62%

This test is used to determine if the hip is the source of the patient's symptoms. A positive test is a reproduction of the patient's worst pain that they came with into the clinic.

- Sensitivity: 75%

- Specificity: 43%- 58%

Medical management[edit | edit source]

Spondylolisthesis[edit | edit source]

- Initially resting and avoiding movements like lifting, bending and sports.

- Analgesics and non-steroidal anti-inflammatories reduce musculoskeletal pain and have an anti-inflammatory effect on nerve root and joint irritation.

- Epidural steroid injections can be used to relieve low back pain, lower extremity pain related to radiculopathy and neurogenic claudication.

- A brace may be useful to decrease segmental spinal instability and pain.[24]

Surgery

Patients with chronic and disabling symptoms, who fail to respond to conservative management may be referred for surgery.[25]

Scoliosis[edit | edit source]

Patients with early-onset scoliosis, defined as a lateral curvature of the spine under the age of 10 years, are offered surgical treatment when the major curvature remains progressive despite conservative treatment (Cobb's angle 50° or more). Spinal fusion is not recommended in this age group, as it prevents spinal growth and pulmonary development.[26]

Conservative treatment: In conservative treatment, the use of braces mainly aims to prevent the progression of secondary curves that develop above and below the congenital curve, causing imbalance. In these cases, they may be applied until skeletal maturity.[26]

Surgical treatment: Spinal surgery in patients with congenital scoliosis is regarded as a safe procedure and many authors claim that surgery should be performed as early as possible to prevent the development of severe local deformities and secondary structural deformities that would require more extensive fusion later. Most of the time surgery is performed during adolescence, but newer techniques allow good correction to be accomplished into early adulthood. The goals for surgical treatment are to prevent progression and to improve spinal alignment and balance.[26]

Radicular Syndrome[edit | edit source]

Lumbar radicular syndrome can be treated in a conservative or a surgical way. The international consensus says that in the first 6-8 weeks, conservative treatment is indicated.[27] Surgery should be offered only if complaints remain present for at least 6 weeks after a conservative treatment.[28] A surgical intervention for sciatica is called a discectomy and focuses on removal of disc herniation and eventually a part of the disc.[29] See the page for lumbar radiculopathy for further information

Cauda Equina Syndrome[edit | edit source]

Once cauda equina syndrome is diagnosed, emergent surgical decompression is recommended to avoid potential permanent neurological damage.[30] The role of surgery is to relieve pressure from the nerves in the cauda equina region and to remove the offending elements.[31]

Scheuermann's disease[edit | edit source]

The treatment of Scheuermann’s disease depends on the patient’s age, degree of angulation, and estimated remaining growth.

Non-operative treatment

If the thoracic kyphosis exceeds 40-45° during the growth period and if there are radiological signs of Scheuermann’s disease, non-operative treatment is indicated. This consists of bracing, casting and exercises.[6]

Operative treatment

Patients with Scheuermann’s disease rarely undergo surgery because the natural history of the disease is in most cases benign. Conservative treatment is usually not effective for large curves (above 75°) or in the adult. Spinal pain and unacceptable cosmetic appearance are the most common indications for surgery. It’s important to be careful in counselling these patients because these criteria are subjective. As a result of this, there are also no evidence-based criteria for an indication of surgery.[6][32][33]

Lumbar Spinal Stenosis[edit | edit source]

If non-operative treatment has failed, surgical treatment may be considered. The key in deciding whether or not to have surgery is the degree of physical disability and disabling pain. In most cases of advanced claudication (spinal or vascular), a decompression surgery is required to alleviate the symptoms of spinal stenosis.[34]

Steroid injections and non-steroidal inflammatory medications can also be used to treat lumbar spinal stenosis.[34][35]

Physiotherapy management[edit | edit source]

Spondylolisthesis[edit | edit source]

Spondylolisthesis should be treated first with conservative therapy, which includes physiotherapy, rest, medication and braces.[36][37] Non-operative treatment should be the initial course of action in most cases of degenerative spondylolisthesis and symptomatic isthmic spondylolisthesis, with or without neurologic symptoms.[37][38] Children or young adults with a high-grade dysplastic or isthmic spondylolisthesis or adults with any type of spondylolisthesis, who do not respond to non-operative care, should consider surgery. Traumatic spondylolisthesis can be treated successfully using conservative methods, but most authors suggested it would result in post-traumatic translational instability or chronic low back pain.[38] Exercises should be done on a daily basis.[37]

Scoliosis[edit | edit source]

Physiotherapy and bracing are used to treat milder forms of scoliosis to maintain cosmetic and avoid surgery.[39] Scoliosis is not just a lateral curvature of the spine, it’s a three-dimensional condition. To manage scoliosis, we need to work in three planes: the sagittal, frontal and transverse. Different methods have already been studied.[40] The conservative therapy consists of: physical exercises, bracing, manipulation, electrical stimulation and insoles. There is still discussion about the fact that conservative therapy is effective or not. Some therapists follow the ‘wait and see’ method. This means that at one moment; the Cobb's degree threshold will be achieved. Then, the only possibility is a spinal surgery.[41]

Lumbar radiculopathy[edit | edit source]

The more treatable condition of lumbar radiculopathy, however, arises when extruded disc material contacts, or exerts pressure, on the thecal sac or lumbar nerve roots.[42] The literature support conservative management and surgical intervention as viable options for the treatment of radiculopathy caused by lumbar disc herniation. In the first place a conservative management is chosen. In a recent systematic review was found that a conservative treatment does not always provide for the disappearance of the symptoms of the patient.[43]

Providing information to the patient about the causes and prognosis can be a logical step in the management of lumbosacral radiculopathy, but there are no randomized, controlled studies.[29]

Cauda equina syndrome[edit | edit source]

The ultimate goals of physical management are to ensure maximum neurological recovery and independence, a pain-free and flexible spine, maintenance of mobility and strength in lower limbs, of core strength, improvement of standing and walking function, improvement of bladder, bowel and sexual function, improvement of endurance and safe functioning of the various systems of the body with minimal or no inconvenience to patients and prevention or minimization of complications.[44] It is equally important for patients to regain assertiveness, take control of their own lives, and return to activities of their choice. The importance of ongoing support to maintain health and independence following discharge should be strongly emphasized.[31][45]

Scheuermann's disease[edit | edit source]

Treatment of Scheuermann's disease depends on the severity or the progression of the disease, the presence or absence of pain and the age of the patient. Patients with a mild form are suggested to exercise and get a prescription from the doctor for physiotherapy.

The methods of physiotherapy include exercise programs to maintain flexibility of the back, correct lumbar lordosis, and strengthen the extensors of the back, electrostimulation and vertebral traction for increasing flexibility before a cast is applied.[8] Although physiotherapy has no role in correcting the underlying deformity, it is recommended in combination with bracing.[46]

Lumbar Spinal Stenosis[edit | edit source]

Lumbar Spinal Stenosis patients frequently receive early surgical treatment, although conservative treatment can be a viable option. Not only because of the complications that can arise from surgery, but also because mild symptoms of radicular pain often can be lightened with physiotherapy.[47] However, in patients with severe Lumbar Spinal Stenosis, surgery overall seems to be a better option than conservative interventions such as injections and rehabilitation. Still, its specific content and effectiveness relative to other non-surgical strategies has not been clarified yet.[48] Post-operative care after spinal surgery is variable, with major differences reported between surgeons in the type and intensity of rehabilitation provided and in restrictions imposed and advice offered to participants. Post-operative management may include education, rehabilitation, exercise, behavioral graded training, neuromuscular training and stabilization training.[49] Numerous physiotherapy interventions have been recommended for patients with Lumbar Spinal Stenosis, suggesting a role for general conditioning using body weight–supported treadmill walking or stationary cycling, strengthening exercises for the trunk and lower extremities, and manual therapy for the spine and hips.[48]

Clinical bottom line[edit | edit source]

- Physiotherapists must screen for these serious pathologies and specific conditions that lead to neurological deficit in the assessment of an individual with low back pain to direct appropriate management.

- Physiotherapy has a beneficial effect in the treatment of specific low back pain, when it’s part of a treatment program. Goals of the rehabilitation, non-operative and post-operative, are reducing pain and muscle tension, strengthen the stabilizing muscles and regain proprioception, neurological recovery and movement automatism. Physiotherapy consists of passive and active mobilization and strengthening exercises.

- 90% of people will have no clear pathoanatomical diagnosis and an absence of red flags, these people have non-specific low back pain.

References[edit | edit source]

- ↑ Koes BW, Van Tulder MW. Clinical Review, Diagnosis and treatment of low back pain. BMJ 2006;332:1430

- ↑ Randall L. Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation. 4th edition. Elseiver 2002. p871

- ↑ Hoy D, Brooks P, Blyth F, Buchbinder R. The epidemiology of low back pain. Best practice & research Clinical rheumatology 2010;24(6):769-81.

- ↑ Majid K, Truumees E. Epidemiology and natural history of low back pain. Seminars in Spine Surgery 2008;20(2):87-92.

- ↑ Johari J, Sharifudin MA, Ab Rahman A, Omar AS, Abdullah AT, Nor S, Lam WC, Yusof MI. Relationship between pulmonary function and degree of spinal deformity, location of apical vertebrae and age among adolescent idiopathic scoliosis patients. Singapore medical journal 2016;57(1):33.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 Wenger DR, Frick SL. Scheuermann kyphosis. Spine 1999;24(24):2630.

- ↑ Ristolainen L, Kettunen JA, Heliövaara M, Kujala UM, Heinonen A, Schlenzka D. Untreated Scheuermann’s disease: a 37-year follow-up study. European Spine Journal 2012;21(5):819-24.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 Axelrod T, Zhu F, Lomasney L, Wojewnik B. Scheuermann’s Disease (Dysostosis) of the Spine. Orthopedics 2015;38(1):4-71.

- ↑ Andersson BJG, Thomas W. McNeill. Lumbar Spine Syndromes: Evaluation and Treatment. Springer-Verlag, 1989.

- ↑ Baaj AA, Mummaneni PV, Uribe JS, Vaccaro AR, Greenberg MS. Handbook of Spine Surgery. 1st Edition. New York: Thieme, 2012.

- ↑ American Association of Neurological Surgeons. Herniated disc. Available from: https://www.aans.org/Patients/Neurosurgical-Conditions-and-Treatments/Herniated-Disc (accessed 01/02/2020).

- ↑ Konstantinou K, Dunn KM, Ogollah R, Vogel S, Hay EM. Characteristics of patients with low back and leg pain seeking treatment in primary care: baseline results from the ATLAS cohort study. BMC musculoskeletal disorders 2015;16(1):332.

- ↑ Van Boxem K, Cheng J, Patijn J, Van Kleef M, Lataster A, Mekhail N, Van Zundert J. Lumbosacral radicular pain. Pain Practice 2010;10(4):339-58.

- ↑ Siebert E, Prüss H, Klingebiel R, Failli V, Einhäupl KM, Schwab JM. Lumbar spinal stenosis: syndrome, diagnostics and treatment. Neurology 2009;5(7):392-403.

- ↑ Spine-health. What is Spinal Stenosis? Available from: http://www.spine-health.com/conditions/spinal-stenosis/what-spinal-stenosis (accessed 01/02/2020).

- ↑ Kraus Back and Neck Institute. Stenosis – Pain and other symptoms. Available from: http://www.spinesurgery.com/conditions/stenosis (accessed 01/02/2020).

- ↑ Wicker A. Spondylolysis and spondylolisthesis in sports: FIMS Position Statement. International Sport Med Journal 2008;9(2):74-8.

- ↑ 18.0 18.1 Linton SJ, Halldén K. Can we screen for problematic back pain? A screening questionnaire for predicting outcome in acute and subacute back pain. The Clinical journal of pain 1998;14(3):209-15.

- ↑ 19.0 19.1 Van Tulder MW, Assendelft WJ, Koes BW, Bouter LM. Spinal radiographic findings and nonspecific low back pain. A systematic review of observational studies. Spine 1997;22:427-34.

- ↑ Roland M, Van Tulder M. Should radiologists change the way they report plain radiography of the spine? Lancet 1998;352:348-9.

- ↑ Jarvik JG, Deyo RA. Diagnostic evaluation of low back pain with emphasis on imaging. Ann Int Med 2002;137:586-97.

- ↑ Kalichman L, Hunter DJ. Diagnosis and conservative management of degenerative lumbar spondylolisthesis. European Spine Journal 2008;17(3):327-35.

- ↑ Weinstein JN, Tosteson TD, Lurie JD, Tosteson AN, Blood E, Hanscom B, Herkowitz H, Cammisa F, Albert T, Boden SD, Hilibrand A. Surgical versus nonsurgical therapy for lumbar spinal stenosis. New England Journal of Medicine 2008;358(8):794-810.

- ↑ Belfi LM, Ortiz AO, Katz DS. Computed tomography evaluation of spondylolysis and spondylolisthesis in asymptomatic patients. Spine 2006;31(24):E907-10.

- ↑ Monticone M, Ferrante S, Teli M, Rocca B, Foti C, Lovi A, Bruno MB. Management of catastrophising and kinesiophobia improves rehabilitation after fusion for lumbar spondylolisthesis and stenosis. A randomised controlled trial. European spine journal 2014;23(1):87-95.

- ↑ 26.0 26.1 26.2 Kaspiris A, Grivas TB, Weiss HR, Turnbull D. Surgical and conservative treatment of patients with congenital scoliosis: α search for long-term results. Scoliosis 2011;6(1):12.

- ↑ Driscoll T, Sambrook PN. Best Practice and Research: Clinical Rheumatology. Best Practice and Research: Clinical Rheumatology 2011;25(1):1-2.

- ↑ Jacobs WC, van Tulder M, Arts M, Rubinstein SM, van Middelkoop M, Ostelo R, Verhagen A, Koes B, Peul WC. Surgery versus conservative management of sciatica due to a lumbar herniated disc: a systematic review. European Spine Journal 2011;20(4):513-22.

- ↑ 29.0 29.1 Koes BW, Van Tulder MW, Peul WC. Diagnosis and treatment of sciatica. Bmj 2007;334(7607):1313-7.

- ↑ Bin MA, Hong WU, Jia LS, Wen YU, Shi GD, Shi JG. Cauda equina syndrome: a review of clinical progress. Chinese medical journal 2009;122(10):1214-22.

- ↑ 31.0 31.1 Gardner A, Gardner E, Morley T. Cauda equina syndrome: a review of the current clinical and medico-legal position. European Spine Journal 2011;20(5):690-7.

- ↑ Etemadifar M, Ebrahimzadeh A, Hadi A, Feizi M. Comparison of Scheuermann’s kyphosis correction by combined anterior–posterior fusion versus posterior-only procedure. European Spine Journal 2016;25(8):2580-6.

- ↑ Yanik HS, Ketenci IE, Coskun T, Ulusoy A, Erdem S. Selection of distal fusion level in posterior instrumentation and fusion of Scheuermann kyphosis: is fusion to sagittal stable vertebra necessary?. European Spine Journal 2016;25(2):583-9.

- ↑ 34.0 34.1 Costa LO, Maher CG, Latimer J. Self-report outcome measures for low back pain: searching for international cross-cultural adaptations. Spine 2007;32(9):1028-37.

- ↑ Mazanec DJ, Podichetty VK, Hsia A. Lumbar canal stenosis: start with nonsurgical therapy. Cleveland Clinic journal of medicine 2002;69(11):909-17.

- ↑ Hu SS, Tribus CB, Diab M, Ghanayem AJ. Spondylolisthesis and spondylolysis. JBJS 2008;90(3):656-71.

- ↑ 37.0 37.1 37.2 Kalpakcioglu B, Altınbilek T, Senel K. Determination of spondylolisthesis in low back pain by clinical evaluation. Journal of Back and Musculoskeletal Rehabilitation 2009;22(1):27-32.