Osteogenesis Imperfecta: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

No edit summary |

||

| Line 52: | Line 52: | ||

#* translucent and weakened teeth | #* translucent and weakened teeth | ||

#* can affect baby and adult teeth<ref>Dentiogenesis Imperfecta. Available from: https://medlineplus.gov/genetics/condition/dentinogenesis-imperfecta/ (Accessed, 15/10/2021).</ref> | #* can affect baby and adult teeth<ref>Dentiogenesis Imperfecta. Available from: https://medlineplus.gov/genetics/condition/dentinogenesis-imperfecta/ (Accessed, 15/10/2021).</ref> | ||

# | # Hearing impairments | ||

OI can also cause laxity of ligamentous, joint [[Hypermobility Syndrome|hypermobility]], short stature and individuals are prone to bruising.<ref name=":0" /> | OI can also cause laxity of ligamentous, joint [[Hypermobility Syndrome|hypermobility]], short stature and individuals are prone to bruising.<ref name=":0" /> | ||

Revision as of 05:58, 24 April 2023

Genetic_DisordersOriginal Editors - Barrett Mattingly from Bellarmine University's Pathophysiology of Complex Patient Problems project.

Top Contributors - Barrett Mattingly, Lucinda hampton, Jess Bell, Admin, Uchechukwu Chukwuemeka, Robin Tacchetti, Kim Jackson, Kirenga Bamurange Liliane, Dave Pariser, WikiSysop, Meaghan Rieke, Anna Fuhrmann, 127.0.0.1, Heidi Johnson Eigsti, Elaine Lonnemann and Wendy Walker

Introduction[edit | edit source]

Osteogenesis imperfecta (OI) is a "heterogeneous group of congenital, non-sex-linked, genetic disorders".[1] It affects the production or processing of type 1 collagen, and therefore, impacts connective tissue and bone.[1][2]

It is also referred to as "brittle bone disease". Individuals with OI are susceptible to fractures and reduced bone density.[2] They may present with osteoporosis and blue sclera (i.e. the white part of the eye), and their teeth and hearing can be affected.[1] It can also impact mobility and an individual's ability to perform activities of daily living.

OI can have a negative effect on the social and emotional well-being of young people with this condition and their families. Adopting a coordinated, multidisciplinary team approach helps to ensure that children with OI can "fulfill their potential, maximizing function, independence, and well-being."[3]

Epidemiology[edit | edit source]

OI is a rare condition. The estimated incidence is approximately 1 in every 15,000 to 20,000 births.[2] It affects males and females equally, and there are no differences in terms of race / ethnic group.[1]

Aetiology[edit | edit source]

OI usually occurs secondary to mutations in the COL1A1 and COL1A2 genes, but there have been diverse mutations related to OI identified more recently.[2]

Pathology[edit | edit source]

In OI, the synthesis of type I collagen is affected. Type I collagen forms the main protein of the extracellular matrix of many of our tissues, including our skin, bones, tendons, skin and sclerae.[1][2]

Types of OI[edit | edit source]

There are at least eight different types of OI, but three types are said to be easily distinguished.[1]

- Type I:[4]

- The most common and mildest type of OI

- Around 50% of children with OI have Type 1 OI

- Individuals have few fractures / deformities

- Type II:[4][2]

- The most severe type of OI - it is a lethal condition, usually within weeks of birth

- Causes severe disruption of the "qualitative function" of the collagen molecule[2]

- Infants with Type II OI present with very short arms and legs, small chest and they have delayed ossification of the skull

- There may be fractures at birth, low birth weight and under-developed lungs

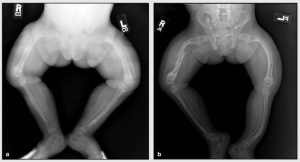

- Type III:[4]

- Children who have severe clinical signs tend to have Type III OI

- They tend to present with moderate to severe fragility of bones, coxa vera, they may have slightly shorter arms and legs, and have arm, leg, and rib fractures

- Infants may have a larger head, a triangular-shaped face, changes in their chest and spine (scoliosis), and difficulties with breathing and swallowing

- May also have frontal bossing (i.e. prominent forehead), basilar invagination, short stature

- Symptoms vary in each infant[4]

- Types IV to VIII are not common and vary in terms of their severity.[1]

Clinical presentation[edit | edit source]

There are four major clinical features that characterise OI.[1][4]

- Osteoporosis / bone fragility

- fractures

- bone deformities

- Discoloration of the sclera (white of the eye)

- may be blue or gray in colour

- Dentinogenesis imperfecta

- discolouration of teeth (e.g. blue-gray / yellow-brown colour)

- translucent and weakened teeth

- can affect baby and adult teeth[5]

- Hearing impairments

OI can also cause laxity of ligamentous, joint hypermobility, short stature and individuals are prone to bruising.[1]

Diagnosis[edit | edit source]

The following diagnostic tests may be recommended:[4]

- X-rays: able to show weakened / deformed bones, fractures

- Lab tests: including blood, saliva, skin and gene testing

- Dual Energy X-ray Absorptiometry scan (DXA or DEXA scan): to investigate softening of bone

- Bone biopsy (taken at the hip)

Treatment[edit | edit source]

Treatment focuses on the prevention of deformities and fractures and the maintenance of independence.[4]

Management options include:[1]

- Surgery to help prevent fractures and to correct deformities

- Intramedullary rods with osteotomy for severe bowing of the long bones

- Intramedullary rods for children with frequent fractures of long bones

- Different types of rods (surgical nails) are available to address issues related to surgery, bone size, and the prospect for growth; the two major categories of rods are telescopic and non-telescopic.

- Care of fractures. The lightest possible materials are used to cast fractured bones. To prevent further problems, it is recommended that a child begin moving or using the affected area as soon as possible.

- Bisphosphonates

- Growth hormone therapy[1]

- Dental procedures: Treatments including capping teeth, braces, and surgery may be needed.

- Physical and occupational therapy are both very important in babies and children with OI.

- Assistive devices. Wheelchairs and other custom-made equipment may be needed as babies get older.[4]

Prognosis[edit | edit source]

Prognosis is variable depending on the type of OI.[2]

- Age of onset of long bone fractures is a prognostic indicator for ambulatory ability.

- Survival: Location and severity of fractures, and appearance of the skeleton on radiography are significant indicators for survival.

- The type of OI is the most important clinical indicator for ability to ambulate. Early achievement of motor milestones is associated with the ability to walk independently when the type of OI is not known.[6]

Complications[edit | edit source]

Complications associated with OI vary depending on the type of OI, but they can affect most body systems. They may include the following:[2][4]

- Respiratory infections eg. COVID 19, pneumonia

- Cardiac issues eg. cardiac valve defects

- Kidney stones

- Tumour (osteogenic sarcoma)

- Joint conditions

- Basilar invagination

- Eye conditions and vision loss

- Malignant hyperthermia

Team Approach[edit | edit source]

OI should be managed with an interdisciplinary team that may include primary care physician, orthopedist, geneticist, nutritionist, social worker, and psychologist, physiotherapists, occupational therapists. Pulmonologists may be involved in the care of individuals who have scoliosis that impacts pulmonary function.[7]

Rehabilitation[edit | edit source]

Therapists should remember the following when working with individuals with OI and their families:[7]

- Listen and respect individuals with OI and their families.

- Set goals that are realistic, achievable, and incremental.

- Weakness affects movements in OI - individuals with OI do not tend to have other neurological issues such as impaired coordination, sensation or cognition.

- Individuals with OI may be fearful of fractures and this can significantly impact movement. It can be useful to:

- establish safe movement patterns

- encourage self-confidence

- optimise strength

- Expect success - with the appropriate environment and equipment, most individuals with OI can perform most activities of daily living, including self-care, school and work.

Enhancing strength and function is essential for health and wellbeing and bone health. Rehabilitation approaches include:[7]

- Exercise, including weight bearing activities (braces may be needed)

- Low-impact activities such as swimming (precautions must be defined)

- Care with safe handling and encouraging changes in body positions / postures throughout the day to help strengthen muscles / prevent deformities

- Prescribing appropriate adaptive equipment (e.g. cane, walker, manual or power wheelchair).

- Adapting the environment as needed (e.g. at work, home, school)

Individuals with OI might require intermittent or long-term rehabilitation for the following reasons:

- They have delays or weakness in motor skills

- They have had a fracture, surgery or injury

- They are experiencing fear of movement and are trying new skills and activities

- They are transitioning to a new stage of life etc, and need to get used to a new environment or train for a specific activity of daily living[7]

Key Principles of Therapeutic Strategies

When designing a rehabilitation programme for OI, it is necessary to engage in an appropriate task analysis. The following are useful points to consider:[7]

- Skill progression - develop and progress gross motor skills (reaching, sitting etc) if they are delayed / difficult, particularly for individuals with severe OI. Skills may need to be retrained in adults after injury.

- Using preventive positioning, protective handling and active movement with gradual progression can help to facilitate motor skill development safely.

- Hydrotherapy can be useful for motor skill development and for individuals with fear of movement.

- It is vital to ensure that an individual has appropriate equipment and assistive devices.

- Encourage healthy living to promote general health.

Children of Glass[edit | edit source]

The following videos include excerpts from the Discovery Health documentary on the genetic brittle bone disorder "Osteogenesis Imperfecta" .

Resources[edit | edit source]

References[edit | edit source]

- ↑ 1.00 1.01 1.02 1.03 1.04 1.05 1.06 1.07 1.08 1.09 1.10 Osteogenesisi Imperfecta. Available from: https://radiopaedia.org/articles/osteogenesis-imperfecta-1 (Accessed, 15/10/ 2021).

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 2.4 2.5 2.6 2.7 2.8 Subramanian S. StatPearls Publishing LLC.; Treasure Island, FL, USA: 2021. Osteogenesis Imperfecta.

- ↑ Marr C, Seasman A, Bishop N. Managing the patient with osteogenesis imperfecta: a multidisciplinary approach. Journal of multidisciplinary healthcare. 2017; 10:145.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 4.4 4.5 4.6 4.7 4.8 Osteogenesis Imperfecta. Available from: https://www.hopkinsmedicine.org/health/conditions-and-diseases/osteogenesis-imperfecta (Accessed, 15/10/2021).

- ↑ Dentiogenesis Imperfecta. Available from: https://medlineplus.gov/genetics/condition/dentinogenesis-imperfecta/ (Accessed, 15/10/2021).

- ↑ Engelbert RH, Uiterwaal CS, Gulmans VA, Pruijs H, Helders PJ. Osteogenesis imperfecta in childhood: prognosis for walking. J Pediatr. 2000 Sep;137(3):397-402.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 7.3 7.4 OI foundation Physical and Occupational Therapists Guide to Treating Osteogenesis Imperfecta Available:https://oif.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/08/PT_guide_final.pdf (accessed 15.10.2021)

- ↑ Bublitz Videos. Children of Glass - (Part 1 of 4). Available from: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=TpAMTOud3bw [last accessed 27/8/2020]

- ↑ Bublitz Videos. Children of Glass - (Part 2 of 4). Available from: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=GTpSxlPzC8k [last accessed 37/8/2020]

- ↑ Bublitz Videos. Children of Glass - (Part 3 of 4). Available from: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=L2f8fz6vzoI [last accessed 27/8/2020]

- ↑ Bublitz Videos. Children of Glass - (Part 4 of 4). Available from: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=QvbY7XqyMz8 [last accessed 27/8/2020]