Lumbar Radiculopathy

Original Editors -Clay McCollum

Top Contributors - Admin, Liena Lamonte, Clay McCollum, Bo Hellinckx, Kim Jackson, Lucinda hampton, David De Meyer, Liesbeth De Feyter, Eric Robertson, Khloud Shreif, Rachael Lowe, Bram Van Laer, Lynse Brichau, Simisola Ajeyalemi, WikiSysop, Kai A. Sigel, 127.0.0.1, Adam James, Rewan Elsayed Elkanafany, Mariam Hashem, Barb Clemes, Vidya Acharya, Candace Goh and Jess Bell

Definition/Description[edit | edit source]

Lumbosacral radiculopathy is a disorder that causes pain in the lower back and hip which radiates down the back of the thigh into the leg. This damage is caused by compression of the nerve roots which exit the spine, levels L1- S4. The compression can result in tingling, radiating pain, numbness, paraesthesia, and occasional shooting pain. Radiculopathy can occur in any part of the spine, but it is most common in the lower back (lumbar-sacral radiculopathy) and in the neck (cervical radiculopathy). It is less commonly found in the middle portion of the spine (thoracic radiculopathy).[1]

Overall, lumbosacral radiculopathy is an extraordinarily common complaint seen in clinical practice and comprises a large proportion of annual doctor visits. The vast majority of cases are benign and will resolve spontaneously, and thus, conservative management is the most appropriate first step in the absence of clinical red flag symptoms. In cases where symptoms fail to resolve, imaging studies, electromyography, and nerve conduction studies can assist in making a diagnosis.[2]

Radiculopathy is not the same as “radicular pain” or “nerve root pain”. Radiculopathy and radicular pain commonly occur together, but radiculopathy can occur in the absence of pain and radicular pain can occur in the absence of radiculopathy.[3]

- Radiculopathy can be defined as the whole complex of symptoms that can arise from nerve root pathology, including anesthesia, paresthesia, hypoesthesia, motor loss and pain.

- Radicular pain and nerve root pain can be defined as a single symptom (pain) that can arise from one or more spinal nerve roots.[4] Lumbar sacral radiculopathy is a disorder of the spinal nerve roots from L1 to S4.

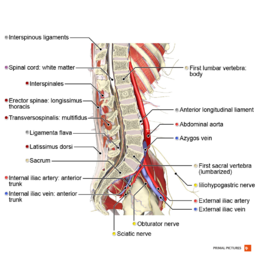

Clinically Relevant Anatomy[edit | edit source]

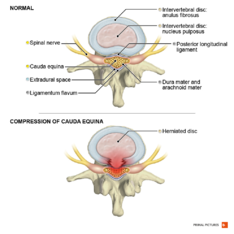

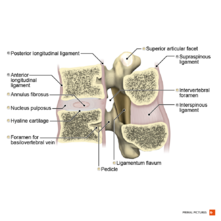

The lumbar nerve roots exit beneath the corresponding vertebral pedicle through the respective foramen.

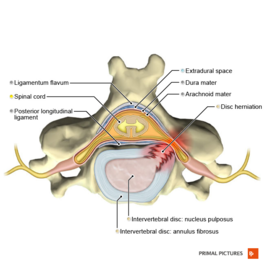

Since most disc herniations occur posterolaterally, the root that gets compressed is actually the root that exits the foramen below the herniated disc. So, a disc protrusion at L4/L5 will compress the L5 root, and a protrusion at L5/S1 will compress the S1 root.

Ninety-five percent of disc herniations occur at the L4/5 or L5/S1 disc spaces. Herniations at higher levels are uncommon.[5]

Epidemiology[edit | edit source]

While the literature lacks concise epidemiologic data, most reports estimate about a 3% to 5% prevalence rate of lumbosacral radiculopathy in patient populations. Moreover, the condition constitutes a significant reason for patient referral to either neurologists, neurosurgeons, or orthopedic spine surgeons. [2]

Lower back pain is severely common in the general population, but lumbar radiculopathy has only been reported with an incidence of 3 to 5%. [4]

5-10% of patients with low back pain have sciatica. the annual prevalence of disc-related sciatica in the general population is estimated at 2,2%. [6]

Prognosis is in most cases favorable, the pain and related disabilities resolving within two weeks.[6]. But at the same time, a substantial group (30%) continues to have pain for one year or longer.[6]

Lumbar radiculopathy is a disorder that commonly arises with significant socio-economical consequences. The discal origin of a lumbar radiculopathy incidence is around 2%. Out of a 12.9% incidence of low back complaints within working population, 11% is due to lumbar radiculopathy.[7]

The prevalence of lumbosacral radiculopathy has been situated from 9.9% to 25%.[8]

Risk factors for radiculopathy are activities that place an excessive or repetitive load on the spine. Patients involved in heavy labour or contact sports are more prone to develop radiculopathy than those with a more sedentary lifestyle.

Pathophysiology[edit | edit source]

Lumbosacral radiculopathy is the clinical term used to describe a predictable constellation of symptoms occurring secondary to mechanical and/or inflammatory cycles compromising at least one of the lumbosacral nerve roots. The noxious stimulus on a spinal nerve creates ectopic nerve signals that are perceived as pain, numbness, and tingling along the nerve distribution. [2]

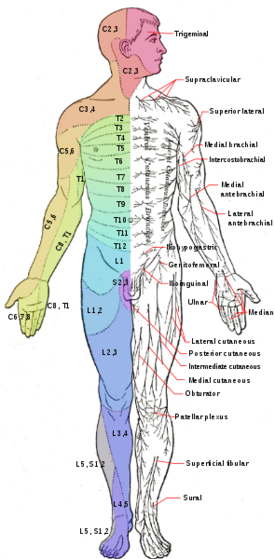

Patients can present with radiating pain, numbness/tingling, weakness, and gait abnormalities across a spectrum of severity. Depending on the nerve root(s) affected, patients can present with these symptoms in predictable patterns affecting the corresponding dermatome or myotome[2].

Clinical Presentation[edit | edit source]

Causes include

- Lesions of the intervertebral discs and degenerative disease of the spine, most common causes of lumbosacral radiculopathy.[2]

- Herniated disc with nerve root compression causes 90% of radiculopathy [6]

- Tumors (less often)[6]

- Lumbar Spinal Stenosis caused by congenital abnormalities or degenerative changes. Lumbar stenosis can be described as the narrowing of the spinal canal and compressing the nerve caused by the underlying causes as mentioned above.[4]

- Scoliosis can cause the nerves on one side of the spine to become compressed by the abnormal curve of the spine.

- underlying diseases like infections such as osteomyelitis. [6]

In patients under 50 years, a herniated disc is the most frequent cause. After the age of 50, radicular pain is often caused by degenerative changes in the spine (stenosis of the foramen intravertebral). [4] Risk factors for acute lumbar radiculopathy are:[6]

- Age (peak 45-64 years)

- Smoking

- Mental stress

- Strenuous physical activity (frequent lifting)

- Driving (vibration of the whole body)

Indication for sciatica/symptoms: [6]

- Unilateral leg pain greater than low back pain, leg pain follows a dermatomal pattern[6] [9]

- Pain traveling below the knee to foot or toes

- Numbness and paraesthesia in the same area

- Straight leg raise positive, induces more pain

Clinical presentation depends on the cause of the radiculopathy and which nerve roots are being affected. Also important is the nature (sharp, dull, piercing, throbbing, stabbing, shooting, burning) and localisation of the pain[10]. Some patients report, besides radicular leg pain, also neurological signs such as paresis, sensory loss. or loss of reflexes. If not present, this is not radiculopathy.

Clinical presentation for radiculopathy from each lumbar nerve root:

| Nerve Root | Dermatomal area | Myotomal area | Reflexive changes |

| L1 | Inguinal region | Hip flexors | |

| L2 | Anterior mid-thigh | Hip flexors | |

| L3 | Distal anterior thigh | Hip flexors and knee extensors | Diminished or absent patellar reflex |

| L4 | Medial lower leg/foot | Knee extensors and ankle dorsiflexors | Diminished or absent patellar reflex |

| L5 | Lateral leg/foot | Hallux extension and ankle plantar flexors | Diminished or absent achilles reflex |

| S1 | Lateral side of foot | Ankle plantar flexors and evertors | Diminished or absent achilles reflex |

Differential Diagnosis[edit | edit source]

Radicular syndrome/ Sciatica: a disorder with radiating pain in one or more lumbar or sacral dermatomes, and can be accompanied by phenomena associated with nerve root tension or neurological deficits.[3]

- Pseudoradicular syndrome

- Thoracic disc injuries

- Low back pain

- Cauda equina

- Inflammatory/metabolic causes[7]: Diabetes, Ankylosing spondylitis, Paget’s disease, Arachnoiditis, Sarcoidosis

- trochanteric bursitis

- Intraspinal synovial cysts

Diagnostic Procedures [edit | edit source]

Clinical evaluation:

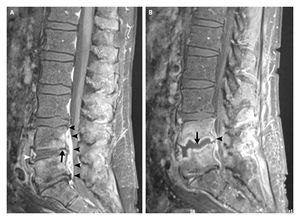

- X-rays: to identify the presence of trauma or osteoarthritis and early signs of a tumor or an infection

- EMG: useful in detecting radiculopathies but they have limited utility in the diagnosis. In patients with clinical suspicion of lumbosacral radiculopathy and normal MRI findings, EMG may help in diagnosing nerve root involvement in patients with otherwise unexplained leg pain.[6]

- MRI: used to see if disc herniation and nerve root compression are present in patients with clinical suspicion of lumbosacral radiculopathy.[8]

Outcome Measures[edit | edit source]

- Roland Morris Disability Questionnaire (RMDQ) - The Roland Morris Disability Questionnaire assess changes in functional status after treatment in patients with low back pain. The Questionnaire is widely used for health status.[3][4]

- Back Pain Functional Scale - A scale for self-report measure that evaluates functional ability in people with back pain.[9]

- The Maine-Seattle Back Questionnaire - A 12-item disability questionnaire for evaluating patients with lumbar sciatica or stenosis.[10]

- Fear Avoidance Belief Questionnaire (FABQ) - this questionnaire is developed by Waddell to investigate fear-avoidance beliefs among LBP patients in the clinical setting.[11]

- Oswestry Low Back Pain Disability Questionnaire - considered as ‘the golden standard’ to measure the permanent functional disability of the lower back. [3]

- The Quebec back pain disability scale (QBPDS) - used to measure the functional disability for patients with lower back pain. [4]

Examination[edit | edit source]

Diagnosed by history taking and physical examination.[6] Motor, sensory, and reflex functions should be assessed to determine the affected nerve root level.[6]

If the patient reports the typical unilateral radiating pain in the leg and there is one or more positive neurological test result the diagnosis of sciatica seems justified.[6]

Clinical evaluation of lumbosacral radiculopathy begins with:

Medical history (type, location, and duration of symptoms, presence of subjective weakness and dysesthesia, current therapy, dermatomal radiation, absence of work) and physical examination: dermatomal sensory loss, myotomal weakness, straight leg raise[12][6], Crossed Straight Leg Raise Test, Femoral Nerve Stretch Test and reflexes.

If the patients report the typical unilateral radiating pain in the leg and there is one or more positive neurological test result, the diagnosis of sciatica seems justified. [6]

Straight Leg Raise test (Lasègue test):

The best known clinical test is the straight-leg raising test[7] The supine SLR is more sensitive than the seated SLR when it comes to the diagnosis of lumbar disc herniation with radiculopathy. A pooled sensitivity for straight leg raising test was 0. 91 (95% CI 0.82-0.94), a pooled specificity 0.26 (95% CI 0.16-0.38)[7]. The test is based on stretching of the nerves in the spine[8]

Crossed Straight Leg Raise Test (Crossed Lasègue test):

A test for the containment and exclusion of lumbar radiculopathy. For the cross straight leg raising test a pooled sensitivity was 0.29 (95% CI 0.24-0.34), pooled specificity was 0.88 (95% CI 0.86-0.90)[7](LOE 1A). The test is based on stretching of the nerves in the spine.[8]

Femoral Nerve Stretch Test:

For the Femoral Nerve Stretch Test, the patient lies prone with the knee passively flexed to the thigh. The test is positive if the patient experiences anterior thigh pain. This test causes a downward and slightly lateral movement of the femoral nerve, its nerve root, and the intradural rootlet.[6]

Specific vertebral level

To diagnose L4 radiculopathy the clinician placed emphasis on the femoral nerve stretch test, the straight leg raise test, the knee reflex, sensory loss in the L4 dermatome, and the muscle power for the ankle dorsiflexion.

To diagnose L5 radiculopathy, the clinician focused on the straight leg raise test, sensory loss in the L5 dermatome, and the muscle power for the hip abduction, ankle dorsiflexion, ankle eversion, and the big toe extension.

For S1 radiculopathy the clinician emphasised the straight leg raise test, the ankle reflex, sensory loss in the S1 dermatome, and the muscle power for hip extension, knee flexion, ankle plantarflexion, and ankle eversion.[6]

Medical Management[edit | edit source]

Treatment is varied depending on the etiology and severity of symptoms.

Conservative management of symptoms is generally considered the first line.

- Medications are used to manage pain symptoms including NSAIDs, acetaminophen, and in severe cases, opiates. Radicular symptoms are often treated with neuroleptic agents. Systemic steroids are often prescribed for acute low back pain, although there is limited evidence to support its use. Nonpharmacologic interventions are often utilised as well.

- Physical therapy, acupuncture, chiropractic manipulation, and traction are all commonly used in the treatment of lumbosacral radiculopathy. Of note, the data supporting the use of these treatment modalities is equivocal.

- Interventional techniques are also commonly used and include epidural steroid injections and percutaneous disc decompression. In refractory cases, surgical decompression and spinal fusion can be performed.

The international consensus says that in the first 6-8 weeks, conservative treatment is indicated.[4]. Surgery should be offered only if complaints remain present for at least 6 weeks after a conservative treatment.[9] . By research the majority of radiculopathy patients respond well to this conservative treatment, and symptoms often improve within six weeks to three months.

Study results

- A 2016 study revealed that appropriate use of EI (= epidural injections) to treat sciatica could significantly improve the pain score and functional disability score leading to a decrease in surgical rate.. [15]

- A study evaluating the effect of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, or Cox-2 inhibitors reported that the drugs have a significant effect on acute radicular pain compared with placebo.[10] But other studies say that there are no positive effects on lumbar radicular pain.[12]

- Studies on the effect of acupuncture in people with acute lumbar radicular pain found a positive effect on the pain intensity and pain threshold.[11]

- Among patients with acute lumbar radiculopathy, oral steroids (prednisone) will relieve them from pain and improve function.[7]

- Another study concluded: short term there is no evidence in favor of traction when compared to sham (fake) traction or other conservative treatments[12]; short term there is no evidence in favour of physical therapy compared to inactive treatment (bed rest), other conservative treatments or surgery.[6]; At the short term, there is no evidence in favour of manipulation compared to other conservative treatments or chemonucleolysis.[3] A recent systematic review concludes that vertical traction (VT) does not give additional benefits when combined with or compared with PT treatments due to insufficient data in patients with Lumbar Radiculopathy. Further research and new high-quality studies are needed to investigate VT's effectiveness, most effective delivery, treatment dosage, or the pain stage that could benefit more from this intervention. The review suggests that VT may be an effective treatment only for reducing pain for short-term and may be preferred to passive treatments as bed rest and medications; however, there was no positive effect on increasing physical activity.[16]

Surgical[edit | edit source]

Surgical intervention for sciatica is called a discectomy and focuses on the removal of disc herniation and eventually a part of the disc. [6] Spinal fusion is another option. Next to simple discectomy and spinal fusion, there are 3 other surgical treatments which can be applied in patients with disc herniation: 1) chemonucleolysis 2) percutaneous discectomy 3) microdiscectomy. [10]

- 90% of all patients who have had surgery for lumbar disc herniation underwent discectomy alone, although the number of spinal fusion procedures has greatly increased.

- The complication rate of simple discectomy is reported at less than 1%.

Physical Therapy Management[edit | edit source]

The main problem is that the nerve is pinched in the intervertebral foramen.

- In an acute phase, there is moderate evidence for spinal manipulation for symptomatic relief[15][12].

- For chronic lumbar radiculopathy, only low-level evidence was found for manipulations [7] Because the pain is due to a narrowing of the intervertebral foramen normal traction of the lower spine will also relieve the pain [10]

Besides relieving the pain the patient also needs muscle training, more specific stabilisation.

- The Pilates exercises are not only working for stabilisation but also for the awareness of the body.[6] An exercise that is known to relieve the pain in the lower back is the McKenzie exercise. [8] The main goal of the therapy is reducing the pain. The first thing the patient needs to learn is the awareness of his body (back school) [10] reduces the pain.

- Physical therapy can include mild stretching and pain relief modalities, conditioning exercise, and ergonomic program. A comprehensive rehabilitation program includes postural training, muscle reactivation, correction of flexibility and strength deficits, and subsequent progression to functional exercises.[17]

Exercise therapy is often the first line treatment. However, until now, evidential value for this is lacking.[9][10].

- In randomised study, they wanted to demonstrate what the effect was after a 52 week- rehabilitation program; first exercise therapy in combination with conservative therapy and on the other hand only the conservative treatment. (79% versus 56% Global Perceived Effect, respectively). A systematic review concluded that traction and exercise therapy are is effective.[12]

- Moderate evidence favors stabilization exercises over no treatment, manipulation over sham manipulation, and the addition of mechanical traction to medication and electrotherapy. There was no difference among traction, laser, and ultrasound.[8]

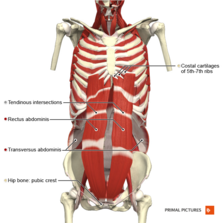

When a patient complains about instability, core stability is really important. Core stabilisation exercise (CSE) with the abdominal drawing-in manoeuvre (ADIM) technique is commonly used. These exercises activate the deep abdominal muscles with minimal activity of the superficial muscles.[12]

Core Stabilisation Exercises[edit | edit source]

Isolated transversus abdominis and lumbar multifidus training

1. Train transversus abdominis muscle activation in a prone lying position without spinal and pelvic movements for 10 seconds with ten repetitions. Keep respiration normal. You gently draw in the lower anterior abdominal wall below the navel level (abdominal drawing-in maneuver) with supplemented contraction of pelvic floor muscles, control your breathing normally, and have no movement of the spine and pelvis while lying prone on a couch with a small pillow placed beneath your ankles. Train lumbar multifidus muscle activation in an upright sitting position. You raise the contralateral arm while performing the abdominal drawing-in maneuver in a sitting position on a chair.

Integrated transversus abdominis and lumbar multifidus training light activities

2. Perform co-contraction of transversus abdominis and lumbar multifidus muscles while sitting on a chair. You use the index and middle fingers to palpate the contraction of the transversus abdominis muscle and the opposite two fingers to palpate the contraction of lumbar multifidus muscle. This exercise progresses from 10- to 60-second holds of co-contraction for ten repetitions.

Train co-contraction of these muscles with trunk forward and backward while sitting on a chair and keeping your lumbar spine and pelvis in a neutral position. The second exercise this week required 10-second holds with ten repetitions.

3. Perform co-contraction of the two muscles in a crooked lying position with both hips at 45 degrees and both knees at 90 degrees. Then you abduct one leg to 45 degrees of hip abduction and hold it for 10 seconds.

Train co-contraction of these muscles in a crooked lying position with both hips at 45 degrees and both knees at 90 degrees. Then you slide a single leg down until the knee is straight, maintain it for 10-second holds and then slide it back up to the starting position.

4. Perform co-contraction of the two muscles while sitting on a balance board. You perform co-contraction of the muscles with trunk forward, backward, and sideways while sitting on a balance board and keeping your lumbar spine and pelvis in a neutral position. You perform each pose for 10-second holds with ten repetitions.

Integrated transversus abdominis and lumbar multifidus training heavier activities

5. Perform co-contraction of the two muscles while raising the buttocks off a couch from a crooked lying position until your shoulders, hips, and knees are straight. You sustain this position for 10 seconds and then lower the buttocks back down to the couch with ten repetitions.

Train muscle co-contraction while raising the buttocks off a couch from a crooked lying position with one leg crossed over the supporting leg. You raise the buttocks off the couch until the shoulders, hips, and knees are straight. You sustain this position for 10 seconds and then lower the buttocks back down to the couch with ten repetitions.

6. Perform co-contraction of the two muscles while raising a single leg from a four-point kneeling position and keeping your back in a neutral position. You sustain this pose for 10 seconds and then return the leg to the starting position with ten repetitions.

Train muscle co-contraction while raising an arm and alternate leg from a four-point kneeling position and keeping your back in a neutral position. You sustain this pose for 10 seconds and then return to the starting position with ten repetitions.

7. Perform co-contraction of the two muscles in a standing position while a mini ball is behind your upper back and against the wall. You flex the hip and knee of one leg to 90 degrees. Sustain this pose for 10 seconds and then return to the starting position with ten repetitions.

Train the muscle co-contraction in a standing position with ankle movement. Perform ankle movement in the forward-backward direction while keeping your lumbar spine in a neutral position. Sustain this pose for 10 seconds and then return to the starting position with ten repetitions.

Integrated transversus abdominis and lumbar multifidus training in pain aggravating activities

8–10. Perform muscle co-contraction while walking at normal, faster and fastest speed for 5 minutes at weeks 8, 9, and 10 respectively. In addition, choose two aggravating activities or tasks that you anticipate would cause pain or instability and perform muscle co-contraction while doing these activities or tasks without having pain. Each aggravating activity or task is performed for 2.5 minutes.

References[edit | edit source]

- ↑ Iversen T, Solberg TK, Romner B, Wilsgaard T, Nygaard Ø, Brox JI, Ingebrigtsen T. Accuracy of physical examination for chronic lumbar radiculopathy. BMC musculoskeletal disorders. 2013 Dec 1;14(1):206.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 2.4 Alexander CE, Varacallo M. Lumbosacral Radiculopathy. InStatPearls [Internet] 2019 Mar 23. StatPearls Publishing. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK430837/ (last accessed 23.1.2020)

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 3.4 Bogduk N. On the definitions and physiology of back pain, referred pain, and radicular pain. Pain. 2009 Dec 1;147(1):17-9.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 4.4 4.5 4.6 Murphy DR, Hurwitz EL, Gerrard JK, Clary R. Pain patterns and descriptions in patients with radicular pain: Does the pain necessarily follow a specific dermatome?. Chiropractic & Osteopathy. 2009 Dec 1;17(1):9.

- ↑ Randall Wright MD, Steven B. Inbody MD, in Neurology Secrets (Fifth Edition), 2010 Radiculopathy and Degenerative Spine Disease Available from: ☀https://www.sciencedirect.com/topics/neuroscience/lumbar-nerves (last accessed 23.1.2020)

- ↑ 6.00 6.01 6.02 6.03 6.04 6.05 6.06 6.07 6.08 6.09 6.10 6.11 6.12 6.13 6.14 6.15 6.16 6.17 6.18 6.19 Coster S, De Bruijn SF, Tavy DL. Diagnostic value of history, physical examination and needle electromyography in diagnosing lumbosacral radiculopathy. Journal of neurology. 2010 Mar 1;257(3):332-7.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 7.3 7.4 7.5 7.6 Tarulli AW, Raynor EM. Lumbosacral radiculopathy. Neurologic clinics. 2007 May 1;25(2):387-405.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 8.2 8.3 8.4 8.5 Kennedy DJ, Noh MY. The role of core stabilization in lumbosacral radiculopathy. Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation Clinics. 2011 Feb 1;22(1):91-103.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 9.2 9.3 Keith L. Moore et al.; Clinically oriented anatomy seventh edition; Wolters Kluwer; p 556-632; 2014

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 10.2 10.3 10.4 10.5 10.6 Valentyn Serdyuk; Scoliosis and spinal pain sydrome: new understanding of their origin and ways of successful treatment;Byword books; p47; 2014

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 Winnie AP, Ramamurthy S, Durrani Z. The inguinal paravascular technic of lumbar plexus anesthesia: the “3-in-1 block”. Anesthesia & Analgesia. 1973 Nov 1;52(6):989-96.

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 12.2 12.3 12.4 12.5 Vloka JD, Hadžic A, April E, Thys DM. The division of the sciatic nerve in the popliteal fossa: anatomical implications for popliteal nerve blockade. Anesthesia & Analgesia. 2001 Jan 1;92(1):215-7.

- ↑ Clinical Examination Videos. TStraight leg raise test - Lasegue’s sign. Available from: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=JmvGHszR_X4[last accessed 26/1/2020]

- ↑ John Gibbons. How to test the Femoral Nerve (Lumbar Plexus L2,3,4) or reverse Lasegue's. Available from: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=cN0uou-nZH8[last accessed 26/1/2020]

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 Farny J, Drolet P, Girard M. Anatomy of the posterior approach to the lumbar plexus block. Canadian journal of anaesthesia. 1994 Jun 1;41(6):480-5.

- ↑ Vanti C, Turone L, Panizzolo A, Guccione AA, Bertozzi L, Pillastrini P. Vertical traction for lumbar radiculopathy: a systematic review. Archives of physiotherapy. 2021 Dec;11(1):1-1.

- ↑ Kennedy DJ et al. The role of core stabilization in lumbosacral radiculopathy. Phys Med Rehabil Clin N Am. 2011 Feb