Disorders of Consciousness

Original Editor - Anna Ziemer

Top Contributors - Naomi O'Reilly, Kim Jackson, Lucinda hampton, Uchechukwu Chukwuemeka, Wendy Walker, Tarina van der Stockt, Simisola Ajeyalemi, Nicole Hills, Admin and Tony Lowe

Introduction[edit | edit source]

Some patients following moderate to severe traumatic brain injury will present with profound and prolonged consciousness impairment. Their rehabilitation needs might differ from other patient groups and usually require treatments to enhance consciousness along with other forms of treatment and therapy used in traumatic brain injury neurorehabilitation. Prevention of medical and neurological complications is agreed as the main focus for this group and currently, there is no pharmacological treatment proven to speed up or improve the recovery from disorders of consciousness.

There is no formal register of patients with disorders of consciousness mainly due to the difficulties with diagnostic codes and transient nature of some of the consciousness conditions. Although patients with disorders of consciousness demonstrate damage in various areas of the brain eg cortico-thalamic network activation deficits being common to these patients.

Patients with disorders of consciousness can be treated in various environments from acute through in-patient rehabilitation to community/nursing care facilities. The facilities and treating team should be experienced in looking after patients with disorders of consciousness and utilise a multidisciplinary approach with family and relatives engaged. It is recommended that multisensory stimulation is provided with auditory (normal talking), visual (pictures), tactile-kinaesthetic (movement and touch) and olfactory (familiar scents like perfumes, food) are used alongside nursing care and therapy. Altered consciousness results from moderate to severe traumatic brain injury, relates to changes in a person’s state of consciousness, awareness or responsiveness. Consciousness requires simultaneous wakefulness and awareness and the relationship between them both is different for different types of consciousness disorder:

| Wakefulness | Awareness | |

|---|---|---|

| Coma | - | - |

| Vegetative State | + to ++ | - |

| Minimally Conscious State | + to ++ | + |

| Emerged from Minimally Conscious State | ++ | ++ |

Unconsciousness Conditions[edit | edit source]

Unconsciousness conditions include:

1. Coma[edit | edit source]

A person in a coma is not aroused, unaware of self and environment and unable to respond to any stimulus. This results from widespread damage to all parts of the brain. The person with TBI may emerge from a coma or enter a vegetative state at various times after the trauma.

2. Vegetative State[edit | edit source]

A person in a vegetative state will demonstrate basic wakefulness with some degree of their sleep-wake cycle restored, but there is no awareness. The person is unaware of their surroundings but may open their eyes, make sounds, respond to reflexes and/or move. Some facial expressions may be observed without apparent cause. Demonstrated behaviour might include: posturing in response to pain, vocalisation, reflexive movement patterns, startle to visual stimuli. The person can remain in a vegetative state permanently, but some patients can make a transition to a minimally conscious state. The speed of transition and degree of emerging from a coma or vegetative state depends on the extent of the brain damage. About 50% of people with TBI in a vegetative state one month since the trauma will recover consciousness however, various degrees of residual physical and cognitive deficits are often present.

A person in coma require complex care and some of the needs might include:

- Postural management programme preventing deformities, contractures and pressure sores including muscle tone management through positioning, splinting, mobilising, sitting in alternative seating systems

- Bladder and bowel management

- Respiratory care including secretion management, eg suctioning, tracheostomy management

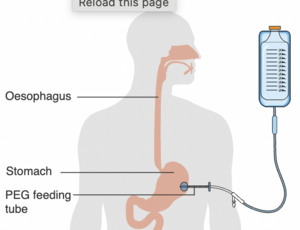

- Percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy (PEG) Feeding

- Management of infections like urinary tract infection, chest infection

- Management or prevention of medical and neurological complications like seizures.

Conscious Conditions[edit | edit source]

Minimally Conscious State[edit | edit source]

A condition of severely altered consciousness but with some signs of self-awareness or awareness of an environment. The awareness can be fluctuating in the degree and consistency but is reproducible. Different forms of minimally conscious state have been defined:

- Minimally conscious state minus characterised by no linguistically mediated behaviour presence, i.e. visual pursuit.

- Minimally conscious state plus characterised by linguistically mediated behaviour like command following, verbalisation.

- Emerged from minimally conscious state return to functional object use and functional communication. [1]

Behaviours specific to minimally conscious state include: localisation to pain stimuli, non-reflexive movement patterns, fixation and pursuit for visual stimuli, intelligible verbalisation, inconsistently following commands, unreliable yes/no responses and some inconsistent object manipulation. The minimally conscious state is sometimes an intermittent state between coma or vegetative state and full consciousness.

Whilst emerging from minimally conscious state people experience confusions which will present as disorientation, attention and memory deficits, restlessness, fluctuating responsiveness, drowsiness, possible delusions. Usually the shorter the confusion state the better the recovery. [2]

Different States of Consciousness also include:

1. Locked-in syndrome[edit | edit source]

Locked-in syndrome usually results from brainstem pathology which disrupts the voluntary control of movement without abolishing either wakefulness or awareness (RCP Guideline 2013). Patients who are ‘locked-in’ are profoundly paralysed but conscious. They can use various forms of communication like simple facial expression, eyes or eyelids movements, computerised eye gaze systems after their clinical status has been established. However, the diagnosis can be prolonged thus very frustrating for the patient. With medical advances, a person living with Locked-in syndrome has an extensive life expectancy and is able to control their environment and access technology for word processing, voice synthesis and to use the internet.

The personal experience of Locked-in syndrome was described by Journalist, Jean-Dominique Bauby, in his book “The Diving Bell and the Butterfly”, which was also successfully filmed.

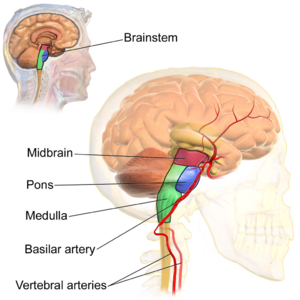

2. Brainstem Death[edit | edit source]

Brainstem death is declared when there is no measurable activity in the brain and the brainstem. During strict testing routine following findings will confirm brain death: coma, lack of brain stem reflexes, apnoea. In a person who has been declared brain dead, the removal of breathing devices will result in cessation of breathing and eventual heart failure. Brain death is considered irreversible and can be declared by 2 senior doctors completing the test twice. Only if all the tests at both times provide a negative outcome the brain death can be certified. The process is followed by certain steps allowing the liaison with relatives and further steps of removing the mechanical ventilation or engaging transplant teams clearly described in national clinical guidelines.

Assessment of Consciousness[edit | edit source]

Assessment of consciousness has an important role in the rehabilitation of people with Disorders of Consciousness following brain injury. According to Schnakers et al [3] approximately 40% of people certified as persistent vegetative state demonstrated some degree of consciousness and 10%of patients certified as a minimally conscious state had actually emerged from it. The misdiagnosis relates to:

- Lack of knowledge and understanding the distinctive features of vegetative state and minimally conscious state

- Relaying on neurological bedside assessment and underestimation of the importance of neurobehavioural outcome measures

- Lack of serial evaluation over time

- Coexisting complex impairment masking certain behaviour like vision or hearing impairment

- Pharmacological agents suppressing consciousness like sedating medication.

Misdiagnosis has wide consequences for long term recovery as might restrict access to neurorehabilitation and limit access to communication strategy development, treatment access and impact on withdrawal of care.

The gold standards for consciousness assessment are behavioural assessment tools. The vegetative state spectrum patients might benefit from functional neuroimaging testing based on yes / no responses using different brain centre activation patterns. [4] It must be noted that in both circumstances negative findings have been noted, which means some patients were diagnosed with a minimally conscious state but actually demonstrated no consciousness.

Coma Recovery Scale - Revised[edit | edit source]

Coma Recovery Scale - Revised is a tool to differentiate between vegetative state and minimally conscious state. Developed by Giacino et al [5] to assess those emerging from a minimally conscious state. Available in many languages including English, Chinese, and French. Constructed with subscales similar to Glasgow Coma Scale, but with much more thorough and detailed itemisation. The score ranges from 0 to 23 allowing greater attention to detail, however, it makes the scale more complicated with a need for increased assessment time, which may be a disadvantage in the Intensive Care Unit.

Sensory Modality Assessment and Rehabilitation Technique[edit | edit source]

The Sensory Modality Assessment and Rehabilitation Technique (SMART) originated from the Royal Hospital for Neuro-disability London. It is a tool recommended by the Royal College of Physicians National Guideline and is used to assess and rehabilitate people with Prolonged Disorders of Consciousness due to severe brain injury.

The SMART assessment and treatment can be used by accredited therapists, doctors or nurses who undergo structured training as well as relatives. The format of the assessment is systemised and includes ten observational sessions over 3 week period and followed by an 8-week treatment.

Observation of activity demonstrated to no stimuli for 10 minutes prior the assessment session and eight modalities stimuli in a couple of carefully organised environment setups including therapy session and leisure activities like watching TV aims to establish any residual awareness in people with vegetative state or to establish residual communication, sensorimotor responses and function potential of a patient with a minimally conscious state. Careful observation of meaningful responses establishes the individual's degree of awareness. There are several potential levels of responses to stimuli:

- No response at all

- Responses occurring at reflex level (non-purposeful, spontaneous response over which the patient has no control)

- Withdrawal (turning or pulling away from a stimulus)

- Localising (finding the stimuli and focusing on it)

- Ability to differentiate between two different stimuli.

A consistent response on 5 consecutive assessment at level 5 following any type of stimuli demonstrates a meaningful response pointing to minimally conscious state or higher level of function. If the minimally conscious state is certified the person assessed using SMART can undergo SMART rehabilitation enhancing communication effectiveness and reproducibility of the responses.

Wessex Head Injury Matrix[edit | edit source]

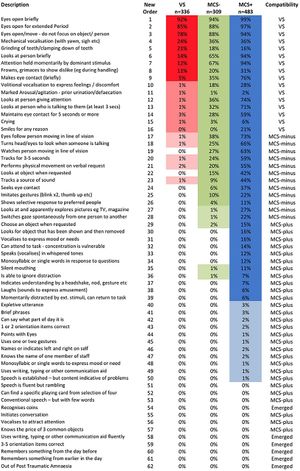

The Wessex Head Injury Matrix (WHIM) is an observational assessment which was developed by Shiel and colleagues to observe patients emerging from coma through post-traumatic amnesia, monitoring subtle minimally conscious state responses and reflect the performance in everyday life. Initially observed 145 behaviours following the recording of basic responses during longitudinal studies of large cohorts were systemised into 6 subscales and contain 62 items. The subscales are as follows:

- Communication

- Attention

- Social behaviour

- Concentration

- Visual awareness

- Cognitio

The items are systemised in a hierarchical order of statistically appearing behaviour. The Wessex Head Injury Matrix score represents the rank of the most advanced item observed. The Wessex Head Injury Matrix demonstrated good to very good reliability and superiority to the Glasgow Coma Scale and GLS in recording subtle changes between vegetative state and minimally conscious state with particularly high sensitiveness of change in patients in a minimally conscious state. The pattern of recovery proposed by Wessex Head Injury Matrix lacks precision and further studies are required to strengthen the sequence of recovery validity.

Glasgow Coma Scale[edit | edit source]

The Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS) is a point scale used to assess a patient's level of consciousness and neurological functioning after brain injury. The scoring is based on best eye-opening response (1 - 4 points), best motor response (1 - 6 Points) and best verbal response (1 - 5 Points) with cut the off-point for coma at 8 points. For more in-depth information see GCS Student’s Guide.

Disorder of Consciousness Scale[edit | edit source]

The Disorder of Consciousness Scale (DoCS-25) is a structured evaluation tool assessing subtle changes in neurobehavioural functioning during consciousness recovery after Traumatic Brain Injury. 25 items describe the behaviour in response to auditory, somatosensory, visual and olfactory stimuli. Raw scores from 0 to 50 are assigned to logits and rescaled on a 0 to 100-point scale.

Rehabilitation of Individuals with Disorders of Consciousness [edit | edit source]

The unique components of rehabilitation of patients with Disorders of Consciousness are:

1. Assessment of level of consciousness and residual voluntary mobility

2. Providing treatment enhancing the level of consciousness

The interventions should address the reversible causes of impaired consciousness. Eapen and colleagues (2018) suggest areas to explored before specialist management of Disorders of Consciousness to be addressed:

- Undermobilisation / Understimulation

- Disrupted Sleep-Wake Cycle

- Pharmacological Sedation

- Co-existing Medical Conditions like infection, metabolic abnormalities

- Neuroendocrine Abnormalities

- Intracranial Abnormalities

- Seizures

Another group of intervention include treatment directly modulating and enhancing awareness. Those treatments include; general neurorehabilitation containing multimodal interventions ie. sensory stimulation, mobilisation like handling, FES Cycling, postural management with positions changes, sitting out of bed, verticalization through tilt table or bodyweight support, Interpersonal interaction especially relatives).

There is strong evidence that verticalization increases brain activation [7] as well as environmental enrichment. [8]

- Pharmacological agents use. Some promising effect has been demonstrated in the use of neurostimulants engaging catecholaminergic pathways like amantadine, levodopa, amphetamine and GABA Agonist like zolpidem;

- Energy Modalities including deep brain stimulation, transcranial magnetic stimulation, vagus nerve stimulation, low intensity focused ultrasound;

- Biological Therapies like stem cell therapy.

All of those interventions aim to activate undamaged but suppressed networks responsible for consciousness and allow the clinicians to believe that in case of network intact and optimal stimulation provided in some cases patients can be moved from vegetative state to minimally conscious state or emerge from the minimally conscious state.

3. Addressing Request limiting the Medical Treatment, Relatives Education and Support, Long-term Placement Planning.

Consideration must be given to neurorehabilitation programmes versus the end of life palliative care. The quality of life issue relates to timely and precise diagnosis of vegetative state or minimally conscious state and availability of specialist rehabilitation and care facilities. The patients placed in generic placements demonstrate a higher rate of complications and poorer consciousness recover. It must be recognised that medical stability is a prerequisite for full access to neurotherapeutic treatment, therefore the placement needs to be timed accordingly to ensure full use of offered neurorehabilitation.

The families of patients with disorders of consciousness require special attention due to their needs related to the difficulty of decisions they need to make immediately after their relative's traumatic brain injury. They may need to make decisions about the termination of treatment or organ donation. Relatives also often struggle with their family member's experience during prolonged disorders of consciousness. The difficult nature of consciousness and complicated procedures accompanied the care and rehabilitation of people with disorders of consciousness are other stressful factors. For example, a non-medically trained person may find it difficult to understand that a person who can open their eyes, make noises or reflexive movements yet still be unconscious. Therefore, support and education are crucial for positive inclusion of relatives and friends in the multidisciplinary team.

Families provide invaluable information and extend “the observation time” often spending time with the person with disorders of consciousness when clinical staff is not present, i.e. in the evenings. [1] They also might recognise subtle changes and provide more powerful stimuli than medical staff enhancing the behavioural response of the person with disorders of consciousness.

Special consideration of training must be given to families who do wish their relatives to be discharged home. The rehabilitation of patients with disorders of consciousness also shares general features of rehabilitation of a patient with severe traumatic brain injury:

4. Bodily Functions Management: skin integrity, respiratory, nutrition, bladder and bowel care

5. Managing Medical and Neurological Complications

which usually are consistent with general traumatic brain injury complications however often more severe

6. Managing Neuromusculoskeletal Problems

Patients with disorders of consciousness often present with: weakness, spasticity, contractures, heterotopic ossification, peripheral nerve damage, critical illness polyneuropathy. This area of intervention has an enormous impact on general neurorehabilitation as often motor response is assessed during consciousness examinations, which then impact the pathway of care. The musculoskeletal health allows more efficient pain management, positioning and mobilisation and determines the degree of voluntary movement in the future.

7. Establishing Communication when appropriate

8. Providing Optimal Level Care

To prevent the complications of immobilisation like pressure sores or provide treatment for existing medical problems like neuro infection.

9. Pain Management

Patients in the minimally conscious state are capable of feeling pain and with multiple sources of pain (e.g., muscle tone changes, infections, cannulation, etc.) analgesic treatment is appropriate, however, consideration must be given to the sedative nature of those pharmacological agents during consciousness assessment.

Clinical Outcomes in Disorders of Consciousness[edit | edit source]

The outcome can be measured by mortality, consciousness recovery or functional recovery and is directly related to diagnosis and with better prognosis of patients in Minimally Conscious State than Vegetative State. Patients with traumatic brain injury have a better prognosis than those with nontraumatic. The time of Disorders of Consciousness also is a prognostic factor with patients being longer in Vegetative State having worse chances to recover the consciousness. According to Eapen et al [1] 52% patients certified with Vegetative State at 1 month can recover consciousness, 35% of patients with Vegetative State at 3 months, 16% of patients with Vegetative State at 6 months and nearly no chance when Vegetative State still certified at 12 months.

The functional recovery is also determined by time of Disorders of Consciousness and often this group of patients demonstrates moderate to severe impairment in different proportions. However, due to medical care and therapeutic advances, the chance of functional recovery is now much greater than even 20 years ago, therefore, this group of patients should receive structured neurorehabilitation programmes to higher their chances of recovery including inpatient and community-based rehabilitation. There is no prognostication tool of clear reliability when quantifying the potential of recovering from Disorders of Consciousness, however, some techniques becoming more useful like functional imaging or cognitive testing.

The Ethical Issues[edit | edit source]

There are many factors to be considered when looking after patients with Disorders of Consciousness:

- Diagnostic and prognostic uncertainty related to decision making should treatment withdrawal considered

- Use of new assessment and treatments methods

- Research participation

- Limitation/withdrawal of medical treatment in a patient with a persistent vegetative state.

At this point in time, there is an ethical and legal consensus that patients in a chronic vegetative state can have the treatment withdrawn and no agreement for those in a minimally conscious state.

Resources[edit | edit source]

References[edit | edit source]

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 Eapen BC, Cifu DX. Editor. Rehabilitation After Traumatic Brain Injury. Elsevier, 2018

- ↑ Sherer M, Vaccaro M, Whyte J, Giacino J.T and the Consciousness Consortium. Facts about the Vegetative and Minimally Conscious States after Severe Brain Injury 2007. The Consciousness Consortium 2018 by University of Washington/MSKTC. Available from: https://www.brainline.org/article/facts-about-vegetative-and-minimally-conscious-states-after-severe-brain-injury (accessed 15 September 2019)

- ↑ Schnakers C, Vanhaudenhuyse A, Giacino J, Ventura M, Boly M, Steve Majerus S, et al. Diagnostic accuracy of the vegetative and minimally conscious state: Clinical consensus versus standardized neurobehavioral assessment. BMC Neurology. 2009; 9:35. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2377-9-35

- ↑ Monti MM, Vanhaudenhuyse A, Coleman MR, Boly M, Pickard JD, Tshibanda L, et al.Willful Modulation of Brain Activity in Disorders of Consciousness. New England Journal of Medicine. 2010; 362:579-589. DOI: 10.1056/NEJMoa0905370

- ↑ Giacino JT, Kalmar K, Whyte J. The JFK Coma Recovery Scale-Revised: measurement characteristics and diagnostic utility. Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation. 2004;85(12):2020-9.

- ↑ Turner-Stokes L, Bassett P, Rose H, Ashford S, Thu A. Serial measurement of Wessex Head Injury Matrix in the diagnosis of patients in vegetative and minimally conscious states: a cohort analysis. BMJ open. 2015 Apr 1;5(4):e006051.

- ↑ Krewer C, Luther M, Koenig E, Müller F. Tilt Table Therapies for Patients with Severe Disorders of Consciousness: A Randomized, Controlled Trial. PLos One. 2015;10(12):e0143180. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0143180

- ↑ Abbasi M, Mohhamadi E, Sheaykh Rezayi A. Effect of a regular family visiting programme as an affective, auditory, and tactile stimulation on the consciousness level of comatose patients with a head injury. Japan Journal of Nursing Science. 2009;6(1):21-26.

- ↑ Craig Hospital. Disorder of Consciousness & Cognitive Recovery Following TBI Levels 1-5. Available from: https://youtu.be/ShrBojM0gTA[last accessed 30/08/19]

- ↑ Craig Hospital. Disorder of Consciousness & Cognitive Recovery Following TBI Levels 4-6. Available from: https://youtu.be/cFujZtHtzjw[last accessed 30/08/19]

- ↑ Craig Hospital. Disorder of Consciousness & Cognitive Recovery Following TBI Levels 7-10.Available from: https://youtu.be/tGbZVbcp81k[last accessed 30/08/19]