Red Flags in Spinal Conditions

Original Editor - Anna Butler, Fiona Stohrer and Katherine Moon as part of the Nottingham University Spinal Rehabilitation Project

Top Contributors - Katherine Moon, Fiona Stohrer, Anna Butler, Admin, Kim Jackson, Rachael Lowe, Naomi O'Reilly, WikiSysop, Claire Knott, Jess Bell, Gunilla Buitendag, Tarina van der Stockt, Simisola Ajeyalemi, Shaimaa Eldib and 127.0.0.1

Introduction[edit | edit source]

Clinical findings that increase the level of suspicion that there is a serious medical condition presenting as common, non-serious, musculoskeletal conditions, are commonly described as red flags.[1]

International guidelines, for example the assessment of lower back pain[2] and neck pain,[3] recommend using red flags to identify serious pathology. Red flags are features from a patient's subjective and objective assessment which are thought to put them at a higher risk of serious pathology and warrant referral for further diagnostic testing[4]. They often highlight non-mechanical conditions or pathologies of visceral origin and can be contraindications to many Physiotherapy treatments.

Although red flags have a valid role to play in assessment and diagnosis they should also be used with caution as they have poor diagnostic accuracy[5] and red flag questions are not used consistently across guidelines[5]. Some guidelines even recommend immediate referral to imaging if any red flag is present, which could lead to many unnecessary referrals if clinicians did not clinically reason their referral[6]. The International Framework for Red Flags for Potential Serious Spinal Pathologies was developed to create some consensus amongst healthcare workers identifying possible red flags in patients presenting with musculoskeletal complaints.

See also Spinal Masqueraders

History of Red Flags[edit | edit source]

The role of Physiotherapists in identifying red flags has changed as Physiotherapists increasingly become the patients first point of contact with a healthcare professional. In McKenzies' 1990 book he states that “the patient once screened by the medical practitioner, should have any unsuitable pathologies excluded.” Within today’s healthcare system patients may not have even been seen by a doctor before they present to a Physiotherapist as there is more scope for self referral and private clinics. The term ‘red flag’ was first used by the Clinical Standards Advisory Group in 1994.[7] However, similar high risk markers date back to Mennell in 1952 and Cyriax in 1982.[8]

Epidemiology of Red Flags[edit | edit source]

It is hard to get an exact picture of the epidemiology of red flags as it depends heavily on the level of documentation by clinicians. One study of low back pain suggested that “the documentation of red flags was comprehensive in some areas (age over 50, bladder dysfunction, history of cancer, immune suppression, night pain, history of trauma, saddle anaesthesia and lower extremity neurological deficit) but lacking in others (weight loss, recent infection, and fever/chills)”[9].

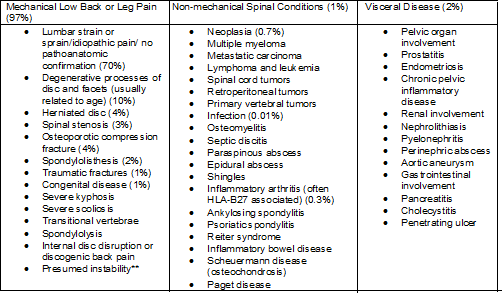

Table showing breakdown of the conditions lower back pain patients present with

Figures in brackets indicate estimated percentages of patients with these conditions among all adult patients with signs and symptoms of low back pain. Percentages may vary substantially according to demographic.[10]

Subjective Assessment[edit | edit source]

Clinicians must be aware of the key signs and symptoms associated with serious medical conditions that cause spinal pain and develop a system to continually screen for the presence of these conditions.[11] They should also consider the context of the red flag.[1] It is important to communicate clearly and effectively the reasons for asking these questions with the patient. Provide reassurance to the patient if they are likely at low risk for a serious pathology.

Age[edit | edit source]

In the UK, age above 55 years is considered a red flag, this is because above this age, particularly above 65, the chances of being diagnosed with many serious pathologies, such as cancers, increase[8].

History of Cancer[edit | edit source]

A patient history of cancer and also family history of cancer should be established, particularly in a first degree relative, such as a parent or sibling[8]. The most common forms of metastatic cancer are: breast, lung and prostate.

The most common warning signs of cancer are:

- Change in bowel or bladder habits

- Sores that do not heal

- Unusual bleeding or discharge

- Thickening or lump in breast elsewhere

- Indigestion or difficulty swallowing

- Obvious change in wart or mole

- Nagging cough or hoarseness

Unexplained Weight Loss[edit | edit source]

This should depend on a patient's previous weight and it is sometimes more useful to consider percentage weight loss. A weight loss of 5% or more within a 4 week period is a rough indicator of when unexplained weight loss should cause alarm[8].

Pain[8][edit | edit source]

- Constant Pain - This needs to be true constant pain that does not vary within a 24 hour period.

- Thoracic Pain - The thoracic region is the most common region for metastases.

- Severe Night Pain - This can be linked to be objective history if the patient's symptoms are brought on when they are lying down or non weight bearing.

- Abdominal pain and changed bowel habits but with no change of medication - A change is bowel habits can be a red flag for cauda equina.

Responsiveness to Previous Therapy[edit | edit source]

This can also be considered a yellow flag and should be taken with caution as many patients suffer episodic lower back and neck pain. However, patients who initially respond to treatment and then relapse may be a cause for concern[8].

Other[8] [edit | edit source]

- Systemically unwell

- Bilateral pins and needles

- Trauma , fall from height, road traffic accident or combat

- Past medical history of tuberculosis or osteoporosis

- Smoking - Has adverse effects on circulation, therefore decreasing the nutritional supply getting to the intervertebral disk and vertebrae. Over time this leads to degeneration of these structures and therefore instability which can cause lower back pain. It has also been suggested that regular coughing, which if often associated with smoking, can also lead to increased mechanical stress on the spine

- Cauda Equina Symptoms: urinary retention, fecal incontinence, unilateral or bilateral sciatica, reduced straight leg raise and saddle anaesthesia

Objective History [edit | edit source]

The subjective assessment will provide the therapist with the majority of the information needed to clarify cause of symptoms. [12] The objective assessment needs to be sufficiently thorough to ensure that if present, red flags are managed appropriately[13]. It is suggests that a total of 44 items in the objective examination can be considered as red flags[13]

Physical Appearance[edit | edit source]

The therapist should determine if the patient is unwell objectively however this is a very subjective concept. The following signs may indicate that the patient has a systemic serious pathology[8].

- Pallor/flushing

- Sweating

- Altered complexion: sallow/jaundiced

- Tremor/shaking

- Tired

- Disheveled/unkempt

- Halitosis

- Poorly fitting clothes

Deformity of the spine[edit | edit source]

Deformity of the spine with muscle spasm and severe limitation of movement are suggested to be key indicators of serious spinal pathology.[8] A rapid onset of a scoliosis may be indicative of an osteoma or osteoblastoma however this may not be apparent in standing. Physiological movements are often required to determine a rapid onset scoliosis. Some spinal tumors can be large enough to be seen or felt. Swelling and tenderness may be the first sign of a tumour.[8] It is also common for spinal tumours to limit physiological movements.

Muscle Spasm[edit | edit source]

This is suggested to be synonymous with spinal pain and is therefore difficult to determine if it is associated with a red flag pathology. If a serious spinal pathology is present, the muscle spasm may be severe enough to be a cause of scoliosis in the spine.[8] The correlation between muscle spasm, pain and other objective clinical measurements however, are poorly supported by strong evidence.[8]

Neurological Assessment[edit | edit source]

Patients who report neurological signs in the subjective assessment require a neurological assessment.[14] A neurological deficit is rarely the first presenting symptom in a patient with serious spinal pathology however 70% of patients will have a neurological deficit at the time of diagnosis.[8] Dermatomes, myotomes and reflexes should be examined. The upper motor neuron pathways should also be examined via extensor plantar reflex (Babinski), clonus and hoffmans. If brisk, it may indicate a upper motor neuron pathology.[8]

Diagnostic Tests[edit | edit source]

In differential diagnosing serious spinal conditions we should understand the best tests for each spinal pathology and/or clusters of tests. The best tests are: reliable, low cost, have validated findings and high diagnostic accuracy i.e. specifictit and sensitivity).

- Specificity - Is the percentage of people who test negative for a specific disease among a group of people who do not have the disease [15]

- Sensitivity - Is the percentage of people who test positive for a specific disease among a group of people who have the disease [15]

- Likelihood ratio = The Likelihood Ratio (LR) is the likelihood that a given test result would be expected in a patient with the target disorder compared to the likelihood that that same result would be expected in a patient without the target disorder [16]

- High sensitivity and LOW LR = RULE OUT people who don’t have the disease

- High specificity and HIGH LR = RULE IN people who have the disease

Fracture[edit | edit source]

Lumbar Spine[edit | edit source]

Table to show sensitivity, specificity, and likelihood ratios of subjective information in the diagnosis of lumbar fracture[17][18][19][20][21][22][23]

| Subjective Index | Sensitivity (%) | Specificity (%) | Positive likelihood Ratios (%) | Negative likelihood Ratios (%) |

|

History of major trauma |

0.65 0.36 1 |

0.95 0.90 0.51 |

12.8 3.42 1.93 |

0.37 0.72 0.12 |

| Pain and tenderness | 0.60 | 0.91 | 6.7 | 0.44 |

| Tenderness |

0.50 0.72 |

0.73 0.59 |

1.88 1.76 |

0.68 0.47 |

| Age >50 years |

0.79 0.79 |

0.64 0.64 |

2.2 2.16 |

0.34 0.34 |

| Age >52 | 0.95 | 0.39 | 1.55 | 0.13 |

| Female |

0.47 0.72 |

0.80 0.43 |

2.3 1.26 |

0.67 0.65 |

| Corticosteroid use |

0.06 0 |

0.99 0.99 |

12.0 3.97 |

0.94 0.97 |

| Clustered Results | Sensitivity (%) | Specificity (%) | Positive likelihood Ratio (%) | Negative likelihood ratio (%) |

| 1 of 5 | 0.97 | 0.06 | 1.04 | 0.43 |

| 2 of 5 | 0.95 | 0.34 | 1.43 | 0.16 |

| 3 of 5 | 0.76 | 0.69 | 2.45 | 0.34 |

| 4 of 5 | 0.37 | 0.96 | 9.62 | 0.66 |

| 5 of 5 | 0.03 | 1 | 7.63 | 0.98 |

To objectively test for a compression fracture in the lumbar spine the examiner stands behind the patient. The patient stands facing a mirror so that the examiner can gauge their reaction. The entire length of the spine is examined using firm, closed-fist percussion. It is positive when the patient complains of a sharp, sudden pain.

| Diagnostic Test |

Sensitivity (%) |

Specificity (%) |

Positive Likelihood ratio (%) |

Negative Likelihood Ratio (%) |

| Percussion Test |

87.5 |

90.0 |

8.8 |

0.14 |

Cervical Spine[edit | edit source]

In the cervical spine the Canadian C-Spine Rule can be used to identify when people should be sent for radiography.

Cancer[edit | edit source]

Shows sensitivity, specificity and likelihood ratios for signs and symptoms that could indicate cancer [24][25][26][27][28][29]

| Subjective Index |

Sensitivity (%) |

Specificity (%) |

Positive likelihood ratio (%) |

Negative likelihood ratio (%) |

| Age >50 |

0.77 0.75 0.50 1 0.55 |

0.71 0.70 0.74 0.41 0.35 |

2.5 1.92 1.66 0.86 |

0.36 0.68 0.06 1.27 |

| Previous history of cancer |

0.31 0.31 1 |

0.98 0.98 0.97 |

15.27 31.67 |

0.71 0.06 |

| Failure to improve in one month of therapy |

0.31 0.31 |

0.90 0.90 |

3.08 |

0.77 |

| No relief from bed rest |

>0.90 | 0.46 | ||

| Duration more than one month |

0.50 0.50 |

0.81 0.81 |

2.63 |

0.62 |

| Unexplained weight loss |

0.15 | 0.94 | 2.59 | 0.90 |

Ankylosing Spondylitis[edit | edit source]

Shows sensitivity and specificity of information from subjective assessment in regards to Ankylosing Spondylitis [25]

| Subjective Index |

Sensitivity (%) |

Specificity (%) |

| Age of onset <40 |

1.00 |

0.07 |

| Pain not relieved by supine |

0.80 |

0.49 |

| Morning back stiffness |

0.64 |

0.59 |

| Pain duration >3 months |

0.71 |

0.54 |

| Chest expansion < or equal to 2.5cm |

0.09 |

0.99 |

| 4 out of 5 of the above |

0.23 |

0.82 |

Cauda Equina[edit | edit source]

Shows sensitivity and specificity of the signs and symptoms associated with cauda equina[30][31].

| Subjective Index | Sensitivity (%) | Specificity (%) |

| Rapid symptoms within 24 hours | 0.89 | |

| History of back pain | 0.94 | |

| Urinary Retention | 90 | |

| Loss of sphincter tone | 80 | |

| Sacral sensation loss | 85 | |

| Lower extremity weakness or gait loss | 84 | |

| Abnormal anal tone | 1 | 0.95 |

| Altered perineal sensation | 1 | 0.67 |

Clinical Reasoning[edit | edit source]

The use of red flags should not replace clinical reasoning but used as an adjunct to the process.[32] A lone red flag would not necessarily provide a strong indication of serious pathology. It should be considered in the context of a person's history and the findings on examination.[33][34]

Patients’ inappropriate misattribution of insidious symptoms to a traumatic event is common and can be misleading. Clinical reasoning is only as good as the information on which it is based indicating the importance of thorough questioning in the subjective assessment.

The three types of errors that can occur in clinical reasoning include:

- Faulty perception or elicitation of cues

- Incomplete factual knowledge

- Misapplication of known facts to a specific problem

Within the clinical reasoning process, the therapist should determine if there are logical inferences in regards to the information they are receiving from the patient. The therapist should not be reassured by previous investigations being reported on as normal. In the early stages, serious spinal pathology is difficult to detect and weight loss will not always be evident in these early stages.[35]

Red Herrings for serious spinal pathology may include spinal stenosis, lower limb edema, nerve root compression, peripheral neuropathy, cervical myelopathy, alcoholism, diabetes, MS and UMND.[13] Due to the abundance of red herrings that can be present, it is important the therapist interprets the red flags in the context of the patient's current presenting condition and not singularly.[13]

Management of Red Flags[edit | edit source]

If red flags are identified in the spine, the should first consider if onward referral is appropriate.[36] If serious enough, the therapist may refer to Accident and Emergency such as in the case of cauda equina syndrome and fractures.[37] Otherwise further specialist medical opinions can be gained,[38] this may be referral onto a specialist spinal clinic.[38]

Failure to improve after one month is a red flag and the patient can be referred back to the GP for continued management and further diagnostic tests as required.[8] The GP will be able to refer the patient on to have x-rays, CT/MRI, blood tests or nerve conduction studies.[39] It has been suggested that to reduce the rate of false alarms, the patient should be referred back to the GP in the first instance to undertake further investigations as required before more advanced imaging is undertaken[40].

Documentation[edit | edit source]

After onward referral red flags must be acknowledged in the notes as this will indicate contraindication to physiotherapy. Physiotherapist documentation of red flags in the USA has demonstrated that 8 of 11 red flags were documented 98% of the time as seen below:

- Age over 50

- Bladder dysfunction

- History of cancer

- Immunosuppression

- Night pain

- History of trauma

- Saddle anaesthesia

- Lower extremity neurological deficit

Red flags that were not documented routinely included:[38]

- Weight loss

- Recent infection

- Fever/chills

In comparison to this data in the USA, Scotland undertook a review of the documentation of red flags on 2147 episodes of care. The investigation took place in two phases, between May and June 2008 and January and February 2009). The therapists were given an online tool to prompt them in respect to the most common red flags [32] Results reported that in the first phase, 33% of red flags were documented and of those 33%, 54% were cauda equina symptoms. In comparison, within phase two, the rate of documentation rose to 65% for red flags and within those, 84% recorded cauda equina [32]. Despite documentation improving, this still left 1 in 5 therapists not documenting red flags. Of all the red flag questions investigated, HIV/drug abuse was the least documented red flag [32]

References[edit | edit source]

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Finucane L. An Introduction to Red Flags in Serious Pathology. Plus2020.

- ↑ Koes B, van Tulder M, Lin C, Macedo L, McAuley J, Maher C. An updated overview of clinical guidelines for the management of non-specific low back pain in primary care. European Spine Journal. 2010;19(12):2075-94.

- ↑ Childs, J.D., Cleland, J.A., Elliott, J.M., Teyhen, D.S., Wainner, R.S., Whitman, J.M., Sopky, B.J., Godges, J.J., Flynn, T.W., Delitto, A. and Dyriw, G.M., 2008. Neck pain: clinical practice guidelines linked to the International Classification of Functioning, Disability, and Health from the Orthopaedic Section of the American Physical Therapy Association. Journal of Orthopaedic & Sports Physical Therapy, 38(9), pp.A1-A34.

- ↑ Henschke N, Maher C, Ostelo R, de Vet H, Macaskill P, Irwig L. Red flags to screen for malignancy in patients with low-back pain. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2013(2).

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 Premkumar A, Godfrey W, Gottschalk MB, Boden SD. Red Flags for Low Back Pain Are Not Always Really Red. J Bone Jt Surg. 2018;100(5):368–74.

- ↑ Downie A, Williams C, Henschke N, Hancock M, Ostelo R, de Vet H, et al. Red flags to screen for malignancy and fracture in patients with low back pain: systematic review. British Medical Journal. 2013;347.

- ↑ Gordon Higginson. Clinical Standards Advisory Group. Qual Health Care. 1994 Jun; 3(Suppl): 12–15.

- ↑ 8.00 8.01 8.02 8.03 8.04 8.05 8.06 8.07 8.08 8.09 8.10 8.11 8.12 8.13 8.14 Greenhalgh, S. and Selfe, J. Red Flags: A guide to identifying serious pathology of the spine. Churchill Livingstone: Elsevier. 2006.

- ↑ Leerar, P J, Boissonnault, W, Domholdt, E and Roddey, T. Documentation of red flags by physical therapists for patients with low back pain. The Journal of Manual and Manipulative Therapy. 2007; 15 (1): 42 – 49.

- ↑ Deyo, R and Diehl, A. Cancer as a cause of back pain – fequencey, clinical presentation and diagnostic strategies.Journal of General Internal Medicine. 1988;3(3):230-8.

- ↑ Anthony Delitto, Steven Z. George, Linda Van Dillen, Julie M. Whitman, Gwendolyn Sowa, Paul Shekelle, Thomas R. Denninger, Joseph J. Godges. Low Back Pain: Clinical Practice Guidelines Linked to the International Classification of Functioning, Disability, and Health from the Orthopaedic Section of the American Physical Therapy Association. Journal of Orthopaedic and Sports Physical Therapy, 2012, 42(4)

- ↑ Eveleigh, C. Red Flags and Spinal Masquereders. [online]. Available at : www.nspine.co.uk/.../09-nspine2013-red-flags-masqueraders.ppt. Accessed 13/01/14. 2013.

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 13.2 13.3 Greenhalgh, S. and Selfe, J. A qualitative investigation of Red Flags for serious spinal pathology. Physiotherapy. 95, pp: 223 – 226. 2009.

- ↑ Petty, N. J. and Moore, A. P. Neuromuscular examination and assessment: a handbook for therapists. Edingburgh: Churchill Livingstone. 2001.

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 Sackett, D.L., Straws, S.E., Richardson, W.S., et al. (2000) Evidence-based medicine: How to practice and teach EBM.(2nd ed.) London: Harcourt Publishers Limited.

- ↑ Centre for evidence based medicine, Critical appraisal, Likelihood ratios, August 2012, (accessed January 2014)

- ↑ Van den Bosch MAAJ, Hollingworth W, Kinmonth AL, Dixon AK. Evidence against the use of lumbar spine radiography for low back pain. Clinical Radiology 2004;59:69-76.

- ↑ Roman M, Brown C, Richardson W,Isaacs R, Howes C, Cook C. The development of a clinical decision making algorithm for detection of osteoporotic vertebral compression fracture or wedge deformity. Journal Manipulative Physiological Therapeutics 2010;18:44-9.

- ↑ Patrick JD, Doris PE, Mills ML, Friedman J, Johnston C. Lumbar spine x-rays: a multihospital study. Annals Emergency Medicine 1983;12:84-7.

- ↑ Scavone JG, Latshaw RF, Rohrer GV. Use of lumbar spine films. Statistical evaluation at a university teaching hospital. JAMA 1981;246:1105-8.

- ↑ Gibson M, Zoltie N. Radiography for back pain presenting to accident and emergency departments. Archives Emergency Medicine 1992;9:28-31.

- ↑ Deyo RA, Diehl AK. Lumbar spine films in primary care: current use and effects of selective ordering criteria. Journal General Internal Medicine 1986;1:20-5.

- ↑ Langdon J, Way A, Heaton S, Bernard J, Molloy S. Vertebral compression fractures: new clinical signs to aid diagnosis. Annals Royal College Surgeons England 2009 Dec 7.

- ↑ Reinus WR, Strome G, Zwemer FL. Use of lumbosacral spine radiographs in a level II emergency department. AJR American Journal Roentgenology 1998;170:443-7.

- ↑ 25.0 25.1 Deyo RA, Jarvik JG. Diagnostic evaluation of low back pain with emphasis on imaging. Ann Intern Med. 2002;137:586-97.

- ↑ Jacobson AF. Musculoskeletal pain as an indicator of occult malignancy. Yield of bone scintigraphy. Archives of International Medicine 1997;157:105-9.

- ↑ Frazier LM, Carey TS, Lyles MF, Khayrallah MA, McGaghie WC. Selective criteria may increase lumbosacral spine roentgenogram use in acute low-back pain. Archives of International Medicine 1989;149:47-50.

- ↑ Deyo RA, Diehl AK. Cancer as a cause of back pain: frequency, clinical presentation, and diagnostic strategies. Journal General Internal Medicnie 1988;3:230-8.

- ↑ Cook C, Ross MD, Isaacs R, Hegedus E. Investigation of nonmechanical findings during spinal movement screening for identifying and/or ruling out metastatic cancer. Pain Practice 2012;12:426-33.

- ↑ Jalloh and Minhas. Emergency Medicine. 2007;24:33-4

- ↑ N.A. Johnson and S. Grannum. Accuracy of clinical signs and symptoms in predicting the presence of cauda equine syndrome The Bone and Joint Journal. 2012 vol. 94-B no. SUPP X 058

- ↑ 32.0 32.1 32.2 32.3 Ferguson, F. Holdsworth, L. and Rafferty, D. Low back pain and physiotherapy use of red flags: the evidence from Scotland. Physiotherapy. 96, pp: 282 – 288. 2010

- ↑ Finucane L, Selfe J, Mercer C, Greenhalgh S, Downie A, Pool A et al. An evidence informed clinical reasoning framework for clinicians in the face of serious pathology in the spine course slide. Plus2020.

- ↑ Mercer, C., Jackson, A., Hettinga, D., Barlos, P., Ferguson, S., Greenhalgh, S., Harding, V., Hurley Osing, D., Klaber Moffett, J., Martin, D., May, S., Monteath, J., Roberts, L., Talyor, N. and Woby, S. Clinical guidelines for the physiotherapy management of persistent low back pain, part 1: exercise. Chatered Society of Physiotherapy. [online]. Available at: http://www.csp.org.uk/publications/low-back-pain. Accessed 13/01/14. 2006.

- ↑ Greenhalgh, S. and Selfe, J. Malignant Myeloma of the spine: Case Report. Physiotherapy. 89 (8), pp: 486 – 488.

- ↑ Moffett, J. K., McLean, S. and Roberts, L. Red flags need more evalutation: reply. Rheumatology. 45, pp: 922. 2006

- ↑ Chau, A. M. T., Xu, L. L., Pelzer, N. R. and Gragnaniello, C. (2013). Timing of surgical intervention in cauda equine syndrome – a systematic critical review. World Neurosurgery. 12

- ↑ 38.0 38.1 38.2 Carvalho, A. Red Alert: How useful are flags for identifying the origins of pain and barriers to rehabilitation? Frontline. 13 (17). 2007

- ↑ Chartered Society of Physiotherapy. The Clinical Guidelines for the physiotherapy management of perisistent low back pain. [online]. Available at: www.csp.org.uk/publications/low-back-pain. Accessed 14/01/2014. 2006

- ↑ Hensche, N. and Maker, C. Red flags need more evaluation. Rheumatology. 45, pp: 921. 2006.