Pubic Symphysis Dysfunction

Description[edit | edit source]

Pubic Symphysis Dysfunction has been described as a collection of signs and symptoms of discomfort and pain in the pelvic area, including pelvic pain radiating to the upper thighs and perineum.[1][2] These occur due to the physiological pelvic ligament relaxation and increased joint mobility seen in pregnancy. The severity of symptoms varies from mild discomfort to severely debilitating pain.

It has also been discussed using a multitude of terms in the literature including pubo-sacroiliac arthropathy, pelvic insufficiency, symphysis pain syndrome, pelvic joint syndrome, pelvic girdle pain, pelvic relaxation syndrome and most of all symphysis pubis dysfunction.[2]

Symphysis pubis dysfunction (SPD) occurs where the joint becomes sufficiently relaxed to allow instability in the pelvic girdle. In severe cases of SPD the symphysis pubis may partially or completely rupture. Where the gap increases to more than 10 mm this is known as diastasis of the symphysis pubis (DSP).[3]

“A symphysis pubis dysfunction is a common and debilitating condition affecting woman, as it mostly happens during/after pregnancy. It’s painful and it can have a significant impact on quality of life, which can lead to complications as depression."[3]

Clinically Relevant Anatomy[edit | edit source]

The Pubic Symphysis[edit | edit source]

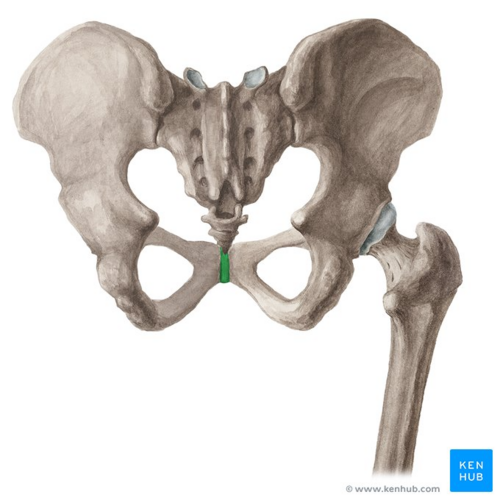

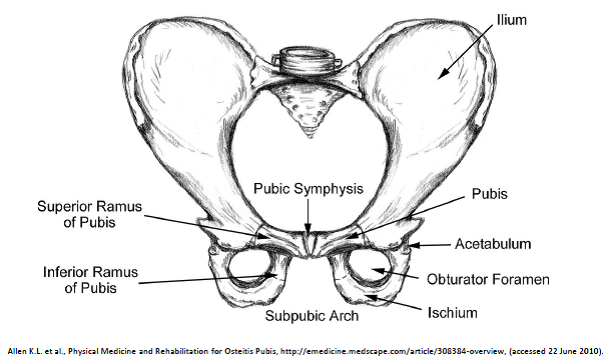

The pubic symphysis is found on the anterior side of the pelvis and is the anterior boundary of the perineum.[2][3] The pubic bones form a cartilaginous joint in the median plane, the symphysis pubis.[2] The joint keeps the two bones of the pelvis together and steady during activity.

In cooperation with the sacroiliac joints, the symphysis forms a stable pelvic ring. This ring allows only some small mobility.[4]

The pubic symphysis is a cartilaginous joint which consists of a fibrocartilaginous interpubic disc.[2][3]The pubic bones are connected by four ligaments. The superior pubic ligaments start on the superior part of the pubis and go as far as the pubic tubercles. The arcuate pubic ligaments form the lower border of the pubic symphysis and blends with the fibrocartilaginous disc.[2] The joint stability is mostly given by the arcuate ligament and is also the strongest one. The four ligaments together neutralise shear and tensile stresses.[3]

The disc connects the adjacent surfaces of the two pubic bones. Both of these surfaces contain a thin layer of hyaline cartilage.[2] The junction is not flat, there are papilliform elevations with reciprocal depressions and ridges.[3]

This disc is very small in children and the hyaline cartilage is very wide, but it evolves conversely. The disc is higher, smaller and narrower in men.[2][3] Normally with women is the symphysis pubic gap 4-5 mm wide and it widens 2-3 mm during the last trimester of pregnancy. This is necessary to facilitate the delivery of the baby.[3] With symphysis pubis dysfunction the joints become more relaxed and allow instability in the pelvic girdle. When the gap is equal to or more than 10 mm there’s a diastasis of the symphysis pubic.[3]

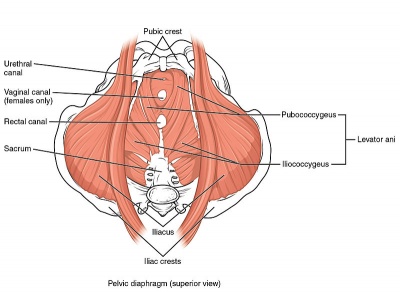

The Pelvic Floor[edit | edit source]

There are three layers of pelvic floor muscles. The first is the superficial perineal layer (innervated by the pudendal nerve) comprising the Bulbocavernosus, Ischiocavernosus, Superficial transverse perineal and external anal sphincter (EAS).

The second layer comprises the deep urogenital diaphragm layer (innervated by pudendal nerve) including the Compressor urethera, Uretrovaginal sphincter, Deep transverse perineal.

The third layer is the pelvic diaphragm (innervated by sacral nerve roots S3-S5) including Levator ani, pubococcygeus (pubovaginalis, puborectalis), iliococcygeus, coccygeus/ischiococcygeus], Piriformis, Obturator internus.

The pelvic floor muscles function as a support for the organs that lie on it. The sphincters (anal and urethral sphincters) provide conscious control over the bowels and bladder, respectively, such that we are able to control the release of faeces/flatus, or urine, and to prevent and delay emptying until convenient.

Upon contraction, pelvic floor muscles will lift upwards the internal organs, and tighten the sphincters openings of the vagina, anus and urethra. Relaxation of the pelvic floor muscles allows for passage of faeces and urine.

Pregnancy tends to change all these muscles and so also their function.

Aetiology[edit | edit source]

Some common causes:[3]

- Diastasis

- Rupture

- Osteomy

- Fracture

- Misalignment of the pelvis

- Frequently associated with pregnancy and childbirth

- Increased age when bearing a child

- Sports injury: caused by falling with the legs in hyper-abduction (example: horse-riding)

- Prostatectomy

Pregnancy[edit | edit source]

The exact cause of SPD is unknown certain but there are some theories.

Aslan et al.(2007) say that the aetiology of SPD is unknown.[2] Pregnancy leads to an altered pelvic load, lax ligaments and weaker musculature. This leads to spinopelvic instability, which manifests itself as symphysis pubic dysfunction.[3]

In the early stages of the pregnancy the corpus luteum secretes a lot of relaxin and progesterone.[3] From the 12th week of the pregnancy, this function is continued by the placenta and decidua.[3] Relaxin breaks down collagen in the pelvic joint and causes laity and softening. Progesterone has a similar effect. But relaxin has no correlation with the degree of symptoms of symphysis pubic dysfunction.[3] A Norwegian study showed that genetic susceptibility to joint dysfunction is possibly caused by an aberration of relaxin.[5] It would seem that the presence of laxity as the result of a hormonal link is undisputed.[3] However, there is no full disclosure for this.

Other factors contributing to SPD include physically strenuous work during pregnancy and fatigue with poor posture and lack of exercise. Weight gain, multiparity, increased maternal age and a history of difficult deliveries, including shoulder dystocia, may also play a role.

The effective accommodation of the joints to each specific load demand through an adequately tailored joint compression, as a function of gravity, coordinated muscle and ligament forces, to produce effective joint reaction forces under changing conditions, Because of the pregnancy (hormones) ligaments and muscles become more lax and no longer have the same ability than they had before, this is why pregnancy leads to an altered pelvic load. In combination, these lead to spinopelvic instability, most commonly manifest as SPD.[3]

In short, the causes for this instability include hormonal (relaxin), metabolic (calcium), biomechanical (load of pregnancy or physical exercise), weak musculature, body composition (weight), anatomical and genetic variations.[2]

Epidemiology[edit | edit source]

The prevalence of SPD has been reported as follows:[1][3][6]

- Increased level of cases of pubic symphysis dysfunction

- 75% of women developed SPD in the first trimester of pregnancy while 89% of women developed SPD in the second and third trimester

- According to Owens et al, injury arises in:[1][6]

- First trimester of pregnancy for 9% of women

- Second trimester of pregnancy for 44% of women

- Third trimester for 15% of women

- Postnatal 2% of women

- Incidence of 1:36 and 1:300 in British population[6]

- Occasionally SPD may occur in labour or in the puerperium (six weeks postpartum)

Clinical Presentation[edit | edit source]

Symphysis pubic dysfunction is a condition that causes excessive movement of the pubic symphysis in the anterior or lateral direction and causes pain.

Symptoms[edit | edit source]

Symptoms include[3]:

- Pain:

- Burning, shooting, grinding or stabbing

- Mild or prolonged

- Usually relieved by rest

- Radiating to the back, abdomen, groin, perineum and legs

- Disappears commonly after giving birth (not in every case)

- Discomfort sense onto the front of the joint

- Clicking of the lower back, hip joints and sacroiliac joints when changing position

- Difficulty in movements like abduction and adduction

- Locomotor difficulty:

- Walking

- Ascending or descending stairs

- Rising from a chair

- Weight-bearing activities

- Standing on one leg

- Turning in bed

- Depression, possibly due to the discomfort

Differential Diagnosis[edit | edit source]

The potential symptoms of the differential diagnosis of SPD need to be firmly excluded through clinical history, physical examination and appropriate investigations, to ensure the diagnosis of symphysis pubic dysfunction.

The symptoms which may lead to a diagnosis of SPD, are nerve compression (intervertebral disc lesion), symptomatic low back pain (lumbago and sciatica), pubic osteolysis, osteitis pubis, bone infection (osteomyelitis, tuberculosis, syphilis), urinary tract infection, round ligament pain, femoral vein thrombosis and obstetric complications.[2][3]

Diagnostic Procedures[edit | edit source]

As in all dysfunctions, an early diagnosis is important to minimize the possibility of a long term problem. However, not all healthcare practitioners recognise this problem.

Leadbetter et al.[7] described, according to their findings, a scoring system to diagnose symphysis pubic dysfunction based on pain during four activities and previous injury, which might be significant to determine symphysis pubic dysfunction. [2]

1. Pubic bone pain on walking

2. Standing on one leg

3. Climbing stairs

4. Turning over in bed

5. Previous damage to lumbosacral spine or pelvis

A diagnosis is often made symptomatically e.g. after pregnancy but imaging is the only way to confirm diastasis of the symphysis pubis.[3] Radiography, like an MRI (magnetic resonance imaging), x-ray, CT (computerised tomography) or ultrasound, has been used to confirm the separation of the symphysis pubis.[3] Although it is not considered as the method of choice because of the danger of exposing the fetus to ionizing radiation. A better technique with superior spatial resolution and avoidance of ionizing radiation is MRI.

Other techniques that may aid in diagnosis and monitoring the treatment of symphysis pelvic dysfunction, are transvaginal or transperineal ultrasonography, using high-resolution transducers.[2] Ultrasonography is a useful diagnostic aid which can measure the interpubic distance. This can be a consequence of diastasis of the pubic symphysis following childbirth.

The interpubic distance is usually measured with electronic callipers. It’s also important to know that ultrasonography provides a simple means of measuring interpubic gap, without exposure to ionizing radiation.[8]

Outcome Measures[edit | edit source]

SPD has been described as a collection of signs and symptoms of discomfort and pain in the pelvic area. Pain measures such as the Pain Disability Index and instability in the pelvic girdle are often used. Outcome measures such as the Roland-Morris Questionnaire and the Patient-Specific Functional Scale show significant improvement in function over time although there was no significant difference (P=.05) among groups (exercise versus pelvic support belts).[9]

Further research is needed to develop a scoring system for symphysis pubis dysfunction for a condition-specific measure.

http://www.physio-pedia.com/Roland‐Morris_Disability_Questionnaire

http://www.physio-pedia.com/Visual_Analogue_Scale

http://www.tbims.org/combi/drs/DRS%20Form.pdf

Examination[edit | edit source]

A physical examination is important for differentiating other possible causes, such as lumbar spine problems or prolapsed discs and to get a proper diagnosis.[2][3]

The most useful tests are:

- Palpation with the patient in supine of the entire anterior surface of the symphysis pubis elicits pain that stays for more than 5 seconds after the removal of the examiner’s hand. (99% specificity, 60% sensitivity and 0.89 Kappa coefficient) [3]

- When you let the patient stand on one leg, they are unable to maintain their pelvis in the horizontal plane cause the opposite buttock drops (The Trendelenburg’s sign: 99% specificity, 60% sensitivity and 0.63 Kappa coefficient)[3]

- Patrick’s faber sign, see ‘palpation’ (specificity 99%, 40% sensitivity and 0.54 Kappa coefficient)[3]

These tests for symphyseal pain in pregnancy have high specificity, sensitivity and inter-examiner reliability ( with a Kappa coefficient > 0.40). [3]

Palpation[edit | edit source]

Palpation of the following:[2]

- Tenderness of the symphysis pubis

- Tenderness of the sacroiliac joint

- The sacrotuberous ligament

- The tenderness of muscles including Gluteal muscles, M. iliopsoas, M. piriformis and para-vertebralis

Provocative Tests[edit | edit source]

When the following tests are positive, they are helpful in diagnosing SPD [2][10].

- Patrick’s Faber sign

- One iliac spine is fixed by the examiner, the patient lies in a supine position, the patient places the opposite heel on the ipsilateral knee with the leg falling passively outwards. The test is positive when there is pain in either sacroiliac joint

- Active straight leg raise (ASLR)

- Pain at symphysis when standing on one leg

- Bilateral trochanteric compression

Range of Motion[edit | edit source]

Range can be limited by pain[3], notably during lateral rotation and during abduction. In particular, a waddling gait[2][3] can result from impairment of the M. gluteus medius which loses its function as abductor.

Medical Management[edit | edit source]

During pregnancy:

- Paracetamol[3]

- Codeine-based preparations [3]

- Lumbar epidural morphine/bupivacaine/fentanyl usage for 24-72 hours, to break the vicious cycle of pain and muscle spasm[11]

After delivery:

- NSAIDS[3]

- Lumbar epidural morphine/bupivacaine/fentanyl usage for 24-72 hours, to break the vicious cycle of pain and muscle spasm[11]

Others:

- Hospital pain team, when intractable cases[3]

- Intra-symphyseal injection of a combination of hydrocortisone, chymotrypsin and lidocain[3]

It is important to closely monitor the effectiveness and side-effects of these interventions[3]

Physical Therapy Management[edit | edit source]

Devices[edit | edit source]

Aids to assist load-bearing:[3]

- Elbow crutches

- Pelvic support devices

- Lumbopelvic belt

- The belt must be positioned just cranial to the greater trochanters. The study advises not to use pelvic belts as a monotherapy because stability of the lumbopelvic area has to established by proper motor control and coordination.

- Prescribed pain reliefs (careful taking NSAID while pregnant)

- Wheelchair in very severe cases

- Social services

Birth-planning[edit | edit source]

Position during birth is important: [3]

- Women with PSD should give birth in an upright position, with knees slightly open

- the gap may never exceed the maximal comfort zone which is why it’s suggested that the patient wear a ribbon to both legs.[2][3]

- Practices such as placing the feet on the midwife's hips during birth, stirrups, and interventions such as forceps should be avoided in the delivery room if possible because they can strain ligaments further.[3]

- During labour and delivery leg abduction (=separation) should be kept to a minimum[3].

Prevention[edit | edit source]

Advice during pregnancy can help reduce fear and enable patients to become active in their own treatment:[12]

- Giving information about the condition and relationship between impairment, load demand, and actual loading capacity

- The importance of necessary rest

- Giving advice to use the body in daily life e.g. sit down while doing things if possible, sleep with a pillow between the legs and keep legs flexed and together to get in/ out of bed[3]

Back Care[edit | edit source]

- Avoid activities that put undue strain on the pelvis (squatting, strenuous exercises, prolonged standing, lifting and carrying, stepping over things, twisting movements of the body, vacuum cleaning and stretching exercises)[3][4]

- The lumbopelvic belt combined with information is superior to exercise and information or information alone. The women are allowed to remove the belt only during sleeping.[13]

Exercises[edit | edit source]

Various modes of exercise for the hip can help[3][4]:

- Aerobic exercises

- Brisk walking with a medium intensity

- Defined as 64 to 76% of maximum heart rate

- For 25 minutes per day and 3 days per week

- Stretching exercises:

- Hamstring, inner thigh, side waist, quadriceps and back stretch

- For two times per day and three times per week

- Duration of each occasion: 10 to 20 seconds

- Strengthening exercises:

- Forward bending, back pressing, diagonal curling, upper body bending, leg lift crawling along with kegel exercise and pelvic tilt was given to the patients.

- For 3 to 5 times per each exercise session for both sides of the body while performing 2 exercise bouts per day and 3 days per week

- Duration of each occasion: 3 to 10 seconds

- Pelvic muscle floor exercises (Exercises for Lumbar Instability)

- Early pregnancy: to reduce the risk to develop SPD

- Deep abdominal exercises: to increases the core stability and to prevent women to develop pelvic or back pain during pregnancy

- Can be progressed by starting off with a small number of repetitions and gradually increasing the seconds to hold on a contraction

- M. transversus abdominus is an important muscle when he contracts, we can see a synergistic activation of the pelvic floor

- Stabilisation/core stability exercises: [3][8]

- Aimed at improving motor control and stability through improving force closure of the pelvis

- Initially: contraction of the transverse abdominal wall muscles

- Specific training of the deep local muscles like the transverse abdominal wall muscles with co-activation of the lumbar multifidus in the lumbosacral region

- Training of the superficial global muscles

- Exercises to increase circulation in hip rotator muscles.[12]

- Many repetitions during low force in a limited range of motion

- Side-lying position with a pillow between the legs or sitting without foot support

Other Therapies[edit | edit source]

Although efficacy is not yet proven, other adjunct therapies include[3]:

Clinical Bottom Line[edit | edit source]

Pubic Symphysis Dysfunction has been described as a collection of signs and symptoms of discomfort and pain in the pelvic area, including pelvic pain radiating to the upper thighs and perineum. It can be examined by palpation, provocation tests, a wadding gait, also a continuous pain during activities can predict pubic symphysis dysfunction. Also, MRI can diagnose this condition. In the latest literature, we see that SPD is treated in a lot of ways. First, there is birth planning, in this aspect several criteria could help avoid this condition. Giving information about the condition itself may be used so that the patiënt knows what can be done and what is not. Exercise is also an important aspect, where aerobic, strengthening, pelvic muscle floor and stabilisation exercises are combined. Other therapies like acupuncture, TENS, ice, external heat and massage are also done but their efficacy has not yet been proven. During and after pregnancy a symptomatic treatment can be given, this is to limit the pain and is always with physical therapy.

References[edit | edit source]

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 Welsh A., Antenatal care routine care for the healthy pregnant woman, National Collaborating Centre for Women’s and Children’s Health, 2008, 2nd edition, London, 113

- ↑ 2.00 2.01 2.02 2.03 2.04 2.05 2.06 2.07 2.08 2.09 2.10 2.11 2.12 2.13 2.14 2.15 2.16 2.17 Aslan A. and Fynes M., Symphyseal pelvic dysfunction, Current Opinion Obstetrics and Gynecology, 2007 19:133–139.

- ↑ 3.00 3.01 3.02 3.03 3.04 3.05 3.06 3.07 3.08 3.09 3.10 3.11 3.12 3.13 3.14 3.15 3.16 3.17 3.18 3.19 3.20 3.21 3.22 3.23 3.24 3.25 3.26 3.27 3.28 3.29 3.30 3.31 3.32 3.33 3.34 3.35 3.36 3.37 3.38 3.39 3.40 3.41 3.42 3.43 Jain S, Eedarapalli P, Jamjute P, Sawdy R. Symphysis pubis dysfunction: a practical approach to management. The Obstetrician & Gynaecologist 2006;8:153–158.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 Kordi R. Et. Al. Comparison between the effect of lumbopelvic belt and home based pelvic stabilizing exercise on pregnant women with pelvic girdle pain; a randomized controlled trial. J Back Musculoskelet Rehabil. 2013;26(2):133-9

- ↑ MacLennan AH, MacLennan SC., Symptom-giving pelvic girdle relaxation of pregnancy, postnatal pelvic joint syndrome and development dysplasia of the hip., Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand, 1997;76:760–64.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 Owens K, Pearson A, Mason G. Symphysis pubis dysfunction - a cause of significant obstetric morbidity. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol 2002;105:143–46.

- ↑ Leadbetter, R. E., D. Mawer, and S. W. Lindow. "Symphysis pubis dysfunction: a review of the literature." The Journal of Maternal-Fetal & Neonatal Medicine 16.6 (2004): 349-354.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 M.W. Scriven MS FRCS, Dai Anthony Jones MChlr FRCS, Liam McKnight FRCR, “The importance of pubic pain following childbirth: a clinical and ultrasonographic study of diastasis of the pubic symphysis, J R Soc Med 1995;88:28-30.

- ↑ Depledge J. et al., Management of Symphysis Pubis Dysfunction During Pregnancy Using Exercise and Pelvic Support Belts, Physical Therapy,2005, 1290-1300

- ↑ Albert, H. Et Al. "Evaluation of clinical tests used in classification procedures in pregnancy-related pelvic joint pain." European Spine Journal 9.2 (2000): 161-166)

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 Scicluna JK, Alderson JD, Webster VJ, Whiting P. Epidural analgesia for acute symphysis pubis dysfunction in the second trimester. Int J Obstet Anesth 2004;13:50–2.

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 Elden H, Ladfors L, Olsen MF, Ostgaard HC, Hagberg H., Effects of acupuncture and stabilising exercises as adjunct to standard treatment in pregnant women with pelvic girdle pain: randomised single blind controlled trial, BMJ ,2005;330:761

- ↑ Stuge B, Msc, et al., The Efficacy of a Treatment Program Focusing on Specific Stabilizing Exercises for Pelvic Girdle Pain After Pregnancy, SPINE Volume 29, Number 10, pp E197–E203 2004