Effects of Ageing on Bone

Original Editor Oyemi Sillo

Top Contributors - Lucinda hampton, Esraa Mohamed Abdullzaher, Oyemi Sillo, Andeela Hafeez, Tolulope Adeniji, Kim Jackson, Lauren Lopez, Tony Lowe, Scott Buxton, WikiSysop and Jasrah JavedIntroduction[edit | edit source]

As a result of the aging process, bone deteriorates in composition, structure and function, which predisposes to osteoporosis. Bone is a dynamic organ that serves mechanical and homeostatic functions. It undergoes a continual self-regeneration process called remodeling ie removing old bone and replacing it with new bone. Bone formation and bone resorption is coupled tightly in a balance to maintain bone mass and strength. With aging this balance shifts in a negative direction, favoring greater bone resorption and less bone formation. This combination of bone mass deficiency and reduction in strength ultimately results in osteoporosis and fractures.[1]

Ageing Bone Dynamics[edit | edit source]

As people age the rate of bone resorption by osteoclast cells (multinucleated cells which contain mitochondria and lysosomes that is responsible for bone resorption) exceeds the rate of bone formation so bone weaken.[2] The reasons for this are multi factorial, including:.

Non-Modifiable Risk Factor

- Genetic factor

- Caucasian race

- Hispanic women

- Older than 50 years of age

- Family history of osteoporosis

- Comorbid medical conditions eg Hyperthyroidism, Hyperparathyroidism

- Premature birth

- Low levels of estrogen

- Childhood malabsorption disease

- Age-related loss of muscle mass

- Seizure disorder[3]

genetics, peak bone mass accrual in youth, alterations in cellular components, hormonal, biochemical and vasculature status.

Modifiable Risk Factor

- Nutrition eg Calcium intake of less than 1200 mg/day, Insufficient protein intake, Inadequate Vitamin D intake, BMI <18.5,

- Physical activity,

- Drugs eg Excessive intake of alcohol, Cigarette smoking[3][1]

Effects of Changes in Aging Bone[edit | edit source]

Osteoporosis is a common problem among older people, especially post-menopausal women, and is a major cause of hip fractures in the elderly.

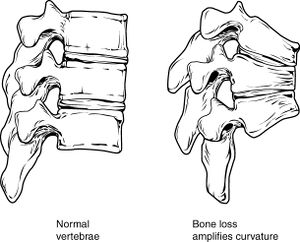

Reduced bone density of the vertebrae, combined with the loss of fluid in intervertebral discs, result in a curved and shortened trunk. This reduced bone density, and resulting poor posture, leads to pain, reduced mobility, and other musculoskeletal problems.

The risk of injury increases because gait changes, instability, and loss of balance may lead to falls.[4][5]

Prevention[edit | edit source]

Exercise is important for preserving bone density, however care must be taken to avoid high-impact exercises and exercises that present the risk of falling. Useful exercises include:

- Weight-bearing exercises e.g. walking

- Strengthening exercises using free weights, elastic bands, dumbbells etc.

- Balance exercises e.g. tai chi

A healthy diet, including adequate dosage of Vitamin D and Calcium, is also useful for preserving bone mass. And it is important to limit coffee, alcohol and tobacco consumption as they may have deleterious effect on bone mineral density[6][7].

For more see the informative osteoporosis page.

Exercise and Ageing[edit | edit source]

Exercise is wonderful for health — but to get gain without pain, you must do it wisely, using restraint and judgment every step of the way. Here are a few tips:

- Get a medical check-up before you begin a moderate to vigorous exercise program, particularly if you are older than 40, if you have medical problems, or if you have not exercised previously.

- Eat and drink appropriately. Don’t eat large meals for one hour before you exercise, drink plenty of water before, during, and after exercise, particularly in warm weather.

- Warm up before you exercise and cool down afterward.

- Dress simply, aiming for comfort, convenience, and safety rather than style.

- Use good equipment, especially good shoes.

- Exercise regularly.

- Listen to your body. Learn warning signals of heart disease, including chest pain or pressure, disproportionate shortness of breath, fatigue, or sweating, erratic pulse, lightheadedness, or even indigestion. Do not ignore aches and pains that may signify injury; early treatment can often prevent more serious problems. Do not exercise if you are feverish or ill. Work yourself back into shape gradually after a layoff, particularly after illness or injury.[8]

It is important to note that in other to improve bone mineral density it requires combination of several types of exercises majorly resistance training. Kawao & Kaji [9] noted that while in healthy bone resistance training maintains and improves bone mineral density(BMD)and bone strength, however, in osteoporosis patients it takes resistance training with other types of exercises to maintain BMD.

References[edit | edit source]

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Demontiero O, Vidal C, Duque G. Aging and bone loss: new insights for the clinician. Therapeutic advances in musculoskeletal disease. 2012 Apr;4(2):61-76. Available: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3383520/ (accessed 2.12.2022)

- ↑ https://www.boundless.com/physiology/textbooks/boundless-anatomy-and-physiology-textbook/appendix-b-development-and-aging-of-the-organ-systems-1417/bone-development-1497/bone-tissue-and-the-effects-of-aging-1500-11222/

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 Andrew A, Rita A, Dale A. Geriatric Physical Therapy. Third Edition. Elsevier Mosby. 2012

- ↑ http://www.nlm.nih.gov/medlineplus/ency/article/004015.htm

- ↑ https://medlineplus.gov/ency/article/004015.htm

- ↑ http://www.nlm.nih.gov/medlineplus/ency/article/000360.htm

- ↑ Coronado-Zarco R, de León AO, García-Lara A, Quinzaños-Fresnedo J, Nava-Bringas TI, Macías-Hernández SI. Nonpharmacological interventions for osteoporosis treatment: Systematic review of clinical practice guidelines. Osteoporosis and sarcopenia. 2019 Sep 1;5(3):69-77.

- ↑ http://www.health.harvard.edu/newsweek/Exercise_and_aging_Can_you_walk_away_from_Father_Time.htm

- ↑ Kawao, N., & Kaji, H. (2017). Influences of resistance training on bone. Clinical calcium, 27(1), 73-78.