Spondylolisthesis

Original Editor - Margo De Mesmaeker

Top Contributors - Maëlle Cormond, Simisola Ajeyalemi, Evi Peeters, Margo De Mesmaeker, Kim Jackson, Admin, Chrysolite Jyothi Kommu, Kenneth de Becker, Shaimaa Eldib, Lucinda hampton, Mike Myracle, Rachael Lowe, Evan Thomas, Johnathan Fahrner, Aminat Abolade, Mariam Hashem, Carlos De Coster, Shreya Pavaskar, Camille Linussio, Kirenga Bamurange Liliane, Scott Buxton, Claire Knott, Rucha Gadgil, Laura Ritchie and Jess BellDefinition/Description[edit | edit source]

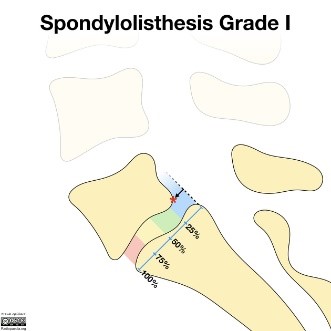

Spondylolisthesis is the slippage of one vertebral body with respect to the adjacent vertebral body causing mechanical or radicular symptoms or pain. It can be due to congenital, acquired, or idiopathic causes. Spondylolisthesis is graded based on the degree of slippage (Meyerding Classification) of one vertebral body on the adjacent vertebral body.[1]

Clinical Anatomy[edit | edit source]

Spondylolisthesis most commonly occurs in the lower lumbar spine but can also occur in the cervical spine and rarely, except for trauma, in the thoracic spine.[1]

Spondylolisthesis, regardless of the type, is mostly common preceded by spondylolysis. This pathology involves

- A fractured pars interarticularis of the lumbar vertebrae, also called the isthmus.

- This affects the supporting structural integrity of the vertebrae, which could lead to slippage of the corpus of the vertebrae, called spondylolysthesis.

- In turn, leads to one of the most obvious manifestations of lumbar instability.

- Slippage can occur in 2 directions- most commonly in anterior translation, called anterolisthesis, or a backward translation, called retrolisthesis.[2]

A study of Dai L.Y. analysed the correlation between disc degeneration and the age, duration and severity of clinical symptoms and grade of vertebral slip. The disc degeneration on sub segmental level was significantly related to age and duration of clinical symptoms, although it was not related to the severity of clinical symptoms or the grade of vertebral slip[3].

Epidemiology[edit | edit source]

- Degenerative spondylolisthesis predominately occurs in adults and is more common in females than males with increased risk in the obese.

- Isthmic spondylolisthesis is more common in the adolescent and young adult population but may go unrecognized until symptoms develop in adulthood. There is a higher prevalence of isthmic spondylolisthesis in males.

- Dysplastic spondylolisthesis is more common in the pediatric population, with females more commonly affected than males. Current estimates for prevalence are 6 to 7% for isthmic spondylolisthesis by the age of 18 years, and up to 18% of adult patients undergoing MRI of the lumbar spine.

- Grade I spondylolisthesis accounts for 75% of all cases.

- Spondylolisthesis most commonly occurs at the L5-S1 level with anterior translation of the L5 vertebral body on the S1 vertebral body.

- The L4-5 level is the second most common location for spondylolisthesis.[1]

Etiology[edit | edit source]

- Repetitive stress to the pars interarticularis

- Decreased strength of the neural arch at a young age predisposes children and adolescents to a higher risk of fracture.

- Traumatic accidental injuries

- Microtrauma in sports

- Pathological causes - Neoplasm, connective tissue disease, etc.

- Iatrogenic - After laminectomy

- Adolescents and children also have more elastic intervertebral disks which cause increased stress to be placed on the pars interarticularis

Classification[edit | edit source]

There are different classification systems regarding the etiology, terminology, subtypes of spondylolysis and spondylolisthesis, and treatment.

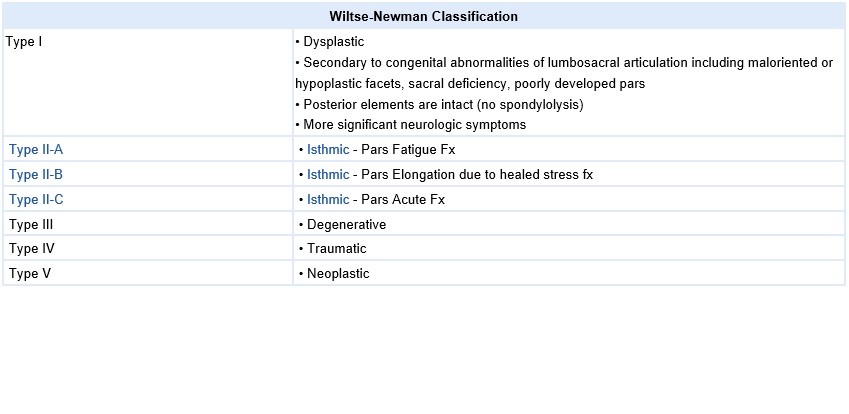

A. Wiltse Classification [4] is one of the most commonly used classification systems to convey the etiology of spondylolisthesis (see table below). It has five major etiologies: degenerative, isthmic, traumatic, dysplastic, or pathologic.

- Dysplastic spondylolisthesis (Type 1) is congenital and secondary to variation in the orientation of the facet joints to an abnormal alignment. In dysplastic spondylolisthesis, the facet joints are more sagittally oriented than the typical coronal orientation.

- Isthmic spondylolisthesis results from defects in the pars interarticularis. The cause of isthmic spondylolisthesis is undetermined, but a possible etiology includes microtrauma in adolescence related to sports such as wrestling, football, and gymnastics, where repeated lumbar extension occurs. Type II is isthmic and is separated into Type IIA and Type IIB. Type IIA is caused by a stress fracture of the pars interarticularis (spondylolysis) that results in anterior slippage of the vertebrae. Type II B is caused by repetitive fractures and subsequent healing which results in lengthening of the pars interarticularis leading to anterior slippage of the vertebrae.[4]

- Degenerative spondylolisthesis (Type 3) occurs from degenerative changes in the spine without any defect in the pars interarticularis. It is usually related to combined facet joint and disc degeneration leading to instability and forward movement of one vertebral body relative to the adjacent vertebral body. Arthritis of facet joint which in turn causes weakness of ligamentum flavum leads to anterior slippage of vertebra.

- Traumatic spondylolisthesis (Type 4)occurs after fractures of the pars interarticularis or the facet joint structure and is most common after trauma.

- Pathologic spondylolisthesis (Type 5) can be from systemic causes such as bone or connective tissue disorders or a focal process, including infection, neoplasm.

- Iatrogenic spondylolisthesis (Type 6) is a potential sequela of spinal surgery. Frequently, these patients will have undergone prior laminectomy

Additional risk factors for spondylolisthesis include a first-degree relative with spondylolisthesis, scoliosis, or Spina Bifida at the S1 level[1]

The Myerding classification defines the amount of vertebral slippage on X-ray in reference to the caudal vertebrae.4 There are five grades of spondylolisthesis in the Myerding classification. Grade I is less than 25 percent slippage, grade II is 26–50% slippage, grade III is 51–75% slippage, grade IV is 76–100% slippage, and grade V is over 100% slippage and is referred to as spondyloptosis[4].

Clinical Presentation[edit | edit source]

Symptoms and findings in spondylolisthesis [6]

- Patients typically have low back pain which mimics radiculopathy for lumbar spondylolisthesis and localized/radiating neck pain for cervical spondylolisthesis.

- Pain is exacerbated by extending at the affected segment, as this can cause mechanic pain from motion, leading to diminished ROM (spine). Pain decreases as the patient assumes flexed posture which reduces stress on the nerve being impinged.

- Pain may be exacerbated by direct palpation of the affected segment.

- Pain can also be radicular in nature as the exiting nerve roots become compressed due to the narrowing of nerve foramina as one vertebra slips on the adjacent vertebrae, the traversing nerve root (root to the level below) can also be impinged through associated lateral recess narrowing, disc protrusion, or central canal stenosis.

- Pain can sometimes improve in certain positions such as lying supine. This improvement is due to the instability of the spondylolisthesis that reduces with supine posture, thus relieving the pressure on the bony elements as well as opening the spinal canal or neural foramen.

- Spondylolisthesis can also present as an acute or acute-onchronic episode with the patient having severe exacerbation of pre-existing back pain, neurological deficits, hamstrings spasm and a crouched gait.[7]The patient develops a crouched gait (Phalen-Dickson sign) due to the vertical position of the sacrum, lumbosacral kyphosis, compensatory lordosis of the proximal spine and flexion of the knees and hips, which may be present regardless of the degree of slippage.

- Atrophy of the muscles, muscle weakness

- Tense hamstrings, hamstrings spasms

- Disturbances in coordination and balance, difficulty walking

- Rarely loss of bowel or bladder control.[1]

Spondylolisthesis can occur with other disorders and seems to have a link with some of them

- Spina Bifida [8] [9] [10];

- Cerebral Palsy [11]; A number of studies proved the association between cerebral palsy and spondylolysthesis, certainly in athetoid cerebral palsy (60%)

- Scheuermanns Disease

- Scoliosis[12]

- Rheumatoid arthritis

- Spinal stenosis[13]

Differential Diagnosis[edit | edit source]

- Spondylolysis [14] [15]

- Metastatic disease [16]

- Low back pain [17]

- Osteoarthritis [17]

- Neuroforaminal stenosis [17]

- Spinal Stenosis [17]

Diagnostic Procedures[edit | edit source]

Physical Examination[edit | edit source]

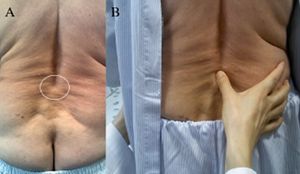

- Step off Sign-A noticeable Step off sign is palpated at the Lumbo sacral area due to slippage of the vertebrae.

- Straight Leg Raise Test-Straight raising of the leg with patient lying on the back causes pain and triggers the entire trunk.

- The clinical signs on examination include: a) flattened lumbar lordosis with palpable step of the spinous process (SP). The prominent SP may be tender in case of traumatic spondylolisthesis due to pars fracture. In isthmic L5/S1 spondylolisthesis the palpable SP is the L5, whereas in dysplastic L5/S1 spondylolisthesis the palpable is the S1; b) limitation of lumbar range of motion in flexion/extension; c) pain with single-limb standing lumbar extension. This manoeuvre is usually painful on the affected side; d) popliteal angles measuring more than 45 indicating hamstring tightness, which is present in 80% of symptomatic patients; e) positive straight leg raise test.[7]

Radiological Examination[edit | edit source]

X Rays - Anteroposterior and lateral plain films, as well as lateral flexion-extension plain films, are the standard for the initial diagnosis of spondylolisthesis. One is looking for the abnormal alignment of one vertebral body to the next as well as possible motion with flexion and extension, which would indicate instability. In isthmic spondylolisthesis, there may be a pars defect, which is termed the "Scotty dog collar." The "Scotty dog collar" shows a hyperdensity where the collar would be on the cartoon dog, which represents the fracture of the pars interarticularis

- The slip angle (SA) was the first to describe the kyphotic relationship of L5 to S1.Together with the percentage of slippage, SA is used to assess segmental instability and progression of spondylolisthesis during conservative or surgical management.

- Lumbo-sacral angle (LSA) relies on landmarks least affected by the spondylolisthesis pathophysiology. It is used to classify spondylolisthesis into: a) non-progressive, with a ‘horizontal’ sacrum producing an LSA of 100 or more, which seldom needs surgery and b) progressive, with a ‘vertical’ sacrum producing an LSA less than 100, which is usually symptomatic requiring surgical treatment. Furthermore, if the LSA fails to improve to 100 or more on preoperative hyperextension and traction films an anterior prior to the posterolateral fusion would be recommended.Even though other angles have been used to assess lumbosacral kyphosis the LSA shows the strongest correlation with the slippage grade.

- Pelvic incidence (PI) is defined as the angle between a perpendicular line to the mid-point of the sacral plate and a line from the mid-point of the sacral plate to the axis of the femoral heads.

- Sacral slope (SS) is the angle of the S1 endplate to the horizontal level.

- Pelvic tilt (PT) is the angle of the line crossing the midpoint of the S1 endplate and the vertical axis of the femoral heads. The PI is the sum of PT and SS (PI ¼ SS þ PI).PI may increase slightly during childhood but remains a constant anatomical parameter following skeletal maturity. In contrast, PT and SS are spatial orientation parameters and may vary for a given pelvis depending on the version or sagittal orientation of the sacrum/pelvis. A high PT indicates a retroverted pelvis, whereas a low PT tends to be associated with an anteverted pelvis. PI corresponds to the size of lumbar lordosis (LL) with deviation of 10 between the two measurements. Increased PI predisposes to the development of isthmic or the progression of dysplastic spondylolisthesis.[7]

Computed tomography (CT) of the spine - provides the highest sensitivity and specificity for diagnosing spondylolisthesis. Spondylolisthesis can be better appreciated on sagittal reconstructions as compared to axial CT imaging.

MRI of the spine can show associated soft tissue and disc abnormalities, but it is relatively more challenging to appreciate bony detail and a potential pars defect on MRI.[1]

Outcome Measures[edit | edit source]

- Disability: Oswestry Disability Index, the SF-36 Physical Functioning scale, the Quebec Back Pain Disability Scale[18]

- Dysfunctional thoughts: Short Form of the Medical Outcomes Study (SF-36)[19]

- Pain: Pain Numerical Rating Scale, VAS.

- Quality of life: Short-Form Health Survey [19]

- Kinesiophobia and Catastrophising: Tampa Scale for Kinesiophobia, Pain Catastrophising Scale[19]

Medical Management[edit | edit source]

For grade I and II spondylolisthesis, treatment typically begins with conservative therapy, including nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), heat, light exercise, traction, bracing, and/or bed rest.

Conservative [edit | edit source]

- Initially resting and avoiding movements like lifting, bending, and sports.[16]

- Analgesics and NSAIDs reduce musculoskeletal pain and have an anti-inflammatory effect on nerve root and joint irritation.

- Epidural steroid injections can be used to relieve low back pain, lower extremity pain related to radiculopathy and neurogenic claudication.[20]

- A brace may be useful to decrease segmental spinal instability and pain. [21]

- Physiotherapy focuses on relieving extension stresses from the lumbosacral junction (hamstring and hip flexor stretching), as well as working on core strengthening (deep abdominal muscles and lumbar multifidus strengthening).

Surgical[edit | edit source]

Approximately 10% to 15% of younger patients with low-grade spondylolisthesis will fail conservative treatment and need surgical treatment.

- No definitive standards exist for surgical treatment.

- Surgical treatment includes a varying combination of decompression, fusion with or without instrumentation, or interbody fusion.

- Patients with instability are more likely to require operative intervention.

- Some surgeons recommend a reduction of the spondylolisthesis if able as this not only decreases foraminal narrowing but also can improve spinopelvic sagittal alignment and decrease the risk for further degenerative spinal changes in the future. The reduction can be more difficult and riskier in higher grades and impacted spondylolisthesis[1]

- The Scott technique utilizing cerclage wire fixation has been successful with satisfactory results varying between 80%–100%. The butterfly plate technique, Pedicle screw hook fixation, Pedicle screw rod fixation in combination with a screw hook, , pedicle screw cable system, and an intralaminar link construct are some of the other surgical techniques.

Physical Therapy Management[edit | edit source]

Spondylolisthesis should be treated first with conservative therapy, which includes physical therapy, rest, medication and braces.[22][23]

The Rehabilitation exercise program should be designed to improve muscle balance rather than muscle strength alone. [24]

Good exercise choices include:

- Isometric and isotonic exercises beneficial for strengthening of the main muscles of the trunk, which stabilize the spine. These techniques may also play a role in pain reduction[25][26][27].

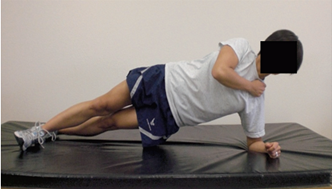

- Core stability exercises, useful in reducing pain and disability in chronic low back pain in patient with spondylolisthesis.[28][24]

- Movements in closed-chain-kinetics, antilordotic movement patterns of the spine, elastic band exercises in the lying position

- Gait training

- Stretching and strengthening exercises, objective of stretching and strengthening is to decrease the extension forces on the lumbar spine, due to agonist muscle tightness, antagonist weakness, or both, which may result in decreased lumbar lordosis.[26] In order to improve the patient’s mobility stretching exercises of the hamstrings, hip flexors and lumbar paraspinal muscles are important.[25][26][27]

- Balance training including - Sensomotoric training on unstable devices, walking in all variations, coordinative skills

Hydrotherapy - Endurance training of muscles, effective for chronic low back pain.[26][29]

- Cardiovascular exercise - Athletes with spondylolysis and first-degree spondylolisthesis can take part in all sports activities. However, attention should be given to those kinds of sport where recurring trauma resulting from repeated flexion, hyperextension and twisting is usually undertaken (e.g. gymnastics, aerobics, swimming in the dolphin technique). Athletes with a grade 2, 3 or 4 can also participate in all the sport activities but have to do this with a special and individually adapted directive.Low aerobic impact sports are highly recommended. Sports that certainly can be practiced are walking, swimming and cross-training. Although these activities will not improve the shift, these sports are a good alternative for cardiovascular exercises. Impact sports like running should not be done in order to avoid wear. The adolescent athlete or manual laborer should avoid hyperextension and/or contact sports.

- Williams flexion exercises are a set of exercises that decrease lumbar extension and focuses on lumbar flexion. These include

- Pelvic Tilts

- Partial sit-ups

- Knee-to-chest

- Hamstring stretch

- Standing lunges

- Seated trunk flexion

- Full squat

Figure 3: Strengthening of the deep abdominal muscles.

Alternating legs, with leg extension while exhaling, maintaining contraction of transverse abdominis, paravertebral and pelvic floor muscles [30]

Figure 4: Horizontal side support exercise for core stability [31] .

Figure 5: Stretching of the erector spine muscles. [30]

Treatment Options Other Than Exercise Include[edit | edit source]

Lumbosacral Braces or Corset[edit | edit source]

In healthy subjects, it has been found that the lumbosacral brace can improve the sitting position of the patient. The fact that there was wear of the brace, indicates that the brace has an important function in the sitting position.[32] According to Prateepavanich et al., a lumbosacral corset can be used to improve walking distance and to reduce pain in daily activities[33], but it does not reduce the shift of the vertebra. It is a good aid during the painful periods but should be discontinued when the patients' complaints are reduced. It aids in decreasing neurogenic claudication while walking.[34]

Education - Posture and Lifting Techniques[edit | edit source]

Special attention has to be given to posture and proper lifting techniques[35] wherein the physiotherapist has an important educational role. Lifting techniques is effective for chronic low back pain.[36][26]

Management of Catastrophising and Kinesiophobia[edit | edit source]

Physical therapy treatment in combination with management of catastrophising and kinesiophobia gave good results. The disability, pain, dysfunctional thoughts were significant reduced.[37]

Massage therapy

A case report showed that the onset of low back pain was delayed during walking/standing. During a prescribed course of massage therapy:[38]

- Hyperlordosis decreased

- Hypertonicity of iliopsoas and quadratus lumborum muscles decreased

- Bilateral net reduction of ilial rotation was achieved, but with irregular changes.

These results were inconclusive but bring into question the role of hip flexor and spinal extensor muscles in normalizing postural misalignment associated with spondylolisthesis[38].

Key Research[edit | edit source]

- Agabegi SS, Fischgrund JS. Contemporary management of isthmic spondylolisthesis: pediatric and adult. The Spine Journal. 2010 Jun 1;10(6):530-43.

- Van Tulder MW, Koes BW, Bouter LM. Conservative treatment of acute and chronic nonspecific low back pain: a systematic review of randomized controlled trials of the most common interventions. Spine. 1997 Sep 15;22(18):2128-56.

- Ferreira PH, Ferreira ML, Maher CG, Herbert RD, Refshauge K. Specific stabilisation exercise for spinal and pelvic pain: a systematic review. Australian Journal of Physiotherapy. 2006 Jan 1;52(2):79-88.

Clinical Bottom Line[edit | edit source]

- An inter-professional team consisting of a speciality-trained orthopedic nurse, physical therapist, and an orthopedic surgeon or neurosurgeon will provide the best outcome and long-term care of patients with degenerative spondylolisthesis.

- Treating clinician will decide on the management plan, and then have the other team members engaged - surgical cases with include the nursing staff in pre-, intra-, and post-operative care, and coordinating with PT for rehabilitation.

- In non-operative cases (majority), the PT keeps the rest of the team informed of progress (or lack of).

- The team should encourage weight loss as weight reduction may reduce symptoms and increase the quality of life.

- Inter-professional collaboration, as above, will drive patient outcomes to their best results.[1]

References[edit | edit source]

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 1.5 1.6 1.7 Tenny S, Gillis CC. Spondylolisthesis. InStatPearls [Internet] 2019 Mar 27. StatPearls Publishing. Available from:https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK430767/ (last accessed 26.1.2020)

- ↑ Iguchi T, Wakami T, Kurihara A, Kasahara K, Yoshiya S, Nishida K. Lumbar multilevel degenerative spondylolisthesis: radiological evaluation and factors related to anterolisthesis and retrolisthesis. Clinical Spine Surgery. 2002 Apr 1;15(2):93-9.

- ↑ Iguchi T, Wakami T, Kurihara A, Kasahara K, Yoshiya S, Nishida K. Lumbar multilevel degenerative spondylolisthesis: radiological evaluation and factors related to anterolisthesis and retrolisthesis. Clinical Spine Surgery. 2002 Apr 1;15(2):93-9.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 Gagnet P, Kern K, Andrews K, Elgafy H, Ebraheim N. Spondylolysis and spondylolisthesis: a review of the literature. Journal of orthopaedics. 2018 Jun 1;15(2):404-7.

- ↑ Foreman P. et al, L5 spondylolysis/spondylolisthesis: a comprehensive review with an anatomic focus, Childs Nerv Syst. 2013;29(2):209-16 (Level of evidence 1B)

- ↑ Wicker A. Spondylolysis and spondylolisthesis in sports: FIMS Position Statement. International SportMed Journal. 2008 Jan 1;9(2):74-8.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 Mataliotakis GI, Tsirikos AI. Spondylolysis and spondylolisthesis in children and adolescents: current concepts and treatment. Orthopaedics and Trauma. 2017 Dec 1;31(6):395-401.

- ↑ Mays S. Spondylolysis, spondylolisthesis, and lumbo‐sacral morphology in a medieval English skeletal population. American Journal of Physical Anthropology: The Official Publication of the American Association of Physical Anthropologists. 2006 Nov;131(3):352-62.

- ↑ Sairyo K, Goel VK, Vadapalli S, Vishnubhotla SL, Biyani A, Ebraheim N, Terai T, Sakai T. Biomechanical comparison of lumbar spine with or without spina bifida occulta. A finite element analysis. Spinal Cord. 2006 Jul;44(7):440-4.

- ↑ Burkus JK. Unilateral spondylolysis associated with spina bifida occulta and nerve root compression. Spine. 1990 Jun 1;15(6):555-9.

- ↑ Sakai T, Yamada H, Nakamura T, Nanamori K, Kawasaki Y, Hanaoka N, Nakamura E, Uchida K, Goel VK, Vishnubhotla L, Sairyo K. Lumbar spinal disorders in patients with athetoid cerebral palsy: a clinical and biomechanical study. Spine. 2006 Feb 1;31(3):E66-70.

- ↑ Sakai T, Sairyo K, Suzue N, Kosaka H, Yasui N. Incidence and etiology of lumbar spondylolysis: review of the literature. Journal of orthopaedic science. 2010 May 1;15(3):281-8.

- ↑ Andersen T, Christensen FB, Langdahl BL, Ernst C, Fruensgaard S, Østergaard J, Andersen JL, Rasmussen S, Niedermann B, Høy K, Helmig P. Degenerative spondylolisthesis is associated with low spinal bone density: a comparative study between spinal stenosis and degenerative spondylolisthesis. BioMed research international. 2013 Jan 1;2013.

- ↑ Tsirikos AI, Garrido EG. Spondylolysis and spondylolisthesis in children and adolescents. The Journal of bone and joint surgery. British volume. 2010 Jun;92(6):751-9.

- ↑ Thein-Nissenbaum J, Boissonnault WG. Differential diagnosis of spondylolysis in a patient with chronic low back pain. Journal of Orthopaedic & Sports Physical Therapy. 2005 May;35(5):319-26.

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 Kalichman L, Kim DH, Li L, Guermazi A, Berkin V, Hunter DJ. Spondylolysis and spondylolisthesis: prevalence and association with low back pain in the adult community-based population. Spine. 2009 Jan 15;34(2):199.

- ↑ 17.0 17.1 17.2 17.3 Metzger R, Chaney S. Spondylolysis and spondylolisthesis: What the primary care provider should know. Journal of the American Association of Nurse Practitioners. 2014 Jan;26(1):5-12.

- ↑ Davidson M, Keating JL. A comparison of five low back disability questionnaires: reliability and responsiveness. Physical therapy. 2002 Jan 1;82(1):8-24.

- ↑ 19.0 19.1 19.2 Monticone M, Ferrante S, Teli M, Rocca B, Foti C, Lovi A, Bruno MB. Management of catastrophising and kinesiophobia improves rehabilitation after fusion for lumbar spondylolisthesis and stenosis. A randomised controlled trial. European spine journal. 2014 Jan;23(1):87-95.

- ↑ Weinstein JN, Lurie JD, Tosteson TD, Hanscom B, Tosteson AN, Blood EA, Birkmeyer NJ, Hilibrand AS, Herkowitz H, Cammisa FP, Albert TJ. Surgical versus nonsurgical treatment for lumbar degenerative spondylolisthesis. New England Journal of Medicine. 2007 May 31;356(22):2257-70.

- ↑ Funao H, Tsuji T, Hosogane N, Watanabe K, Ishii K, Nakamura M, Chiba K, Toyama Y, Matsumoto M. Comparative study of spinopelvic sagittal alignment between patients with and without degenerative spondylolisthesis. European Spine Journal. 2012 Nov;21(11):2181-7.

- ↑ Hu SS, Tribus CB, Diab M, Ghanayem AJ. Spondylolisthesis and spondylolysis. JBJS. 2008 Mar 1;90(3):656-71.

- ↑ Kalpakcioglu B, Altınbilek T, Senel K. Determination of spondylolisthesis in low back pain by clinical evaluation. Journal of Back and Musculoskeletal Rehabilitation. 2009 Jan 1;22(1):27-32.

- ↑ 24.0 24.1 Nava-Bringas TI, Ramírez-Mora I, Coronado-Zarco R, Macías-Hernández SI, Cruz-Medina E, Arellano-Hernández A, Hernández-López M, León-Hernández SR. Association of strength, muscle balance, and atrophy with pain and function in patients with degenerative spondylolisthesis. Journal of back and musculoskeletal rehabilitation. 2014 Jan 1;27(3):371-6.

- ↑ 25.0 25.1 Zimmerman J, Simons SM. Bony healing in a patient with bilateral L5 spondylolysis. Current sports medicine reports. 2005 Jan 1;4(1):35-7.

- ↑ 26.0 26.1 26.2 26.3 26.4 Van Tulder MW, Koes BW, Bouter LM. Conservative treatment of acute and chronic nonspecific low back pain: a systematic review of randomized controlled trials of the most common interventions. Spine. 1997 Sep 15;22(18):2128-56.

- ↑ 27.0 27.1 Sinaki M, Lutness MP, Ilstrup DM, Chu CP, Gramse RR. Lumbar spondylolisthesis: retrospective comparison and three-year follow-up of two conservative treatment programs. Archives of physical medicine and rehabilitation. 1989 Aug 1;70(8):594-8.

- ↑ Ferreira PH, Ferreira ML, Maher CG, Herbert RD, Refshauge K. Specific stabilisation exercise for spinal and pelvic pain: a systematic review. Australian Journal of Physiotherapy. 2006 Jan 1;52(2):79-88.

- ↑ McNeely ML, Torrance G, Magee DJ. A systematic review of physiotherapy for spondylolysis and spondylolisthesis. Manual therapy. 2003 May 1;8(2):80-91.

- ↑ 30.0 30.1 Garcia AN, Costa LD, da Silva TM, Gondo FL, Cyrillo FN, Costa RA, Costa LO. Effectiveness of back school versus McKenzie exercises in patients with chronic nonspecific low back pain: a randomized controlled trial. Physical therapy. 2013 Jun 1;93(6):729-47.

- ↑ Childs JD, Teyhen DS, Casey PR, McCoy-Singh KA, Feldtmann AW, Wright AC, Dugan JL, Wu SS, George SZ. Effects of traditional sit-up training versus core stabilization exercises on short-term musculoskeletal injuries in US Army soldiers: a cluster randomized trial. Physical therapy. 2010 Oct 1;90(10):1404-12.

- ↑ Mathias M, Rougier PR. In healthy subjects, the sitting position can be used to validate the postural effects induced by wearing a lumbar lordosis brace. Annals of physical and rehabilitation medicine. 2010 Oct 1;53(8):511-9.

- ↑ ANICH PP, SANTISATISAKUL P. The Effectiveness of Lumbosacral Corset in Sympto-matic Degenerative Lumbar Spinal Stenosis. J Med Assoc Thai. 2001;84:572-6.

- ↑ Bydon M, Alvi MA, Goyal A. Degenerative lumbar spondylolisthesis. definition, natural history, conservative management, and surgical treatment. 2019 Jul 5;30:299-304.

- ↑ Agabegi SS, Fischgrund JS. Contemporary management of isthmic spondylolisthesis: pediatric and adult. The Spine Journal. 2010 Jun 1;10(6):530-43.

- ↑ McNeely ML, Torrance G, Magee DJ. A systematic review of physiotherapy for spondylolysis and spondylolisthesis. Manual therapy. 2003 May 1;8(2):80-91.

- ↑ Monticone M, Ferrante S, Teli M, Rocca B, Foti C, Lovi A, Bruno MB. Management of catastrophising and kinesiophobia improves rehabilitation after fusion for lumbar spondylolisthesis and stenosis. A randomised controlled trial. European spine journal. 2014 Jan;23(1):87-95.

- ↑ 38.0 38.1 Halpin S. Case report: The effects of massage therapy on lumbar spondylolisthesis. Journal of bodywork and movement therapies. 2012 Jan 1;16(1):115-23.

![Scottie dog .png[5]](/images/a/a4/Scottie_dog.png)