Gait Training in Stroke: Difference between revisions

mNo edit summary |

m (updated information) |

||

| Line 115: | Line 115: | ||

*Increasing safety awareness | *Increasing safety awareness | ||

*Education on proper use of assistive devices | *Education on proper use of assistive devices | ||

====<span>Conventional Gait Training </span>==== | |||

Conventional gait training (over ground gait training) involves breaking down parts of the gait cycle, training and improving the abnormal parts, then reintegrating them into ambulation to return to a more normal gait cycle. This can include the following: | |||

*Symmetrical weight bearing between lower limbs in stance | |||

*Weight shifting between lower limbs | |||

*Stepping training (swinging/clearance) over level and unloved surfaces | |||

*Heel strike/limb loading acceptance | |||

*Single leg stance with stable balance and control | |||

*Push off/initial swing of moving leg | |||

| Line 123: | Line 133: | ||

*Controlling knee and toe paths for toe clearance and foot placement | *Controlling knee and toe paths for toe clearance and foot placement | ||

*Optimizing rhythm and coordination.<ref name="carr" /> | *Optimizing rhythm and coordination.<ref name="carr" /> | ||

Observe for abnormalities of any of these parts and develop therapeutic interventions to improve those skills. | Observe for abnormalities of any of these parts and develop therapeutic interventions to improve those skills. It is important to gather information on a person's normal environment during your evaluation and continued assessment. This information will help shape your gait training plan of care to include skill such as: | ||

* stair and curb negotiation | |||

* ambulation over obstacles | |||

* ambulation over carpet, tile, doorway thresholds | |||

* ambulation over changes in grades such as ramps and slopes | |||

* ambulation over uneven outdoor surfaces such as grass, loose rock, wet surfaces, sidewalks, road surfaces | |||

==== Strength Training ==== | |||

All rehabilitation programs will involve strength training. This can be performed as a formal exercise program or through functional activities. | |||

* Circuit training | |||

* Strength training to improve walking ability | |||

* Task-specific training to improve walking ability'''<br>''' | |||

==== Neuromuscular Reeducation (NMR) ==== | |||

Neurofacilitation techniques to inhibit excessive tone, stimulate muscle activity (if hypotonia is present) and to facilitate normal movement patterns through hands-on techniques.<ref name="janice">Janice J Eng, PhD, PT/OT, Professor and Pei Fang Tang, PhD, PT ;Gait training strategies to optimize walking ability in people with stroke: A synthesis of the evidence; Expert Rev Neurother. Oct 2007; 7(10): 1417–1436.</ref> Practice based on the framework advocated by Berta [[Bobath Approach|Bobath]] remains the predominant physical therapy approach to stroke patients in the UK and is also common in many other parts of the world, including Canada, United States, Europe, Australia, Hong Kong and Taiwan. It has evolved from its original foundations, however elements still emphasize normal tone and the necessity of normal movement patterns to perform functional tasks <ref name="lennon">Lennon S, Baxter D, Ashburn A. Physiotherapy based on the Bobath concept in stroke rehabilitation: a survey within the UK. Disabil Rehabil. 2001;23(6):254–262.</ref>Examples of NMR handling techniques include: | |||

* Neuro Developmental Technique (NDT) | |||

* | * [[Kinesiology Taping-The Basics|Kinesiology taping]] | ||

* | * Neuro-IFRAH | ||

* | |||

== Treadmill Training | ==== Body Weight Supported Treadmill Training ==== | ||

* Body weight supported treadmill training was one of the first translations of the task-specific repetitive treatment concept in gait rehabilitation after stroke.<ref>Stefan Hesse ; Treadmill training with partial body weight support after stroke: A review ; NeuroRehabilitation 22 (2007) 1–11</ref> Through a systematic review of 6 RCTs of Body Weight Supported Treadmill Training (BWSTT) and 2 RCTs without BWSTT, Teasell et al. <ref name="teasell">Teasell RW, Bhogal SK, Foley NC, Speechley MR. Gait retraining post stroke. Top Stroke Rehabil. 2003;10(2):34–65.</ref>concluded that there was conflicting evidence that treadmill training with or without BWSTT resulted in improvements in gait performance over standard treatments. Although the evidence supporting treadmill training appears to be conflicting, two recent clinical practice guidelines recommended that BWSTT be included as an intervention for stroke.<ref name="janice" /><br> | Body Weigh Supported Treadmill Training (BWSTT) | ||

* Turning-based treadmill training has recently been studied as a treatment for stroke gait training. This treadmill is similar to a regular treadmill except for its circular running motor belt (0.8-m radius), which forces patients to continually turn rather than walk straight. Participants walked on the perimeter of the circular belt as it rotated either clockwise or counterclockwise. The finding were interesting. Reporting that EEG-EEG connectivity and EEG-EMG connectivity during walking can be enhanced more by a turning-based treadmill instead of a regular treadmill. Moreover, the improvement in gait symmetry, but not the gait speed, correlated with the modulations in the EEG-EEG and EEG-EMG connectivity over frontal-central-parietal areas of the brain<ref>Chen IH, Yang YR, Lu CF, Wang RY. [https://jneuroengrehab.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12984-019-0503-2 Novel gait training alters functional brain connectivity during walking in chronic stroke patients: a randomized controlled pilot trial.] Journal of neuroengineering and rehabilitation. 2019 Dec;16(1):33. Available from: https://jneuroengrehab.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12984-019-0503-2 (last accessed 29.11.2019)</ref>. | * Body weight supported treadmill training was one of the first translations of the task-specific repetitive treatment concept in gait rehabilitation after stroke.<ref>Stefan Hesse ; Treadmill training with partial body weight support after stroke: A review ; NeuroRehabilitation 22 (2007) 1–11</ref> Through a systematic review of 6 RCTs of Body Weight Supported Treadmill Training (BWSTT) and 2 RCTs without BWSTT, Teasell et al. <ref name="teasell">Teasell RW, Bhogal SK, Foley NC, Speechley MR. Gait retraining post stroke. Top Stroke Rehabil. 2003;10(2):34–65.</ref>concluded that there was conflicting evidence that treadmill training with or without BWSTT resulted in improvements in gait performance over standard treatments. Although the evidence supporting treadmill training appears to be conflicting, two recent clinical practice guidelines recommended that BWSTT be included as an intervention for stroke.<ref name="janice" /><br> | ||

* Turning-based treadmill training has recently been studied as a treatment for stroke gait training. This treadmill is similar to a regular treadmill except for its circular running motor belt (0.8-m radius), which forces patients to continually turn rather than walk straight. Participants walked on the perimeter of the circular belt as it rotated either clockwise or counterclockwise. The finding were interesting. Reporting that EEG-EEG connectivity and EEG-EMG connectivity during walking can be enhanced more by a turning-based treadmill instead of a regular treadmill. Moreover, the improvement in gait symmetry, but not the gait speed, correlated with the modulations in the EEG-EEG and EEG-EMG connectivity over frontal-central-parietal areas of the brain<ref>Chen IH, Yang YR, Lu CF, Wang RY. [https://jneuroengrehab.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12984-019-0503-2 Novel gait training alters functional brain connectivity during walking in chronic stroke patients: a randomized controlled pilot trial.] Journal of neuroengineering and rehabilitation. 2019 Dec;16(1):33. Available from: https://jneuroengrehab.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12984-019-0503-2 (last accessed 29.11.2019)</ref>. | |||

A 2018 systematic review designed to assess the effectiveness of two models of gait re-education in post-stroke patients, namely conventional physical therapy and treadmill training, made the concluding remarks that "if advanced gait re-education methods, requiring costly equipment, cannot be used for various reasons, a well-designed conventional gait training is an adequate, affordable and straightforward method to achieve the intended effects of rehabilitation after stroke." Conventional physical therapy referred to (general exercise program/regular physiotherapy) involved stretching, strengthening, endurance, balance, coordination, range of motion activities, and overground walking practice<ref>Guzik A, Drużbicki M, Wolan-Nieroda A. [https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6548526/ Assessment of two gait training models: conventional physical therapy and treadmill exercise, in terms of their effectiveness after stroke.] Hippokratia. 2018 Apr;22(2):51. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6548526/ (last accessed 29.11.2019)</ref>. | A 2018 systematic review designed to assess the effectiveness of two models of gait re-education in post-stroke patients, namely conventional physical therapy and treadmill training, made the concluding remarks that "if advanced gait re-education methods, requiring costly equipment, cannot be used for various reasons, a well-designed conventional gait training is an adequate, affordable and straightforward method to achieve the intended effects of rehabilitation after stroke." Conventional physical therapy referred to (general exercise program/regular physiotherapy) involved stretching, strengthening, endurance, balance, coordination, range of motion activities, and overground walking practice<ref>Guzik A, Drużbicki M, Wolan-Nieroda A. [https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6548526/ Assessment of two gait training models: conventional physical therapy and treadmill exercise, in terms of their effectiveness after stroke.] Hippokratia. 2018 Apr;22(2):51. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6548526/ (last accessed 29.11.2019)</ref>. | ||

Revision as of 05:58, 24 October 2021

Original Editor - Sheik Abdul Khadir

Top Contributors - Sheik Abdul Khadir, Stacy Schiurring, Kim Jackson, Garima Gedamkar, Lucinda hampton, Naomi O'Reilly, Vanessa Rhule, Evan Thomas, Admin, Simisola Ajeyalemi, Aminat Abolade, 127.0.0.1, WikiSysop, Adam Vallely Farrell, Vidya Acharya, Rucha Gadgil, Wanda van Niekerk and Lauren Lopez

Introduction[edit | edit source]

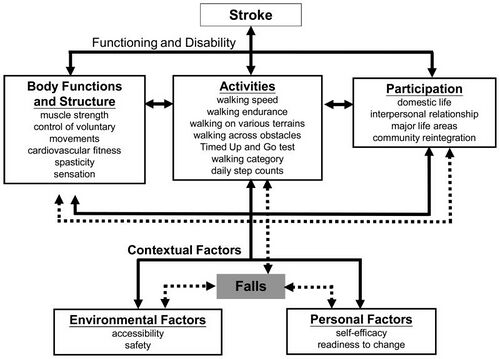

The functional limitations and impairments after a stroke are unique to each individual, however they often include impairments in mobility. Gait recovery is a major objective in the rehabilitation program for persons with stroke, and often a person's top goal. Restoring function after stroke is a complex process involving spontaneous recovery and the effects of therapeutic interventions. Although the majority of persons with a stroke regain the ability to walk, many do not achieve the ambulation endurance, speed, or security required to perform their daily activities independently and safely. Falls are a common concern for community-dwelling persons with stroke[1].

Potential limitations observed after a stroke which effect gait include:

- Muscle weakness of the involved side: Hemiplegia

- Changes in muscle tone: spasticity or flaccidity

- changes in the timing of the gait cycle, resulting in an asymmetrical gait pattern

- decreased walking speed

- changes in the balance systems

- changes in sensation

- changes in visual scanning

- changes in cognition and safety awareness

- soft tissue contracture

Due to the complexities of "normal" gait, skilled personalized therapeutic interventions are needed for successful stroke rehabilitation. Several general principles underpin the process of stroke rehabilitation:

- Good rehabilitation outcome seems to be strongly associated with high degree of motivation, and engagement of the patient and their family.

- Setting goals according to specific rehabilitation aims of an individual might improve the outcomes.

- Cognitive function is strongly related to successful rehabilitation. Attention is a key factor for rehabilitation in persons with stroke as poorer attention performances are associated with a more negative impact of stroke disability on daily functioning[1]

Understanding Normal Gait[edit | edit source]

Gait training, regardless of the client's diagnosis, is based on an understanding of "normal" gait. During a therapy evaluation, it is important to gather information on the person with stroke's baseline level of activity and mobility - this data can be collected from the person themselves or reliable family members or friends. All this information is taken into account when creating a person's individualized therapy program.

Please visit related links as needed for background information: gait cycle, gait disturbances.

The ability to walk independently is a prerequisite for most daily activities, whether a person is homebound or a community distance ambulator. Think of all the skills needed to safely negotiate a community setting: cross a street in the time allotted by pedestrian lights, to step on and off a moving walkway, in and out of automatic doors, avoid obstacles, negotiate curbs, multi-task mobility with environmental scanning, understand the safety signals found in your environment. A walking velocity of 1.1-1.5 m/s is considered normal baseline speed to safely function as a community dwelling individual. It has been reported that only 7% of patients discharged from rehabilitation met the criteria for community walking, which included the ability to walk 500 m continuously at a speed that would enable them to cross a road safely[2].

The major requirements for successful walking[3] include:

- Support of body mass by lower limbs

- Propulsion of the body in the intended direction

- The production of a basic locomotor rhythm

- Dynamic balance control of the moving body

- Flexibility, i.e. the ability to adapt the movement to changing environmental demands and goals.

Gait after Stroke [edit | edit source]

Abnormal gait patterns are a common impairment following a stroke due to disruption of neural pathways in the motor cortex, their communication with the brainstem and its descending pathways and intraspinal locomotor network. This damage results in observed muscle weakness, changes in muscle tone, and abnormal synergistic movement patterns commonly seen in persons with stroke.[4]. Secondary impairments stemming from the cardiovascular and musculoskeletal systems stemming from disuse and physical inactivity can add to ambulation difficulty. The resulting gait pattern following stroke is often a combination of movement deviations and new compensatory movement patterns, unique to that person's injury.[5]. As with all rehabilitation programs, gait training with a person following a stroke is highly individualized. The below video shows an example of progressive intensive individualized gait training.

Typical Kinematic Deviations seen in Gait after Stroke[edit | edit source]

| Gait Deviation | Clinical Observation | |

|---|---|---|

| Initial Stance | Limited ankle dorsiflexion |

|

| Lack of knee flexion (knee hyperextension) |

| |

| Midstance | Lack of Knee Extension (knee remains flexed 10-150 with excessive ankle dorsiflexion) |

|

| Knee Hyperextension (This interferes with preparation for push-off ) | contracture of soleus (an adaptation to fear of limb collapse due to weakness of muscles controlling the knee) | |

| Limited hip extension and ankle dorsiflexion with failure to progress body mass forward over the foot | contracture of soleus | |

| Excessive Lateral Pelvic Shift | decreased ability to activate stance hip abductors and control hip and knee extensors | |

| Late Stance (Pre-swing) | Lack of Knee Flexion and Ankle Plantar-flexion (prerequisites for push-off and preparation for swing) | weakness of calf muscles |

| Early and Mid-swing | Limited Knee Flexion normally 35-40° increasing to 60° for swing and toe clearance |

|

| Late-swing | Limited Knee Extension and Ankle Dorsiflexion jeopardising heel contact and weight-acceptance |

|

As can be seen in the above videos, the persons with stroke demonstrated the following spatiotemporal adaptations: decreased walking speed, short and/or uneven step and stride lengths, increased stride width, increased double support phase, and dependence on assistive device through the hands.[7]

Gait Training [edit | edit source]

Therapeutic Interventions[edit | edit source]

Stroke rehabilitation is highly individualized to a person with stroke's needs. A physical therapy plan of care can include any or all of the following interventions to improve ambulation ability:

- Preventing adaptive changes in lower limb soft tissues

- Eliciting voluntary activation in key muscle groups in lower limbs

- Increasing muscle strength and coordination

- Increasing walking velocity and endurance

- Maximizing skill, eg increasing flexibility

- Increasing static and dynamic balance

- Increasing cardiovascular fitness

- Increasing safety awareness

- Education on proper use of assistive devices

Conventional Gait Training [edit | edit source]

Conventional gait training (over ground gait training) involves breaking down parts of the gait cycle, training and improving the abnormal parts, then reintegrating them into ambulation to return to a more normal gait cycle. This can include the following:

- Symmetrical weight bearing between lower limbs in stance

- Weight shifting between lower limbs

- Stepping training (swinging/clearance) over level and unloved surfaces

- Heel strike/limb loading acceptance

- Single leg stance with stable balance and control

- Push off/initial swing of moving leg

The following components of gait are key to successful ambulation:

- Support of the center of gravity (COG) by the lower limbs

- Propulsion of the COG by the lower limbs

- balance of the COG as it transitions between weight bearing limbs

- Controlling knee and toe paths for toe clearance and foot placement

- Optimizing rhythm and coordination.[7]

Observe for abnormalities of any of these parts and develop therapeutic interventions to improve those skills. It is important to gather information on a person's normal environment during your evaluation and continued assessment. This information will help shape your gait training plan of care to include skill such as:

- stair and curb negotiation

- ambulation over obstacles

- ambulation over carpet, tile, doorway thresholds

- ambulation over changes in grades such as ramps and slopes

- ambulation over uneven outdoor surfaces such as grass, loose rock, wet surfaces, sidewalks, road surfaces

Strength Training[edit | edit source]

All rehabilitation programs will involve strength training. This can be performed as a formal exercise program or through functional activities.

- Circuit training

- Strength training to improve walking ability

- Task-specific training to improve walking ability

Neuromuscular Reeducation (NMR)[edit | edit source]

Neurofacilitation techniques to inhibit excessive tone, stimulate muscle activity (if hypotonia is present) and to facilitate normal movement patterns through hands-on techniques.[9] Practice based on the framework advocated by Berta Bobath remains the predominant physical therapy approach to stroke patients in the UK and is also common in many other parts of the world, including Canada, United States, Europe, Australia, Hong Kong and Taiwan. It has evolved from its original foundations, however elements still emphasize normal tone and the necessity of normal movement patterns to perform functional tasks [10]Examples of NMR handling techniques include:

- Neuro Developmental Technique (NDT)

- Kinesiology taping

- Neuro-IFRAH

Body Weight Supported Treadmill Training [edit | edit source]

Body Weigh Supported Treadmill Training (BWSTT)

- Body weight supported treadmill training was one of the first translations of the task-specific repetitive treatment concept in gait rehabilitation after stroke.[11] Through a systematic review of 6 RCTs of Body Weight Supported Treadmill Training (BWSTT) and 2 RCTs without BWSTT, Teasell et al. [12]concluded that there was conflicting evidence that treadmill training with or without BWSTT resulted in improvements in gait performance over standard treatments. Although the evidence supporting treadmill training appears to be conflicting, two recent clinical practice guidelines recommended that BWSTT be included as an intervention for stroke.[9]

- Turning-based treadmill training has recently been studied as a treatment for stroke gait training. This treadmill is similar to a regular treadmill except for its circular running motor belt (0.8-m radius), which forces patients to continually turn rather than walk straight. Participants walked on the perimeter of the circular belt as it rotated either clockwise or counterclockwise. The finding were interesting. Reporting that EEG-EEG connectivity and EEG-EMG connectivity during walking can be enhanced more by a turning-based treadmill instead of a regular treadmill. Moreover, the improvement in gait symmetry, but not the gait speed, correlated with the modulations in the EEG-EEG and EEG-EMG connectivity over frontal-central-parietal areas of the brain[13].

A 2018 systematic review designed to assess the effectiveness of two models of gait re-education in post-stroke patients, namely conventional physical therapy and treadmill training, made the concluding remarks that "if advanced gait re-education methods, requiring costly equipment, cannot be used for various reasons, a well-designed conventional gait training is an adequate, affordable and straightforward method to achieve the intended effects of rehabilitation after stroke." Conventional physical therapy referred to (general exercise program/regular physiotherapy) involved stretching, strengthening, endurance, balance, coordination, range of motion activities, and overground walking practice[14].

Biofeedback[edit | edit source]

Forms of biofeedback have been in use in physical therapy for more than 50 years, where it is beneficial in the management of neuromuscular disorders. Biofeedback techniques have shown benefit when used as part of a physical therapy program for people with motor weakness or dysfunction after stroke. These methods are getting better at training for complex task-oriented activities like walking and grasping objects as technology continues to advance.[15]

Functional Electrical Stimulation[edit | edit source]

- Functional Electrical Stimulation (FES) is a useful methodology for the rehabilitation after stroke, along or as a part of a Neuro-robot.

- FES consists on delivering an electric current through electrodes to the muscles. The current elicits action potentials in the peripheral nerves of axonal branches and thus generates muscle contractions.

- FES has been used in rehabilitation of chronic hemiplegia since the 1960s.[1]

Robotic-Assisted Training[edit | edit source]

Robotic devices provide safe, intensive and task-oriented rehabilitation to people with mild to severe neurologic injury. It does

- precisely controllable assistance or resistance during movements

- good repeatability

- objective and quantifiable measures of subject performance,

- increased training motivation through the use of interactive (bio)feedback.

In addition, this approach reduces the amount of physical assistance required to walk reducing health care costs and provides kinematic and kinetic data in order to control and quantify the intensity of practice, measure changes and assess motor impairments with better sensitivity and reliability than standard clinical scales.[16]

Conclusions[edit | edit source]

After stroke, gait recovery is a major objective in the rehabilitation program, therefore a wide range of strategies and assistive devices have been developed for this purpose. However, estimating rehabilitation effects on motor recovery is complex, due to the interaction of spontaneous recovery, whose mechanisms are still under investigation, and therapy.

The approaches used in gait rehabilitation after stroke include neurophysiological and motor learning techniques, robotic devices, FES, and the new evolving use of Brain Computer Interface. Brain-Computer Interface systems record, decode, and translate some measurable neurophysiological signal into an effector action or behavior. Therefore BCIs are potentially a powerful tool.[1]

References[edit | edit source]

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 Belda-Lois JM, Mena-del Horno S, Bermejo-Bosch I, Moreno JC, Pons JL, Farina D, Iosa M, Molinari M, Tamburella F, Ramos A, Caria A. Rehabilitation of gait after stroke: a review towards a top-down approach. Journal of neuroengineering and rehabilitation. 2011 Dec 1;8(1):66.Available from:https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3261106/ (last accessed 5.2.2020)

- ↑ Hill K, Ellis P, Bernhardt Jet al. (1997) Balance and mobility outcomes for stroke patients: a comprehensive audit. Aust J Physiother, 43, 173-180.

- ↑ Forssberg H (1982) Spinal locomotion functions and descending control. In Brain Stem Control of Spinal Mechanisms (eds B Sjolund, A Bjorklund), Elsevier Biomedical Press,New York.

- ↑ Li S, Francisco GE, Zhou P. Post-stroke hemiplegic gait: new perspective and insights. Frontiers in physiology. 2018;9:1021. Available from: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fphys.2018.01021/full (last accessed 29.11.2019)

- ↑ Balaban, Birol et al.:Gait Disturbances in Patients With Stroke : PM&R , Volume 6 , Issue 7 , 635 - 642

- ↑ H Hayes Hospital Physical Therapy Restores Walking After Stroke Available from: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=g__BYaS9viw (last accessed 29.11.2019)

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 Janet H Carr EdD FACP , Roberta B Shepherd EdD FACP; Stroke Rehabilitation- Guidelil1es for Exercise and Training to Optimize Motor Skill ; First edition; 2003

- ↑ Hemiplegic Gait – Case Study 13 Available from: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ihz74Zv6D84last accessed 23.10.2021)

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 Janice J Eng, PhD, PT/OT, Professor and Pei Fang Tang, PhD, PT ;Gait training strategies to optimize walking ability in people with stroke: A synthesis of the evidence; Expert Rev Neurother. Oct 2007; 7(10): 1417–1436.

- ↑ Lennon S, Baxter D, Ashburn A. Physiotherapy based on the Bobath concept in stroke rehabilitation: a survey within the UK. Disabil Rehabil. 2001;23(6):254–262.

- ↑ Stefan Hesse ; Treadmill training with partial body weight support after stroke: A review ; NeuroRehabilitation 22 (2007) 1–11

- ↑ Teasell RW, Bhogal SK, Foley NC, Speechley MR. Gait retraining post stroke. Top Stroke Rehabil. 2003;10(2):34–65.

- ↑ Chen IH, Yang YR, Lu CF, Wang RY. Novel gait training alters functional brain connectivity during walking in chronic stroke patients: a randomized controlled pilot trial. Journal of neuroengineering and rehabilitation. 2019 Dec;16(1):33. Available from: https://jneuroengrehab.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12984-019-0503-2 (last accessed 29.11.2019)

- ↑ Guzik A, Drużbicki M, Wolan-Nieroda A. Assessment of two gait training models: conventional physical therapy and treadmill exercise, in terms of their effectiveness after stroke. Hippokratia. 2018 Apr;22(2):51. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6548526/ (last accessed 29.11.2019)

- ↑ Malik K, Dua A. Biofeedback. [Updated 2019 Dec 20]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2020 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK553075/

- ↑ Juan-Manuel Belda-Lois et al; Rehabilitation of gait after stroke: a review towards a top-down approach ;Journal of NeuroEngineering and Rehabilitation 2011, 8:66

- ↑ Walkbot. Walkbot - Walking Available from:https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=rbPfnDIBOvI [last accessed 18/09/2016]