Sciatica

Introduction[edit | edit source]

Sciatica refers to radiating pain along the course of the sciatic nerve from the lower back or buttock to one or both legs or an associated lumbosacral nerve root.

A common mistake is referring to any low back pain or radicular leg pain as sciatica[1].

Sciatica is a clinical diagnosis based on the presence of radiating pain in one leg, with or without the associated neurological deficits of parasthesia and muscle weakness[2], which are the direct result of sciatic nerve or sciatic nerve root pathology.

Sciatica pain often is worsened with flexion of the lumbar spine, twisting, bending, or coughing[1].

Anatomy[edit | edit source]

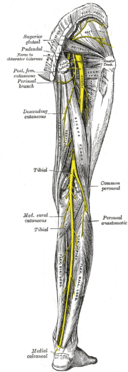

The sciatic nerve is made up of the L4 through S2 nerve roots which coalesce at the pelvis to form the sciatic nerve. At up to 2 cm in diameter, the sciatic nerve is easily the largest nerve in the body.

The sciatic nerve provides direct motor function to the hamstrings, lower extremity adductors, and indirect motor function to the calf muscles, anterior lower leg muscles, and some intrinsic foot muscles.

Indirectly through its terminal branches, the sciatic nerve provides sensation to the posterior and lateral lower leg as well as the plantar foot.

Etiology[edit | edit source]

Any condition that may structurally impact or compress the sciatic nerve may cause sciatica symptoms.

Sciatic nerve injury can also result in sciatica symptoms (such as pain, muscle weakness and paresthesia) and is usually caused by a traumatic injury (pressure, stretching or cutting), rather than compression or irritation of the nerve. Please read our sciatic nerve injury page for more information.

The causes of sciatica can be categorised into spinal or non-spinal causes or iatrogenic[3]:

Spinal causes:

- Spinal stenosis (due to degenerative bone disorders, trauma, inflammatory disease)

- Spondylolisthesis

- Herniated or bulging lumbar intervertebral disc

- Spinal or paraspinal mass (malignancy, epidural hematoma or abscess)[4]

Non Spinal causes:

- Piriformis syndrome

- Pregnancy

- Lumbar Radiculopathy

- Pelvic tumours

- Trauma to leg

Iatrogenic causes:

- Direct surgical trauma

- Faulty positioning during anaesthesia

- Injection of neurotoxic substances

- Tourniquets

- Dressings, casts or faulty fitting orthotics

- Radiation

Epidemiology[edit | edit source]

- Annual incidence of 1% to 5%[1]

- Lifetime incidence reported between 10% to 40%[1]

- No gender predominance[1]

- Peak incidence occurs in patients in their fourth decade[1]

- Rarely occurs before age 20 (unless traumatic)[1]

- No association with body height has been established except in the age 50 to 60 group[1]

- Increased incidence in those with poor general health (including presence of co-morbidities and smoking) and the presence of psychological factors such as depression[5]

- Physical activity increases incidence in those with prior sciatic symptoms and decreased in those with no prior symptoms[1].

- Occupational predisposition has been shown in machine operators, truck drivers, and jobs where workers are subject to physically awkward positions[4] or physical stress on the spine such as vibration[5]

Clinical Presentation[edit | edit source]

Patients with sciatica can present with neurological symptoms such as:

- Radicular pain in the distribution of the lumbosacral nerve root

- Sensory impairment/disturbance, such as hot and cold or tingling/ burning sensations in the legs or numbness

- Muscular weakness

- Reflex impairment

- Gait dysfunction

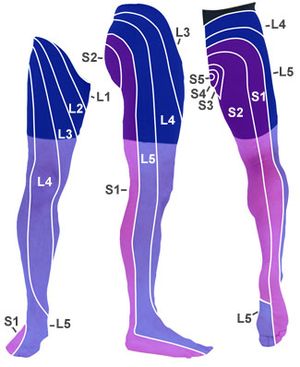

Sciatica symptoms of paresthesias or dysesthesias and oedema in the lower extremity can differ, depending on which nerve is affected[6][7]

- L4: When the L4 nerve is compressed or irritated, the patient feels pain, tingling and numbness in the thigh. The patient also feels weak when straightening the leg and may have a diminished knee jerk reflex.

- L5: When the L5 nerve is compressed or irritated, the pain, tingling and numbness may extend to the foot and big toes.

- S1: When the S1 nerve is compressed or irritated, the patient feels pain, tingling and numbness on the outer part of the foot. The patient also experiences weakness when elevating the heel off the ground and standing on tiptoes. The ankle jerk reflex may be diminished.

Differential Diagnosis[edit | edit source]

A thorough differential list is important in considering a diagnosis of sciatica and should include:

- Herniated lumbosacral disc

- Cauda Equina syndrome

- Muscle spasm

- Nerve root impingement

- Epidural abscess

- Epidural hematoma

- Tumor

- Potts Disease, also known as spinal tuberculosis

- Piriformis syndrome

Evaluation[edit | edit source]

Sciatica is most commonly diagnosed by:

History:

Complaints of radiating pain in the leg, which follows a dermatomal pattern[6]

- Pain generally radiates below the knee, into the foot[7]

- Patients complain about low back pain, which is usually less severe than the leg pain[6]

- Patients may also report sensory symptoms.

Special tests:

Clinicians should always look for and inquire about red flags when evaluating sciatica or in patients who present with any low back pain. Patients with signs of urinary retention or decreased anal sphincter tone should be urgently referred for investigation as this suggests cauda equina syndrome.

- Lasègue’s test

Also called as straight leg raising test (SLR) is the most commonly performed physical test for diagnosis of sciatica and lumbar disc hernia . The SLR is considered positive when it evokes radiating pain along the course of the sciatic nerve and below the knee between 30 and 70 degrees of hip flexion. Studies of its capacity to diagnose lumbar disc hernia show high sensitivity but low specificity.[8]

- Bragard test

Bragard test is a modification of the SLR, where ankle dorsiflexion is applied at the end of the SLR. Dorsiflexion reduces the SLR angle at which the test is positive and can be used to differentiate neural symptoms from musculoskeletal symptoms.[8]

Also known as the popliteal compression test or posterior tibial nerve stretch sign. The patient can be examined in sitting or in a supine position. The examiner flexes the knee and applies pressure on the popliteal fossa, evoking sciatica. Some examiners do it after SLRT by flexing the knee to relieve the buttock pain. The pain would be reproduced by a quick snap on the posterior tibial nerve in the popliteal fossa.[10]

Imaging:

It may be used if pain persists for more than 12 weeks or the patient develops progressive neurological deficits[2]

- Plain films of the lumbosacral spine may evaluate for fracture or spondylolisthesis

- Noncontrast CT scan may be performed to evaluate fracture if plain films are negative

- In cases where the neurologic deficit is the present or mass effect is suspected, immediate MRI is the standard of care in establishing the cause of the pain and ruling out pressing surgical pathology[4]

Outcome Measures[edit | edit source]

Many to choose from, below are but a few, all dependant on cause and assessment.

- Short Form-36 bodily pain (SF-36 BP)

- Oswestry disability index

- Roland-Morris disability index

- VAS-score: one of leg pain and one of back pain[12]

- McGill pain Questionnaire[12]: this questionnaire looks at the location, intensity, quality and pattern of the pain as well as alleviating and aggravating factors[13]

- TUG

- Tampa Scale for Kinesiophobia[14]

- Pain Catastrophising Scale[14]

Medical Management[edit | edit source]

Most patients improve over time with conservative treatment including exercise, manual therapy, and pain management[2]

- Pharmacology: a short course of oral NSAIDs; Opioid and non-opioid analgesics; muscle relaxants; anticonvulsants for neurogenic pain; localized corticosteroid injections.

- Surgical evaluation: to address structural abnormalities such as: disc herniation, epidural hematoma, epidural abscess or tumour may be considered if no improvement following 6-8 weeks of conservative treatment[2]. One study found that although it may speed up recovery, the effect is similar to conservative care at one year[2]

- Physical therapy management

Physical Therapy Management[edit | edit source]

In most cases of sciatica, conservative treatment is favoured. The evidence does not show that one treatment is superior to the other[15]

Patient Education: to include information on the nature of low back back, advice on self-management techniques and encouragement to continue normal activities[16]

Promote self management techniques such as:

- use of hot or cold packs for comfort and to decreased inflammation

- avoidance of inciting activities or prolonged sitting/standing

- Regularly changing position i.e. from sitting to standing

- practicing good erect posture

- use of proper lifting techniques

Exercise:

exercises to increase core strength, gentle stretching of the lumbar spine and hamstrings, regular light exercise such as walking, swimming, or aquatherapy

Manual therapy: spinal manipulation, mobilisation or soft tissue techniques such as massage - used alongside exercise and patient education[16]

Comprehensive treatment:

- Disc Herniation

- Lumbar Discogenic Pain

- Spinal Stenosis

- Degenerative Disc Disease

- Spondylolisthesis

- Piriformis Syndrome

- Sacroiliac Joint Dysfunction

- Sciatic Nerve Injury

- Corticosteroid injections

- Acupuncture

- Massage therapy

Concluding Remarks[edit | edit source]

There are many causes of sciatica and the disorder is best managed with a team of healthcare professionals that includes an orthopedic surgeon, physical therapist, neurologist, rehabilitation nurse, and a pain specialist.

- The key to sciatica is patient education.

- The majority of cases of sciatica are best managed conservatively.

- Patients should be encouraged by the clinician and nurse to lose weight, stop smoking and enroll in a physical therapy program.

- Bed rest should be limited.

- The pharmacist should caution the patient against the use of prescription-strength medications to avoid dependence and other adverse effects.

- Surgery should only be undertaken when conservative methods have failed.

- Regular exercise is essential[4]

Summary[edit | edit source]

The following video gives a summary of sciatica:

References[edit | edit source]

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 1.5 1.6 1.7 1.8 Davis D, Maini K, Vasudevan A. Sciatica. In: StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing, Treasure Island (FL); 2020. PMID: 29939685.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 2.4 Jensen RK, Kongsted A, Kjaer P, Koes B. Diagnosis and treatment of sciatica. BMJ. 2019 Nov 19;367:l6273.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 Osmosis. Sciatica. Available from: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=VYj-JfX0wT0 (last accessed 15.3.2019)

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 Davis DH, Wilkinson JT, Teaford AK, Smigiel MR. Sciatica produced by a sacral perineurial cyst. Tex Med. 1987 Mar;83(3):55-6.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 Parreira P, Maher CG, Steffens D, Hancock MJ, Ferreira ML. Risk factors for low back pain and sciatica: an umbrella review. Spine J. 2018 Sep;18(9):1715-1721.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 Koes BW, van Tulder MW, Peul WC. Diagnosis and treatment of sciatica. BMJ. 2007 Jun 23;334(7607):1313-7.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 Konstantinou K, Lewis M, Dunn KM. Agreement of self-reported items and clinically assessed nerve root involvement (or sciatica) in a primary care setting. Eur Spine J. 2012 Nov;21(11):2306-15.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 Kamath SU, Kamath SS. Lasègue’s sign. J Clin Diagn Res [Internet]. 2017 [cited 2023 Mar 27];11(5):RG01–2. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.7860/JCDR/2017/24899.9794

- ↑ Clinical Examination Videos. Straight leg raise test - Lasegue’s sign [Internet]. Youtube; 2017 [cited 2023 Mar 27]. Available from: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=JmvGHszR_X4

- ↑ Das JM, Nadi M. Lasegue Sign. StatPearls Publishing; 2022.

- ↑ CRTechnologies. Bowstring Test (CR). Available from: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=orb-VI51QF0&t=11s [last accessed 03.04.2023]

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 Brouwer PA, Peul WC, Brand R, Arts MP, Koes BW, van den Berg AA, van Buchem MA. Effectiveness of percutaneous laser disc decompression versus conventional open discectomy in the treatment of lumbar disc herniation; design of a prospective randomized controlled trial. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2009 May 13;10:49.

- ↑ Ngamkham S, Vincent C, Finnegan L, Holden JE, Wang ZJ, Wilkie DJ. The McGill Pain Questionnaire as a multidimensional measure in people with cancer: an integrative review. Pain Manag Nurs. 2012 Mar;13(1):27-51.

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 Monticone M, Ferrante S, Teli M, Rocca B, Foti C, Lovi A, Brayda Bruno M. Management of catastrophising and kinesiophobia improves rehabilitation after fusion for lumbar spondylolisthesis and stenosis. A randomised controlled trial. Eur Spine J. 2014 Jan;23(1):87-95.

- ↑ Luijsterburg PA, Verhagen AP, Ostelo RW, van Os TA, Peul WC, Koes BW. Effectiveness of conservative treatments for the lumbosacral radicular syndrome: a systematic review. Eur Spine J. 2007 Jul;16(7):881-99.

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE). Low back pain and sciatica in over 16s: assessment and management: NICE Guideline [NG59] 2016. Available from https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng59 [Accessed 13 Nov 2021]

- ↑ Physio Fitness | Physio REHAB | Tim Keeley. Treatment for lumbar spine disc bulge and sciatica - wk 1 | Feat. Tim Keeley | No.58 | Physio REHAB . Available from: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=4t8L4zHQ2nQ&t=7s [last accessed 03.04.2023]