Total Knee Arthroplasty: Difference between revisions

Safiya Naz (talk | contribs) mNo edit summary |

Safiya Naz (talk | contribs) mNo edit summary |

||

| Line 204: | Line 204: | ||

* Ambulation goals are achieved | * Ambulation goals are achieved | ||

* Compliance and competency with a home exercise program is achieved | * Compliance and competency with a home exercise program is achieved | ||

* Recommend commitment to an independent exercise program over 6-12 months post-operatively, with strength training 2-3 times/ week, to ensure hypertrophy beyond neural adaptation <ref name=":9" /> | |||

== Complications & Contraindications == | == Complications & Contraindications == | ||

Revision as of 17:18, 30 December 2020

Original Editors - Lynn Wright

Top Contributors - Safiya Naz, Loes Verspecht, Kim Jackson, Kun Man Li, Lucinda hampton, Jess Bell, Ellen Wynant, Lisa Ingenito, Claire Knott, George Prudden, Karolien Van Melkebeke, Lynn Wright, Tarina van der Stockt, Lauren Lopez, Ewa Jaraczewska, Greg Walding, Daniele Barilla, WikiSysop, Karen Wilson, Famke Coosemans, Leana Louw, 127.0.0.1 and Evan Thomas

Definition/Description[edit | edit source]

Total knee arthroplasty (TKA) or total knee replacement (TKR) is common orthopaedic surgery that involves replacing the articular surfaces (femoral condyles and tibial plateau) of the knee joint with smooth metal and polyethylene plastic. [1][2] TKA aims to improve the quality of life of individuals with end-stage osteoarthritis by reducing pain and increasing function[1].The number of TKA operations has increased in developed countries,[3] with younger patients receiving TKA[4].. There is at least one polyethylene piece, placed between the tibia and the femur, as a shock absorber.[5] In 50% of the cases the patella is also replaced. Reasons for a patella replacement include: osteolysis, maltracking of the patella, failure of the implant. The aim of the patella reconstruction is to restore the extensor mechanism. The level of bone loss will dictate which kind of patella prosthesis is placed.

The prostheses are usually reinforced with cement, but may be left uncemented where bone growth is relied upon to reinforce the components. The patella may be replaced or resurfaced[6][7], During surgery, a quadriceps-splitting or a quadriceps-sparing approach may be used[8] and the cruciate ligaments may be excised or preserved.

There are different types of surgical approaches, design, and fixations[5][9] A unicondylar knee replacement (UKR), [10] patellofemoral replacement (PFR) may also be performed depending on extent of disease. [1]

Several options of anaesthesia are available and include: regional anaesthesia in combination with local infiltration anaesthesia, or general anaesthesia in combination with local infiltration anesthesia, with possible addition of peripheral nerve blocks to either option[11] A tourniquet may sometimes be used during surgery[12].Computer-assisted navigation systems have been introduced in TKA surgery, and prospective studies on long term functional outcomes are needed[13].

The main clinical reason for the operation is osteoarthritis with the goal of reducing an individuals pain and increasing function.[14]

Clinically Relevant Anatomy[edit | edit source]

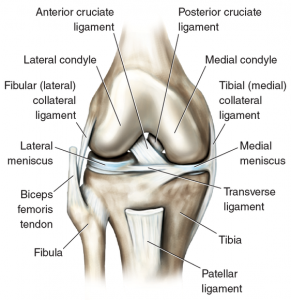

The Knee is a modified hinge joint, allowing motion through flexion and extension, but also a slight amount of internal and external rotation. There are three bones that form the knee joint: the upper part of the Tibia , the lower part of the Femur and the Patella. The bones are covered with a thin layer of cartilage, which ensures that friction is limited. On both the lateral and medial sides of the tibial plateau, there is a meniscus, which adheres the tibia and has a role as a shock absorber. The knee joint is reinforced by ligaments and a joint capsule.

.

Epidemiology /Etiology[edit | edit source]

- When all the compartments of the knee are damaged, a total knee prosthesis may be necessary.

- The most common reason for a total knee prosthesis is osteoarthritis.[15] Osteoarthritis causes the cartilage of the joint to become damaged and no longer able to absorb shock.

- There are a lot of external risk factors that can cause knee osteoarthritis. For example: being overweight; previous knee injuries; partial removal of a meniscus;[16] rheumatoid arthritis; fractures; congenital factors.

- There might also be some genetic factors the contribute to the development of osteoarthritis, but more research is necessary.

- Total knee arthroplasty is more commonly performed on women and incidence increases with age.[16] Pain is the main complaint of patients' with knee osteoarthritis. Pain is subjective, involves peripheral and central neural mechanisms that are modulated by neurochemical, environmental, psychological and genetic factors.

- Total knee arthroplasty is more commonly performed on women and individuals of older ages.[17][18]In both the US and UK, majority of TKA surgeries were performed on women[17][19] Dramatic increases in TKA surgeries are projected to occur[17], with an increasing rate of younger TKA recipients under the age of 60[20].

- IN the US in 2008 63% of TKR operations were on women.

- Also a dramatic increase in TKR surgery is projected to occur with a 673% increase by 2030 in America.[21]

- Another trend for TKR surgery is the increasing rate of of recipients under 60, whilst initially designed as an operation for the >70 age bracket.[22]

Characteristics/Clinical Presentation[edit | edit source]

- Pain is the main complaint of patients' with degenerated knee joints.

- At first, pain is felt only after rest periods (this is also called ‘starting pain’) after a couple of minutes the pain slowly fades away.

- When the knee joint degeneration increases, the pain can also occur during rest periods and it can affect sleep at night.

- Individuals' can also complain of knee stiffness and crepitus.

- Due to pain and stiffness, function can decline and is manifests as reduced exercise tolerance, difficulty climbing stairs or slopes, reduced gait speed and increased risk of falls.

Complications[edit | edit source]

Stiffness is the most common complaint following primary total knee replacement, affecting approximately 6 to 7% of patients undergoing surgery.[23] *0 5 of patients have some degree of movement limitation.[21] In addition to stiffness, the following complications can impact on function following this surgery:

- Loosening or fracture of the prosthesis components

- Joint instability and dislocation

- Infection

- Component misalignment and breakdown

- Nerve damage

- Bone fracture (intra or post operatively)

- Swelling and joint pain

Complications as above may require joint revision surgery to be performed.

Diagnostic Procedures[edit | edit source]

- Before a TKA surgery, a full medical evaluation is performed to determine risks and suitability.

- As part of this evaluation, imaging is used to assess the severity of joint degeneration and screen for other joint abnormalities[24].

- A knee radiograph is performed to check for prosthetic alignment before closure of the surgical incision.[7]

- In order to assess the gravity of wear or injury the orthopedic surgeon carries out external tests, and the patient is likely to undergo imaging.

- Patients co-morbidities also need to be considered.[25]

- Obesity is an important factor that needs to be considered prior to surgery as evidence suggests a correlation between higher body mass index (BMI) and poorer post-operative functional outcomes.[26]

Different stages of knee osteoarthritis on X-rays.

Examination[edit | edit source]

Subjective Assessment[edit | edit source]

First the examiner should ask the patient about the history of complaints and also about expectations from surgery.

The examiner should then perform a full objective examination. After this different tests could be carried out to determine whether the patient needs total knee arthroplasty:

- Active ROM

- Passive ROM

- Muscle power

- Functional tasks

Post-operative Tests[edit | edit source]

- Inspection: of the wound/scar, redness, adhesion of the skin. When infection of the wound is suspected the patient must be referred to an Orthopedic Consultant or an emergency doctor.

- Palpation: post-operative swelling, hypertonia (adductors), pain and warmth.[27]

Medical Management[edit | edit source]

The purpose of the surgical procedure is to achieve pain free movement again, with full functionality of the joint, and to recreate a stable joint with a full range of motion.

Total knee arthroplasty is chosen when the patient has serious complaints and functional limitations. Surgery takes some 60-90 minutes and involves putting into place a three-part prosthesis: a part for the femur, a part for the tibia, a polyethylene shock absorbing disc and sometimes a replacement patella. A high comfort insert design is chosen to achieve this. The perfect prosthesis doesn’t exist; every prosthesis must be different and the most appropriate size and shape is chosen on a patient by patient basis.

During surgery a tourniquet is sometimes used; this will ensure that that there is less blood loss. However, when a tourniquet is not used, there will be less swelling and less pain.[12]

Physiotherapy Management[edit | edit source]

Pre-operative[edit | edit source]

- The physical therapist can choose to teach the patient the exercises before surgery in order that the patient might understand the procedures and, after surgery, be immediately ready to practice a correct version of the appropriate exercises.

- Pre-operative exercises may be taught before surgery, so that patients may perform the appropriate exercises more effectively immediately after TKA surgery.

- A pre-operative training programme may also be used to optimize functional status of patients to improve post-operative recovery.[28]

- It is also important that the functional status of the patient before surgery is optimised to assist recovery. The focus of a pre-operative training program should be on postural control, functional lower limb exercises and strengthening exercises for both of lower extremities.[28]

- Evidence supporting the efficacy of pre-operative physiotherapy on patient outcome scores, lower limb strength, pain, range of movement or hospital length of stay following total knee arthroplasty is lacking.[29][30][31][32]

- Pre-operative exercises may be taught before surgery, so that patients may perform the appropriate exercises more effectively immediately after TKA surgery.

- A pre-operative training programme may also be used to optimize functional status of patients to improve post-operative recovery. [28]

Post-operative[edit | edit source]

- Evidence indicates that physiotherapy is always beneficial to the patient post-operatively following total knee arthroplasty.

- Although specificity of intervention can vary, the benefits of the patient actively participating and moving under physiotherapists' direction are clear and supported by the evidence.

- There is also some low-level evidence that accelerated physiotherapy regimens can reduce acute hospital length of stay.[33]

- Perhaps the most important role of physiotherapists in the management of patients following TKA is facilitating mobilisation within 48 hours of surgery, sometimes as early as the same day as the operation (Day 0).

- The use of a continuous passive motion (CPM) may be utilised in this period. A 2011 report found that although clinical outcome measure showed no better results than traditional mobilisation techniques, subjectively patient outcomes of pain, joint stiffness and functional activity were better.[34]

- The optimal physiotherapy protocol should also include strengthening and intensive functional exercises given through land-based or aquatic programs, that are progressed as the patient meets clinical and strength milestones. Due to the highly individualized characteristics of these exercises the therapy should be under supervision of of a trained physical therapist for best results.[35][36]

- There is evidence that cryotherapy improves knee range of motion and pain in the short-term. With are relatively small sample size of low quality evidence, it is difficult to draw solid conclusions regarding the outcomes measured and specific recommendations cannot be made about the use of cryotherapy.[37]

- Majority of individuals begin physiotherapy during their inpatient stay, within 24 hours after TKA surgery, which typically lasts 1 to 2 hours. [24]

- Range of motion and strengthening exercises, cryotherapy and gait training are typically initiated, and a home exercise programme prescribed before discharge from hospital. There is low-level evidence that accelerated physiotherapy regimens reduce acute hospital length of stay[33].

- Patients are usually discharged after a few days’ stay in hospital and receive follow-up physiotherapy in the outpatient or home care setting within 1 week.

The following post-operative guidelines for assessment and management are intended for individuals who have undergone primary TKA surgery with cemented prosthesis, using a standard surgical approach. Surgeons’ instructions should always be followed[38].

Post-Operative Examination[edit | edit source]

Subjective Assessment[edit | edit source]

Assessment should include, and is not limited to:

Operative and post-operative complications, if any

- History of knee and other musculoskeletal complaints, if any

- Past medical history and relevant comorbidities

- Social factors and home set-up

- Progress in home exercises post-TKA surgery

- Pain and other symptoms/ discomfort (e.g. numbness, swelling)

- Expectations from surgery and rehabilitation

- Specific functional goals

Objective Assessment[edit | edit source]

Assessment should include, and is not limited to:

- Observation of surgical wound or scar

- Assess for signs of infection: redness, discharge (pus/ odour), adhesions of the skin, abnormal warmth and swelling, expanding redness beyond the edges of the surgical incision, fever or chills. Suspicion of infection warrants medical referral.

- Knee swelling (circumference)

- Vital signs and relevant laboratory findings (in the acute setting

- Check for deep vein thrombosis (DVT):

- Homan’s sign test

- Signs and symptoms of chest pain, shortness of breath, redness or discoloration, heat, deep calf pain or tenderness

- Suspicion of DVT warrants urgent medical referral

- Palpation: Check for increased warmth and swelling, as well as muscle activation (e.g. quadriceps; vastus medialis oblique) and hypertonia (e.g. adductors)

- Lower limb range of motion: Active and passive knee range of motion (see treatment milestones for more details) in supine or semi-reclined position

- Lower limb muscle activation and strength

- Gait

- Timed up and Go (TUG) or 10-metre walk test may be used, depending on individuals’ ability and tolerance

- Assess for guarding in knee flexion, avoidance to weight bear on operative leg, antalgic patterns etc.

Outcome Measures[edit | edit source]

- Oxford Knee Score [39][40]

- Patient satisfaction [41]

- Walking tests: Timed Get Up and Go Test (TUG),

- Six minute walking test [39]

- Visual Analogue Scale (VAS)

- Western Ontario and McMaster Universities Osteoarthritis Index score (WOMAC) [39][41]

- Knee disability and Osteoarthritis Outcome score (KOOS)

- Timed Get Up and Go Test (TUG)

- Visual Analogue Scale (VAS)

- Range of motion (ROM)[39]

Treatment Strategies & Goals[edit | edit source]

Phase I: Up to 2-3 weeks post-surgery[42][38][edit | edit source]

- Patient education: pain science, pain management, importance of home exercises and setting rehabilitation expectations

- Achieve active and passive knee flexion to 90 degrees with full extension

- Keep passive knee flexion range of motion testing to <90 degrees in the first 2 weeks to protect surgical incision and respect tissue healing

- Minimal pain and swelling

- Achieve full weight bearing

- Independence in mobility and activities of daily living

During the early phase of rehabilitation, it is important to establish a therapeutic alliance and provide education on pain management strategies. Pain education may include appropriate usage of pain medication, cryotherapy [43] and elevation of the operated limb. Patients should be informed to avoid resting with a pillow under the knee as this may lead to contractures.

There is evidence that cryotherapy improves knee range of motion and pain in the short-term. Icing after exercise may be helpful, but low quality evidence makes specific recommendations for the use of cryotherapy difficult. [44]

Reviewing the patient’s home exercise program (HEP) is also important to do on Day 1. Engaging in their home exercise program is a critical piece of their recovery. Review their post-op exercises given from the surgeon and inpatient Physiotherapist (Sunnybrook Hospital5 has a great resource). In the early phase, stair climbing with the non-operated leg leading on ascent, and the operated leg leading on descent may be encouraged.

Common Bed and Chair Exercises[edit | edit source]

- Ankle plantarflexion/dorsiflexion

- Isometric knee extension in outer range

- Inner Range Quadriceps strengthening using a pillow or rolled towel behind the knee

- Knee and hip flexion/extension

- Isometric buttock contraction

- Hip abduction/adduction

- Straight leg raises

- Bridging

Phase II: 4-6 weeks post-surgery[edit | edit source]

- No quadriceps lag, with good, voluntary quadriceps muscle control

- Active knee flexion range of motion to 105 degrees

- Full knee extension

- Minimal to no pain and swelling

Physiotherapy sessions may be scheduled once to twice weekly, at six to twelve weeks post-TKA surgery. This frequency may increase or decrease depending on individuals’ progress. Achieving full knee extension is essential for functional tasks such as walking and stair climbing. Knee flexion range of motion is required for comfortable walking (65 degrees), stair climbing (85 degrees), sitting and standing (95 degrees)[23] In this phase, tissue mobilization techniques may be used to improve scar mobility.

Phase III: 6-8 weeks post-surgery[edit | edit source]

- Strengthening and functional exercises

- Balance and proprioception training

While primary TKA has been reported to reduce falls incidence [43]and improving balance-related functions such as single limb standing balance [46],[43] the suboptimal recovery of proprioception, sensory orientation, postural control, and strength of the operated limb post-TKA is well documented, [47][46][43]. Literature highlights the importance of proprioceptive training, and pre-operative training [47] that involves the non-operated limb [46] may be considered. Balance exercises may include single leg balance, stepping over objects, lateral step-ups, and standing on uneven surfaces. Balance and proprioceptive training that involves single limb standing may begin when adequate knee control is achieved, which typically occurs around 8 weeks post-TKA. [38]

Individualized rehabilitation programs that include strengthening and intensive functional exercises given through land-based or aquatic programs may be progressed as clinical and strength milestones are met. Supervision by a trained physiotherapist is beneficial, owing to the highly individualized characteristics of these exercises. [ [36][35]

Phase IV: 8-12 weeks, up to 1 year post-surgery[edit | edit source]

- Independent exercise in community setting

- Continue regular exercise involving strengthening, balance and proprioception

- Incorporate strategies for behavior change to increase overall physical activity [48]

Discharge Criteria[edit | edit source]

Discharge planning should be individualized to consider if:

- A minimum of 110 degrees active knee flexion and full extension is achieved

- Ambulation goals are achieved

- Compliance and competency with a home exercise program is achieved

- Recommend commitment to an independent exercise program over 6-12 months post-operatively, with strength training 2-3 times/ week, to ensure hypertrophy beyond neural adaptation [38]

Complications & Contraindications[edit | edit source]

Following TKA surgery, these complications may occur:

- Deep vein thrombosis (DVT)

- Infection

- Nerve damage

- Bone fracture (intraoperative or post-operative)

- Prosthesis-related complications: loosening or fracture of the prosthesis components, joint instability and dislocation, component misalignment and breakdown

- Stiffness

- Persistent/ chronic pain[49][50]

- Falls Risk

- DVT is a common complication after knee or hip replacement surgery that can cause significant morbidity and mortality. Incidence of DVT after knee or hip replacement has been reported at 18%, [51] and larger studies have reported that a hypercoagulable diagnosis puts patients at greater risk of a DVT within 6 months of joint replacement surgery. [52]

- Stiffness is the most common complaint following primary TKA, affecting approximately 6 to 7% of patients undergoing surgery. [36] Contemporary literature supports defining “acquired idiopathic stiffness” as having a range of motion of <90° persisting for >12 weeks after primary TKA, in the absence of complicating factors including pre-existing stiffness. Stiffness causes significant functional disability and lower satisfaction. [53]Females and obese patients are reported to be at increased risk[54].

- Evidence does not recommend routine use of continuous passive motion (CPM) as long term clinical and functional effects are insignificant[55][56] and not superior to traditional mobilisation techniques.[57]

- While more research is needed for the long term failure rates of TKA implants, available arthroplasty registry data shows that 82% of TKA surgeries and 70% of unilateral knee replacement surgeries last 25 years in patients with osteoarthritis. Polyethylene wear is a common cause for revision surgery. [1]

High-risk activities that may not be permitted, or require clearance with the orthopaedic surgeon, post-TKA surgery:

- Singles tennis, squash/racquet ball

- Jogging

- High impact aerobics

- Mountain biking

- Soccer, football, volleyball, baseball/softball, handball, volleyball, basketball

- Gymnastics

- Water-skiing/ water sports

- Skiing

- Skating

References[edit | edit source]

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 Evans JT, Walker RW, Evans JP, Blom AW, Sayers A, Whitehouse MR. How long does a knee replacement last? A systematic review and meta-analysis of case series and national registry reports with more than 15 years of follow-up. The Lancet. 2019 Feb 16;393(10172):655-63.

- ↑ Palmer, S., 2020. Total Knee Arthroplasty (TKA). [online] Medscape. Available at: <https://emedicine.medscape.com/article/1250275-overview#:~:text=The%20primary%20indication%20for%20total,pain%20caused%20by%20severe%20arthritis.> [Accessed 22 December 2020].

- ↑ Jakobsen TL, Jakobsen MD, Andersen LL, Husted H, Kehlet H, Bandholm T. Quadriceps muscle activity during commonly used strength training exercises shortly after total knee arthroplasty: implications for home-based exercise-selection. Journal of experimental orthopaedics. 2019 Dec 1;6(1):29.

- ↑ Scott CE, Oliver WM, MacDonald D, Wade FA, Moran M, Breusch SJ. Predicting dissatisfaction following total knee arthroplasty in patients under 55 years of age. The bone & joint journal. 2016 Dec;98(12):1625-34.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 Medscape. Total knee arthroplasty (TKA). Available from: https://emedicine.medscape.com/article/1250275-overview#:~:text=The%20primary%20indication%20for%20total,pain%20caused%20by%20severe%20arthritis. (accessed 28/07/2020).

- ↑ Maney AJ, Koh CK, Frampton CM, Young SW. Usually, selectively, or rarely resurfacing the patella during primary total knee arthroplasty: determining the best strategy. JBJS. 2019 Mar 6;101(5):412-20.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 Nucleus Medicine Media. Total Knee replacement surgery. Available from: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=EV6a995pyYk [Accessed 22 December 2020]

- ↑ Berstock JR, Murray JR, Whitehouse MR, Blom AW, Beswick AD. Medial subvastus versus the medial parapatellar approach for total knee replacement: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. EFORT open reviews. 2018 Mar;3(3):78-84.

- ↑ Parcells BW, Tria AJ. The cruciate ligaments in total knee arthroplasty. American Journal of Orthopaedics (Belle Mead NJ), 45(4), pp. E153-60. 2016;45(4):153-60.

- ↑ Physiopedia. 2020. Partial Knee Replacement. [online] Available at: <https://physio-pedia.com/Partial_Knee_Replacement?utm_source=physiopedia&utm_medium=search&utm_campaign=ongoing_internal> [Accessed 22 December 2020].

- ↑ 2020. Guideline - Joint Replacement (Primary): Hip, Knee And Shoulder. [ebook] NATIONAL INSTITUTE FOR HEALTH AND CARE 2 EXCELLENCE, p.5. Available at: <https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng157/documents/draft-guideline> [Accessed 22 December 2020].

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 Fan Y, Jin J, Sun Z, Li W, Lin J, Weng X, Qiu G. The limited use of a tourniquet during total knee arthroplasty: a randomized controlled trial. Knee. 2014; 21(6): 1263-1268

- ↑ Panjwani TR, Mullaji A, Doshi K, Thakur H. Comparison of functional outcomes of computer-assisted vs conventional total knee arthroplasty: a systematic review and meta-analysis of high-quality, prospective studies. The Journal of arthroplasty. 2019 Mar 1;34(3):586-93.

- ↑ Kloiber J, Goldenitsch E, Ritschl P. Patellar bone deficiency in revision total knee arthroplasty. Der Orthopade 2016;45(5):433.

- ↑ Skou ST, Graven‐Nielsen T, Rasmussen S, Simonsen OH, Laursen MB, Arendt‐Nielsen L. Facilitation of pain sensitization in knee osteoarthritis and persistent post‐operative pain: A cross‐sectional study. European Journal of Pain 2014;18(7):1024-31.

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 Blagojevic M, Jinks C, Jeffery A, Jordan 1. Risk factors for onset of osteoarthritis of the knee in older adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Osteoarthritis and cartilage 2010;18(1):24-33.

- ↑ 17.0 17.1 17.2 National Joint Registry, 2018. 15Th Annual Report 2018. National Joint Registry for England, Wales, Northern Ireland and the Isle of Man. [online] United Kingdom: National Joint Registry, pp.102-150. Available at: <https://www.hqip.org.uk/resource/national-joint-registry-15th-annual-report-2018/#.X-mMNxZS_Dc>[Accessed 22 December 2020].

- ↑ Knee Replacement Surgery By The Numbers - The Center [Internet]. The Center Orthopedic and Neurosurgical Care & Research. 2020 [cited 22 December 2020]. Available from: https://www.thecenteroregon.com/medical-blog/knee-replacement-surgery-by-the-numbers/https://www.thecenteroregon.com/medical-blog/knee-replacement-surgery-by-the-numbers/

- ↑ Singh JA, Yu S, Chen L, Cleveland JD. Rates of total joint replacement in the United States: future projections to 2020–2040 using the National Inpatient Sample. The Journal of rheumatology. 2019 Sep 1;46(9):1134-40.

- ↑ Ravi B, Croxford R, Reichmann WM, Losina E, Katz JN, Hawker GA. The changing demographics of total joint arthroplasty recipients in the United States and Ontario from 2001 to 2007. Best practice & research Clinical rheumatology. 2012 Oct 1;26(5):637-47.

- ↑ 21.0 21.1 American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons. TKR surgery by the numbers. Available from: https://www.anationinmotion.org/value/total-knee-replacement-surgery-numbers/ (last accessed 03/03/2019).

- ↑ Ravi B, Croxford R, Reichmann WM, Losina E, Katz JN, Hawker GA. The changing demographics of total joint arthroplasty recipients in the United States and Ontario from 2001 to 2007. Best practice & research Clinical rheumatology 2012;26(5):637-47.

- ↑ 23.0 23.1 Della Valle AG, Leali A, Haas S. Etiology and surgical interventions for stiff total knee replacements. HSS Journal 2007;3(2):182-9.

- ↑ 24.0 24.1 Foran J. Total Knee Replacement - OrthoInfo - AAOS [Internet]. Orthoinfo. 2020 [cited 22 December 2020]. Available from: https://orthoinfo.aaos.org/en/treatment/total-knee-replacement/

- ↑ Lee QJ, Mak WP, Wong YC. Risk factors for periprosthetic joint infection in total knee arthroplasty. Journal of Orthopaedic Surgery 2015;23(3):282-6.

- ↑ Polat G, Ceylan HH, Sayar S, Kucukdurmaz F, Erdil M, Tuncay I. Effect of body mass index on functional outcomes following arthroplasty procedures. World journal of orthopedics 2015;6(11):991.

- ↑ Jakobsen TL, Kehlet H, Husted H, Petersen J, Bandholm T. Early progressive strength training to enhance recovery after fast‐track total knee arthroplasty: a randomized controlled trial. Arthritis care & research 2014;66(12):1856-66.

- ↑ 28.0 28.1 28.2 Huber EO, de Bie RA, Roos EM, Bischoff-Ferrari HA. Effect of pre-operative neuromuscular training on functional outcome after total knee replacement: a randomized-controlled trial. BMC musculoskeletal disorders 2013;14(1):1-8.

- ↑ Husted RS, Juhl C, Troelsen A, Thorborg K, Kallemose T, Rathleff MS, Bandholm T. The relationship between prescribed pre-operative knee-extensor exercise dosage and effect on knee-extensor strength prior to and following total knee arthroplasty: a systematic review and meta-regression analysis of randomized controlled trials. Osteoarthritis and Cartilage. 2020 Sep 2.

- ↑ Kwok IH, Paton B, Haddad FS. Does pre-operative physiotherapy improve outcomes in primary total knee arthroplasty?—a systematic review. The Journal of arthroplasty 2015;30(9):1657-63.

- ↑ Alghadir A, Iqbal ZA, Anwer S. Comparison of the effect of pre-and post-operative physical therapy versus post-operative physical therapy alone on pain and recovery of function after total knee arthroplasty. Journal of physical therapy science. 2016;28(10):2754-8.

- ↑ Chesham R, Shanmugam S. Does preoperative physiotherapy improve postoperative, patient-based outcomes in older adults who have undergone total knee arthroplasty? A systematic review. Physiotherapy Theory and Practice. 2016;33(1):9-30.

- ↑ 33.0 33.1 Henderson KG, Wallis JA, Snowdon DA. Active physiotherapy interventions following total knee arthroplasty in the hospital and inpatient rehabilitation settings: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Physiotherapy 2018;104(1):25-35.

- ↑ Trzeciak T, Richter M, Ruszkowski K. Effectiveness of continuous passive motion after total knee replacement. Chirurgia narzadow ruchu i ortopedia polska 2011;76(6):345-9.

- ↑ 35.0 35.1 Husby VS, Foss OA, Husby OS, Winther SB. Randomized controlled trial of maximal strength training vs. standard rehabilitation following total knee arthroplasty. European journal of physical and rehabilitation medicine 2018;54(3):371-9.

- ↑ 36.0 36.1 Schache MB, McClelland JA, Webster KE. Lower limb strength following total knee arthroplasty: a systematic review. The Knee 2014;21(1):12-20.

- ↑ Adie S, Kwan A, Naylor JM, Harris IA, Mittal R. Cryotherapy following total knee replacement. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2012(9).

- ↑ 38.0 38.1 38.2 38.3 McHugh, A, Rehabilitation Guidelines Following Total Knee Arthroplasty. Physioplus. 2021.

- ↑ 39.0 39.1 39.2 39.3 Artz N, Elvers KT, Lowe CM, Sackley C, Jepson P, Beswick AD. Effectiveness of physiotherapy exercise following total knee replacement: systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC musculoskeletal disorders 2015;16(1):15.

- ↑ Jiang Y, Sanchez-Santos MT, Judge AD, Murray DW, Arden NK. Predictors of patient-reported pain and functional outcomes over 10 years after primary total knee arthroplasty: a prospective cohort study. The Journal of arthroplasty. 2017 Jan 1;32(1):92-100.

- ↑ 41.0 41.1 Bourne RB. Measuring tools for functional outcomes in total knee arthroplasty. Clinical orthopaedics and related research. 2008 Nov 1;466(11):2634-8.

- ↑ Meier W, Mizner R, Marcus R, Dibble L, Peters C, Lastayo PC. Total knee arthroplasty: muscle impairments, functional limitations, and recommended rehabilitation approaches. journal of orthopaedic & sports physical therapy. 2008 May;38(5):246-56.

- ↑ 43.0 43.1 43.2 43.3 Si HB, Zeng Y, Zhong J, Zhou ZK, Lu YR, Cheng JQ, Ning N, Shen B. The effect of primary total knee arthroplasty on the incidence of falls and balance-related functions in patients with osteoarthritis. Scientific reports. 2017 Nov 29;7(1):1-9.

- ↑ Thacoor A, Sandiford NA. Cryotherapy following total knee arthroplasty: What is the evidence?. Journal of Orthopaedic Surgery. 2019 Mar 1;27(1):2309499019832752.

- ↑ UnityPoint Health. Knee replacement exercise video. Available from:https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=nM0K5MlQc3U (last accessed 3.3.2019)

- ↑ 46.0 46.1 46.2 Moutzouri M, Gleeson N, Billis E, Tsepis E, Panoutsopoulou I, Gliatis J. The effect of total knee arthroplasty on patients’ balance and incidence of falls: a systematic review. Knee Surgery, Sports Traumatology, Arthroscopy. 2017 Nov 1;25(11):3439-51.

- ↑ 47.0 47.1 Chan AC, Jehu DA, Pang MY. Falls after total knee arthroplasty: frequency, circumstances, and associated factors—a prospective cohort study. Physical therapy. 2018 Sep 1;98(9):767-78.

- ↑ Arnold J, Walters J, Ferrar K. Does Physical Activity Increase After Total Hip or Knee Arthroplasty for Osteoarthritis? A Systematic Review. Journal of Orthopaedic & Sports Physical Therapy. 2016;46(6):431-442.

- ↑ Hasegawa M, Tone S, Naito Y, Wakabayashi H, Sudo A. Prevalence of Persistent Pain after Total Knee Arthroplasty and the Impact of Neuropathic Pain. The Journal of Knee Surgery. 2018;32(10):1020-1023.

- ↑ Kim M, Koh I, Sohn S, Kang B, Kwak D, In Y. Central Sensitization Is a Risk Factor for Persistent Postoperative Pain and Dissatisfaction in Patients Undergoing Revision Total Knee Arthroplasty. The Journal of Arthroplasty. 2019;34(8):1740-1748.

- ↑ Zhang H, Mao P, Wang C, Chen D, Xu Z, Shi D et al. Incidence and risk factors of deep vein thrombosis (DVT) after total hip or knee arthroplasty. Blood Coagulation & Fibrinolysis. 2016;28(2):126-133(8).

- ↑ Bawa H, Weick J, Dirschl D, Luu H. Trends in Deep Vein Thrombosis Prophylaxis and Deep Vein Thrombosis Rates After Total Hip and Knee Arthroplasty. Journal of the American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons. 2018;26(19):698-705.

- ↑ Clement N, Bardgett M, Weir D, Holland J, Deehan D. Increased symptoms of stiffness 1 year after total knee arthroplasty are associated with a worse functional outcome and lower rate of patient satisfaction. Knee Surgery, Sports Traumatology, Arthroscopy. 2018;27(4):1196-1203.

- ↑ Tibbo M, Limberg A, Salib C, Ahmed A, van Wijnen A, Berry D et al. Acquired Idiopathic Stiffness After Total Knee Arthroplasty. The Journal of Bone and Joint Surgery. 2019;101(14):1320-1330.

- ↑ Wirries N, Ezechieli M, Stimpel K, Skutek M. Impact of continuous passive motion on rehabilitation following total knee arthroplasty. Physiotherapy Research International. 2020;25(4).

- ↑ Mayer M, Naylor J, Harris I, Badge H, Adie S, Mills K et al. Evidence base and practice variation in acute care processes for knee and hip arthroplasty surgeries. PLOS ONE. 2017;12(7):e0180090.

- ↑ Trzeciak T, Richter M, Ruszkowski K. Efektywność ciagłego biernego ruchu po zabiegu pierwotnej endoprotezoplastyki stawu kolanowego [Effectiveness of continuous passive motion after total knee replacement]. Chirurgia Narzadów Ruchu i Ortopedia Polska. 2011;76(6):345-9.