Pregnancy Related Pelvic Pain

Original Editors - Marlies Verbruggen

Top Contributors - Marlies Verbruggen, Nicole Hills, Rotimi Alao, Andeela Hafeez, Lara Lagrange, Vanwymeersch Celine, Admin, Kim Jackson, Laura Ritchie, Rachael Lowe, Simisola Ajeyalemi, WikiSysop, Wanda van Niekerk, Evan Thomas and Fasuba Ayobami

Introduction[edit | edit source]

According to the European guidelines created by Vleeming and colleagues,[1] “Pelvic girdle pain (PGP) generally arises in relation to pregnancy, trauma, arthritis and osteoarthritis. Pain is experienced between the posterior iliac crest and the gluteal fold, particularly in the vicinity of the sacroiliac joints (SIJ). The pain may radiate in the posterior thigh and can also occur in conjunction with/or separately in the symphysis. The endurance capacity for standing, walking, and sitting is diminished. The diagnosis of PGP can be reached after exclusion of lumbar causes. The pain or functional disturbances in relation to PGP must be reproducible by specific clinical tests”[1]

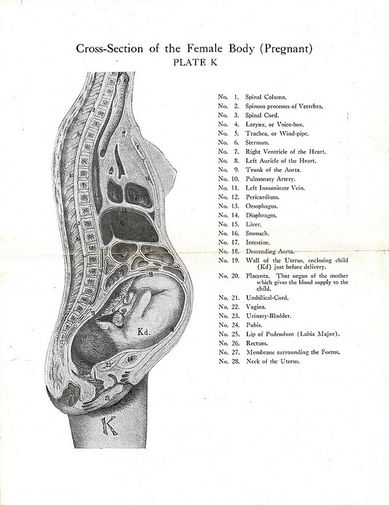

Clinically Relevant Anatomy[edit | edit source]

The pelvis is composed of the sacrum, ilium, ischium and pubis. The pelvic bone consists the pubic symphysis and the sacroiliac joint.

Sacroiliac Joints

The sacroiliac joints allow for the transfer of forces between the spine and the lower extremity.[2] To read more about the function of the sacroiliac joints review: Force and Form Closure

Pelvic Floor

The pelvic floor muscles have two primary functions in females. The muscles:[3]

- support the abdominal viscera (bladder, intestines, uterus) and the rectum

- control the mechanism for continence for the urethral, anal and vaginal orifices[3]

Etiology[edit | edit source]

The etiology of pregnancy-related pelvic girdle pain has not been clearly established in the literature.[4] However, the cause of this pain is believed to be multi-factorial and may be related to hormonal, biomechanical, traumatic, metabolic, genetic and degenerative factors.[5] [6] [7]

Hormonal[edit | edit source]

Women produce increased quantities of the hormone relaxin during their pregnancy. Relaxin increases ligament laxity in the pelvic girdle (and in other parts of the body) in preparation for the labour process. Increased ligament laxity may cause a small increase in the range of motion at the pelvis. If this increase in motion is not complimented by a change in neuromotor control (e.g., muscles around the pelvis act to improve stability), it is possible that pain may occur.[1] However, the link between relaxin and pelvic girdle pain during pregnancy has not been established in the literature.[6][7] Research to date also does not support the idea that an increase in the range of motion at the pelvis causes pain.[1][8] [9]

Biomechanical[edit | edit source]

As pregnancy progresses, the gravid uterus increases load on the spine and pelvis. To accommodate for the growth of the uterus the pubic symphysis must soften and laxity in the pelvic ligaments increases. The uterus shifts forward which changes the maternal centre of gravity and the orientation of pelvis.[10] This change in centre of gravity may cause stress or a change in load on the lower back and pelvic girdle.[6][11][7] This change in load can result in compensatory postural changes (e.g., an increase in lumbar lordosis).[6][11][7]

Risk Factors[edit | edit source]

The risk factors for developing pregnancy-related pelvic girdle pain are:

- a previous history of low back pain or pelvic girdle pain.[12][7]

- a previous trauma to the pelvis or back.[12][7]

- physical demanding work (e.g., twisting and bending the back several times per hour per day).[1][13][14][15][16]

- multiparity - may play a causal role in the development of pregnancy-related pelvic girdle pain[17]

Epidemiology[edit | edit source]

Pelvic girdle pain may begin around the 18th week of pregnancy and appears to peak between the 24th and 36th week.[18] Pelvic pain affects approximately 50% of women during pregnancy.[13] 25% of the women who experience pelvic girdle pain report having severe pain and 8% report pain that causes severe disability.[19]

Clinical Presentation[edit | edit source]

The clinical presentation of pregnancy-related pelvic girdle pain can vary from patient to patient and can change over the course of the patient's pregnancy.[13] Since the causes of pregnancy-related pelvic girdle pain are multi-factorial and, it is important to incorporate a biopsychosocial approach to the diagnosis and treatment of this pain.

Subjective History[edit | edit source]

Common symptoms related to pregnancy-related pelvic pain include:

- a difficulty walking quickly and covering long distances[1][20][13]

- pain/discomfort/difficulty during sexual intercourse[20][13]

- pain/discomfort during sleep and/or a difficulty turning over in bed[13][21]

- decreased ability to perform housework[13][21]

- decreased ability to engage in activities with children[13]

- difficulty sitting[21]

- difficulty standing for 30 minutes or longer[21]

- pain in single leg stance i.e., climbing stairs[21]

- inability or difficulty running (postnatal) due to pain[21]

- decreased ability for mother-child interactions[14]

- pain/discomfort with weight bearing activities[11]

Pain[edit | edit source]

The onset of pain may occur around the 18th week of pregnancy and reaches peak intensity between the 24th and 36th week of pregnancy. The pain typically resolves by the third month in the postpartum period.[22][7]

Location[edit | edit source]

Pelvic girdle pain typically presents near the sacroiliac joints and/or gluteal area or anteriorly near the symphysis pubis[13]. The reported pain may radiate into the patient's groin, perineum or posterior thigh but does not mimic a typically sciatic nerve root distribution.[23][24] The location of the pain may vary throughout the course of the pregnancy.[25] A pain distribution diagram can be a useful tool in identifying the patient's pain and to help distinguish pregnancy-related pelvic girdle pain from pregnancy related low back pain.[26]

Nature and intensity of pain[edit | edit source]

Pelvic girdle pain may be described as a stabbing,[27][28] dull, shooting, or burning sensation.[28] The intensity of pain on a 100 mm visual analogue scale averages around 50-60 mm.[25][24]

Muscle Function and Perception[edit | edit source]

- postpartum women may present with reduced hip abduction and adduction force[29] which may be related to fear of pain/movement.[29]

- women may reported a feeling of "catching" in their upper leg during ambulation[28] and/or report feeling the lack the ability to move their legs during the active straight leg test[30] which may suggest nervous system involvement.[13]

- altered gait coordination - women with postpartum pelvic girdle pain can present with a coupling between pelvic and thoracic rotations during gait (pelvic and thoracic rotations in the same direction occur at the same time) which has been proposed as a nervous system strategy used to cope with motor problems.[31]

Pelvic Girdle Pain Examination[edit | edit source]

Before a diagnosis of pelvic girdle pain is reached potential lumbar spine pain and/or dysfunction should be ruled out.[1] Once the lumbar spine is ruled out the sacroiliac joint, the symphysis pubis, and the pelvis should be assessed.

Sacroiliac joint[edit | edit source]

- Posterior pelvic pain provocation test (P4)[1][20][32] [33]

- Patrick ‘s Faber test [1][20]

- Palpation of the long dorsal SIJ ligament [1][20][32][33]

- Gaenslen’s test [1][20]

- For more information on the tests listed above see SIJ Special Test Cluster

Symphysis Pubis[edit | edit source]

- Palpation of symphysis[1][20][32]

- Modified trendelenburg’s sign of the pelvic girdle [1][20][32]

Functional Pelvic Test[edit | edit source]

- Active straight leg raise test (ASLR test) [1][20][32][33]

Diagnostic Procedures[edit | edit source]

During pregnancy diagnostic imaging using radiation is contraindicated.[26] Ultrasound imaging and/or MRIs may be used for certain interventions and/or surgical planning or to rule out the presence of serious medical conditions.[34]

Outcome Measures[edit | edit source]

The Pelvic Girdle Questionnaire (PGQ)[35] was developed to evaluate impairments and/or the functional limitations caused my pelvic girdle pain during pregnancy and in the postpartum period.[35] The PGQ has been found to significantly discriminated participants who were pregnant from participants who were not pregnant.[36]

Clinton and colleagues[26] recommend using the Pain Catastrophizing Scale (PCS) and the Fear-Avoidance Beliefs Questionnaire (FABQ) when assessing and treating patients with pelvic girdle pain. Using these scales in your clinical practice can help provide you with a broader understanding of your patient's ability to mental process their pain and how their pain is affecting their daily activities. Currently only the Fear-Avoidance Beliefs Questionnaire-Physical Activity sub-scale has been validated for use during pregnancy.[36]

Differential Diagnosis[edit | edit source]

Patient-reported pelvic girdle pain can be associated with signs and symptoms of inflammatory, infectious, traumatic, neoplastic, degenerative, or metabolic disorders.[26] Therefore, it is important to take a detailed subjective history and refer to the appropriate medical professional as indicated. Pelvic girdle pain can be a symptom of uterine abruption or referred pain due to urinary tract infection to the lower abdomen/pelvic or sacral region.[37] A referral to a medical professional is warranted if the patient reports any of the following:[26]

- a history of trauma

- unexplained weight loss

- a history of cancer

- steroid use or drug abuse

- human immunodeficiency virus or immunosuppressed state

- neurological symptoms/signs,

- a fever, and/or feeling systemically unwell

- severe pain that does not improve with rest [26]

[edit | edit source]

When assessing a patient who presents with pregnancy-related pelvic girdle pain the presence of pelvic floor muscle, hip, and lumbar spine dysfunction should be ruled out.[26] Differential diagnoses can include;

Hip dysfunction

- possible femoral neck stress fracture due to transient osteoporosis[38] [39][40]

- bursitis/tendonitis, chondral damage/loose bodies, capsular laxity, femoral acetabular impingement, labral irritations/tears, muscle strains

- referred pain from L2,3 radiculopathy[41]

- osteonecrosis of the femoral head[41]

- Paget’s disease[41]

- rheumatoid, and psoriatic and septic arthritis[41]

Lumbar spine dysfunctions and pregnancy-related low back pain[26]

- spondylolisthesis

- ankylosing spondylitis

- discal patterns of symptoms that fail to centralize

Bowel/bladder dysfunction[26]

- cauda equina syndrome

- large lumbar disc, or

- other space-occupying lesions around the spinal cord or nerve roots

Physical Therapy Management[edit | edit source]

There appears to be theoretical evidence in the research literature to support activity modification and participation in the treatment of pregnancy-related pelvic girdle pain.[26] There is conflicting evidence for the use of support belts, and exercise and the current evidence to support manual therapy is weak.[26] However, clinical experience, knowledge and reasoning should be applied when implementing a treatment plan to address pain, discomfort and dysfunction related to pelvic girdle pain.

Individualized exercise programs[edit | edit source]

The American College of Obstetrics and Gynecologists (ACOG) and the Canadian Clinical Practice Guidelines (CPGs) recommend exercise during and after pregnancy as long as the patient does not present with any contraindications to exercise during their pregnancy. In women who present with pelvic girdle pain during or after their pregnancy, an individualized approach should be taken. Exercise may focus on motor control, strength of the abdominal, spinal, pelvis, and pelvic floor muscles.[42][32] If pelvic floor dysfunction is suspected, referral to a pelvic health physiotherapist is warranted. Aquatic exercises may provide a pain-free environment for women to exercise in during pregnancy.[43]

Manual therapy[edit | edit source]

Manual therapy (i.e., soft tissue mobilization/manipulation, myofascial release, muscle energy, and muscle-assisted range of motion) and massage therapy may provide symptomatic relief[44] and may be incorporated into treatments as required.[26]

Support belts[edit | edit source]

Some patients may find support and/or pain reduction when using support belts.[45] [46] Belts can be worn to improve symptoms and encourage physical activity.

Education and activity modification[edit | edit source]

Physiotherapists should educate their patients on the central pain mechanisms that may be influencing their pain.[47] Encouraging pain-free physical activity and exercise while also educating the patient on the importance of rest and relaxation are essential components of the physiotherapy treatment. Patients should be educated on ergonomics, lifting positions/postures during daily activities and during tasks with the baby and potentially toddlers as well as positions for sexual intercourse.

Prognosis[edit | edit source]

Pregnancy-related pelvic girdle pain appears to be a self-limiting condition that typically resolves by 3 months postpartum in a majority of women.[7] However, due to the complexity of the condition, it has been recommended that a biopsychosocial approach aimed at improving the individual's self-knowledge and self-efficacy be used in the management of pelvic girdle pain to help minimize disability.[48]

Clinical Bottom Line[edit | edit source]

Pregnancy-related pelvic girdle pain is a multifactoral condition that requires a biopsychosocial approach to treat. It is important to rule out any differential diagnoses when assessing patients who present with pelvic girdle pain. Current research and clinical guidelines should be used to inform and assist the physiotherapist's treatment plan for this condition.

Resources[edit | edit source]

A recent study conducted by Dufour and colleagues[47] found that a sample of surveyed physiotherapists were unaware of the current best practices and guidelines that have been published on pregnancy-related pelvic girdle pain.[47] You can access the clinical practice guidelines from Section on Women’s Health and the Orthopaedic Section of the American Physical Therapy Association and the European guidelines in the links below.

Vleeming A, Albert HB, Östgaard HC, Sturesson B, Stuge B. European guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of pelvic girdle pain. European Spine Journal. 2008 Jun 1;17(6):794-819.

References[edit | edit source]

- ↑ 1.00 1.01 1.02 1.03 1.04 1.05 1.06 1.07 1.08 1.09 1.10 1.11 1.12 1.13 Vleeming A, Albert HB, Östgaard HC, Sturesson B, Stuge B. European guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of pelvic girdle pain. European Spine Journal Jun 2008; 17(6) : 794-819.

- ↑ Vleeming A, Schuenke MD, Masi AT, Carreiro JE, Danneels L, Willard FH. The sacroiliac joint: an overview of its anatomy, function and potential clinical implications. Journal of anatomy. 2012 Dec 1;221(6):537-67.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 Raizada V, Mittal RK. Pelvic floor anatomy and applied physiology. Gastroenterology Clinics of North America. 2008 Sep 1;37(3):493-509.

- ↑ Aldabe D, Milosavljevic S, Bussey MD. Is pregnancy related pelvic girdle pain associated with altered kinematic, kinetic and motor control of the pelvis? A systematic review. European Spine Journal. 2012 Sep 1;21(9):1777-87.

- ↑ Homer C, Oats J. Clinical practice guidelines: Pregnancy care. Canberra: Australian Government Department of Health, 2018; p. 355–57

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 6.3 Bhardwaj A, Nagandla K. Musculoskeletal symptoms and orthopaedic complications in pregnancy: Pathophysiology, diagnostic approaches and modern management. Postgrad Med J

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 7.3 7.4 7.5 7.6 7.7 Kanakaris NK, Roberts CS, Giannoudis PV. Pregnancy-related pelvic girdle pain: An update. BMC Med 2011;9:15. doi: 10.1186/1741-7015-9-15.

- ↑ Damen L, Buyruk HM, Güler-Uysal F, Lotgering FK, Snijders CJ, Stam HJ. Pelvic pain during pregnancy is associated with asymmetric laxity of the sacroiliac joints. Acta obstetricia et gynecologica Scandinavica. 2001 Jan 1;80(11):1019-24.

- ↑ Sturesson B, Selvik G, UdÉn A. Movements of the sacroiliac joints. A roentgen stereophotogrammetric analysis. Spine. 1989 Feb;14(2):162-5.

- ↑ Ritchie JR. Orthopedic considerations during pregnancy. Clinical obstetrics and gynecology. 2003 Jun 1;46(2):456-66.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 11.2 Robinson H.S., Clinical course of pelvic girdle pain postpartum - impact of clinic findings in late pregnancy, Manual therapy 19 (2014) 190-196

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 Pierce H, Homer CS, Dahlen HG, King J. Pregnancy-related lumbopelvic pain: listening to Australian women. Nursing research and practice. 2012;2012.

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 13.2 13.3 13.4 13.5 13.6 13.7 13.8 13.9 Wu WH, Meijer OG, Uegaki K, Mens JMA, Van Dieën JH, Wuisman PIJM, Östgaard HC. Pregnancy-related pelvic girdle pain (PPP), I : Terminology, clinical presentation, and prevalence. European Spine Journal Nov 2004; 13(7) : 575-589.

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 Elden H., Predictors and consequences of long-term pregnancy-related pelvic girdle pain: a longitudinal follow-up study,BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2016; 17: 276.doi: 10.1186/s12891-016-1154-0

- ↑ Danielle Casagrande et al., Low Back Pain and Pelvic Girdle Pain in Pregnancy, J Am Acad Orthop Surg 2015;00:1-11

- ↑ Ostgaard HC, Andersson GB. Postpartum low-back pain. Spine. 1992 Jan;17(1):53-5.

- ↑ Bjelland EK. et al., Hormonal contraception and pelvic girdle pain during pregnancy: a population study of 91.721 pregnancies in the norwegian mother and child cohort, Human reproduction. vol 0, No.0 pp1-7, 2013

- ↑ Bergstrom et al., Pregnancy-related low back pain and pelvic girdle pain approximately 14 months after pregnancy – pain status, self-rated health and family situation, BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth 201414:48, DOI: 10.1186/1471-2393-14-48

- ↑ Albert H, Godskesen M, Westergaard J. Prognosis in four syndromes of pregnancy‐related pelvic pain. Acta obstetricia et gynecologica Scandinavica. 2001 Jun 1;80(6):505-10.

- ↑ 20.0 20.1 20.2 20.3 20.4 20.5 20.6 20.7 20.8 Kanakaris NK, Roberts CS, Giannoudis PV. Pregnancy-related pelvic girdle pain: un update. BMC Medicine Feb 2011; 9: 1-15.

- ↑ 21.0 21.1 21.2 21.3 21.4 21.5 Nielsen LL. Clinical findings, pain descriptions and physical complaints reported by women with post-natal pregnancy-related pelvic girdle pain. Acta Obstetricia et Gynecologica 2010: 89; 1187-1191.

- ↑ Oätgaard HC, Andersson GB, Wennergren M. The impact of low back and pelvic pain in pregnancy on the pregnancy outcome. Acta obstetricia et gynecologica Scandinavica. 1991 Jan;70(1):21-4.

- ↑ Fast A, Shapiro D, Ducommun EJ, Friedmann LW, Bouklas T, Floman Y. Low-back pain in pregnancy. Spine. 1987 May;12(4):368-71.

- ↑ 24.0 24.1 Ostgaard HC, Zetherström G, Roos-Hansson E, Svanberg B. Reduction of back and posterior pelvic pain in pregnancy. Spine. 1994 Apr;19(8):894-900.

- ↑ 25.0 25.1 Kristiansson P, Svärdsudd K, von Schoultz B. Back pain during pregnancy: a prospective study. Spine. 1996 Mar 15;21(6):702-8.

- ↑ 26.00 26.01 26.02 26.03 26.04 26.05 26.06 26.07 26.08 26.09 26.10 26.11 Clinton SC, Newell A, Downey PA, Ferreira K. Pelvic Girdle Pain in the Antepartum Population: Physical Therapy Clinical Practice Guidelines Linked to the International Classification of Functioning, Disability, and Health From the Section on Women's Health and the Orthopaedic Section of the American Physical Therapy Association. Journal of Women's Health Physical Therapy. 2017 May 1;41(2):102-25.

- ↑ Östgaard HC, Roos-Hansson E, Zetherström G. Regression of back and posterior pelvic pain after pregnancy. Spine. 1996 Dec 1;21(23):2777-80.

- ↑ 28.0 28.1 28.2 Sturesson et al; Pain pattern in pregnancy and" catching" of the leg in pregnant women with posterior pelvic pain; Spine; 1997; PP 1880-1883

- ↑ 29.0 29.1 Mens JM, Vleeming A, Snijders CJ, Ronchetti I, Stam HJ. Reliability and validity of hip adduction strength to measure disease severity in posterior pelvic pain since pregnancy. Spine. 2002 Aug 1;27(15):1674-9.

- ↑ Mens JM, Vleeming A, Snijders CJ, Koes BW, Stam HJ. Reliability and validity of the active straight leg raise test in posterior pelvic pain since pregnancy. Spine. 2001 May 15;26(10):1167-71.

- ↑ Wu W, Meijer OG, Jutte PC, Uegaki K, Lamoth CJ, de Wolf GS, van Dieën JH, Wuisman PI, Kwakkel G, de Vries JI, Beek PJ. Gait in patients with pregnancy-related pain in the pelvis: an emphasis on the coordination of transverse pelvic and thoracic rotations. Clinical biomechanics. 2002 Nov 1;17(9-10):678-86.

- ↑ 32.0 32.1 32.2 32.3 32.4 32.5 Stuge B, Laerum E, Kirkesola G, Vollestad N. The efficacy of a treatment program focusing on specific stabilizing exercises for pelvic girdle pain after pregnancy: A randomized controlled trial. Spine Feb 2004 : 29(4) ; 351-359.

- ↑ 33.0 33.1 33.2 Vollestad NK, Stuge B. Prognostic factors for recovery from postpartum pelvic girdle pain. European Spine Journal Feb 2009: 18; 718-726.

- ↑ American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, Committee on Obstetric Practice. Guidelines for diagnostic imaging during pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol. 2004;104:647-51.

- ↑ 35.0 35.1 Stuge. B., The pelvic girdle questionnaire: a condition-specific instrument for assessing activity limitations and symptoms in people with pelvic girdle pain. phys ther 2011; 91:1096-1108

- ↑ 36.0 36.1 Grotle M, Garratt AM, Krogstad Jenssen H, Stuge B. Reliability and construct validity of self-report questionnaires for patients with pelvic girdle pain. Physical therapy. 2012 Jan 1;92(1):111-23.

- ↑ Boissonnault JS, Klestinski JU, Pearcy K. The role of exercise in the management of pelvic girdle and low back pain in pregnancy: A systematic review of the literature. Journal of Women’s Health Physical Therapy. 2012 May 1;36(2):69-77.

- ↑ Boissonnault WG, Boissonnault JS. Transient osteoporosis of the hip associated with pregnancy. Journal of Women’s Health Physical Therapy. 2005 Dec 1;29(3):33-9.

- ↑ Møller UK, við Streym S, Mosekilde L, Rejnmark L. Changes in bone mineral density and body composition during pregnancy and postpartum. A controlled cohort study. Osteoporosis International. 2012 Apr 1;23(4):1213-23.

- ↑ Oliveri B , Parisi MS , Zeni S , Mautalen C . Mineral and bone mass changes during pregnancy and lactation . Nutrition . 2004 ; 20 ( 2 ): 235 – 240.

- ↑ 41.0 41.1 41.2 41.3 Tibor LM, Sekiya JK. Differential diagnosis of pain around the hip joint. Arthroscopy. 2008;24(12): 1407–1421.

- ↑ Elden H, Ladfors L, Olsen MF, Ostgaard HC, Hagberg H. Effects of acupuncture and stabilising exercises as adjunct to standard treatment in pregnant women with pelvic girdle pain: randomised single blind controlled trial. Bmj. 2005 Mar 31;330(7494):761.

- ↑ Pennick V, Liddle SD. Interventions for preventing and treating pelvic and back pain in pregnancy. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2013 Aug 1(CD0011):1-00.

- ↑ Khorsan R, Hawk C, Lisi AJ, Kizhakkeveettil A. Manipulative therapy for pregnancy and related conditions: a systematic review. Obstetrical & gynecological survey. 2009 Jun 1;64(6):416-27.

- ↑ Vleeming A, Buyruk HM, Stoeckart R, Karamursel S, Snijders CJ. An integrated therapy for peripartum pelvic instability: a study of the biomechanical effects of pelvic belts. American Journal of Obstetrics & Gynecology. 1992 Apr 1;166(4):1243-7.

- ↑ Mens JM, Damen L, Snijders CJ, Stam HJ. The mechanical effect of a pelvic belt in patients with pregnancy-related pelvic pain. Clin Biomech (Bristol , Avon) 2006; 21(2):122-127.

- ↑ 47.0 47.1 47.2 Dufour S, Daniel S. Understanding Clinical Decision Making: Pregnancy-Related Pelvic Girdle Pain. Journal of Women’s Health Physical Therapy. 2018 Sep 1;42(3):120-7.

- ↑ E.H. Verstraete, G. Vanderstraeten, W. Parewijck. Pelvic Girdle Pain during or after Pregnancy: a review of recent evidence and a clinical care path proposal: a systematic review. Pubmed 2013; 5(1); 33-43