Sacroiliac Joint: Difference between revisions

Kim Jackson (talk | contribs) No edit summary |

No edit summary |

||

| Line 5: | Line 5: | ||

</div> | </div> | ||

== Description == | == Description == | ||

[[File:Sacroiliac joint.png|right|frameless]] | |||

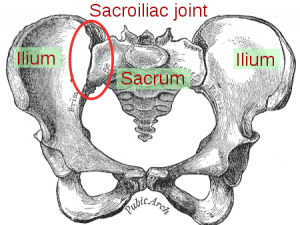

The | The Sacroiliac joint (simply called the SI joint) is the joint connection between the spine and the pelvis. | ||

* Large [[Joint Classification|diarthrodial join]]<nowiki/>t<ref name=":0">Cohen S., Steven P., Sacroiliac joint pain: a comprehensive review of anatomy, diagnosis and treatment, IARS, November 2005, volume 101, issue 5, pp 1440-1453 (LOE 3A)</ref> made up of the [[sacrum]] and the two innominates of the [[pelvis]]. | |||

The sacroiliac joints are essential for effective load transfer between the spine and the lower extremities. The sacrum, pelvis and spine-, are functionally interrelated through | * Each innominate is formed by the fusion of the three bones of the pelvis: the ilium, ischium, and pubic [[bone]].<ref name="Dutton">Dutton M. Orthopaedic Examination, Evaluation, and Intervention. 2nd ed. New York: McGraw Hill, 2008. </ref> | ||

* The sacroiliac joints are essential for [[Lumbosacral Biomechanics|effective load transfer]] between the spine and the lower extremities. | |||

* The sacrum, pelvis and spine-, are functionally interrelated through [[muscle]]<nowiki/>s, [[fascia]] and [[Ligament|ligamentous]] interconnections. | |||

== Motions Available == | == Motions Available == | ||

* The main function of the SI joint is to provide stability and attenuate forces to the lower extremities. | |||

* The strong ligamentous system of the joint makes it better designed for stability and limits the amount of motion available.<ref name="Cohen">Cohen SP. Sacroiliac Joint Pain: A Comprehensive Review of Anatomy, Diagnosis, and Treatment. ''Anesth Analg'' 2005; 101:1440-1453.</ref> | |||

* Nutation and Counternutation - movements that happen at the sacroiliac joint | |||

Nutation is the motion that occurs when force (weight) is absorbed at the sacroiliac joint, and occurs in the direction of gravitational forces (toward the ground). Counternutation is the body’s response, lifting the joint up against gravity.<ref>serola biomechanic [https://www.serola.net/nutation-counternutation-what-are-they-and-why-are-they-so-important/ Nutation] Available from:https://www.serola.net/nutation-counternutation-what-are-they-and-why-are-they-so-important/ (last accessed 12.6.2020)</ref> | |||

Nutation occurs | |||

* when the sacrum absorbs shock; it moves down, forward, and rotates to the opposite side. | |||

* as the sacrum moves anteriorly and inferiorly, the coccyx moves posteriorly relative to the ilium.<ref name="Levangie">Levangie PK, Norkin CC. Joint Structure and Function: A Comprehensive Analysis. 4th ed. Philadelphia: F.A. Davis, 2005.</ref> | |||

* This motion is opposed by the wedge shape of the sacrum, the ridges and depression of the articular surfaces, the friction coefficient of the joint surface, and the integrity of the posterior, interosseous, and sacrotuberous ligaments that are also supported by muscles that insert into the ligaments.<ref name="Dutton" /> | |||

<u>Counternutation</u> | <u>Counternutation</u> | ||

* the sacrum moves up, backward, and rotates to the same side that absorbs the force.<ref name="Levangie" /> This motion is opposed by the posterior sacroiliac ligament that is supported by the multifidus.<ref name="Dutton" /><br> | |||

== Ligaments & Joint Capsule | == Ligaments & Joint Capsule == | ||

'''Joint Capsule''' | '''Joint Capsule''' | ||

| Line 24: | Line 31: | ||

The sacroiliac joint capsule articular surfaces are made up of two strong layers which are C-shaped. The capsular portion on the ilium consists of a fibrocartilage while the capsular portion on the sacrum is made up of a hyaline cartilage, providing internal stability.<ref>A. Vleeming;M. D. Schuenke;A. T. Masi;J. E. Carreiro;L. Danneels and F. H. Willard. The sacroiliac joint: an overview of its anatomy, function and potential clinical implications; Journal of Anatomy Volume 221, Issue 6, pages 537–567, December 2012. (LOE 3A)</ref> The capsule attaches to both articular margins of the joint and becomes thicker as it moves inferiorly (sacral cartilage thicker than iliac cartilage).<br> | The sacroiliac joint capsule articular surfaces are made up of two strong layers which are C-shaped. The capsular portion on the ilium consists of a fibrocartilage while the capsular portion on the sacrum is made up of a hyaline cartilage, providing internal stability.<ref>A. Vleeming;M. D. Schuenke;A. T. Masi;J. E. Carreiro;L. Danneels and F. H. Willard. The sacroiliac joint: an overview of its anatomy, function and potential clinical implications; Journal of Anatomy Volume 221, Issue 6, pages 537–567, December 2012. (LOE 3A)</ref> The capsule attaches to both articular margins of the joint and becomes thicker as it moves inferiorly (sacral cartilage thicker than iliac cartilage).<br> | ||

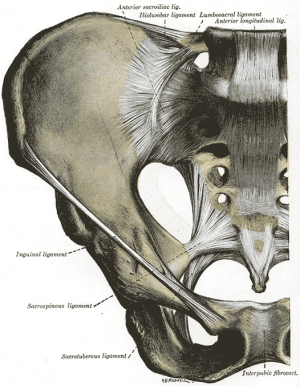

'''Ligaments: ''' | '''Ligaments: '''[[Image:Gray319.png|Anterior view of the ligaments of the sacroiliac joint|right|frameless]]The [[Pelvic Floor Anatomy|ligaments]] stabilizing the SI joint are the strongest ligaments in the body. They consist of: | ||

The [[Pelvic Floor Anatomy|ligaments]] stabilizing the SI joint are the strongest ligaments in the body. They consist of: | |||

*<u>Anterior Sacroiliac</u> - an anteroinferior thickening of the fibrous capsule that is weak and thin when compared to the other ligaments of the joint. It connects the third sacral ligament to the lateral side of the preauricular sulcus and is better developed closer to the arcuate line and the PSIS. This ligament is injured most often and is a common source of pain because of its thinness.<br> | *<u>Anterior Sacroiliac</u> - an anteroinferior thickening of the fibrous capsule that is weak and thin when compared to the other ligaments of the joint. It connects the third sacral ligament to the lateral side of the preauricular sulcus and is better developed closer to the arcuate line and the PSIS. This ligament is injured most often and is a common source of pain because of its thinness.<br> | ||

*<u>Interosseus Sacroiliac </u>- forms the major connection between the sacrum and the innominate and is a strong, short ligament deep to the posterior sacroiliac ligament. It resists anterior and inferior movement of the sacrum.<br> | *<u>Interosseus Sacroiliac </u>- forms the major connection between the sacrum and the innominate and is a strong, short ligament deep to the posterior sacroiliac ligament. It resists anterior and inferior movement of the sacrum.<br> | ||

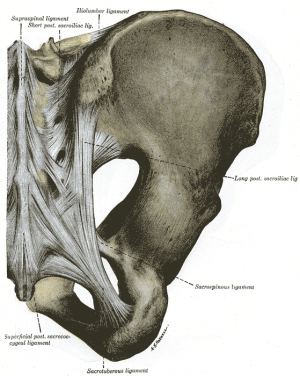

*<u>Posterior (Dorsal) Sacroiliac</u> - connects the PSIS with the lateral crest of the third and fourth segments of the sacrum and is very stong and tough. Nutation, which is anterior motion of the sacrum, slackens the ligament, and counternutation, which is posterior motion will make the ligament taut. It can be palpated directly below the PSIS and can often be a source of pain.<ref>Vleeming A, Pool-Goudzwaard AL, Hammudoghlu D, Stoeckart R, Snijders CJ, Mens JM. The function of the long dorsal sacroiliac ligament: its implication for understanding low back pain. Spine 1996;21:556-62 (LOE 3A)</ref><br> | *[[Image:Gray320.png|Posterior view of the ligaments of the sacroiliac joint|right|frameless]]<u>Posterior (Dorsal) Sacroiliac</u> - connects the PSIS with the lateral crest of the third and fourth segments of the sacrum and is very stong and tough. Nutation, which is anterior motion of the sacrum, slackens the ligament, and counternutation, which is posterior motion will make the ligament taut. It can be palpated directly below the PSIS and can often be a source of pain.<ref>Vleeming A, Pool-Goudzwaard AL, Hammudoghlu D, Stoeckart R, Snijders CJ, Mens JM. The function of the long dorsal sacroiliac ligament: its implication for understanding low back pain. Spine 1996;21:556-62 (LOE 3A)</ref><br> | ||

*<u>Sacrotuberous</u> - consists of three large fibrous bands and is blended with the posterior (dorsal) sacroiliac ligament. It stabilizes against nutation of the sacrum and counteracts against posterior and superior migration of the sacrum during weight bearing.<br> | *<u>Sacrotuberous</u> - consists of three large fibrous bands and is blended with the posterior (dorsal) sacroiliac ligament. It stabilizes against nutation of the sacrum and counteracts against posterior and superior migration of the sacrum during weight bearing.<br> | ||

*<u>Sacrospinous</u> - triangular shaped and thinner than the sacrotuberous ligament and goes from the ischial spine to the lateral parts of the sacrum and coccyx and then to the ischial spine laterally. Along with the sacrotuberous ligament, it opposes forward tilting of the sacrum on the innominates during weight bearing. | *<u>Sacrospinous</u> - triangular shaped and thinner than the sacrotuberous ligament and goes from the ischial spine to the lateral parts of the sacrum and coccyx and then to the ischial spine laterally. Along with the sacrotuberous ligament, it opposes forward tilting of the sacrum on the innominates during weight bearing.<ref name="Dutton" /><ref name="Levangie" /> <br> | ||

== Muscles == | == Muscles == | ||

| Line 124: | Line 129: | ||

== Other Important Information == | == Other Important Information == | ||

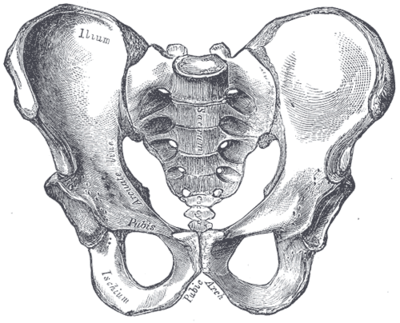

[[Image:Gray241.png|right|Sacroiliac joint|frameless|400x400px]]The SI joint goes through many changes throughout life. In early childhood, the surfaces of the joint are smooth and allow gliding motions in many directions.<ref name="Levangie" /> After puberty, the surface of the ilium becomes rougher and coated with fibrous plaques that will restrict motion significantly. These age-related changes will increase in the third and fourth decade and by the sixth decade motion may become noticeably restricted. By the eighth decade, plaque will form and erosions will be present.<ref name="Cohen" /> <br> | |||

The SI joint goes through many changes throughout life. In early childhood, the surfaces of the joint are smooth and allow gliding motions in many directions.<ref name="Levangie" /> After puberty, the surface of the ilium becomes rougher and coated with fibrous plaques that will restrict motion significantly. These age-related changes will increase in the third and fourth decade and by the sixth decade motion may become noticeably restricted. By the eighth decade, plaque will form and erosions will be present.<ref name="Cohen" /> <br> | |||

The ligaments of the SI ligament complex are weaker in women than in men, allowing the ability to give birth.<ref>Calvillo O., Skaribas I., Turnispeed J., Anatomy and pathophysiology of the SIJ, current science, 2000 (LOE 2A)</ref> | The ligaments of the SI ligament complex are weaker in women than in men, allowing the ability to give birth.<ref>Calvillo O., Skaribas I., Turnispeed J., Anatomy and pathophysiology of the SIJ, current science, 2000 (LOE 2A)</ref> | ||

Revision as of 07:25, 12 June 2020

Original Editors - Kathleen Nestor

Top Contributors - Kathleen Nestor, Admin, Lucinda hampton, Alexandra Kopelovich, Tony Lowe, Katie Sheidler, Kim Jackson, Tyler Shultz, Scott Buxton, Rachael Lowe, Laura Ritchie, Evan Thomas, WikiSysop, Abbey Wright, 127.0.0.1, Jenna Nodding and Yvonne Yap

Description[edit | edit source]

The Sacroiliac joint (simply called the SI joint) is the joint connection between the spine and the pelvis.

- Large diarthrodial joint[1] made up of the sacrum and the two innominates of the pelvis.

- Each innominate is formed by the fusion of the three bones of the pelvis: the ilium, ischium, and pubic bone.[2]

- The sacroiliac joints are essential for effective load transfer between the spine and the lower extremities.

- The sacrum, pelvis and spine-, are functionally interrelated through muscles, fascia and ligamentous interconnections.

Motions Available [edit | edit source]

- The main function of the SI joint is to provide stability and attenuate forces to the lower extremities.

- The strong ligamentous system of the joint makes it better designed for stability and limits the amount of motion available.[3]

- Nutation and Counternutation - movements that happen at the sacroiliac joint

Nutation is the motion that occurs when force (weight) is absorbed at the sacroiliac joint, and occurs in the direction of gravitational forces (toward the ground). Counternutation is the body’s response, lifting the joint up against gravity.[4]

Nutation occurs

- when the sacrum absorbs shock; it moves down, forward, and rotates to the opposite side.

- as the sacrum moves anteriorly and inferiorly, the coccyx moves posteriorly relative to the ilium.[5]

- This motion is opposed by the wedge shape of the sacrum, the ridges and depression of the articular surfaces, the friction coefficient of the joint surface, and the integrity of the posterior, interosseous, and sacrotuberous ligaments that are also supported by muscles that insert into the ligaments.[2]

Counternutation

- the sacrum moves up, backward, and rotates to the same side that absorbs the force.[5] This motion is opposed by the posterior sacroiliac ligament that is supported by the multifidus.[2]

Ligaments & Joint Capsule[edit | edit source]

Joint Capsule

The sacroiliac joint capsule articular surfaces are made up of two strong layers which are C-shaped. The capsular portion on the ilium consists of a fibrocartilage while the capsular portion on the sacrum is made up of a hyaline cartilage, providing internal stability.[6] The capsule attaches to both articular margins of the joint and becomes thicker as it moves inferiorly (sacral cartilage thicker than iliac cartilage).

Ligaments:

The ligaments stabilizing the SI joint are the strongest ligaments in the body. They consist of:

- Anterior Sacroiliac - an anteroinferior thickening of the fibrous capsule that is weak and thin when compared to the other ligaments of the joint. It connects the third sacral ligament to the lateral side of the preauricular sulcus and is better developed closer to the arcuate line and the PSIS. This ligament is injured most often and is a common source of pain because of its thinness.

- Interosseus Sacroiliac - forms the major connection between the sacrum and the innominate and is a strong, short ligament deep to the posterior sacroiliac ligament. It resists anterior and inferior movement of the sacrum.

- Posterior (Dorsal) Sacroiliac - connects the PSIS with the lateral crest of the third and fourth segments of the sacrum and is very stong and tough. Nutation, which is anterior motion of the sacrum, slackens the ligament, and counternutation, which is posterior motion will make the ligament taut. It can be palpated directly below the PSIS and can often be a source of pain.[7]

- Sacrotuberous - consists of three large fibrous bands and is blended with the posterior (dorsal) sacroiliac ligament. It stabilizes against nutation of the sacrum and counteracts against posterior and superior migration of the sacrum during weight bearing.

- Sacrospinous - triangular shaped and thinner than the sacrotuberous ligament and goes from the ischial spine to the lateral parts of the sacrum and coccyx and then to the ischial spine laterally. Along with the sacrotuberous ligament, it opposes forward tilting of the sacrum on the innominates during weight bearing.[2][5]

Muscles[edit | edit source]

There are 35 muscles that attach to the sacrum or innominates which mainly provide stability to the joint rather than producing movements.[8]

Muscles that attach to the sacrum or innominates:

- Adductor brevis

- Adductor longus

- Adductor magnus

- Biceps femoris - long head

- Coccygeus

- Erector spinae

- External oblique

- Gluteus maxiumus

- Gluteus medius

- Gluteus minimus

- Gracilis

- Iliacus

- Inferior gemellus

- Internal oblique

- Latissimus dorsi

- Levator ani

- Multifidus

- Obturator internus

- Obturator externus

- Pectineus

- Piriformis

- Psoas minor

- Pyramidalis

- Quadratus femoris

- Quadratus lumborum

- Rectus abdominis

- Rectus femoris

- Sartorius

- Semimembranosus

- Semitendonosus

- Sphincter urethrae

- Superficial transverse perineal ischiocavernous

- Superior gemellus

- Tensor fascia lata

- Transversus abdominus

Specific Pathologies[edit | edit source]

There are many pathologies that could present at the site of the sacroiliac joint including:[2]

- Sacroiliac tuberculosis

- Spondyloarthropathy

- Crystal and pyogenic arthropathies

- Groin pain

- Osteitis pubis

- Pubic symphysis dysfunction

- Osteoarthritis

- Stress fracture

Epidemiology[edit | edit source]

The reported prevalence of sacroiliac joint pain in cases of chronic low back and lower extremity pain is estimated to be between 10 - 27%[9]. There are several reported predisposing factors for SIJ pain such as a leg length discrepancy, age, arthritis, previous spine surgery, pregnancy and trauma. Compared with face and discogenic low back pain, SIJ pain is more likely to be reported as a specific inciting event, and present unilaterally below L5 and the pain patterns are extremely variable[3].

Special Tests[2][edit | edit source]

SI Joint Stress tests

- Anterior Gapping test

- Posterior Distraction test

- Pubic Stress test

- Sacrotuberous Ligament Stress test

- Sacral Compression test

- Rotational Stress test

Leg Length tests

- Prone test

- Standing leg length test

- Functional leg length test

Other Special Tests

- Seated Flexion test (Piedallu's Sign)

- Long Sit test

- Sign of the Buttock

- Posterior Pelvic Pain Provocation test

- Gaenslen's test

- Yeoman's test

- FABER (Figure-Four) test

- Fortin Finger Test

- Stright Leg Raise - 70-90deg[10]

- Gillet's test (Ipsilateral posterior rotation test)[11]

Other Important Information[edit | edit source]

The SI joint goes through many changes throughout life. In early childhood, the surfaces of the joint are smooth and allow gliding motions in many directions.[5] After puberty, the surface of the ilium becomes rougher and coated with fibrous plaques that will restrict motion significantly. These age-related changes will increase in the third and fourth decade and by the sixth decade motion may become noticeably restricted. By the eighth decade, plaque will form and erosions will be present.[3]

The ligaments of the SI ligament complex are weaker in women than in men, allowing the ability to give birth.[12]

Related Pages[edit | edit source]

Resources[edit | edit source]

Wheeless' Textbook of Orthopaedics

References[edit | edit source]

- ↑ Cohen S., Steven P., Sacroiliac joint pain: a comprehensive review of anatomy, diagnosis and treatment, IARS, November 2005, volume 101, issue 5, pp 1440-1453 (LOE 3A)

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 2.4 2.5 Dutton M. Orthopaedic Examination, Evaluation, and Intervention. 2nd ed. New York: McGraw Hill, 2008.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 Cohen SP. Sacroiliac Joint Pain: A Comprehensive Review of Anatomy, Diagnosis, and Treatment. Anesth Analg 2005; 101:1440-1453.

- ↑ serola biomechanic Nutation Available from:https://www.serola.net/nutation-counternutation-what-are-they-and-why-are-they-so-important/ (last accessed 12.6.2020)

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 5.3 Levangie PK, Norkin CC. Joint Structure and Function: A Comprehensive Analysis. 4th ed. Philadelphia: F.A. Davis, 2005.

- ↑ A. Vleeming;M. D. Schuenke;A. T. Masi;J. E. Carreiro;L. Danneels and F. H. Willard. The sacroiliac joint: an overview of its anatomy, function and potential clinical implications; Journal of Anatomy Volume 221, Issue 6, pages 537–567, December 2012. (LOE 3A)

- ↑ Vleeming A, Pool-Goudzwaard AL, Hammudoghlu D, Stoeckart R, Snijders CJ, Mens JM. The function of the long dorsal sacroiliac ligament: its implication for understanding low back pain. Spine 1996;21:556-62 (LOE 3A)

- ↑ Calvillo O., Skaribas I., Turnispeed J., Anatomy and pathophysiology of the SIJ, current science, 2000 (LOE 2A)

- ↑ Simopoulos T. Manchikanti L. Singh V. Gupta S. Hameed H. Diwan S. Cohen P. A Systematic valuation of Prevalence and Diagnostic Accuracy of Sacroiliac Joint Interventions. Pain Physician 2012; 15:E305-E344 (http://www.painphysicianjournal.com/2012/may/2012;15;E305-E344.pdf)

- ↑ Magee, DJ. Orthopedic Physical Assessment. 5th ed. St Louis:Saunders, an imprint of Elsevier INC, 2008.

- ↑ Magee, DJ. Orthopedic Physical Assessment. 5th ed. St Louis:Saunders, an imprint of Elsevier INC, 2008.

- ↑ Calvillo O., Skaribas I., Turnispeed J., Anatomy and pathophysiology of the SIJ, current science, 2000 (LOE 2A)