Fracture

Top Contributors - Esraa Mohamed Abdullzaher, Naomi O'Reilly, Kalyani Yajnanarayan, Lucinda hampton, Khloud Shreif, Kim Jackson, Claire Knott, Abbey Wright and Aminat Abolade

Definition[edit | edit source]

A fracture is a discontinuity in a bone (or cartilage) resulting from mechanical forces that exceed the bone's ability to withstand them.[1] Fractures can occur in a variety of settings;

- A normal bone subjected to acute overwhelming force, usually in the setting of trauma

- Weakened bone due to metabolic abnormalities (e.g. osteoporosis) or less frequently, genetic abnormalities (e.g. osteogenesis imperfecta). Resulting in insufficiency fractures.

- The protracted chronic application of abnormal stresses (e.g. running) can result in the accumulation of microfractures faster than the body can heal, eventually resulting in macroscopic failure. These are termed fatigue fractures. Nb. Together, insufficiency and fatigue fractures are often grouped together as stress fractures.

- The bone may have a lesion that focally weakens a bone (e.g. metastasis, or bone cyst). These are known as pathological fractures.

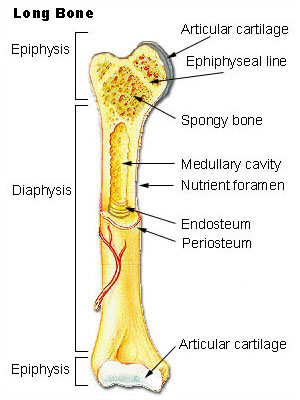

Location[edit | edit source]

Type of Bone Fractured

- long bone (femor, humerus)

- short bone (carpal bones),

- flat bone (scapulae, ribs)

- Sesamoid bone as in patella

- Irregular bone (vertebrae and skull)

Part of Bone Fractured

- Epiphysis

- Physis

- Metaphysis

- Diaphysis; or

- Specific Features within a bone (tubercle, epicondyle)

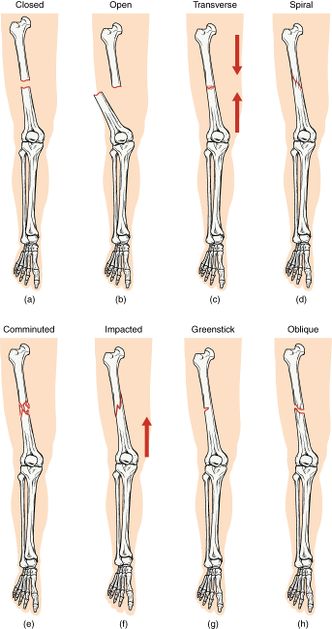

Types of Bone Fracture[edit | edit source]

In general, there are many different classification systems used for fractures, which can be based on the position of the ends of the fractured bone in relation to each other (displaced or non-displaced), whether the fracture extends all the way across the bone (complete or incomplete), the orientation of the fracture (transverse or vertical) or the penetration of the skin (simple or compound, open or closed) or specific to children (bowing, buckling, and greenstick). Fractures usually fall within a set number of patterns:

- Complete: Extends all the way across the bone (most common)

- Incomplete: does not cross the bone completely (usually encountered in children)

- Non-Displaced / Stable: Fractured ends of the bone line up

- Displaced / Unstable: Fractured portions of bone are separated or misaligned.

- Closed / Simple:Bone has not pierced the skin

- Open / Compound: Skin has been pierced or punctured by the bone or by a blow that breaks the skin at the time of the fracture. The bone or may not be visible.

- Transverse: Fracture is in a straight line across or perpendicular to axis of bone

- Oblique: Fracture is orientated obliquely across the bone

- Spiral: Fracture spirals around the bone, or a helical fracture path usually in the diaphysis of long bones, common in twisting injuries.

- Stress: Small crack or severe bruising within a bone

- Comminuted: Fracture is in three or more pieces with fragments present at site

- Compression: Bone is crushed causing the fractured bone to be wider or flatter in appearance

- Segmental: Same bone is fractured in two places so there is ‘floating’ segment of bone

- Bowing: Incomplete fracture of long bone in infants/children due to forces in the axial load[2].

- Buckle Fracture: Due to direct axial load, the cortex is buckled, often in the distal radius

- Greenstick Fracture: Fracture in a young, soft bone in which the bone bends and the cortex is broken, but only on one side[1]

Pathophysiology of Bone Healing[edit | edit source]

The pathophysiological sequence of events that occur following a fracture for bone healing can be divided into three main phases[3][4]: 1) Inflammatory Phase, 2) Reparative Phase and 3) Remodelling Phase

Phase 1 - Inflammatory Phase (Hours - Days)[edit | edit source]

The inflammatory reaction results in the release of cytokines, growth factors and prostaglandins, all of which are important in healing. Immediately at the time of fracture, the space between fracture ends is filled with blood-forming a heamatoma, which stops additional bleeding, becomes organised to provides structural and biochemical support for the influx of inflammatory cells, fibroblasts, chondroblasts and the ingrowth of capillaries and is then infiltrated by fibrovascular tissue, which forms a matrix for bone formation and primary callus. This process takes approximately a week, forming a primary callus which is non-mineralized and not readily visible on radiography

Phase 2 - Reparative Phase (Days - Weeks)[edit | edit source]

Over the next few weeks, this primary callus is transformed into a bony callus by the activation of osteoprogenitor cells. These cells lay down woven bone which stabilises the fracture site, which can be seen on radiographs within 7-10 days after injury.

Soft callus is organised and remodelled into hard callus over several weeks. Soft callus is plastic and can easily deform or bend if the fracture is not adequately supported. Hard callus is weaker than normal bone but is better able to withstand external forces and equates to the stage of "clinical union", i.e. the fracture is not tender to palpation or with movement.

Phasde 3 - Remodelling Phase (Months to Years)[edit | edit source]

This is the longest phase and may last for several years, and represents the gradual formation of compact cortical bone with greater biomechanical properties and allows for the reduction of the width of the callus. During remodelling, the healed fracture and surrounding callus responds to activity, external forces, functional demands and growth. Bone (external callus) which is no longer needed is removed and the fracture site is smoothed and sculpted. Remodelling can result in almost perfect healing, however, where alignment of the fracture site is not perfect, a residual deformity may remain.[1]

Complications[edit | edit source]

Many of the aforementioned fracture types can also go on to have additional complicating features (and many associated soft tissue injuries) See Fracture Complications

- Acute Compartment Syndrome is common in the fracture of the forearm.

- Fat embolism syndrome (a piece of fat that released into the blood vessels causing blockage of blood flow) [6] that is most commonly associated with long bone and pelvic fracture[7]

- Osteomyelitis of bone in response to infection.

- Healing complications: malunion, delayed union, or nonunion. [8]

- Avascular Necrosis

- Fracture Blisters

- Compound Fracture: extending through the skin

- Joint Involvement: intracapsular; articular; dislocation

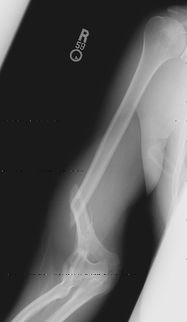

Clinical Features of Fracture[edit | edit source]

Clinical features vary depending on the cause and nature of the injury and range from unconsciousness to the patient being able to use the limb, although complaining of pain. These features are :

- Pain (Image at arm following a boxing injury, painful)

- Deformity

- Oedema

- Loss of Function

- Muscle Spasm

- Muscle Atrophy

- Abnormal Movement

- Limitation in Joint Range of Motion

- Shock

When Is Fracture Healed[edit | edit source]

The average time for bone healing is about 6-8 weeks, but it varies depending upon many factors, including :

Local Factors

- The severity of bone fractured, the type of fracture sustained, and to what extent the misalignment of the fractured bone.

- Infection, that can lead to delayed, poor, or non-union healing.

- The blood supply to the fractured bone.

- The type of fixation, it is a cast, splint, or it is ORIF procedure.

Systemic Factors

- The age of the person, for example, people with osteoporosis predisposes more to healing complications.

- The nutritional status of the person.

- Smoking, it causes delayed healing

- The treatment undergone.[10]

A fracture is considered to be clinically healed based upon the combination of physical findings and symptoms over time. The following suggest complete healing :

- Absence of pain on weight-bearing, lifting or movement

- No tenderness on palpation at the fracture site

- Blurring or disappearance of the fracture line on X-ray

- Full or near full functional ability[11].

Treatment and Prognosis[edit | edit source]

The basics of fracture healing rely on alignment and immobilisation.

Alignment may or may not be necessary depending on the degree of displacement, the importance of correct alignment (e.g. index finger vs rib), and the patient (e.g. professional athlete vs debilitated elderly).

Immobilisation can be achieved in a variety of ways depending on the location, morphology of the fracture, and device of fixation

- None (e.g. most rib fractures)

- Sling (e.g. many clavicular fractures)

- Cast (e.g. many forearm fractures)

- Internal fixation (e.g. most hip fractures)

- External fixation

Fixation Devices[edit | edit source]

Stress Sharing Devices[edit | edit source]

It allows micromotion between the two fractured sites and partial transmission of load, so promote secondary bone healing with callus formation, which is a relatively rapid bone healing.

For example; intramedullary nail, casts, rods.

Stress Shielding Devices[edit | edit source]

The stress at the fracture site is transmitted through the shielding device, there is no motion at the fracture site so promote primary bone healing without callus formation, which is slower than the healing with callus formation.

For example; compression plate[12][13].

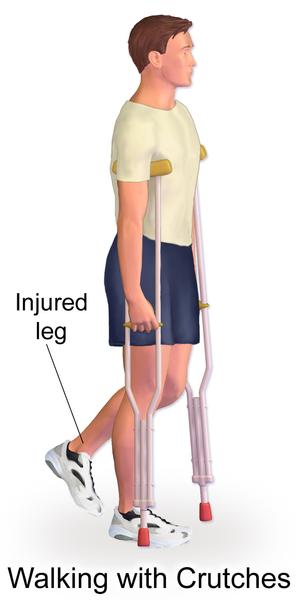

Role of Physiotherapy[edit | edit source]

The physiotherapist’s role is to identify the cause of the problem and to select the appropriate procedure to alleviate or eliminate the cause of the loss of movement. Examples of early treatment include

- A physical therapist may instruct the client how to walk with an assistive device, like a cane or crutches. This includes how to use the device to walk up and down stairs or to get into and out of a car. Learning a new skill takes practice, so be sure to allow client practice using your device while they are with you.

- After a lower extremity fracture there may limit the amount of weight client can put on the leg. Help the client understand weight bearing restrictions and teach how to move about while still maintaining these restrictions.

- If the fracture is in the arm, you as the physical therapist may teach you how to apply and remove the sling

Doing an assessment for the patient is necessary also doing The problem-oriented medical record (POMR) system ( is based on a data collection system that incorporates the acronym SOAP:

- Subjective – any information given to you by the patient: allergies, past medical history, past surgical history, family history, social history (living arrangements, social conditions, employment, medication), review of systems .

- Objective – all information obtained through observation or testing, e.g. range of joint movement, muscle strength .

- Analysis – a listing of problems based on what you know from a review of subjective and objective data.

- Plan – this refers to the plan of treatment).

Also By Using specific exercises, the aim is to reduce any swelling, regain full muscle power and joint movement, and to bring back full function. The treatment will depend very much on the problems identified during your initial assessment, but may include a mixture of the following:

- Soft tissue massage, particularly to manage Edema and swelling

- Scar management if the patient had surgery to fix the fracture

- Ice therapy

- Stretching exercises to regain joint range of movement

- Joint manual therapy and mobilizations to assist in regaining joint mobility

- Structured and progressive strengthening regime

- Balance and control work and gait (walking) re-education where appropriate

- Taping to support the injured area/help with swelling management

- Return to sport preparatory work and advice where required[11]

References[edit | edit source]

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 Radiopedia Fracture Available from:https://radiopaedia.org/articles/fracture-1 (last accessed 2.4.2020)

- ↑ https://radiologykey.com/types-of-fractures-in-children/

- ↑ Bahney CS, Zondervan RL, Allison P, Theologis A, Ashley JW, Ahn J, Miclau T, Marcucio RS, Hankenson KD. Cellular biology of fracture healing. Journal of Orthopaedic Research®. 2019 Jan;37(1):35-50.

- ↑ Kostenuik P, Mirza FM. Fracture healing physiology and the quest for therapies for delayed healing and nonunion. Journal of Orthopaedic Research®. 2017 Feb;35(2):213-23.

- ↑ Whats Up Dude. How Does A Bone Break Heal - Bone Fracture Healing Process. Available from: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=od8oU5OLMGU[last accessed 8/6/2020]

- ↑ Maitre S. Causes, clinical manifestations, and treatment of fat embolism. AMA Journal of Ethics. 2006 Sep 1;8(9):590-2.

- ↑ Hershey K. Fracture complications. Critical Care Nursing Clinics. 2013 Jun 1;25(2):321-31.

- ↑ Jackson LC, Pacchiana PD. Common complications of fracture repair. Clinical techniques in small animal practice. 2004 Aug 1;19(3):168-79.

- ↑ Jay Cheon. Complications of fractures. Available from: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=RKScXgsYXwk[last accessed 8/6/2020]

- ↑ Sheen JR, Garla VV. Fracture Healing Overview. InStatPearls [Internet] 2019 Nov 25. StatPearls Publishing.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 Tidy's Physiotherapy Chapter 22 Churchill Livingstone Elsevier London 2013

- ↑ Burgoyne W. Treatment and rehabilitation of fractures. Edited by Stanley Hoppenfeld and Vasantha L. Murthy. Pp 574. Hagerstown, Maryland: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 2000. ISBN: 0-7817-2197-0. $69.95.

- ↑ http://chambalravine.blogspot.com/2013/07/biomechanical-principles-of-fracture.html