Assessment of Foot Neuropathies

Top Contributors - Stacy Schiurring, Jess Bell and Kim Jackson

Neuropathy Assessment[edit | edit source]

Diabetes is the leading cause of peripheral neuropathy worldwide.[1] Peripheral neuropathy can have devastating outcomes, including (1) foot ulcers, (2) major amputation, (3) falls, (4) intracranial injuries, and (5) decreased quality of life. Approximately one in four people with diabetes will develop a diabetic foot ulcer.[2]

Neuropathy, foot deformity, and trauma are the most common "triad of causes that interact and ultimately result in ulceration".[1] Proper assessment and identification of patients at risk for ulcer formation is vital in wound prevention and complication management.[1] This article provides an overview of a systematic method of foot neuropathy assessment. It also details foot self-care and prevention education.

For a review of foot neuropathy types, please see this article. Please see this article for a list of common wound care terminology.

Frequency of Assessment[edit | edit source]

The American Diabetes Association (ADA) Standards of Medical Care in Diabetes recommends all patients with diabetes be assessed for diabetic peripheral neuropathy:

- at the time of diagnosis of type 2 diabetes mellitus

- five years after the diagnosis of type 1 diabetes mellitus

- and then at least annually for continued reassessment[3][4]

However, depending on a patient's risk for foot ulcer formation, they may need to be reassessed more frequently.[4] The International Working Group on the Diabetic Foot (IWGDF) developed an evidence-based risk stratification system which provides recommendations on how often more at-risk patients with diabetes should be reassessed. The assignment of risk is based on the presence of:[5]

- lack of protective sensation (LOPS)

- peripheral artery disease (PAD)

- foot deformity

- other high-risk diagnoses or procedures (see Table 1 for details)

| Risk Category | Risk of Ulcer Formation | Characteristics | Reassessment Frequency |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | Very low |

|

Once a year |

| 1 | Low | LOPS or PAD | Once every 6-12 months |

| 2 | Moderate |

|

Once every 3-6 months |

| 3 | High | LOPS or PAD and one or more of the following:

|

Once every 1-3 months |

The above table is adapted from information provided in the IWGDF 2023 update.[5]

Neuropathy Assessment Guidelines[edit | edit source]

The use of assessment guidelines or checklists is recommended to gather consistent objective assessments, especially when following a patient over multiple visits and across time.

Benefits of an assessment checklist include:[4]

- ability to establish trends and identify changes over time to guide inventions

- facilitates communication among caregivers by providing objective and straight-forward information with consistent terminology

- clearly identify risks for developing foot ulcers so that they can be addressed and monitored

- creates an opportunity to provide risk reduction education unique to the needs of the patient

Identifying an At-Risk Foot[edit | edit source]

Any person with diabetes is considered to have an "at-risk foot" or "diabetic foot disease" if they present with the risk of developing foot ulceration and or infection.[6] Signs that a person with diabetes is at risk of foot ulceration include (1) LOPS, and (2) diagnosis of PAD.[5] By assessing for changes in LOPS, a rehabilitation or wound care professional can screen for changes in a patient's risk for the development of diabetic foot ulcers. Prevention of a foot ulcer is more efficient clinically and financially than foot ulcer treatment and closure. Please see the section below on Foot Ulcer Prevention for more information.

Patients at very low risk for foot ulceration (IWGDF risk 0, please see Table 1) should be screened at least annually.[5][4]

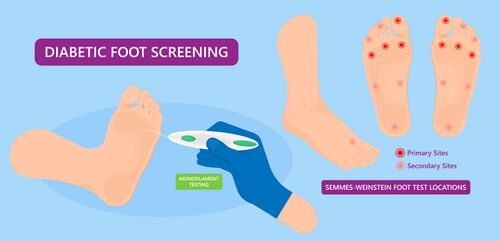

Annual Foot Screening:[5]

- Assess for presence of new or recurrent foot ulcer

- Assess for LOPS using one of the following methods:

- Pressure perception: Semmes-Weinstein 5.07[4] or 10-gram monofilament[4][5]

- Vibration perception: 128-Hz tuning fork[4]

- If monofilament or tuning fork are not available, test tactile sensation: lightly touch the tips of the patient's toes with the tip of the clinician's index finger for 1–2 seconds[5]

- Current vascular status: history of intermittent claudication, palpation of pedal pulses

The following optional video demonstrates a monofilament assessment of the foot.

The following optional video demonstrates a tuning fork assessment of the foot.

Comprehensive Examination Guidelines/Checklist[edit | edit source]

If a patient has either LOPS and/or PAD, they are at risk of ulceration (IWGDF risk 1-3, please see Table 1), and a more comprehensive examination is indicated.[5]

Detailed Medical and Social History[edit | edit source]

The following table lists foot-specific medical history questions recommended by the IWGDF. As always, use clinical judgment and explore other topics as warranted.

| Area of Questioning | Clinical Reasoning |

|---|---|

| Previous ulceration[4][5] | The recurrence rate for diabetic foot ulcers is high, and areas of previous ulceration need to be protected and monitored for potential re-ulceration. Patient and caregiver education is vital to maintain skin integrity - please see the education section below for more details. |

| Previous amputation (minor or major)[4][5] | Lower limb amputation causes biomechanics changes in the remaining limb and alters the patient's gait pattern. Ulceration risk will shift to other areas of the remaining limb due to changes in pressure during weight-bearing and gait. |

| ESRD[4][5] | Patients with ESRD and diabetes mellitus have a significant increase in the frequency of diabetic foot ulcers, experiencing foot complications at more than twice the frequency and a rate of amputation 6.5-10 times higher than patients with diabetes alone.[9] |

| Prior foot inspection education[4][5] | It is important to assess a patient's education and training carry-over from previous education sessions and identify any areas where additional education is needed. |

| Foot pain (at rest or with activity) or numbness[5] | Changes in sensation (pain, burning, tingling, numbness, etc) in the feet is the most common symptom of diabetic neuropathy. A common presentation of this pain is to be worse at rest and improve with activity. |

| Mobility[4][5] | This should include functional mobility, gait assessment, balance assessment, durable medical equipment (DME) recommendations, and fall risk screening. Neuropathy can affect a patient's ability to efficiently and safely complete necessary mobility and increase their fall risk. Changes in gait dynamics can put the patient at risk of developing new foot wounds due to changing pressures over their feet. |

| Social History | |

| Other suggested interview topics | |

| Claudication[4] | Claudication presents as cramping, fatigue, or pain in the calf, thigh, or buttock after a set amount of time performing a physical activity such as walking. The pain is improved with rest and lower limb elevation. Claudication is a symptom of arterial insufficiency and can be the first indication of significant arterial obstruction to the lower limb.[10] |

| Medication[4] | Screen for medications or polypharmacy, which could affect balance. Please see the Resources section for more information and optional recommended reading on this topic. |

The above table is adapted from information provided in the IWGDF 2023 update[5] and Diane Merwarth PT.[4]

To learn more about performing a fall risk screening/falls assessment, please see this optional additional article.

Vascular Status[edit | edit source]

Although ischaemia is not considered a major cause of neuropathic wounds in a diabetic foot, it has been found to be a complication in over 65% of all individuals who develop a diabetic foot ulcer. Wound care professionals should refer patients back to their referring doctor for a more invasive vascular workup if they suspect arterial compromise.[4]

| Assessment | Procedure | Clinical Reasoning |

|---|---|---|

| Pedal pulses[4][5] | Assess all pulses of the lower limb (femoral, popliteal, dorsalis pedis, posterior tibialis) for a true clinical picture of vascular status:

|

|

| Capillary refill[4][5] | Capillary refill test | Tests the integrity of the patient's arterial flow, which has an effect on wound healing potential. |

| Skin temperature[4] |

|

|

| Ankle pressure and Ankle-Brachial Index (ABI) OR | Measures the ratio between the systolic blood pressure of the lower limb and the upper limb to assess for narrowing or blockages in the arteries in the legs. | The ABI is not considered reliable in patients with chronic diabetes due to arterial wall stiffening. Instead, it is recommended that the toe-brachial index is completed if available. |

The above table is adapted from information provided in the IWGDF 2023 update[5] and Diane Merwarth PT.[4]

Skin Assessment[edit | edit source]

It is important to assess and compare both feet.

| Assessment | Clinical Reasoning |

|---|---|

| Colour[4][5] | Autonomic changes related to peripheral neuropathy can result in changes in skin colour. |

| Temperature[5] | Please see Table 3 for details |

| Callus[4][5] | A callus is a sign of abnormal pressures during gait. It must be removed as the callus itself can also act as a source of pressure. Removing the callus also enables the healthcare professional to visualise viable skin for proper assessment. Wounds can form under a callus and cannot be assessed or treated until the callus is removed. |

| Oedema[5] | Autonomic changes related to peripheral neuropathy can result in distal extremity and foot swelling and oedema. |

| Pre-ulcerative signs[4][5] | Pre-ulcerative signs are related to autonomic neuropathy. Signs can include: |

| Other suggested skin assessment areas | |

| Web spaces[4] | Wounds can "hide" in these areas. |

| Plantarflexor creases at the base of the toes[4] | Wounds can also be difficult to visualise in these areas, especially if a patient has foot deformities. Can also be at risk of mechanical injury if the patient has impaired sensation secondary to neuropathy. |

The above table is adapted from information provided in the IWGDF 2023 update[5] and Diane Merwarth PT.[4]

Bone/Joint Assessment[edit | edit source]

Assess the patient while they are lying down and in standing, and compare bilaterally.

| Assessment | Clinical Reasoning |

|---|---|

| Deformities[4] | Foot deformities put patients at a greater risk for developing wounds due to abnormal pressures during weight bearing and gait. They also make it difficult for patients to find properly fitting shoes. Deformities can include:[4]

|

| Excessive bony prominences[4] | Abnormally large bony prominences can act as sources of internal pressure. Examples include:

|

| Decreased joint mobility | Tendons can stiffen due to chemical and cellular changes related to diabetes. This results in a decrease in foot and ankle range of motion. Decreased foot mobility will alter a patient's gait pattern, increase plantar pressures, decrease shock absorption ability, and increase the risk of ulceration. Primary areas of concern:

|

The above table is adapted from information provided in the IWGDF 2023 update[5] and Diane Merwarth PT.[4]

Sensation Assessment[edit | edit source]

| Assessment | Procedure | Clinical Reasoning |

|---|---|---|

| Reassess LOPS[4] | For more information on this, please see the Annual Foot Screening box under the Identifying an At-Risk Foot heading. | Reassess for LOPS if previously noted to be present |

| Proprioception[4] | There is limited consensus in the literature on how to test proprioception. Options include:

|

Proprioceptive sense is vital for proper balance, gait dynamics and sequencing, and fall prevention. |

The above table is adapted from information provided by Diane Merwarth PT.[4]

Mental Health and Cognitive Disorders[edit | edit source]

| Assessment | Clinical Reasoning |

|---|---|

| Dementia[4] | A patient might present with dementia-related gait abnormalities, balance impairments, and fall risk. A dementia diagnosis may also affect the patient's discharge recommendations and need for assistance in the home setting. |

| Depression[4] | A diagnosis of depression can affect balance |

The above table is adapted from information provided in the IWGDF 2023 update[5] and Diane Merwarth PT.[4]

Footwear Assessment[edit | edit source]

Footwear provides protection from potential injury from the patient's environment. Ill-fitting shoes can be a source of pain, increase a patient's fall risk, and be a major factor in diabetic foot ulcer formation. A footwear assessment is an important part of the clinical assessment because it serves a preventative role in wound formation and can improve overall foot health.[12]

| Assessment | Clinical Reasoning |

|---|---|

| Ill-fitting[4][5] | |

| Inadequate[4][5] | Damaged or broken shoes can increase fall risk and cause similar issues to skin integrity as ill-fitting shoes. Improper fastening due to missing laces or non-functioning velcro can also lead to similar issues.[4] |

| Lacking[4][5] | Patient's feet are not protected from environmental hazards, which puts them at significant risk for injury and wound formation.[4] |

The above table is adapted from information provided in the IWGDF 2023 update[5] and Diane Merwarth PT.[4]

Foot Care Assessment[edit | edit source]

Assessing a patient's ability to complete their foot self-care is vital to maintaining foot health and wound prevention. This part of the foot assessment evaluates the patient's ability to reach, inspect, and care for their feet and nails. The assessing rehabilitation professional should note any physical limitations a patient presents with, which could limit their ability to perform foot self-care.

Physical limitations to self foot care include:[4][5]

- vision

- obesity

- decreased flexibility

| Assessment | Clinical Reasoning |

|---|---|

| Toenail condition[4][5] | Patients with diabetes can present with thick, rough nails due to disease-associated changes in the keratin and vascular changes:

|

| State of cleanliness of feet and socks[4][5] | A patient's physical limitations (such as reduced vision, obesity, limited range of motion) may hinder their ability to adequately complete self-care and hygiene.[5] Unclean feet and socks, especially moist socks, can provide an environment for unwanted bacterial growth and cause skin maceration. |

| Superficial fungal infection[4][5] | Superficial fungal infection is a consequence of maintaining a moist environment, such as damp socks and shoes, over the foot. Fungal infections are common in patients with diabetic foot ulcers and can lead to non-healing wounds. The early detection and treatment of fungal infection can improve patient wound healing and avoid amputations.[13] |

The above table is adapted from information provided in the IWGDF 2023 update[5] and Diane Merwarth PT.[4]

Special Topic: Toenail Care[edit | edit source]

Toenail care can be challenging for patients with diabetes. The disease can cause nails to thicken and make trimming difficult without specialised tools. In addition, physical limitations such as decreased vision, limited mobility, and difficulty accessing their feet can prevent patients from managing their own nail care. As a result, the toenails of patients with diabetes can grow to a length and girth, which puts pressure on the surrounding tissues and increases the risk of wound formation.[14]

Risks of improper diabetic nail care: bacterial or fungal infection of the nails or in the surrounding soft tissue.[15]

Who can perform nail care: only skilled and properly trained medical and rehabilitation professionals should trim the toenails of a patient with diabetes.[4] The patient should not trim their own toenails. Family members/caregivers also should not perform nail care unless they have been specifically trained and determined to be competent.

Nail shape matters: trim toenails straight across and gently smooth any sharp edges with a nail file.

Patient Education/Caregiver Training[edit | edit source]

- Foot Care Knowledge. Patient and caregiver knowledge and ongoing education are vital in reducing the risk of developing a diabetic foot ulcer. Providing patients with educational handouts and flyers has been found to improve education retention and decrease appointment "no-show" rates.[16]

Topics of patient and caregiver education and training should include:[17]

- daily inspection of the feet and between the toes

- daily foot hygiene

- avoid barefoot walking both indoors and outdoors

- wearing well-fitting, appropriate footwear

- who can and should trim the patient's toenails

- proper diet

- blood sugar monitoring

- exercise

- smoking cessation

- Foot Ulcer Prevention Education

According to the IWGDF Prevention Guideline, there are five key elements to foot ulcer formation prevention:[5]

- identify the person with an at-risk foot

- regularly inspect and examine the feet of a person at risk for foot ulceration

- provide structured education for patients, their family and healthcare professionals

- encourage routine wearing of appropriate footwear

- treat risk factors for ulceration

Resources[edit | edit source]

Clinical Resources[edit | edit source]

Medication Review Resources:

- Medications Linked to Falls Guideline for patients 65yo+ (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention)

- Medications with Fall Risk Precautions (Texas Health and Human Services)

- Spampinato SF, Caruso GI, De Pasquale R, Sortino MA, Merlo S. The treatment of impaired wound healing in diabetes: looking among old drugs. Pharmaceuticals. 2020 Apr 1;13(4):60.

Clinical Assessments:

- Sharpened Rhomberg

- Sensation testing monofilament form

- Infographic tips for health feet (printable, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention)

Please view this optional 5-minute video for a demonstration of a foot neuropathy assessment.

References[edit | edit source]

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 Boulton AJ, Armstrong DG, Albert SF, Frykberg RG, Hellman R, Kirkman MS, Lavery LA, LeMaster JW, Mills Sr JL, Mueller MJ, Sheehan P. Comprehensive foot examination and risk assessment: a report of the task force of the foot care interest group of the American Diabetes Association, with endorsement by the American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists. Diabetes care. 2008 Aug 1;31(8):1679-85.

- ↑ Hicks CW, Wang D, Windham BG, Matsushita K, Selvin E. Prevalence of peripheral neuropathy defined by monofilament insensitivity in middle-aged and older adults in two US cohorts. Scientific reports. 2021 Sep 27;11(1):19159.

- ↑ American Diabetes Association Professional Practice Committee; 12. Retinopathy, Neuropathy, and Foot Care: Standards of Medical Care in Diabetes—2022. Diabetes Care 1 January 2022; 45 (Supplement_1): S185–S194.

- ↑ 4.00 4.01 4.02 4.03 4.04 4.05 4.06 4.07 4.08 4.09 4.10 4.11 4.12 4.13 4.14 4.15 4.16 4.17 4.18 4.19 4.20 4.21 4.22 4.23 4.24 4.25 4.26 4.27 4.28 4.29 4.30 4.31 4.32 4.33 4.34 4.35 4.36 4.37 4.38 4.39 4.40 4.41 4.42 4.43 4.44 4.45 4.46 4.47 4.48 4.49 4.50 4.51 4.52 4.53 4.54 Merwarth, D. Understanding the Foot Programme. Assessment of Foot Neuropathies. Physioplus. 2023.

- ↑ 5.00 5.01 5.02 5.03 5.04 5.05 5.06 5.07 5.08 5.09 5.10 5.11 5.12 5.13 5.14 5.15 5.16 5.17 5.18 5.19 5.20 5.21 5.22 5.23 5.24 5.25 5.26 5.27 5.28 5.29 5.30 5.31 5.32 5.33 5.34 5.35 5.36 5.37 5.38 5.39 5.40 Schaper NC, van Netten JJ, Apelqvist J, Bus SA, Fitridge R, Game F, Monteiro‐Soares M, Senneville E, IWGDF Editorial Board. Practical guidelines on the prevention and management of diabetes‐related foot disease (IWGDF 2023 update). Diabetes/Metabolism Research and Reviews. 2023 May 27:e3657.

- ↑ Craus S, Mula A, Coppini DV. The foot in diabetes–a reminder of an ever-present risk. Clinical Medicine. 2023 May 17.

- ↑ YouTube. Monofilament Assessment of the Foot - OSCE Guide | Geeky Medics. Available from: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=aQHDIkNSyxk [last accessed 01/September/2023]

- ↑ YouTube. Neurologic Examination of the Foot: The 128 Hz Tuning Fork Test | 360 Wound Care. Available from: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=X3kW26L_7dA [last accessed 01/September/2023]

- ↑ Papanas N, Liakopoulos V, Maltezos E, Stefanidis I. The diabetic foot in end stage renal disease. Renal failure. 2007 Jan 1;29(5):519-28.

- ↑ Smith RB III. Claudication. In: Walker HK, Hall WD, Hurst JW, editors. Clinical Methods: The History, Physical, and Laboratory Examinations. 3rd edition. Boston: Butterworths; 1990. Chapter 13. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK235/

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 11.2 Packer CF, Ali SA, Manna B. Diabetic ulcer. 2023.

- ↑ Ellis S, Branthwaite H, Chockalingam N. Evaluation and optimisation of a footwear assessment tool for use within a clinical environment. Journal of Foot and Ankle Research. 2022 Feb 10;15(1):12.

- ↑ Kandregula S, Behura A, Behera CR, Pattnaik D, Mishra A, Panda B, Mohanty S, Kandregula Sr S, BEHERA C. A clinical significance of fungal infections in diabetic foot ulcers. Cureus. 2022 Jul 14;14(7).

- ↑ Beuscher TL. Guidelines for diabetic foot care: A template for the care of all feet. Journal of Wound Ostomy & Continence Nursing. 2019 May 1;46(3):241-5.

- ↑ Hillson R. Nails in diabetes. Practical Diabetes. 2017 Sep;34(7):230-1.

- ↑ Williams O'Braint Z, Stepter CR, Lambert B. Preventive Nail Care Among Diabetic Patients: A Quality Improvement Initiative. Journal of Wound, Ostomy and Continence Nursing. 2022 Nov 1;49(6):559-63.

- ↑ Alsaigh SH, Alzaghran RH, Alahmari DA, Hameed LN, Alfurayh KM, Alaql KB, Alsaigh S, Alzaghran R, ALAHMARI DA, Hameed L, Alfurayh K. Knowledge, Awareness, and Practice Related to Diabetic Foot Ulcer Among Healthcare Workers and Diabetic Patients and Their Relatives in Saudi Arabia: A Cross-Sectional Study. Cureus. 2022 Dec 5;14(12).

- ↑ YouTube. Diabetic Foot Examination - OSCE Guide | Geeky Medics. Available from: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=_BQdeaEHfZc [last accessed 01/September/2023]