Congenital Spine Deformities

Top Contributors - Ine Van de Weghe, Gertjan Peeters, Lucinda hampton, Scott Cornish, Kim Jackson, Admin, WikiSysop, Mande Jooste, Chelsea Mclene, De Maeght Kim and Mila Andreew

Introduction[edit | edit source]

Congenital spine deformities are disorders of the spine that develop in an individual prior to birth. The vertebrae do not form correctly in early fetal development and in turn cause structural problems within the spine and spinal cord. These deformities can range from mild to severe and may cause other problems if left untreated, such as developmental problems with the heart, kidneys and urinary tract, problems with breathing or walking, and paraplegia (paralysis of the lower body and legs).

Medical researchers are still unsure of what actually causes the defects responsible for congenital spine deformities. In these disorders, the vertebrae are often missing, fused together and/or misshapen or partially formed.[1]

Etiology[edit | edit source]

The causes of congenital vertebral anomalies are likely to be

- Genetic factors, e.g. defects in the Notch signalling pathways. (Notch 1 gene has been shown to coordinate the process of somitogenesis by regulating the development of vertebral precursors in mice), Chromosome 13 and 17 translocations (associated with the development of hemivertebrae). Genetic theories are supported by molecular, animal, and twin population studies.

- Environmental factors have also been suggested, and these include exposure to toxins including carbon monoxide, the use of antiepileptic medication, and maternal diabetes.[2]

Types[edit | edit source]

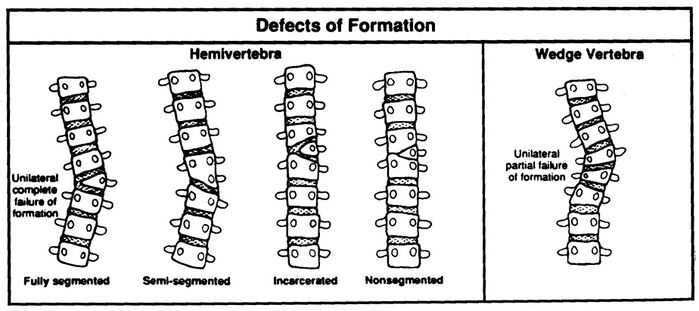

The spectrum of congenital deformities of the spine includes a range of conditions that blend gradually from scoliosis through kyphoscoliosis to pure kyphosis. These deformities occur when an asymmetric failure of development of one or more vertebrae results in a localized imbalance in the longitudinal growth of the spine and an increasing curvature affecting the coronal and/or sagittal plane, with a risk for progression during skeletal growth.

The consequence of unbalanced growth of the spine can be the:

- Development of a benign curve with slow or no progression, in which case observation may be the only treatment required.

- Types of vertebral abnormalities that produce considerable asymmetry in spinal growth and the development of very aggressive deformities with consequent functional, cosmetic, respiratory, and neurological complications. Understanding the anatomical features of the individual vertebral anomalies and their relation to the remainder of the spine makes it possible to predict those abnormalities that are likely to produce a severe curve. Recognizing the natural history of the deformity at an early stage can in turn allow appropriate surgical treatment, with the aim of preventing the development of severe spinal curvature and trunk decompensation.[2]

Examples of a congenital spinal deformities include:

- Congenital Thoracic Hyperkyphosis

- Congenital Scoliosis

Characteristics/Clinical Presentation[edit | edit source]

Congenital abnormalities of the spine have a range of clinical presentations. Some congenital abnormalities may be benign, causing no spinal deformity and may remain undetected throughout a lifetime.

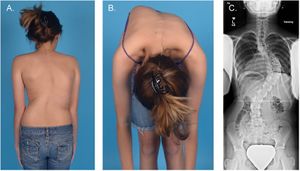

Some deformities will result in sagittal plane abnormalities, for e.g. kyphosis or lordosis, whereas others will primarily affect the coronal plane e.g. scoliosis. The resultant spinal deformity is often a complex, three-dimensional structure with differences in both the coronal and sagittal plane, along with a rotational component along the axis of the spine.[4]

Symptoms of Congenital Spine Deformities[edit | edit source]

Doctors often detect any spine deformity at birth if there is any abnormal curvature in the back. However, some spine deformities until later in childhood and/or adolescence when symptoms worsen. Physical signs of congenital spine deformities typically include:

- Tilted pelvis

- Difficulty walking

- Difficulty breathing

- Abnormal curvature or twisting in the back, left or right, forward or backward

- Uneven shoulders, hips, waist or legs

Respiratory Implications[edit | edit source]

Abnormal development of the spine can cause significant scoliosis, kyphosis, or lordosis, resulting in body deformities that can be distressing to patients and their families. The more serious threat to long-term health is the adverse effect of abnormal development of the spine on pulmonary function.

- This is well documented for curves exceeding 90 degrees, which cause severe restrictive lung disease, but not well understood for lesser curves. Pulmonary function is an important determinant of long-term survival.

- Increased rates of mortality, mostly resulting from pulmonary failure, have been seen in patients with untreated infantile scoliosis beginning at the age of 20 years, with a rise in mortality rates to fourfold above normal by the age of 60 years[5]

Diagnostic Procedures[edit | edit source]

There are several different procedures that can be used to carry out the imaging of the spine. [6]

- X-Rays are useful for showing structural deformities such as hemivertebrae, butterfly vertebra, or incomplete fusion of posterior elements. X-ray is used if no imaging of the spinal cord is required. For scoliosis, erect posterior-anterior frontal and/or lateral views (with breast shielding) are usually obtained. [7]

- MRI is most frequently used for imaging of the spine in adults as the spinal canal and its content can be analysed.

- CT Scans continue to be the preferred method for the assessment of localised bony abnormalities, or a calcified component, of the spinal canal, foramina, neural arches, and articular structures. [7]

Treatment[edit | edit source]

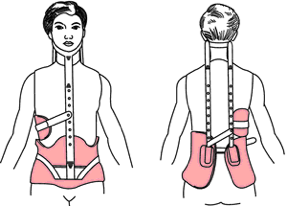

In most cases, nonoperative treatment options are recommended before surgery is considered. Nonoperative treatment options typically include pain medication, certain braces and physical therapy (that includes gait and posture training).

Surgery[edit | edit source]

Surgery Is Considered If:

- The spinal deformity is progressing

- The condition has caused unbearable physical deformity

- The patient experiences chronic pain that cannot be relieved by nonoperative treatment options

- The condition has caused compression of the nerve roots or spinal cord[1]

Spinal instrumentation for congenital spine deformity cases is safe and effective, [8] [9] as is growing rod surgery for selected patients with congenital spinal deformities. [10] [11] The size and weight of the patient determines the size of the spinal implants, whereas the surgical fixation anchors are determined by the anatomy of the patient and the anomalies present. [9] The complications associated with the use of this spinal instrumentation are infrequent and the curve correction, length of immobilisation and fusion rate is improved.[9]

- Growing Rod Surgery: Growing rod surgery is one of the options for the correction of scoliosis, a modern alternative treatment for young children with early onset scoliosis. The incidence of complication remained relatively low [10] [11] and is also recommended for patients where the primary problem is at the vertebral column.

- Expansion Thoracostomy and VEPT: For severe congenital spine deformations, when a large amount of growth remains, expansion thoracostomy and VEPTR (a curved metal rod designed for many uses), are the most appropriate choice. Used when the primary problems involve the thoracic cage, eg when there are rib fusions and/or with developing Thoracic Insufficient Syndrome, [11] but the incidence of complications using VEPTR is, however, relatively high.[12]

- Resection and Fusion: For treating congenital scoliosis caused by hemivertebra posterior hemivertebra, resection and monosegmental fusion appears to be effective. This treatment results in an excellent correction in both the frontal and sagittal planes. [13] Early surgery is typically prescribed as a treatment for children with congenital scoliosis, even though there is little evidence for its long term results. [12]

Physical Therapy[edit | edit source]

The ICF has underscored the need for therapists to provide a holistic approach to treatment, focusing not only on exercises, stretches, and what a child is unable to do, but also on the child’s abilities. The approach to therapy is functional and questions whether a child can actively participate with his or her current level of function.

A physiotherapy assessment is required for children with early onset scoliosis to enable them to function to their fullest potential within society. Assessments provide a baseline for future interventions and establish goals that are appropriate and achievable for the child and the family within their environment.

- Many factors are involved the assessment including the pathology of the child’s condition, family input and expectations, the child’s environment, the equipment needs, and the ability to access services.

- This assessment is necessary to establish what is required for each individual.

An initial assessment may consist of observation of the child at play. This is most appropriately undertaken within the home environment, where the child will be most at ease and will play with his or her own toys. However, this may not always be possible. Play provides many benefits for both child and therapist.

Play is the most likely way in which rapport will be established between the child and the therapist, but it also provides the opportunity to observe a variety of factors when eg In what position does the child play when lying, sitting and/or standing; Does the child move from one position to another?; How does the child move?; What motivates the child in his or her play?; What kind of toys does the child choose?

It is important within the role of physiotherapist to consider the following:

- The child’s abilities, needs, hobbies;

- Needs of the family members and what is important to them;

- Role of the child within the family, especially if the child has siblings;

- The environments inside and outside the home to which the child has access and the child’s level of activity and participation.[14]

See physiotherapy sections in these great pages

Outcome Measures[edit | edit source]

The most commonly used questionnaires with patients who have undergone spinal surgery include

- Owestry Disability Index [15] [16] [17]

- Brief Pain Inventory [16]

- Roland–Morris disability questionnaire [16] [17]

References[edit | edit source]

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Khavkinckinic Congenital spinal deformities Available:https://khavkinclinic.com/congential-spine-deformities/ (accessed 10.10.2021)

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Musculoskeletalkey 6 Congenital Deformities of the Spine Available: https://musculoskeletalkey.com/6-congenital-deformities-of-the-spine/ (accessed 10.10.2021)

- ↑ Klemme WR et al. (2001). Hemivertebral excision for congenital scoliosis in very young children. J Pediatr Orthop. 21 (6), pp761-764.

- ↑ Kawakami N, et al. (2009). Classification of congenital scoliosis and kyphosis: a new approach to the three-dimensional classification for progressive vertebral anomalies requiring operative treatment, Spine (Phila Pa 1976), 34 (17), pp1756-65

- ↑ Musculokeletalkey Respiratory Implications of Abnormal Development of the Spine Available:https://musculoskeletalkey.com/4-respiratory-implications-of-abnormal-development-of-the-spine/ (accessed 10.10.2021)

- ↑ SORANTIN E. et al., 2008 “MRI of the Neonatal and Paediatric Spine and Spinal Canal“, European Journal of Radiology, vol. 68, nr. 2, p. 227 – 234

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 Patrick D Barnes. (2009). Pediatric radiology : chapter 9, spine imaging. (3). Mosby

- ↑ Hedequist D.J. (2009). Instrumentation and fusion for congenital spine deformities, Spine (Phila Pa 1976), 1;34 (17), pp1783-90

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 9.2 Hedequist D.J. et al. (2004). The safety and efficacy of spinal instrumentation in children with congenital spine deformities, Spine (Phila Pa 1976), 15;29 (18), pp 2081-2086

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 Elsebai HB et al.,2011 “Safety and Effficacy of Growing Rod Technique for Pediatric Congenital Spinal Deformities“, J Pediatr Orthop, vol 31, nr 1, pp 1-5. Jan-Feb,

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 11.2 Yazici M. and Emans J.2009, “Fusionless Instrumentation Systems for Congenital Scoliosis: Expandable Spinal Rods and Vertical Expandable Prosthetic Titanium Rib in the Management of Congenital Spine Deformities in the Growing Child“, Spine, Vol 34, Nr 17, pp 1800-1807

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 Moramarco M and Weiss HR. (2015). Congenital Scoliosis, Curr Pediatr 2015 Nov 17

- ↑ Zhu X. et al. 2014, “Posterior hemivertebra resection and monosegmental fusion in the treatment of congenital scoliosis. “, Article from Annals of The Royal College of Surgeons of England, Vol 96, Nr5, pp. 41-44

- ↑ Musculoskeletal Key 25 Physiotherapy Available:https://musculoskeletalkey.com/25-physiotherapy/ (accessed 10.10.2021)

- ↑ COPAY A.G. et al.2008 “Minimum Clinically important difference in lumbar spine surgery patients: a choice of methods using the Oswestry Disability Index, Medical Outcomes Study Questionnaire Short Form 36, and Pain Scales“, The Spine Journal, vol. 8, nr. 6, p. 968 – 974, .

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 16.2 DEVIN C.J. and McGIRT M.J.2015, “Best evidence in multimodal pain management in spine surgery and means of assessing postoperative pain and functional outcomes“, Journal of Clinical Neuroscience, vol. 22, nr. 6, p. 930 – 938.

- ↑ 17.0 17.1 BOOS N. and AEBI M. (2008) Spinal Disorders, Fundamentals of Diagnosis and Treatment, Springer, p. 311, 434, 695-696