Atrial Fibrillation

Top Contributors - Paul McDermott, James Moore, Lucinda hampton, Kim Jackson, Adam Vallely Farrell, Elaine Lonnemann, George Prudden, WikiSysop, Karen Wilson and Vidya Acharya

Introduction[edit | edit source]

Atrial fibrillation is a common disease that affects many individuals. The prevalence of this disease increases with age with the most severe complication being acute CVA. Due to the irregularly of the atria, blood blow through this chamber becomes turbulent leading to a blood clot (thrombus). This thrombus is commonly found in the atrial appendage. The thrombus can dislodge and embolize to the brain and other parts of the body. It is important for the patient to seek medical care immediately if they are experiencing chest pain, palpitations, shortness of breath, severe sweating, or extreme dizziness.[1]

Definition/Description[edit | edit source]

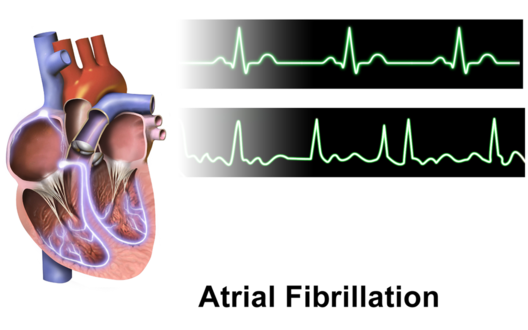

Atrial fibrillation (AF) is the most common type of heart arrhythmia. During atrial fibrilation the heart can beat too fast, too slow, or with an irregular rhythm.

AF occurs when rapid, disorganised electrical signals cause the heart's two upper chambers known as the atria to fibrillate. The term "fibrillate" means that a muscle is not performing full contractions. Instead, the cardiac muscle in the atria is quivering at a rapid and irregular pace. This ultimately leads to blood pooling in the atria as it is not completely pumped out of the atria into the two lower chambers known as the ventricles.[2]

Etiology[edit | edit source]

There are many causes of atrial fibrillation. Advanced age, congenital heart disease, underlying heart disease (valvular disease, coronary artery disease, structural heart disease), increased alcohol consumption, hypertension, and obstructive sleep apnea are all common causes of atrial fibrillation. Any process that causes inflammation, stress, damage, and ischemia to the structure and electrical system of the heart can lead to the development of atrial fibrillation. In some cases, the cause is iatrogenic.[1]

Atrial Fibrillation is a common early postoperative complication of cardiac and thoracic surgery.

Etiology includes:

- Alcohol use (Holiday syndrome)

- Caffeine

- High fevers

- Severe infection

- Pneumonia

- Chronic gastritis caused by chronic H. pylori infection

- Emotional stress

- Myocardial Infarction

- Pericarditis

- Pericardial disease

- Myocarditis

- Pulmonary Embolism

- Electrocution

- Hyperthyroidism (up to 15%)

- Thyrotoxicosis

- Kidney disease

- Electrolyte abnormalities

- Increasing age

- Mitral valve disease

- Conduction system disorders

- Wolff-Parkinson-White syndrome

- Hypothermia

- Hypoxia

- Digoxin toxicity[3][4][5][6][7]

The 3 patterns of atrial fibrillation include:

- Paroxysmal AF: Here the episodes terminate spontaneously within 7 days.

- Persistent AF: The episodes last more than 7 days and often require electrical or pharmacological interventions to terminate the rhythm

- Long-standing persistent AD: rhythm that has persisted for more than 12 months, either because a pharmacological intervention has not been tried or cardioversion has failed.[1].

Epidemiology/Prevalence[edit | edit source]

- The prevalence of atrial fibrillation has been increasing worldwide. It is known that the prevalence of atrial fibrillation generally increases with age. "An estimated 2.7–6.1 million people in the United States have AF. With the aging of the U.S. population, this number is expected to increase.[8]

- It has been estimated that the number of individuals with atrial fibrillation will double or triple by the year 2050.

- Although the world white prevalence of atrial fibrillation is approximately 1%, approximately 2% of people younger than age 65 have AF.[8] and approximately 9% in individuals over the age of 75.

- At the age of 80, the lifetime risk of developing atrial fibrillation jumps to 22%.

- Atrial fibrillation has more commonly been associated with males and seen more often in whites as compared to black[1].

- AF without associated heart disease: Approximately 30% to 45% of cases of paroxysmal AF and 20% to 25% of cases of persistent AF occur in young patients without demonstrable underlying disease. This is considered lone AF although, over the course of time, an underlying disease that may be causing the atrial fibrillation may appear.[9]

- "African Americans are less likely than those of European descent to have AF.[8]

Pathophysiology[edit | edit source]

There are a wide variety of pathophysiology mechanisms that play a role in the development of atrial fibrillation. Most commonly, hypertension, structural, valvular, and ischemic heart disease illicit the paroxysmal and persistent forms of atrial fibrillation but the underlying pathophysiology is not well understood. Some research has shown evidence of genetic causes of atrial fibrillation involving chromosome 10.[1]

AF may occur due to:

- Old age, without underlying heart disease. Changes in cardiac structure and function that accompany the aging process, such as increased myocardial stiffness, may be associated with AF.[3]

- Atrial factors: Any kind of structural heart disease may trigger remodeling of the heart. Structural remodeling such as atrial fibrosis and loss of muscle mass are the most frequent histopathological changes in AF which facilitate initiation and perpetuation of AF. Electrical remodeling occurs, which results in changes in the action potential and contributes to the maintenance of AF. In other words, when structural and electrical changes occur in conjunction with AF, this perpetuates fibrillations. Ultimately AF causes delayed emptying from atria.[5][6] This can increase the risk of stroke.[2] Prolonged AF makes restoration and maintenance of sinus rhythm more difficult.[5]

- AF with associated heart disease: specific cardiovascular conditions associated with AF include valvular heart disease (most often mitral valve disease), heart failure (HF), coronary artery disease, and hypertension, particularly when LV hypertrophy is present. In addition, heart disease leading to thicker ventricular walls (HCM), dilated cardiomyopathy, and congenital heart disease, especially atrial septal defect in adults are associated with AF. Potential etiologies also include restrictive cardiomyopathies (e.g., amyloidosis, hemochromatosis, and endomyocardial fibrosis), cardiac tumours, and constrictive pericarditis. Further, other heart diseases such as mitral valve prolapse with or without mitral regurgitation, calcification of the mitral annulus, cor pulmonale, and idiopathic dilation of the right atrium, have been associated with a high incidence of atrial fibrillation.[3]

- Familial associated AF: familial AF, defined as lone AF running in a family, is more common than previously recognized but should be distinguished from AF secondary to other genetic diseases like familial cardiomyopathies. The likelihood of developing AF is increased among the offspring of parents with AF, suggesting a familial link to AF but the mechanisms associated with transmission are not necessarily electrical, because the relationship has also been seen in patients with a family history of hypertension, diabetes, or heart failure.[3]

- Autonomic Influence in AF: in general, vagally mediated AF occurs at night or after meals, while adrenergically induced AF typically occurs during the daytime. Beta-blockers are initial drug of choice for adrenergic dominated AF.[3]

Characteristics/Clinical Presentation[edit | edit source]

Atrial Fibrillation (AF) symptoms vary on the functional state of the heart, the location of the fibrillation, and may exist without symptoms.[2],6 Individuals are usually aware of the irregular heart action and may report feeling palpitations or sensations of fluttering, skipping and pounding. Other symptoms experienced can be inadequate blood flow which can cause feelings of dizziness, chest pain, fainting, dyspnea, pallor, fatigue, nervousness, and cyanosis. More than six palpitations occurring in a minute or prolonged repeated palpitations should be reported to the physician.[4] Over time, palpitations may disappear as the arrhythmia becomes permanent; it may become asymptomatic. This is common in the elderly. Some patients experience symptoms only during paroxysmal AF, or only intermittently during sustained AF. An initial appearance of AF may be caused by an embolic complication or an exacerbation of heart failure. Most patients complain of palpitations, chest pain, dyspnea, fatigue, lightheadedness, or syncope. Further, frequent urination (Polyuria) may be associated with the release of atrial natriuretic peptide, particularly as episodes of AF begin or terminate.[3]

An irregular pulse should raise the suspicion of AF. Patients may present initially with a transient ischemic attack (TIA) or ischemic stroke. Most patients experience asymptomatic episodes of arrhythmias before being diagnosed. Patients with mitral valve disease and heart failure often have a higher incidence of AF. Intermittent episodes of AF may progress in duration and frequency. Over time many patients may develop sustained AF. For a newly diagnosed patient of AF, reversible causes such as pulmonary embolism, hyperthyroidism, pericarditis and MI should be investigated.[5]

Associated Co-morbidities[edit | edit source]

- Stroke

- Obesity

- Obstructive sleep apnea

- Diabetes

- Congestive Heart Failure

- Mitral valve disease

- Coronary artery disease

- Hypertension associated with left ventricular hypertrophy

- Hypertrophic obstructive cardiomyopathy

- Dilated cardiomyopathy

- Atrial septal defect [3][4][5][6][7]

Medications[edit | edit source]

Rate control (The typical approach to treating Atrial Fibrillation)

- Metoprolol CR/XL(Toprol XL)

- Bisoprolol (Zebeta)

- Atenolol (Tenormin)

- Esmolol (Brevibloc)

- Propranolol (Inderal)

- Carvedilol (Coreg)

Antihypertensive and calcium channel blocker

- Verapamil (Calan)

- Diltiazem (Cardizem)

Antiarrhythmic and blood pressure support

- Digoxin (Lanoxin)

- Antiarrhythmic

- Amiodarone (Cordarone)

- Dronedarone (Multaq)

Rhythm control

Antiarrhythmic

- Amiodarone(Cordarone)

- Flecainide (Tambocor)

- Propafenone(Rythmol)

- Sotalol(Betapace)

Meds such as anticoagulants (commonly used along side these medications due to AF causing stroke) can cause brain hemorrhage. Benefits must be closely monitored.[5]

Diagnostic Tests/Lab Tests/Lab Values[edit | edit source]

- 12 lead EKG

- Presence of low-amplitude fibrillatory waves on ECG without defined P-waves 2. Irregularly irregular ventricular rhythm 3. Fibrillatory waves typically have a rate of > 300 beats per minute 4. Ventricular rate is typically between 100 and 160 beats per minute.

- Holter monitor

- Event recorder

- Blood test

- Stress tests

- Chest X-ray

- LV Hypertrophy

- 6 minute walk test

- Physical Exam: Irregular pulse, irregular jugular venous pulsations, variation in the intensity of first heart sound.[3][9][4][5]

Systemic Involvement[edit | edit source]

High concentrations of CRP in the blood test, which confirm the presence of systemic inflammation are present in people with Atrial Fibrillation (AF).[3]

Changes in an individual's health such as a newly diagnosed complication may have a psychological impact. Patients may experience depression and other psycho-social challenges as a result of changes in their health status, treatment, frequent visits to the physician's office, and fear of the unknown that may accompany a diagnosis of atrial fibrillation.

Medical Management[edit | edit source]

Rate control and rhythm control through medications

- Studies have demonstrated that a rate control strategy, with a target resting heart rate between 80 and 100 beats/minute, is recommended over rhythm control in the vast majority of patients.

- Catheter ablation

- Atrioventricular node ablation

- Surgical maze procedure

- Thromboembolism Prevention[3][4][5]

Physical Therapy Management[edit | edit source]

There is limited research on the effect of traditional physical therapy and Atrial Fibrillation.

There is also conflicting information on the use of exercise to reduce the risk of AF. Since obesity is an important risk factor, management of weight through exercise and education is a crucial, proactive measure that may reduce the incidence of AF. However, there is conflicting evidence in regard to the optimal prescription of exercise.

Differential Diagnosis[edit | edit source]

- Atrial tachycardia

- Atrial flutter with variable AV block

- Frequent atrial ectopies

- Pulmonary Embolism

- Hyperthyroidism

- Pericarditis

- Myocardial Infarction [8][4][6]

Case Reports/ Case Studies[edit | edit source]

1. Hwang KO. Case Study: Acute and Long-term Management of Atrial Fibrillation. MedPage Today. 2015. Available from: MedPage Today.

2. Ezekowitz MD, Aikens TH, Nagarakanti R, Shapiro T. Atrial fibrillation: outpatient presentation and management. Circulation. 2011; 124: 95–99. Available from: American Heart Association.

3. Peake ST, Mehta PA, Dubrey SW. Atrial fibrillation-related cardiomyopathy: a case report. Journal of Medical Case Reports. 2007;1:111. Available from: National Center for Biotechnology Information.

Resources[edit | edit source]

- AFIB matters: Atrial Fibrillation

- American Heart Association: Atrial Fibrillation Resources For Patients & Professionals

- Cleveland Clinic: Advanced Treatment for Atrial Fibrillation

- Mayo Clinic: Atrial Fibrillation

- StopAfib.org: Atrial Fibrillation Resources

References[edit | edit source]

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 Nesheiwat Z, Jagtap M. Rhythm, Atrial Fibrillation (A Fib). InStatPearls [Internet] 2018 Oct 27. StatPearls Publishing. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK526072/ (last accessed 11.1.2020)

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute [Internet]. [Place Unknown]: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services; Atrial Fibrillation. [updated 2014 September 18; cited 2016 April 2]. Available from: http://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/health/health-topics/topics/af

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 3.4 3.5 3.6 3.7 3.8 3.9 Fuster V, Rydén LE, Cannom DS, Crijns HJ, Curtis AB, Ellenbogen KA, et al. ACC/AHA/ESC 2006 Guidelines for the Management of Patients with Atrial Fibrillation: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines and the European Society of Cardiology Committee for Practice Guidelines (Writing Committee to Revise the 2001 Guidelines for the Management of Patients With Atrial Fibrillation): Developed in collaboration with the European Heart Rhythm Association and the Heart Rhythm Society. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2006: 114(7): p. 257-354.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 4.4 4.5 Goodman CC, Snyder TE. Differential Diagnosis for Physical Therapists, Screening for Referral. 5th ed. St. Louis Saunders; 2012. p. 264-266.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 5.3 5.4 5.5 5.6 5.7 Wadke R. Atrial Fibrillation. Disease-a-Month. 2013 March: 59(3): 67-73.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 6.3 Oishi ML, Xing S. Atrial fibrillation: Management strategies in the emergency department. Emerg Med Prac. 2013: 15(2): p. 1-26.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 Gami AS, Hodge DO, Herges RM, Olson EJ, Nykodym J Kara T, Somers VK. Obstructive Sleep Apnea, Obesity, and the Risk of Incident Atrial Fibrillation. J Am Coll Cardiol [Internet]. 2007 Feb [cited 2016 April 9]; 49(5): 565-571. Available from: http://content.onlinejacc.org/article.aspx?articleid=1188673&...#tab1

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 8.2 8.3 Atrial Fibrillation Fact Sheet [Internet]. Center for Disease Control and Prevention; 2013 [updated 2015 August 13; cited 2016 April 5] Available from: http://www.cdc.gov/dhdsp/data_statistics/fact_sheets/fs_atrial_fibrillation.htm

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 Amerena JV, Walters TE, Mirzaee S, Kalman JM. Update on the management of atrial fibrillation. Med J Aust. 2013: 199(9): p. 592-7.