Thoracic Disc Syndrome

This article is currently under review and may not be up to date. Please come back soon to see the finished work! (17/04/2020)

Original Editor - Sarah Harnie

Top Contributors - Sarah Harnie, Maarten Wuijts, Arno Vrambout, Lucinda hampton, Kim Jackson, Marleen Moll, Rachael Lowe, Bouzarpour Faryân, Claire Knott, 127.0.0.1, WikiSysop, Abbey Wright, Admin and Evan Thomas

Definition/Description[edit | edit source]

'Thoracic syndrome’ is an umbrella term for all pathological clinical manifestations due to functional (physiopathological) disturbances and degenerative changes of the thoracic motion segments. Essentially, we distinguish three kinds of degenerative diseases of the thoracic spine:

- Benign spondylosis and osteochondrosis in the ventral portion of the thoracic motion segments

- disc prolapse into the epidural space with and without clinical signs of spinal cord compression

- Structural and functional disturbances of the intervertebral and costovertebral joints.

Disc disease in the thoracic spine is far less common than in lumbar and cervical regions, it only accounts for 2% of all cases of disc disease and tends to be less serious than disc disease elsewhere in the spine.

Clinically Relevant Anatomy[edit | edit source]

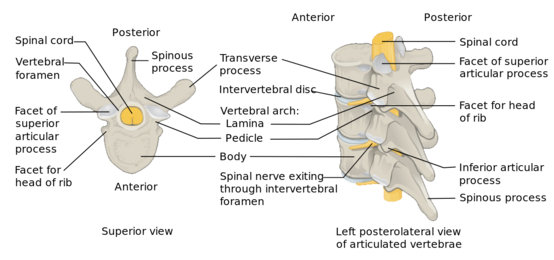

The twelve thoracic discs become broader and higher caudally. In terms of ratio of width to height, they are more flat than the cervical and lumbar discs. The thoracic spinal canal is quite narrow (most so from T4-T9) with a thin epidural space between the spinal cord and surrounding bone or disc.

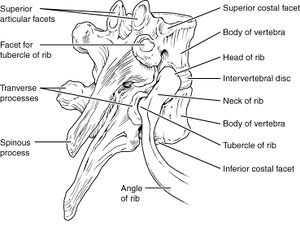

Besides the intervertebral joints, the thoracic spine also contains the costotransverse joints which indent the lower portion of the intervertebral foramina. Because the thoracic foramina are much wider, bony narrowing such as is seen in the cervical spine, is hardly ever seen here.[1]

The thoracic spine is a relatively rigid part of the spine, compared to the cervical and lumbar parts. Its stability is the direct result of the rib cage. Each rib head between T2 and T10 has two facets that articulate with their respective vertebral body and one more cephalic - meaning that the head of the T7 rib articulates with the T6 and T7 bodies. The heads of T1, T11 and T12 ribs only articulate with their similarly numbered vertebral bodies.

Because the facets of the T1-T10 vertebral bodies are oriented vertically (with slight medial angulation in the coronal plane) there is significant stability during flexion and extension, while allowing greater movement in lateral bending and rotation[2]. The active movements the average individual can carry out in the thoracic spine are as follows:

• Forward flexion (20° to 45°)

• Extension (25° to 45°)

• Side flexion, left and right (20° to 40°)

• Rotation, left and right (35° to 50°)

The curvature of the thoracic spine is convex, which places the ventral portion of the motion segments under greater stress with high intradiscal pressure. This is different from the cervical or lumbar spine, where an axial compressive force can be borne by the intervertebral joints and interlaminar soft tissue.[1]

Between each vertebral body lies the intervertebral disc. These are composed of two materials: the outer hard fibrous ring (annulus fibrosis) and an inner soft gelatinous core (nucleus pulposus). The intervertebral discs absorb shock and allow flexibility of the vertebral column. As the body ages, the integrity of the intervertebral disc declines and can cause the inner core of the disc to protrude through the outer layer, leading to possible compression of the nerve roots or the spinal cord - giving rise to radicular or myelopathic symptoms.

Justin G. R. Fletcher et.al concluded that all dimensions (anterior disc height, posterior disc height, anteroposterior disc dimension and transverse disc dimension) of the thoracic disc were greater in men than in women, except the middle disc height. The researchers explain this difference with a scaling effect because the differences in disc and vertebral body heights (6-9%) were proportionally similar to their mean difference in stature (7%). The lower thoracic spine has a larger range of flexion and extension, which is why the disc height is greater in the more caudal discs of the thoracic spine. Anteroposterior and transverse dimensions of the thoracic intervertebral discs increase caudally because these discs need to support a greater compressive load. The greater axial cross-sectional area reduces compressive stress in these discs.

Epidemiology/Etiology[edit | edit source]

Because the thoracic discs and vertebral bodies must carry the entire burden, we find more vertebral compression fractures and protrusions of disc tissue through the vertebral body end plates into the spongiosa. The pressure also leads to premature regressive changes (particularly in the middle and lower thoracic section) and can involve extensive spondylosis and osteochondrosis. However, these changes are usually asymptomatic and only noticed incidentally on radiological studies.

Why clinically significant thoracic disc disease is less common, has essentially two causes:

- As opposed to the cervical or lumbar spine, the intervertebral foramina of the thoracic spine are located at the level of the body, as opposed to directly behind the discs.

- There is relatively little movement in the thoracic motion segments, so the anatomical relationship of neural structures to their surroundings remains constant.[1]

Thoracic disc herniation is rare and asymptomatic in 70% of the cases, making up only 0.5% to 4.5% of all disc ruptures and 0.15%-1.8% of surgically treated herniations.

Most patients (80%) that present with problems are between 30-40 years old. Han & Jang demonstrated a relatively even distribution in prevalence across age groups: higher in male participants (8.0%) than in female participants, and more frequent in patients with lumbar surgical lesions (8.2%) than without surgical lesions.

Thoracic disc lesions are primarily degenerative of nature and affect mostly the lower part of the thoracic spine.[2] Three quarters of incidence occurs below T8, with T11-T12 being most common.[3][4] The exact cause of disc degeneration is believed to be multifactorial, factors that can attribute include:

- Trauma

- Metabolic abnormalities

- Genetic predisposition

- Vascular problems, and

- Infections

As mentioned above, symptomatic thoracic disc degeneration is clinically rare. The role of injury in patients with thoracic disc herniation is unclear, with contradicting numbers in different articles. A history of trauma may be present in younger individuals who develop thoracic pain. Literature describes a few cases of thoracic disc herniation in top athletes, such as professional baseball pitchers.[5]

It is worth noting that in acquired deformities of the spine (such as scoliosis or Scheuermann disease) develop gradually which allow the nerve roots to adapt to the situation thereby not necessarily causing thoracic syndrome.[1]

Characteristics/Clinical Presentation[edit | edit source]

In all thoracic pain, extensive anamnesis is important, particularly in patients with a history of carcinomas. General matters such as weight loss, (chronic) coughing, past trauma, thoracic surgery and infections must also be explored.

Degenerative thoracic syndromes can be classified as local, radicular (intercostal neuralgia) or pseudoradicular. Red flags one should be aware of are:

- Myelopathy

- Gait disturbance

- Paralysis

- Cardiovascular disturbances

- History of: - Trauma - Tumor - Infection - Constitutional symptoms (feeling ill) - Weight loss - Laboratory abnormalities

Initially, the most common thoracic pain occurs in the midline area. This can be unilateral or bilateral pain and is dependent on the location and significance of the herniation.[6] The patient might describe a band-like discomfort in a dermatomal distribution in the case of radicular pain. Axial pain is usually described as mild to moderate in intensity, localised in the middle to lower thoracic region. A radiating component may be present, referred to the middle to lower lumbar spine[2].

In the case of thoracic prolapse, the patient might give a history of axial compression of the trunk (e.g. bending forward and lifting a heavy object). The clinical presentation of symptomatic thoracic disc herniation can vary widely and patients may present with either radicular and/ or myelopathic pain. This depends on if the herniated disc compresses the nerve roots or spinal cord itself. The pain worsens when the patients coughs or increases the intra-abdominal pressure[1].

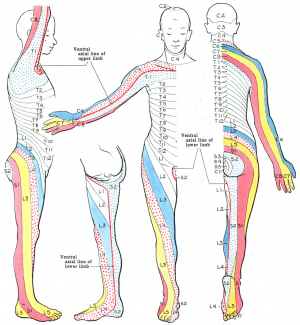

Patients with radicular pain will have pain following the dermatomal distribution, for example pain will radiate to:

- Medial forearm (T1)

- The axilla (T2)

- Nipple area (T4)

- Umbilicus (T10)

- Just above the inguinal ligaments (T12)

In upper thoracic and lateral disc herniations, radicular pain is more common and often reported in combination with some amount of axial pain. Second most commonly reported are sensory changes (e.g. parenthesias, dysesthesia) below the level of the lesion. Other symptoms include bladder and bowel dysfunction (15-20% of patients), hyperreflexia and gait impairment.[1][2]

The presentation of myelopathic pain is worrisome. The patient might complain of muscle weakness; the most common lower-extremity manifestation of thoracic disc herniation. Signs of myelopathy that indicate thoracic cord compression are:

- Positive Babinsky sign

- Sustained clonus

- Widebased gait

- Spasticity

Herniation of a thoracic disc is an uncommon cause of chest wall pain, but it has been documented in athletes.[5] A band-like pain in thoracic dermatomes is usually a symptom of intercostal neuralgia.[1]

Differential Diagnosis[edit | edit source]

Because thoracic disc syndroms are relatively rare, symptoms in this area will more likely arouse suspicion of disease of the internal organs or a primary disorder of the nervous system. It is important that the patient is examined thoroughly to rule out all other causes for symptoms.[1][2][6]

Rule out conditions that can cause thoracic pain such as:

- Diabetes and shingles

- Other mechanical issues such as oblique muscle pain, rib fracture, fracture of the facet joints and clavicle

- Malignancies, like neurofibroma

- Herpes zoster (can cause segmentally radiating pain with postherpetic neuralgia)

- Costotransverse joint syndrome due to inflammatory changes or arthrosis

- Infections, tumors and dilated arteries of the chest wall

- Referred pain from the organs (zones of Head)

- Tietze syndrome

- Scheuermann kyphosis

Pain referred around the chest wall tends to be costovertebral in origin.[7]

Diagnostic Procedures[edit | edit source]

Physical examination[edit | edit source]

The precise location of the pain and its radiation has to be explored. The character of the pain and provoking conditions (static and dynamic load) can provide information about the aetiology and nature of the pain (neuropathic versus nociceptive).

Physical examination should include assessment of sensation with pinprick and touch in the upper extremity, thorax, and abdomen in the dermatomal regions mentioned above to check for radiculopathy and also in the lower extremity to check for myelopathy. Also, for the lower extremity, proprioception and reflexes and tonus should be evaluated. Start your examination with:

- History

- Observation (standing) Examination

- Active movements (standing or sitting) - Forward flexion - Extension - Side flexion (left and right) - Rotation (left and right) - Combined movements (if necessary) - Repetitive movements (if necessary) - Sustained postures (if necessary)

- Passive movements (sitting) - Forward flexion - Extension - Side flexion (left and right) - Rotation (left and right) - Resisted isometric movements (sitting) - Forward flexion - Extension - Side flexion (left and right) - Rotation (left and right)

- Functional assessment

- Special tests (sitting) - Adson’s test - Costoclavicular maneuver - Hyperabduction (EAST) test - Roos test - Slump test

- Reflexes and cutaneous distribution (sitting) - Reflex testing - Sensation scan

- Special tests (prone lying) - Joint play movements (prone lying) - Posteroanterior central vertebral pressure (PACVP) - Posteroanterior unilateral vertebral pressure (PAUVP) - Transverse vertebral pressure (TVP) - Rib springing - Palpation (prone lying)

- Special tests (supine lying) - First rib mobility - Rib springing - Upper limb neurodynamic (tension) test 4 (ULNT4) - Palpation (supine lying) - Federung test (segmental translation of the thoracic vertebrea)

- Sensitivity of the thorax and stomach

After any assessment, the patient should be warned of the possibility of exacerbation of symptoms as a result of assessment.[7]

You can also take a look at Thoracic Examination on Physiopedia.

Additional diagnostics[edit | edit source]

There is a limited correlation between radiographical findings and clinical symptoms in non-specific thoracic spine pain.

MRI is the imaging method most used to arrive at a diagnosis[8]. However, it should be noted that there is a potential for spinal incidental findings. Studies that investigated the rate of abnormal findings in the asymptomatic patient suggest that although MRI is highly sensitive, it is not a specific imaging modality. MRI is superior to CT to demonstrate degenerative changes, disc protrusion and nerve root compression. In addition, intra- and extradural tumours can easily be seen on MRI.[9]

Additional imaging is indicated in the case of:

- Trauma (with or without osteoporosis)

- Suspicion of malignancy, particularly in patients with a history of malignancy and acute thoracic pain

- In case of neurological deficits

- Suspicion of pathology in the chest wall and/ or presence of pulmonary complaints

- Suspicion or presence of visceral pathology

Psycho-cognitive diagnostics[edit | edit source]

- Quality of life questionnaire

- VAS-pain scale

- Pain Catastrophizing Scale

- Fear-avoidance Beliefs Questionnaire

- Functional Rating Index

- Patient Specific Functional Scale

- Tampa Scale for kinesiophobia

Outcome measures[edit | edit source]

Passive movements of the thoracic spine and normal end feel:[7]

• Forward flexion (tissue stretch)

• Extension (tissue stretch)

• Side flexion, left and right (tissue stretch)

• Rotation, left and right (tissue stretch)

Loss of sensitivity indicates whether or not the pain is neuropathic. Pain provocation by performing passive movements, in particular rotation, forward flexion, backward flexion and lateral flexion can indicate a spinal aetiology.

Weakness, inflexibility and/or myofascial pain in the thoracic spine as well as the abdominal and hip musculature can be related to thoracic discogenic syndrome.[6] In the case of purely discogenic pain or thoracic radiculopathy, the upper extremity reflexes as well as the patellar and Achilles reflexes should be normal. If there is weakness associated with hyperactive patellar or achilles reflexes or spasticity, myelopathy is indicated. [10]

Paralysis of the lower abdominal muscles while the upper abdominal muscles preserve their strength can be a sign of leasion at T9/T10. The lesion can cause a Beevor sign, where the umbilicus makes an upward movement when the abdominal wall contracts. Observing if the movement of the rectus abdominis is asymmetric.

Sensory symptoms can be present if the patient has a thoracic disc herniation. It can cause altered sensation to light touch or pinprick along a dermatomal pattern. Cord compression and myelopathy should be strongly considered if a sensory level is established such that sensation is consistently altered below a specific dermatome.

Provocative manoeuvres such as the Spurling manoeuvre (cervical radiculopathy) and the Straight-Leg Raise test or the Slump Test (lumbosacral radiculopathy) may exclude a thoracic disc syndrome.[1][10][8]

Thoracic intervertebral disc degeneration on MRI is shown by a decrease in signal intensity with or without loss of disc height. A normal, healthy disc displays a high intensity signal. Disc degeneration can be detected by a reduced signal intensity due to loss of water from the nucleus pulposus. [1]

Medical Management[edit | edit source]

Most patients with symptomatic thoracic disc disease will respond favourably to non-operative management. Conservative medical treatment includes rest (in the case of an acute problem), anti-inflammatory drugs and physical therapy.

It is more likely for patients with radicular pain to take drugs than those with axial pain only. Most often prescribed are NSAIDs, skeletal muscle relaxants, opioid analgesics, benzodiazepines, systemic corticosteroids, antidepressants and anticonvulsants. Pharmacotherapy is considered as part of treatment in the initial stages and has not been proven effective as a stand-alone treatment except in acute episodes of radicular pain.[6][11]

For patients with symptomatic thoracic disc herniations who are unresponsive to conservative treatment, surgery is indicated. During surgery, the ossified disc that decompresses the region will be removed - relieving pressure on the nerve or spinal cord. Even though thoracic disc herniation surgery has advanced over the years, the complication rate is still 20-30%. Part of this high rate is the proximity of the spinal cord.[1][6][12][13]

Recent research is focussing on the regeneration of the intervertebral disc using biotherapy such as molecular and cell therapies, nucleic acid-based therapies, and mechanoregulated cell-based therapies. At this stage, the clinical uses of these biotherapies are short-term effective and offer insufficient stability. Regeneration of the degenerative disc is highly complex because of its natural composition, microstructure and mechanical properties.[14]

Physical Therapy Management[edit | edit source]

Several guidelines recommend physical exercise to alleviate pain. The goal of physiotherapy should be to increase the range of motion and pain relief, using a multiple-exercise based approach to strengthen supporting muscles and postural support.[15][11] Animal model studies show that physical exercise helps in intravertebral disk proliferation, particularly in moderate to high volume low repetition and frequency exercises.[16][17] Most patients (80%) with a prolapsed intervertebral disc respond in 4-6 weeks to conservative therapy.[18][19]

Mechanical strain on the disc can be reduced by horizontal positioning, although bedrest is usually not indicated. The application of heat can bring relief by relaxing the reflexive tension of the thoracic musculature, particularly the paravertebral extensors of the trunk and by promoting circulation.[1]

Some ideas from Physiopedia for physical therapy treatment:

- Exercise in pain management

- Top 3 thoracic spine mobility exercises (Physiospot)

- Thoracic Manual Techniques and Exercises

Case Studies[edit | edit source]

- Unusual chest wall pain caused by thoracic disc herniation in a professional baseball pitcher

- Histologically proven acute paediatric thoracic disc herniation causing paraparesis

- Acute chest pain in a top soccer player due to thoracic disc herniation

Clinical Bottom Line[edit | edit source]

The term ‘thoracic syndrome’ refers to all pathological clinical manifestations due to functional (physiopathological) disturbances and degenerative changes of the thoracic motion segments.[1] Due to the rarity of this subject, little importance is attached to it in the literature.[9] Articles suggest an incidence between 0.2% and 5.0% of all intervertebral disc herniations with more presentations in males. [20]

Most of the disc disorders are asymptomatic If, nevertheless, symptoms are extant, pain is the most common. Other symptoms may include sensory disturbances, referred pain, weakness in the abdominal and intercostal muscles, paresthesias, weakness of the lower extremities and bladder symptoms.[1][9][10][8][20]

One of the main problems in the treatment of thoracic disc herniation has been the lack of accuracy of diagnostic tests, leaving it to be a diagnosis when other things have been ruled out. Thoracic disc herniation can be revealed by MRI but the relation between symptoms and imaging is low. Musculoskeletal, reflexes, sensory aspects, strength and provocative manoeuvres should be tested.[10][8][1]

Physical therapy should be focussed on increasing the range of motion and pain relief, using a multiple-exercise based approach to strengthen muscles and postural support.[15][11]

References[edit | edit source]

- ↑ 1.00 1.01 1.02 1.03 1.04 1.05 1.06 1.07 1.08 1.09 1.10 1.11 1.12 1.13 1.14 Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; no text was provided for refs namedp1 - ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 2.4 Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; no text was provided for refs named:0 - ↑ Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; no text was provided for refs named:1 - ↑ Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; no text was provided for refs named:2 - ↑ 5.0 5.1 Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; no text was provided for refs named:3 - ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 6.3 6.4 Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; no text was provided for refs named:5 - ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; no text was provided for refs named:4 - ↑ 8.0 8.1 8.2 8.3 Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; no text was provided for refs namedp0 - ↑ 9.0 9.1 9.2 Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; no text was provided for refs namedp5 - ↑ 10.0 10.1 10.2 10.3 Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; no text was provided for refs namedp9 - ↑ 11.0 11.1 11.2 Manchikanti, Laxmaiah, and Joshua A. Hirsch. "Clinical management of radicular pain." Expert review of neurotherapeutics 15.6 (2015): 681-693.

- ↑ Ruetten S, Hahn P, Oezdemir S, Baraliakos X, Godolias G, Komp M. Operation of Soft or Calcified Thoracic Disc Herniations in the Full-Endoscopic Uniportal Extraforaminal Technique. Pain Physician. 2018 Jul;21(4):E331-E340.

- ↑ Kang J, Chang Z, Huang W, Yu X. The posterior approach operation to treat thoracolumbar disc herniation: A minimal 2-year follow-up study. Medicine (Baltimore). 2018 Apr;97(16):e0458.

- ↑ Amelot, Aymeric, and Christian Mazel. "The intervertebral disc: physiology and pathology of a brittle joint." World neurosurgery 120 (2018): 265-273.

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; no text was provided for refs named:6 - ↑ Luan S., Wan Q., Luo H., Li X., Ke S., Lin C., Wu Y., Wu S., Ma C. Running exercise alleviates pain and promotes cell proliferation in a rat model of intervertebral disc degeneration. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2015;16:2130–2144

- ↑ Steele J., Bruce-Low S., Smith D., Osborne N., Thorkeldsen A. Can specific loading through exercise impart healing or regeneration of the intervertebral disc? Spine J. Off. J. N. Am. Spine Soc. 2015;15:2117–2121

- ↑ Hofstee, Derk J., et al. "Westeinde sciatica trial: randomized controlled study of bed rest and physiotherapy for acute sciatica." Journal of Neurosurgery: Spine 96.1 (2002): 45-49.

- ↑ Weber, Henrik, Ingar Holme, and Even Amlie. "The natural course of acute sciatica with nerve root symptoms in a double-blind placebo-controlled trial evaluating the effect of piroxicam." Spine 18.11 (1993): 1433-1438.

- ↑ 20.0 20.1 Jed S. Vanichkachorn, MD and Alexander R. Vaccaro, MD. Thoracic Disk Disease: Diagnosis and Treatment. The American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons. 2000. 8:159-169.